Among the special events of Pekin’s Bicentennial last year was the first-ever German Frühlingfest (Springfest) in Pekin, held at the Avanti’s Event Center on April 14 and co-sponsored by Harmonie-Concordia, an affiliate of the Peoria German-American Society. The event celebrated German culture and Pekin’s rich German heritage, which extends almost back to the very founding of Pekin in 1830.

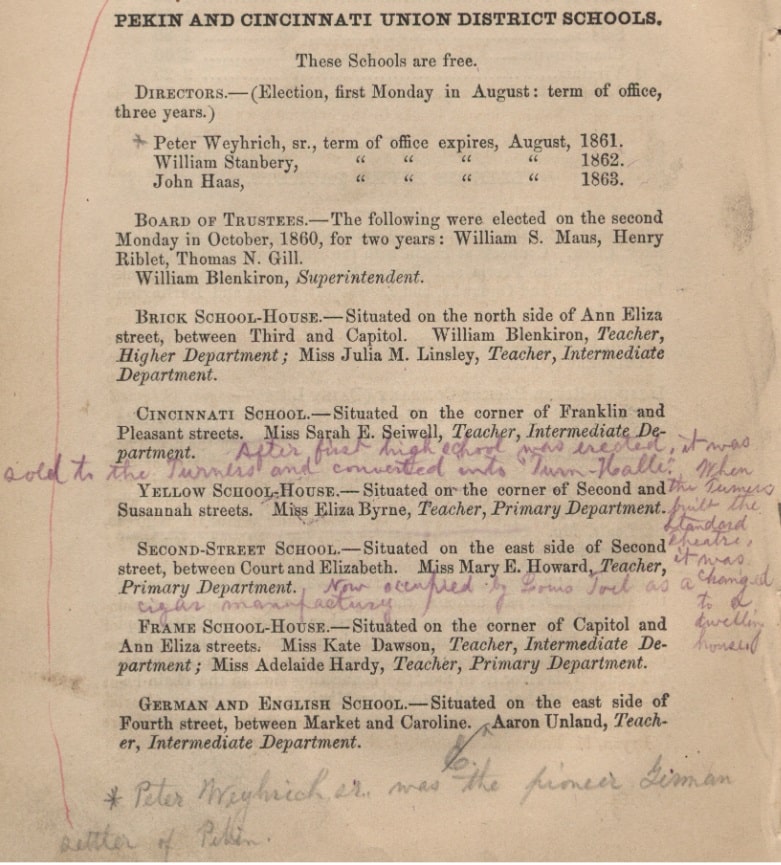

On page 70 of the copy of the 1861 Pekin city directory that was owned by Pekin’s pioneer historian William H. Bates is a handwritten note that says, “Peter Weyhrich, sr., was the pioneer German settler of Pekin.” Weyhrich (1806-1879), an immigrant from Hesse-Darmstadt who came to Pekin in 1831 or 1832, was one of our early businessmen and community leaders, taking part in the formation of Pekin’s first railroad companies. He served on Pekin’s school board in the 1860s and was Pekin’s mayor in 1858 and 1859 – the first of our mayors to be of German ethnicity.

Weyhrich was a kind of advance scout for the large host of German immigrants who would soon come to Pekin seeking freedom and better opportunities than were afforded them in the Old Country. From 1850 to the 1890s, more than 4 million Germans arrived in the U.S. In 1860, German immigrants were 8% of Illinois’ population. The 1880 census counted about 172,000 German-born Illinois residents, most of them from Prussia, though there were also many from Bavaria, Hessia, and other German lands.

19th-century German immigration to the U.S. was spurred by political, religious, and economic upheaval. Immigrants sought to escape the wars that afflicted the German states, or objected to their state’s meddling in religious matters, or were displaced by industrialization and urbanization.

