By Jared L. Olar

Local History Program Coordinator

The decade of the Sixties was a time of momentous changes in the United States, and the Civil Rights Movement was responsible for many of those changes. The movement’s most historic achievements included the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 that outlawed racial discrimination across the board, a major legislative victory won with the help of Pekin’s own Sen. Everett M. Dirksen and that will have its 60th anniversary this summer.

Besides Dirksen’s pivotal role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act, there is another notable Pekin connection to the 1960s Civil Rights Movement: two Pekin clergymen and one Marquette Heights clergyman were present in Selma, Alabama, for the third of the historic marches there in March 1965. Of those three ministers, one passed away in 2011. I was able to contact and speak to one of the two ministers still living.

Following hard on their 1964 victory, the Civil Rights Movement’s activists shepherded by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his colleagues then turned their attention to securing the voting rights of African-Americans. But their direct but non-violent challenge to laws in the South that had all but nullified the 15th Amendment for Southern African-Americans was met with fierce and increasingly violent resistance.

Southern racists had already resorted to violence and terror during the run-up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964’s passage, including the KKK’s bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on 15 Sept. 1963, that took the lives of four African-American girls and injured 20 of the church’s members.

On 18 Feb. 1965 came another instance of racist violence, when Alabama state troopers beat civil rights protestors at Marion, Ala., near Selma. In this incident, the troopers shot Jimmie Lee Jackson as he tried to protect his mother from the troopers’ blows. Jackson died eight days later.

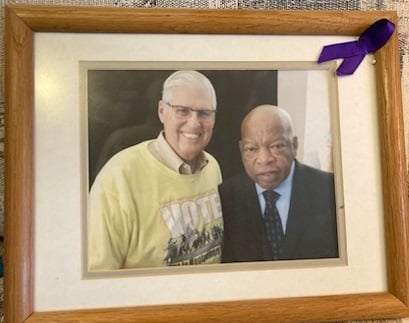

In response, Dr. King organized a march from Selma to the Alabama capital at Montgomery on Sunday, 7 March 1965. But state troopers violently disrupted the march, from which that day has been known ever since as Bloody Sunday. Victims of the troopers’ violence included Amelia Boynton, who was beaten unconscious, and John Lewis (1940-2020), who was beaten and his skull fractured. Photographs and news footage of this incident shocked the nation.

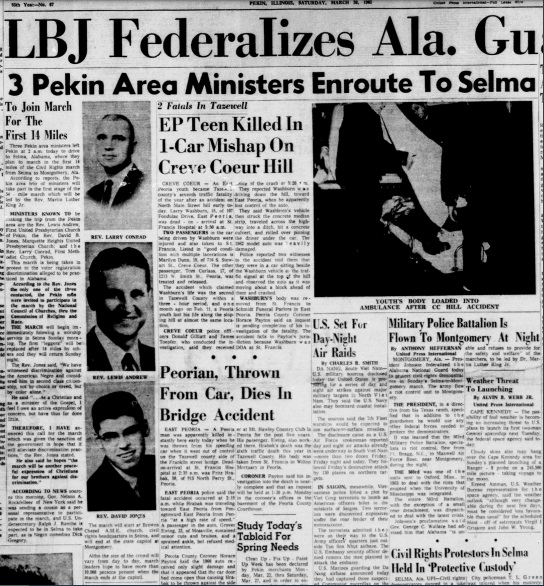

The day after Bloody Sunday, Dr. King sent out a call to clergy, asking ministers of all religions to join him in Selma. “The people of Selma will struggle on for the soul of the nation, but it is befitting that all Americans help to bear the burden. I call, therefore, on clergy of all faiths, to join me in Selma,” King said in a telegram. King’s request was further distributed by the National Council of Churches.

The next attempted march from Selma was on “Turnaround Tuesday,” 9 March 1965, when King and the marchers stopped and turned around rather than challenge the troopers blocking their way. That night, the Rev. James Reeb, 38, a Unitarian Universalist minister, was clubbed and beaten by a group of white men in Selma, dying of his injuries two days later.

Asking President Lyndon B. Johnson to protect the marchers, King and his colleagues organized a third march from Selma to Montgomery, to begin on Sunday, 21 March 1965. The march was to be conducted in stages or “legs” with a plan to reach the Montgomery state capitol steps on Thursday, 25 March 1965.

