This is a slightly revised version of one of our “From the Local History Room” columns that first appeared in May 2015 before the launch of this weblog, republished here as a part of our Illinois Bicentennial Series on early Illinois history.

Three years ago a book was published about a little known episode and an all-but-forgotten individual in Pekin’s history – an episode that helped confirm Illinois as a free state. The book was among the publications honored at the 2015 annual awards luncheon of the Illinois State Historical Society held April 25, 2015, at the Old State Capitol in Springfield.

Entitled “Nance: Trials of the First Slave Freed by Abraham Lincoln – A True Story of Nance Legins-Costley,” it was written by local historian Carl M. Adams and illustrated by Lani Johnson of Honolulu, Hawaii. Adams, formerly of Pekin, then resided in Germany (but now is in Maryland), and was unable to attend the awards banquet in Springfield, so he asked his friend Bill Maddox, a retired Pekin police office and former city councilman, to receive the award on his behalf. Maddox is one of Adams’ collaborators and over the years has helped Adams in organizing his research.

Adams has previously published two papers on the same subject: “The First Slave Freed by Abraham Lincoln: A Biographical Sketch of Nance Legins (Cox-Cromwell) Costley (circa 1813-1873),” which appeared in the Autumn 1999 issue of “For the People,” newsletter of the Abraham Lincoln Association; and, “Lincoln’s First Freed Slave: A Review of Bailey v. Cromwell, 1841,” which appeared in The Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, vol. 101, no. 3/4, Fall-Winter 2008. In contrast to those papers, however, Adams’ 87-page book “Nance” distills the fruit of his many years of historical research, presenting Nance’s story in the form of a biography suitable for a middle-school audience and ideal for a junior high or middle school classroom.

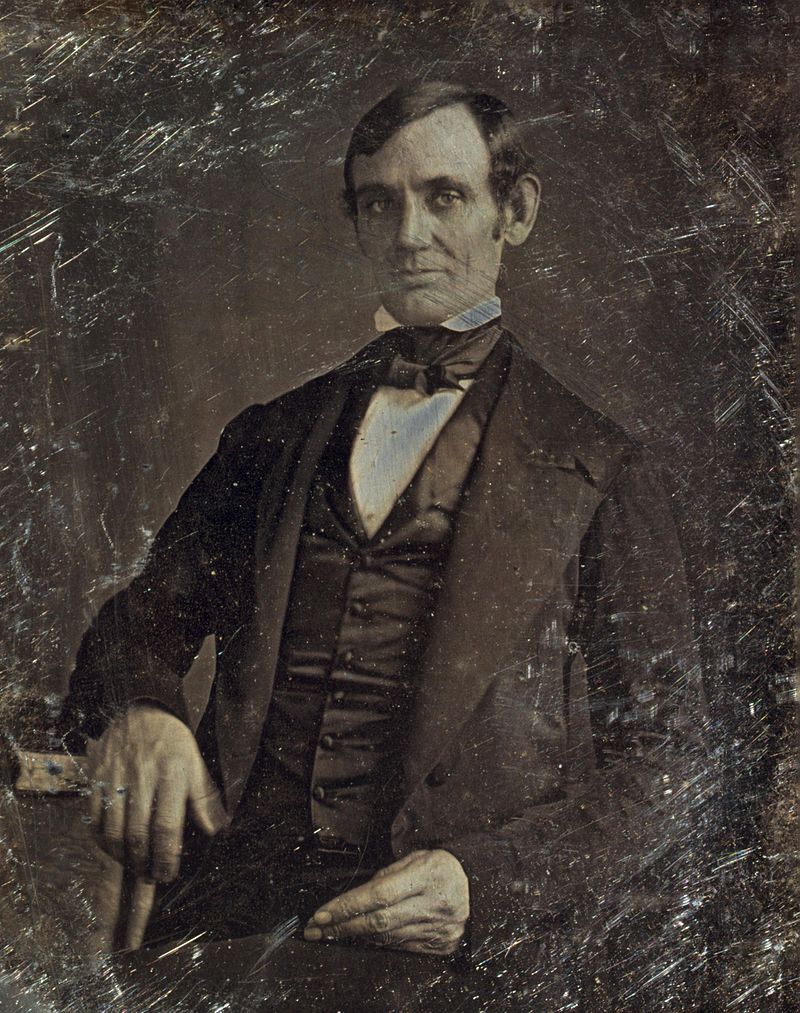

Though Nance’s story is little known today, during and after her own lifetime her struggles to secure her freedom were well known in Pekin, and Nance herself came to be a well regarded member of the community. As this column had previously discussed (Pekin Daily Times, Feb. 11, 2012), Nance obtained her freedom as a result of the Illinois Supreme Court case Bailey v. Cromwell, which Abraham Lincoln argued before Justice Sidney Breese on July 23, 1841. It was the culmination of Nance’s third attempt in Illinois courts to secure her liberty, and it resulted in a declaration that she was a free person because documentation had never been supplied proving her to have been a slave or to have agreed to a contract of indentured servitude. Breese’s ruling is also significant in Illinois history for definitively settling that Illinois was a free state where slavery was illegal.

Another significant aspect of this case is indicated in an 1881 quote from Congressman Isaac Arnold that Adams includes in his book. Arnold wrote, “This was probably the first time he [Lincoln] gave to these grave questions [on slavery] so full and elaborate an investigation . . . it is not improbable that the study of this case deepened and developed the antislavery convictions of his just and generous mind.”