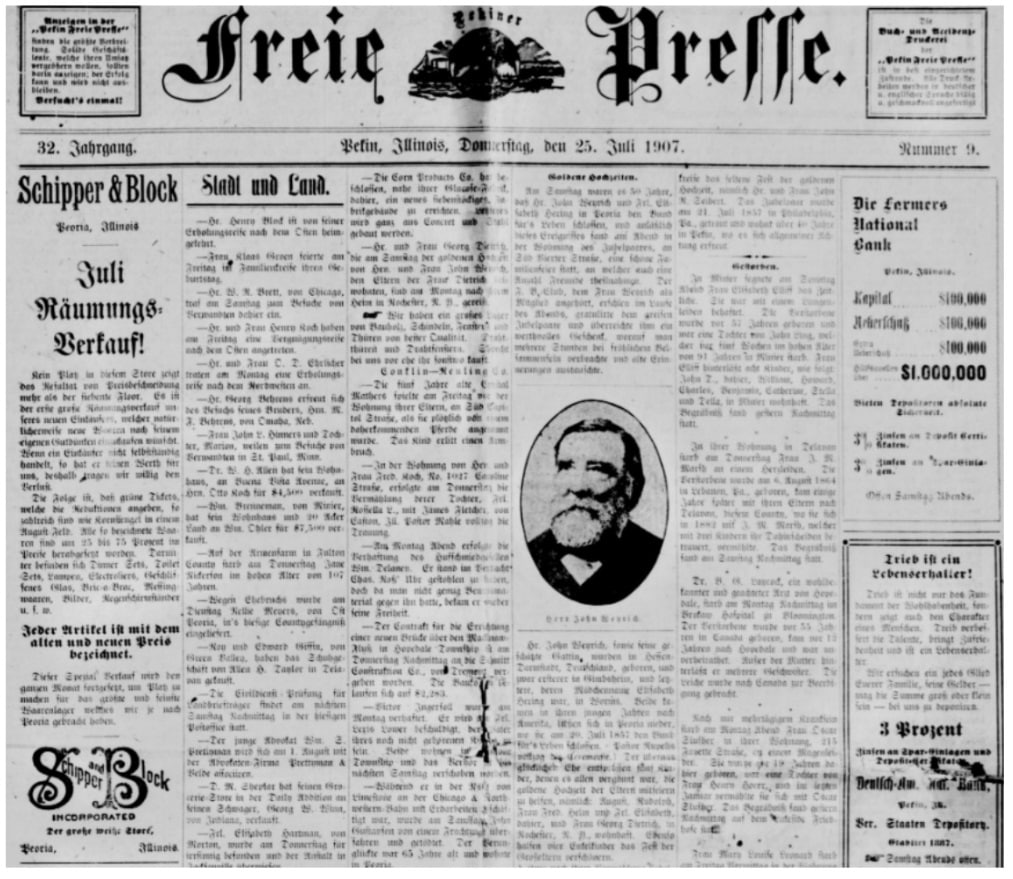

In the period from 1850 to 1870 the number of German settlers in Pekin rapidly increased until German families made up the majority of our city’s population. At one time a visitor to Pekin would have been at least as likely (if not more likely) to hear German spoken here as English. There also was a well-read German-language newspaper, called Die Pekiner Freie Presse (“Pekin Free Press”), and many businesses had signs in their windows telling people that German was spoken there.

The transformation of Pekin into a German town can be tracked in old city directories. Even in 1861, the first city directory is filled with German names, and by the time of the next directory in 1871 the German names were even more numerous. In 1890s city directories it is far easier to find a German name than a non-German name. Many of these names became prominent in Pekin’s history, for they belonged to the people who truly built this city, ran its governmental bodies and businesses, worshipped in its churches, and gathered for recreation in the city’s parks, theaters, and social clubs. Along with Weyhrich, they included surnames such as Westerman, Ehrlicher, Herget, Velde, Luppen, Smith, Hippen, Hinners, Albertsen, Voth, Duisdieker, Birkenbusch, Kriegsman, Koch, Schipper, Block, Reuling, Taubert, Zerwekh, Zuckweiler, Jaeckel, Ehrhardt, Steinmetz, Nedderman, Schaefer, Schenk, Moenkemoeller, Unland, Lautz, Dirksen, Gehrig, and a great many others.