Meanwhile here in Tazewell County, the Rev. David Bebb Jones, who was then 30 years of age, pastor of Marquette Heights Presbyterian Church, and his friend and mentor the Rev. Lewis Edward “Lew” Andrew (1921-2011), then 43 years old, pastor of First United Presbyterian Church in Pekin, were busy planning a Session retreat on Friday, 19 March 1965, when they got a call at 2 p.m. from Ernest Lewis, director of the Commission of Religion and Race for the United Presbyterian Synod of Illinois, who had received King’s request for help via the National Council of Churches: “We need you in Selma.”

In a telephone interview this week on Monday, Rev. Jones told me that in the planned Session retreat he and Rev. Andrew would have focused on Ephesians 6:12-13, in which the Apostle Paul wrote:

“For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places. Wherefore take unto you the whole armour of God, that ye may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand.”

“It made no sense to us to ‘retreat to talk’ when the need was to march for justice,” Jones wrote in a 2011 tribute following Rev. Andrew’s death. Interpreting the Selma marchers’ call for help as a call from God, Andrew and Jones had meetings with their Sessions that Friday night to arrange for their temporary absence.

Andrew and Jones told their Church Sessions that they planned to march in Selma. Jones said his Session then debated whether their pastor would be there “on vacation,” or would participate with the Session’s permission as representative of his church, or would participate with the Session’s permission but not representing the church. Jones said the Session meeting was somewhat contentious, but in the end they voted 6-2 to approve his going to Selma but not officially representing the church.

That same day, Dr. King’s message was also conveyed via the National Council of Churches to Pekin First United Methodist Church, where that church’s assistant minister the Rev. Larry Eugene Conrad, then 29, answered King’s request to come to Selma. Conrad joined Andrew and Jones, and the three left Pekin together at 2 a.m. early Saturday, 20 March 1965, driving over 700 miles so they could arrive in time to join the first leg of the march.

Jones told me his wife Ann very much would have liked to have come to the march, but the Joneses then had two young girls to care for, and they weren’t sure how safe it would be. It was during their drive to Selma that the ministers heard the news that President Johnson had “federalized” the Alabama National Guard with orders to protect the marchers. Jones said some guardsmen had prior to that used violence against them, so Andrew, Jones, and Conrad weren’t sure whether the National Guard would protect them.

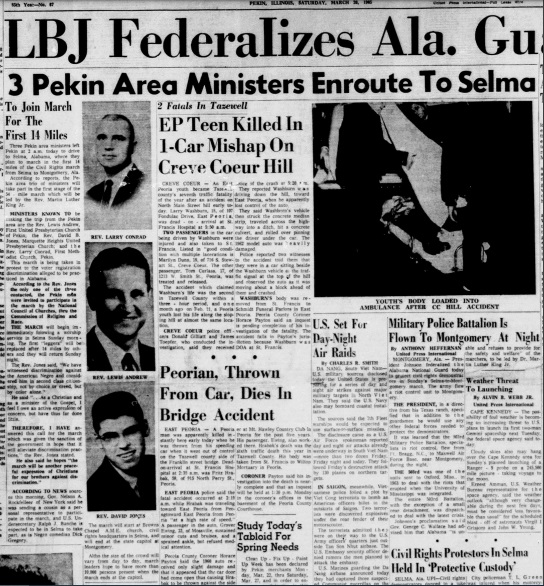

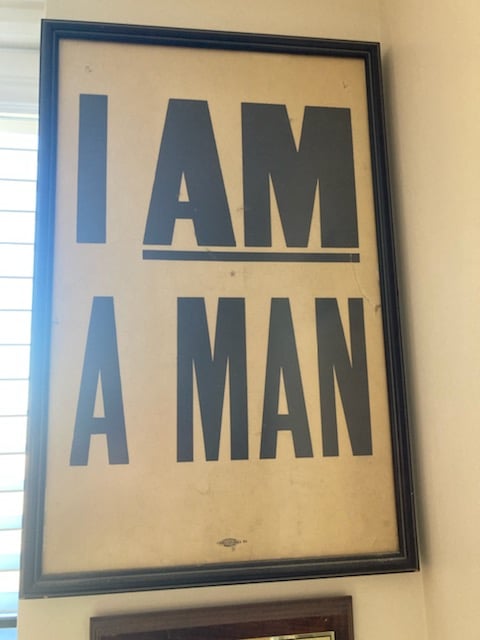

On Saturday afternoon, 20 March 1965, the Pekin Daily Times brought the front page headline, “LBJ Federalizes Ala. Guard.” Immediately below that was: “3 Pekin Area Ministers Enroute To Selma – To Join March For the First 14 Miles.” Alongside the photograph portraits of Conrad, Andrew, and Jones was this story:

Three Pekin area ministers left Pekin at 2 a.m. today to drive to Selma, Alabama, where they plan to march for the first 14 miles of the Civil Rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala.

According to reports, the Pekin area trio of ministers will take in the first stage of the 54-mile march that will be led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

MINISTERS KNOWN TO be taking the trip from the Pekin area are the Rev. Lewis Andrew, First United Presbyterian Church of Pekin, the Rev. David B. Jones, Marquette Heights United Presbyterian Church, and the Rev. Larry Conrad, First Methodist Church, Pekin.

This march is being taken in protest of the voter registration discrimination alleged to be practiced in Alabama.

According to the Rev. Jones, the only one of the three contacted, the Pekin men were invited to participate in the march by the National Council of Churches, thru the Commission of Religion and Race.

THE MARCH will begin immediately following a worship service in Selma Sunday morning. The first “leggers” will be replaced after 14 miles by others and they will return Sunday night.The Rev. Jones said, “We have witnessed discrimination against the American Negro and considered him in second class citizenship, not by choice or creed, but by color alone.”

He said, “. . . As a Christian and as a minister of the Gospel, I feel I owe an active expression of concern, but have thus far done little.

“THEREFORE, I HAVE answered this call for the march which was given the sanction of the government in hope that it will alleviate discrimination practices,” the Rev. Jones stated.

He also said he hoped “the march will be another peaceful expression of Christians for our brothers against discrimination.”

ACCORDING TO NEWS sources this morning, Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller of New York said he was sending a cousin as a personal representative to participate in the march and U.S. (sic U.N.) Undersecretary Ralph J. Bunche is expected to be in Selma to take part, as is Negro comedian Dick Gregory.The march will start at Browns Chapel A.M.E. church, civil rights headquarters in Selma, and will end at the state capitol at Montgomery.

Altho the size of the crowd will vary from day to day, march leaders hope to have more than 10,000 persons present when the march ends at the capitol.

The following day, the 22 March 1965 Pekin Daily Times ran this short article on the front page:

3 Pekin Area Ministers In First Part Of March; On Way Home Now

Three ministers from the Pekin area who left Saturday to join the “Freedom March” from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., marched the first “leg” of the 50-mile walk and are now enroute to their homes.

The Rev. David Jones, of the Marquette Heights United Presbyterian church, in talking with his wife by phone Sunday, said they had been near the front of the group at the worship service at a Selma church and had heard the speakers very well prior to leaving for the first eight miles.

Accompanying the Rev. Jones were the Rev. Lewis E. Andrew, First United Presbyterian Church of Pekin and the Rev. Larry Conrad, First Methodist church of Pekin.

No incidents were reported by the men.

After the ministers’ safe return to their families and churches, the Pekin Daily Times on 23 March 1965 ran a story about the ministers’ experiences in Selma, written by Daily Times reporter Helen Parmley and headlined, “3 Ministers Tell of Ala. March, Tension In State.” That article is reproduced in full here:

A 72-hour trip which included an 8-mile walk with the “March For Freedom” in Selma, Ala., ended today when three road-weary Pekin area ministers returned to their homes early this morning.

THE REV. Lewis E. Andrew, First United Presbyterian Church of Pekin, the Rev. Larry Conrad, First Methodist church of Pekin, and the Rev. David B. Jones, First United Presbyterian church of Marquette Heights, said that the “March” is “no carefree, joyous vacation,” but that the “attitude of the Negroes who live in this hell is seemingly unafraid; one rather of determination that this must change and that now is the time.”