Pekin’s pioneer historian William H. Bates was also opposed to slavery and deeply admired Lincoln. Bates also knew Nance Legins-Costley, and, five years after Lincoln’s assassination, Bates made sure to include her in his first published history of Pekin, the historical sketch that Bates wrote and included in the 1870-71 Sellers & Bates Pekin City Directory, page 10. There we find a paragraph with the heading, “A Relic of a Past Age”:

“With the arrival of Maj. Cromwell, the head of the company that afterwards purchased the land upon which Pekin is built, came a slave. That slave still lives in Pekin and is now known, as she has been known for nearly half a century, by the citizens of Pekin, as ‘Black Nancy.’ She came here a chattle (sic), with ‘no rights that a white man was bound to respect.’ For more than forty years she has been known here as a ‘negro’ upon whom there was no discount, and her presence and services have been indispensible (sic) on many a select occasion. But she has outlived the era of barbarism, and now, in her still vigorous old age, she sees her race disenthralled; the chains that bound them forever broken, their equality before the law everywhere recognized and her own children enjoying the elective franchise. A chapter in the history of a slave and in the progress of a nation.”

Remarkably, Bates doesn’t mention how Nance obtained her freedom, nor does he mention Lincoln’s role in her story. He doesn’t even tell us her surname. That’s because the details were then well-known to his readers. Later, her case would get a passing mention in the 1949 Pekin Centenary, while the 1974 Pekin Sesquicentennial would provide a more extended treatment of the case. But in none of the standard publications on Pekin history is personal information on Nance and her family included.

“What I did figure out,” Adams said in an email, “was that all the stories of Nance were positive up until the race riots in Chicago in 1918-1919 followed by a rebirth of the Klan in Illinois, and stories of Nance and her family disappeared, before the age of radio and TV.”

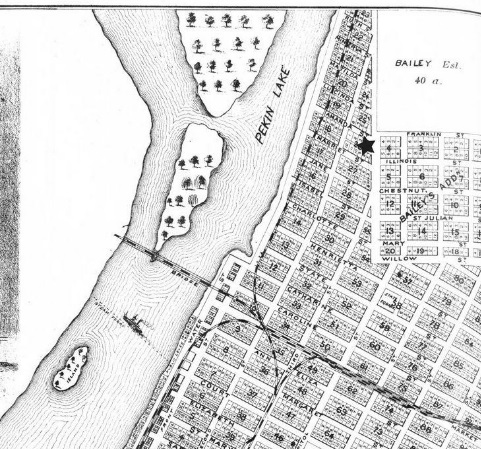

Since she had been forgotten and scant information was available in the standard reference works on Pekin’s history, Adams had to scan old census records, court files, coroner’s reports and newspaper articles to reconstruct the story of Nance’s life and the genealogy of her family. He learned that Nance was born about 1813, the daughter of African-American slaves named Randol and Anachy Legins, and that she married a free black named Benjamin Costley. Nance and Ben and their children appear in the U.S. Census for Pekin in 1850, 1860, 1870, and even 1880 (though the 1880 census entry is evidently fictitious). The 1870-71 Pekin City Directory shows Benjamin Costley residing at the southwest corner of Amanda and Somerset up in the northwest corner of Pekin. Perhaps not surprisingly, Ben and Nance’s log cabin was adjacent to the old Bailey Estate, the land of Nance’s last master, David Bailey, one of the principals of the 1841 case in which Nance won her freedom.

In his email, Adams explains the challenge of “writing about the first slave freed by Lincoln, when no one even knows her last name. OK. How does one do that? Genealogy. It is close to impossible to trace the genealogy of a slave. Now what? Trace the genealogy of the people who claimed to own her soul. It took six genealogies minimum to figure out where Nance was and when back to the time of her birth. I did what Woodward and Bernstein did with ‘All the President’s Men’ – follow the money and the paper trail that followed the money, that’s how.”

Telling of how he became interested in Nance’s story and how he eventually came to write his book, Adams said, “In 1994 my wife was diagnosed with cancer. I was unemployed, and in debt and depressed because of all this. To distract my self-pity, I took an interest in Nance and slavery – who could be worse off than they? I tried free-lance writing, but in Greater Peoria, I couldn’t make a living at it. So research on a totally new story about A. Lincoln had to be a part-time, part-time, part-time ‘hobby,’ as my wife called it. That is why it took so long: five years of research packed into a 15-year period.”

“Nance deserves her place in history because of what she did, not what the others did,” Adam said. “At the auction on July 12, 1827, she just said ‘No.’ By indentured servitude law, the indenture was supposed to ‘voluntarily’ agree to a contract to serve. When Nathan Cromwell asked if she would agree to serve him she just said ‘no,’ which led to a long list of consequences and further legal issues in court.

“What makes her historically important was when she managed to get to the Supreme Court twice. In my history fact-check only Dred Scott had managed to do that and he lost. Then I discovered with primary source material that Nance had actually made it to the Supreme Court three times. The third time was never published nor handed down as a court opinion when the judge found out she was a minor just before age 14. This was truly phenomenal, unprecedented and fantastic for that period of history.”

As Ida Tarbell said of Nance in 1902, “She had declared herself to be free.”

Adams’ book may be previewed and purchased on Amazon.com or through the website www.nancebook.com.