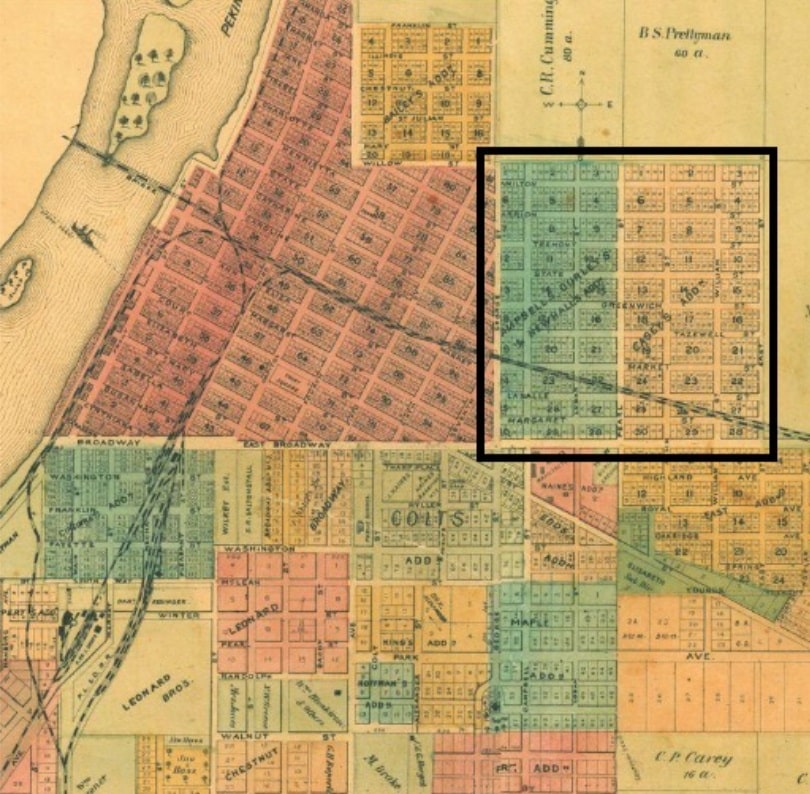

When Pekin’s German immigrants began to arrive, they could be found living in almost any part of the city. However, a great number of them made their homes in the old northeast quarter of Pekin, bounded on the south by Broadway and on the north by Willow, with George Street, today called Eighth Street, as its western boundary. (In those days, the neighborhoods north of Willow and east of 14th Street did not yet exist.) This became Pekin’s old German Quarter, and was given the German nickname Bohnen Viertel – literally, the “beans quarter” – “Bean Town” in English. The name refers to the gardens that the German immigrants grew to supply food for their families or for sale at local grocery stores. It was in that quarter, at 1100 Hamilton St., where the immigrant parents of U.S. Senator Everett M. Dirksen lived, and where Dirksen and his twin brother Thomas lived as children. The name Bohnen Viertel or Bean Town has long since fallen into disuse. The only visible trace of that place-name today is in the name of the Bean Town Antiques building, a former market at the corner of 14th and Catherine streets.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the varied spiritual needs of Pekin’s German population were served by Sacred Heart Catholic Church (which burned down in 1930 and was subsequently merged with St. Joseph’s Catholic Church), the German Methodist Episcopal Church (today’s Grace United Methodist), St. Paul’s German Evangelical Church (today’s St. Paul United Church of Christ), a second German Evangelical Church (long defunct), St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church (which still exists today along with its daughter church, Trinity Evangelical Lutheran), and the Second Dutch Reformed Church (known as “the Dirksen church” since the Dirksens were members; this church dissolved in 2019).

Pekin’s German Christian denominations generally match those found in the Old Country. While the majority of Germans were either Lutheran or Catholic, great numbers also were Reformed (Calvinist). The Prussian king’s attempt to force the union of his Lutheran and Reformed subjects spurred a large wave of immigrants to America to escape the king’s meddling.