These three ministers left their families in Pekin and Marquette Heights at 2 a.m. Saturday, drove 22 hours to Selma, Ala., participated in the Sunday morning worship with the freedom marchers, led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and then walked the 8-mile first stage of the 50-mile march for the cause of freedom to be allowed to vote.The march, which continued today, will end at the Alabama capitol, Montgomery.

REV. JONES said that although everything was quiet “kind of subdued,” the tension could be felt throughout the entire state. He said that the very presence of the Federal police, the desolate roads, the cursing and taunting the marchers received all have rise to the tensity of the situation.

“Our presence made it most difficult, because NOW the main thrust of southern white antagonism is not against the Selma negro, but against the outside leaders & participants,” Rev. Jones explained. “But these are a determined people.”

“Our n—–s were satisfied until you stirred them up,” was the cry heard [from] some southern whites as the marchers walked along the lonely highway.

“THE SOUTHERN Negro had accepted their life as it has been,” Rev. Andrew said, “in order to just stay alive. Now under the support of the Civil Rights movement, they have courage to throw their bodies into the struggle for the right to vote.”

Carrying this line of thought a little further, the Rev. Conrad said, “It isn’t even just the right to vote they are fighting for now – but also the right to, under law, assemble – the right to live.”

EVERYWHERE, the ministers said, they were thanked for coming to join the march. “Your presence has already changed part of the pressure, especially by law enforcement officers, that had been placed on us,” Rev. Conrad related that some of the Negroes said to them.“We didn’t have a chance until you (civil rights participants) came along,” others said, according to the ministers’ report of the march activities.

THEY TOLD about the hecklers “wherever there was room for people to stand along the roads,” and of the flags. “I only saw one American flag,” Rev. Jones stated, “and that was at the head of the march. But there were many, many Confederate flags, and flags which said, ‘one man, one vote.’”

“OUR PARTICIPATION in the march is difficult to describe,” Rev. Conrad explained. “I couldn’t do it in a 1,000 pages. These people are finally convinced that it (freedom) is now possible for them.”“We had no idea what we were getting into,” he continued. “I went because of the cause, and I felt now is the time to take a stand. I feel now that this is no longer just an emotional movement, but that it is working itself out in our country.

“The church needs to continue to provide the leadership needed.

“The march was conducted by responsible leadership – it was orderly, calm, but yet fearful.”

Rev. Jones said, “You just can’t imagine the respect they have for Dr. King. We were all packed into the assembly room, waiting – some were singing, others talking – when it was announced that Dr. King was arriving. You could feel the electricity, the respect in the air as everyone became quiet immediately.

“It’s difficult to explain the magnitude of this man with this assembly as he spoke. This will be worked out in the framework of democracy.”

REV. ANDREW said he feels the result of the participation in the march is his “firm conviction that freedom for all men is an eternal vigilance, and that it must demand the best leadership that the church can offer; for Communism is born and bred in troubled waters where responsible leadership is not at the helm. If we who love our democratic way of life lose it, it will be by default.”

“It was in Kentucky that we heard President Johnson’s news conference,” Rev. Jones said, “and we had a sense of being part of history when he said that the eyes of the nation are on Selma, and the eyes of the world are on Alabama.”

As the marchers drew closer to Montgomery, the Pekin Daily Times on 24 March 1965 ran a page 2 follow-up story by Helen Parmley about the three Pekin-area ministers who had participated in the march’s first leg, headlined, “Ministers Describe Types Of Persons Who Joined Selma Freedom March.” Following are extensive excerpts from that article:

Three Pekin area ministers who do not consider themselves as “experts” on the Civil Rights movement in our country, but who traveled to Selma, Ala., this week to join the “Freedom March” for voters rights today began to unravel the details of their participation with thousands of others who seemed to pour out of nowhere.

Joining the first leg march led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Sunday, were the Revs. Larry Conrad, First Methodist church, Pekin; Lewis E. Andrew, First United Presbyterian church, Pekin; and David B. Jones, Marquette Heights United Presbyterian church.

THESE MEN left their families in the middle of the night to drive a rough 1,000 miles to their destination, where they were to walk eight miles, to be cursed at, to be taunted, laughed at, scorned. There were times when they were fearful. They had read about peaceful demonstrations that didn’t always remain peaceful. They had read about a minister who died from a beating administered during a demonstration.