Because the Reformed denomination was most prominent in the Netherlands and neighboring Ostfriesland on the North Sea coast, the denomination came to be called “Dutch” Reformed. Ostfrieslanders settled across Central Illinois in very large numbers, especially here in Pekin. The Dirksens are merely the best known of Pekin’s old Ostfrieslander families.

Many other German-Americans in Tazewell County have belonged to Anabaptist traditions, such the Mennonites or the Apostolic Christians. Those denominations have never had congregations within the Pekin city limits, though Bethel Mennonite Church (which dissolved in 2009) was just east of Pekin, while Midway Mennonite (which dissolved in 1989) was just to the south.

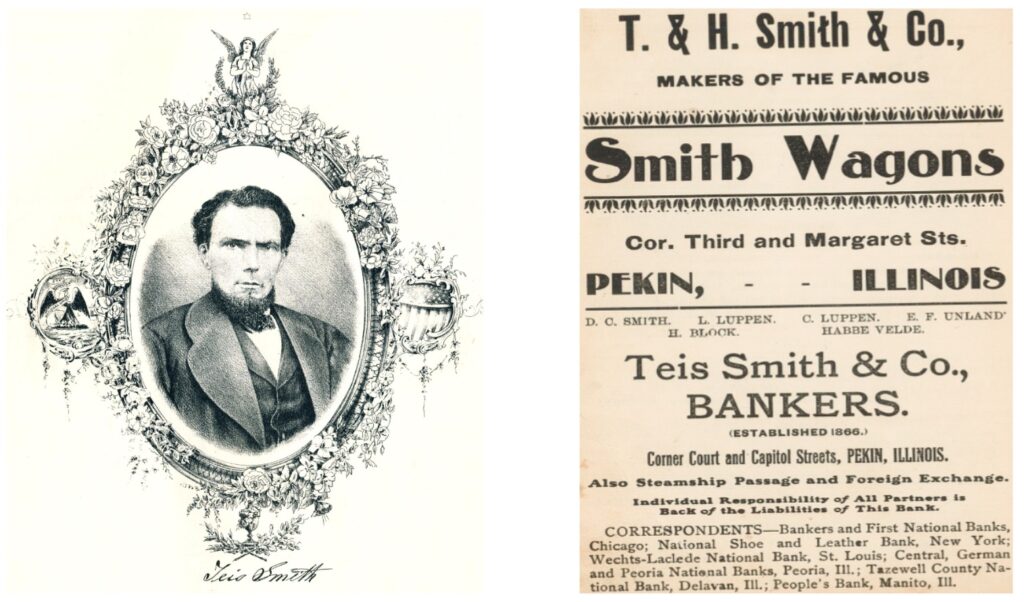

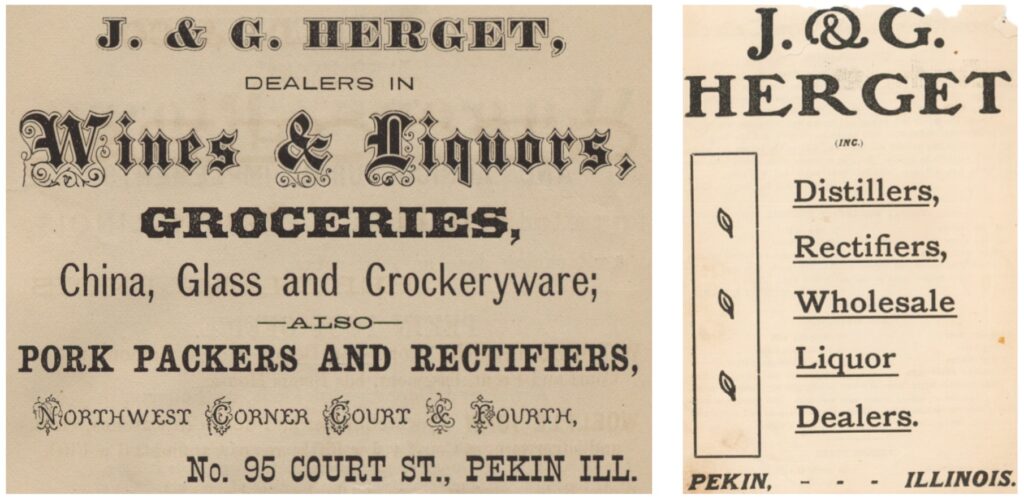

Pekin has had a vast number of the German-founded businesses, institutions, and community groups. Some of these included Pekin’s old distilleries – one of which was operated by Henry P. Westerman – that formerly were a major component of Pekin’s economy. Other significant businesses were the Teis Smith Wagon Co., the Hinners Organ Co., the Albertsen & Koch Furniture Store, and Birkenbusch Jewelers and Clocksmiths.

Pekin’s German immigrants also made a huge mark in Pekin’s financial dealings. Downtown Pekin once was home to the Teis Smith Bank (an institution that came to a sudden and scandalous end in 1906), and for the longest time was the home of the German-American National Bank (later American National Bank, then First National Bank & Trust Co. of Pekin, and finally AMCORE Bank), and Herget National Bank (later Busey Bank, which last year sold the former Herget downtown headquarters to the Tazewell County Resources Center).

The bank’s founders the Hergets are probably Pekin’s best remembered German family. Grand homes of prominent Herget family members still exist in the historic Washington St. and Park Ave. area of town, most notable the Carl Herget Mansion at 420 Washington St. John Herget (1830-1899), who served as Pekin mayor in the 1870s, and his younger brother George Herget (1833-1914) started out as partners in a dry goods store on Court Street. George later got into alcohol distilling and sugar refining, finally getting into banking as founder of Herget Bank. George Herget also served on the city council, county board, and school board, was also the first president of the Pekin Park District board. He and his wife Caroline also donated the land to provide a place where Pekin’s Carnegie Library could be built in 1903.