Why did they go?

“Before I went, I was convinced that I should – because of the news reports and statements by officials, of government and church, of discriminatory practices that are simply not a part of our democracy,” Rev. Jones said. “And now that I’ve been there I’m even more convinced it was the thing to do.

“I WISH THESE discriminatory practices would end by appeals of reason or conscience. But the history of the struggle for civil rights has pointed out that the only significant progress that has come, has been made by drawing attention to such discrimination by demonstrations and then pressure applied by many groups – only they brought action to alleviate the problem.”“Reports do not give a clear picture. How these Negroes have survived in the face of oppression, threat, and constant fear of their lives, is beyond our imaginations. And they have deep integrity in spite of it all.”

REV. CONRAD said, “Every great calling in the Bible was a call to service to humanity. A call from the people for help is a call from God.

“Selma was a clear-cut place to witness for Civil Rights in the nation, not just the South. The march said something to the world specifically. There is a positive approach being taken in this responsible leadership that needs to be done everywhere – to get the right of the Negro to his freedom.”

“It is man’s inhumanity against man,” Rev. Andrew said. “The South practices discrimination openly, admittedly, flagrantly.”

What did you find to be the situation, regarding voter registration, when you arrived in Selma?Rev. Andrew pointed out that in Lowdnes County the population is 81 percent Negro with “only two Negros registered to vote.”

“WE TALKED with one man,” they explained, “a well-educated colored minister, who was number 2,126 to register. He explained, as did others, that the registration office is open two days a month, on work days – making it probable that the man who takes off work to register loses his job. If he does take off from his job, he then stands in line at the registration office, and the numbers are called, but not always numerically. If the registrar with that number is there, and if his number is called, he may then take a test. If the number is called, and he is not there, his number goes to the bottom. A maximum of 100 persons are registered a day. This, however, is an improvement by court order, brought about after demonstrations were started. Before that, only 12 a day were registered, and the first 10 or 12, in line each day were white persons. Those who take the test are then notified if they are acceptable – if not, they may be told they missed a question or that they are morally unacceptable. They are not told what question they missed – questions a lawyer might be able to answer.”

“HOWEVER,” the ministers pointed out, “the Negroes now have the courage to register, the courage to eat in some cafes.”

“They are now not afraid to register, because of the Civil Rights movement, the backing of the people, the assurance of the government, and they believe now that these rights should be theirs, can be theirs, and will be theirs.”

. . . .“The movement, however, is under the capable, Christian leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King. The cause is just, and the approach is right – to work to strengthen, to make real, the basic elements of democracy.”

THE THREE MINISTERS from Pekin were fed, housed, and cared for by the Negro church in Selma. They visited a Negro home which they described as being a very nice, very comfortable, well-kept home built by the government. They also saw the “ghetto” of shacks, unpaved streets, filth in which many of them live.

What of the people who believe the church has no place in this social movement?

“Apart from the Negro community, there is no other group active except the church,” the ministers reported. “Many say this is no place for the church. But those who say church shouldn’t be involved are also persons who say, or believe, there is no need to fight for civil rights.

“Since leaders will come – the vacuum will be filled – the church must re-dedicate itself to active involvement.”

THE THREE MEN did not walk together during the march, but split up to meet more people. They returned to Pekin well-sunned, with one of them, not anticipating the bright, southern sun, sun-burned.

During the eight-mile, first day step of the march, the men said they never saw any violence, retaliation, or verbal combat on the part of the marchers, as they were heckled beyond imagination.

All three spoke in glowing tones about the leader of the movement, Dr. King, who they say has the “grasp” of the fight for freedom, and the complete loyalty of the people. They believe that active support must be given to the non-violent approach to freedom for all people.

STATE POLICE took pictures of the marchers, the ministers said, and these they believed might be developed and turned over to the employers of these marchers, putting their jobs in jeopardy.

This successful third march from Selma to Montgomery is credited with supplying spiritual and political impetus for the passage of federal legislation to protect the voting rights of African-Americans. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was presented to Congress on 17 March 1965, between “Turnaround Tuesday” and the start of the third Selma march. President Johnson signed the bill into law on 6 Aug. 1965.

In our phone conversation on Monday, Rev. Jones said of his experience at the Selma march, “As you can guess, it changed a person’s life – it certainly changed mine.”

In his 2011 reflections and memories he wrote upon the passing of his friend and colleague Rev. Andrew, Jones said, “With family support, we left in the night and drove to Selma, marching the first day. It was dramatic, tense, controversial, and ultimately changed the United States.”

Over the years leading up to the moment he decided to join the march in Selma, Rev. Jones’ already had developed strong and thoughtful convictions regarding social justice and race informed by his Christian faith. While attending McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago, Jones even met Martin Luther King Jr. when King visited the seminary to preach on race on 20 April 1959. Watching civil rights events unfold in the early months of 1965, Rev. Jones on 15 March 1965 organized his thoughts and prepared a two-page statement on the Civil Rights Movement for the Session of his church in Marquette Heights, concluding “as a Christian, and particularly as minister of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, that I can no longer remain as inactive in this movement as I have been in the past.”

In our phone conversation, Rev. Jones said he was very grateful that the members of his church in Marquette Heights supported his choice to march in Selma. “They were supportive. It was amazing. Some ministers went, and they were ‘crucified’ for it. But that little church was wonderful. They stood with me. It was remarkable,” Jones said.

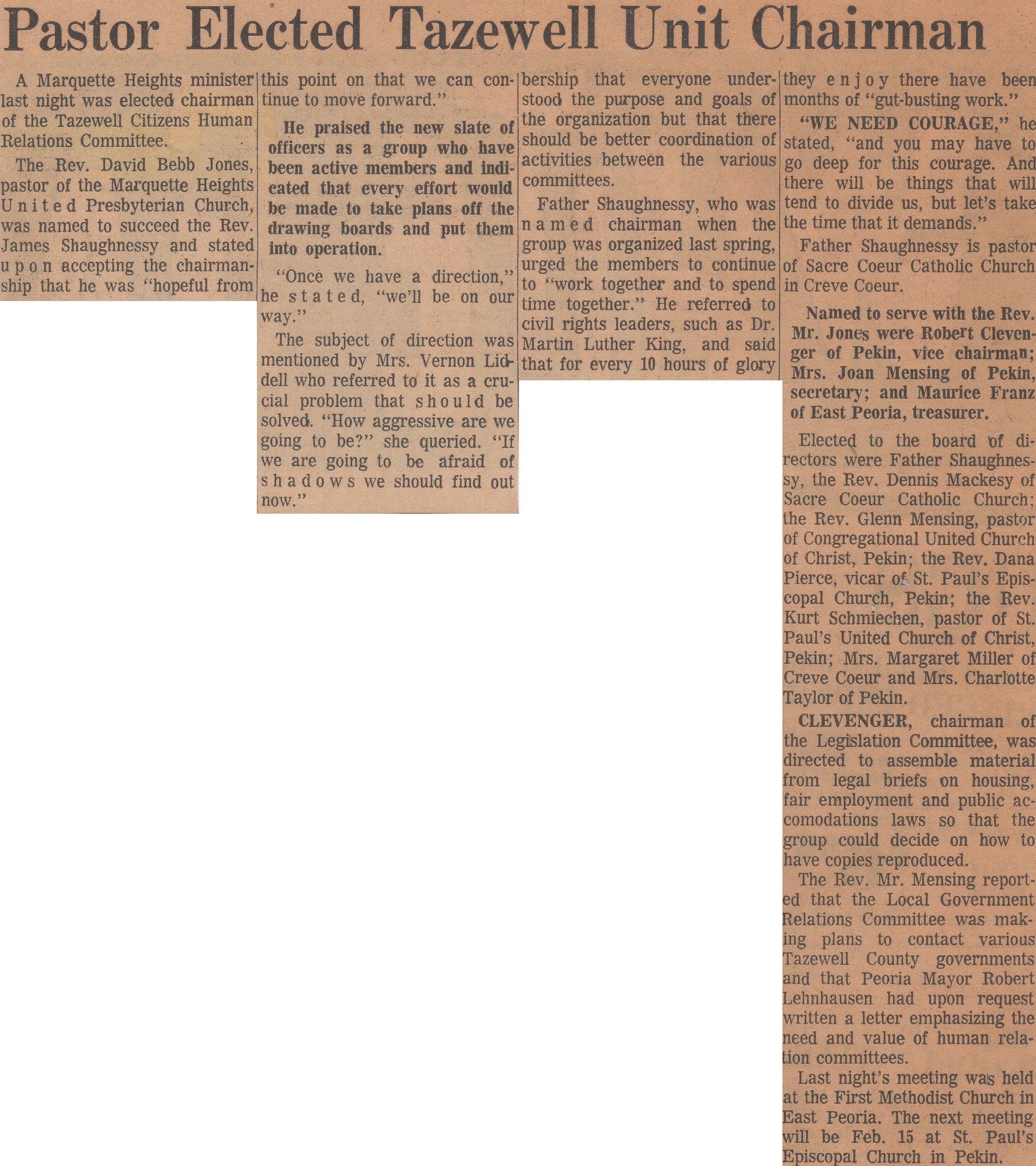

Jones said he, Andrew, and Conrad returned from Selma with a stronger commitment to work for social justice. One local outcome of the Selma marches was the founding of the Tazewell County Human Relations Committee in the spring of 1965. Jones said he, Andrew, and Conrad visited Tazewell County’s clubs, churches, and volunteer organizations, telling of their experiences and bringing attention to the county’s absence of African-Americans and troubled race history.

Jones was elected chairman of the Committee on 15 Jan. 1966, succeeding Father James Shaughnessy (1913-1998), then pastor of Sacre Coeur Catholic Church in Creve Coeur and who was named to head the Peoria Social Action Institute in 1942. At the same time, Pekin attorney Robert Clevenger was elected vice chairman, Mrs. Joan Mensing of Pekin was elected secretary, and Maurice Franz of East Peoria was elected treasurer. In May that year, Peoria Chapter NAACP President John H. Gwynn (1929-1996), whom Jones had met at the Selma march, addressed the Committee and challenged them to issue a statement “that it would welcome Negroes in the county to work and live like any other persons.” The Committee was able to document county housing, fair employment, and public accomodations laws, bringing to light racist “protective covenants” in Tazewell County such as one in a Marquette Heights subdivision that classified non-white persons as “nuisances” and barred them from living there unless they were domestic servants working for a white family.