Pekin’s leading German families tended to intermarry with each other, and that is shown in the Herget family tree, which shows marital alliances with the Ehrlichers, Reulings, Veldes, Kraegers, Meisingers, Blocks, Conzelmans, and Steinmetzes, all prominent families of Pekin’s German period.

John Herget’s daughter Martha (Herget) Steinmetz (1868-1947) was also founding president of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) of Pekin. Martha’s father-in-law was the patriarch of the Steinmetz family, Peter Steinmetz Sr. (1839-1908), whose well-known business was P. Steinmetz & Sons Dry Goods, located in what is now the Hamm’s Furniture building. The Steinmetz store itself was successor at that site of Schilling & Bohn, the furniture and undertaking business of two other Germans, Conrad Schilling and Andrew Bohn.

Other notable German businessman of those days include Otto Koch, co-founder of the W. A. Boley Ice Co., and Philip M. Hoffman of the Pekin Hardware Co. (who was succeeded in the business by his son Ernest).

Pekin’s Germans also left their mark in local arts and entertainment, as is seen in the old Maennerchor (“men’s choir”) Hall upstairs in the Arlington, Gehrig’s 7th Regiment Band, and the Turner Opera House built at Capitol and Elizabeth in 1890, which later became The Standard and The Capitol Theatre before it was replaced in 1928 by Anna B. Fluegel’s Chinese-themed Pekin Theater.

Over the course of five decades of flourishing German culture in Pekin, the children of the immigrants gradually assimilated into the nation’s English-speaking American culture. Pekin’s German Methodist Episcopal Church dropped the “German” from it name a few years before World War I.

Assimilation ramped up with the U.S. entry into World War I in 1917 on the side of the Allies and against the German/Austrian-led Central Powers. The war against Germany brought an American reaction against all things German.

The children of German immigrants went to added lengths to demonstrate their patriotism and loyalty. Pekin businesses took down their “German Spoken Here/Wir sprechen hier Deutsch” signs, the German-American National Bank dropped “German-,” our old German churches downplayed their origins, and, finally, Die Freie Presse switched to English, and subsequently closed down.

With the passing of the decades, though, old animosities have subsided, and Pekinites this year again gathered to celebrate the great contributions that our German forebears made to Pekin’s growth and progress.