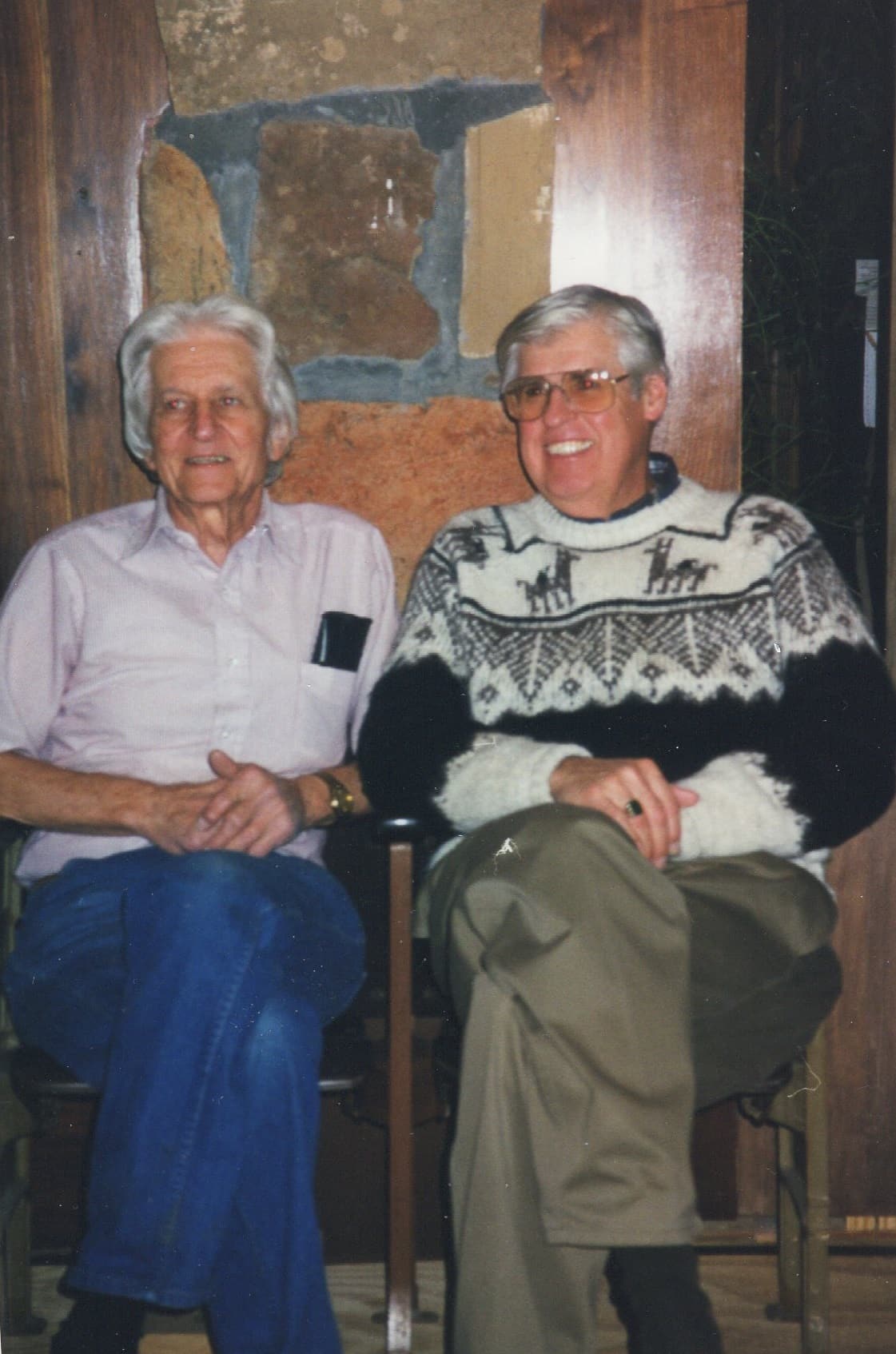

Jones said that he, Andrew, and Conrad were inspired by their experience marching in Selma to devote their Christian ministries to working for a more just society, even as their work led them away from Tazewell County. Andrew eventually returned to his native Oklahoma where he passed away in 2011 at the age of 89, just 22 days shy of his 90th birthday. Conrad, who is now 88, moved out to Blaine, Washington, before settling in Texas, while the ministry of Jones, who is now 89, took him to Peoria, then Western Springs, Illinois, and at last in retirement in Downers Grove, Illinois.

In an email to me on 10 Feb. 2024, Jones wrote:

“I left the Marquette Heights United Presbyterian Church in the summer of 1966 and became the associate pastor of the First Federated Church of Peoria for four years, leaving in October 1970 to become the pastor of the Presbyterian Church of Western Springs, Ill., for thirty years, retiring on Jan. 1, 2001.

“I have not been in contact with Rev. Larry Conrad through these decades, but did reach out to him in 2011 when Lew died and we talked from his home in Dallas. . . . What I do remember from that 2011 conversation is that Larry remained very involved in racial justice and peace issues through his life.”

My own efforts to contact Rev. Conrad have not been successful. But continuing with Jones’ words in his email, Jones spoke further of Rev. Andrew:

“We were incredibly close in the early years as he was my mentor in ministry, as well as colleague and friend. Our ministries in Pekin and Marquette Heights ended in 1966 as Lew went to the Presbyterian Synod of Illinois as a staff person in Race Relations and I went to Peoria, but we kept in close touch through the years. We worked together on racial justice issues during my time in Peoria. Lew became a school counselor after his church leadership and retired to his home land of Oklahoma in 1978. We were in annual contact through these years and shared commitments to ministry and justice. We last visited in 1998 and I wrote several pieces about our shared lives at that time and at the time of his death.”

Reflecting on his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, Jones wrote in his email that “it surely is more modest on reflection than it could have been. Nevertheless, participating in the Selma March was surely the turning point in my ministry and in my convictions for racial justice and the never-ending quest for full freedom for all persons.”

Taking a broad and humble view on whether his, Andrew’s, and Conrad’s civil rights efforts made any difference, Jones told me in our phone conversation, “I don’t know if it did any good” — yet at the time they were moved to do what they could, he said.