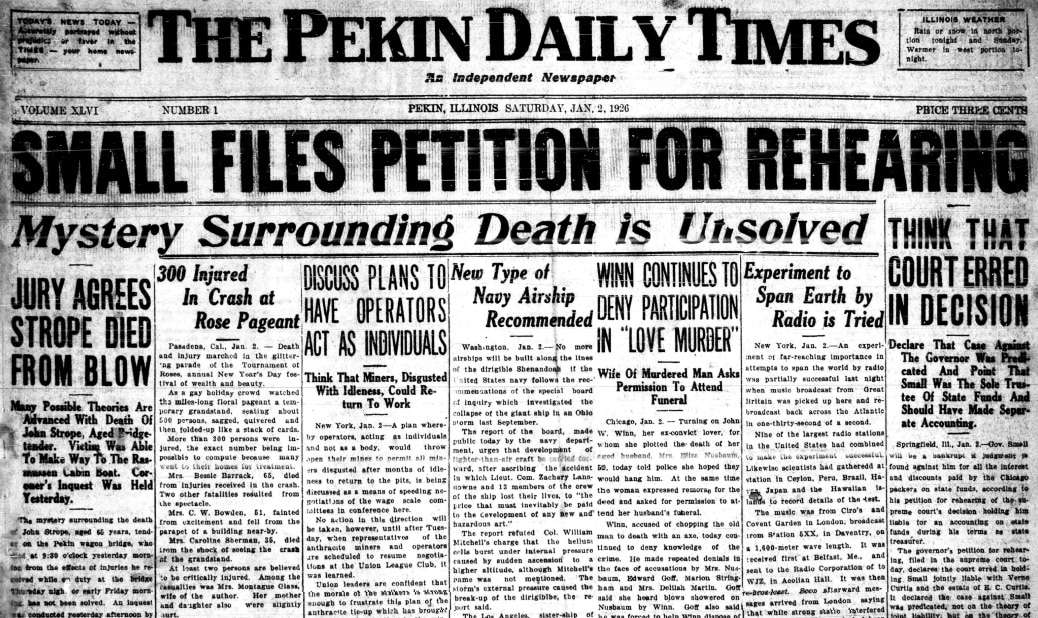

With this post to our Local History Room weblog, we continue our series on a pair of sensational deaths that occurred in Pekin, Illinois, during the Prohibition Era. The Local History Room columns in this series, entitled “The Third Degree,” originally ran in the Saturday Pekin Daily Times from Sept. 15, 2012, to March 2, 2013.

THE THIRD DEGREE

By Jared Olar

Library assistant

Chapter Five

Deputy Skinner issues denials

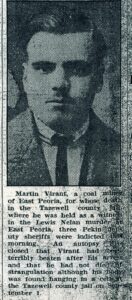

On Sept. 1, 1932, Martin Virant of East Peoria was found dead in his cell at the Tazewell County Jail in Pekin. The Tazewell County Sheriff’s Office claimed Virant had committed suicide by hanging.

It was just the night before, testifying under oath as a witness at the inquest into the murder of Lewis P. Nelan, that Virant had boldly accused Deputy Charles O. Skinner and other deputies of savagely beating him.

Two autopsies and the findings of an expert Chicago criminologist were all in agreement that Virant did not die from hanging, but rather had succumbed to numerous severe injuries he had suffered in a beating. Armed with the results of the investigation of Virant’s death, on Sept. 5 Tazewell County State’s Attorney Louis P. Dunkelberg swore out a warrant for Skinner’s arrest.

On Tuesday, Sept. 6, word spread that Skinner, who was in Aurora that day on official business, would be arrested for murder, and a crowd gathered in and around the courthouse in downtown Pekin.

Concerned that the crowd could become a lynch mob, Sheriff James J. Crosby “as a measure of precaution swore in a number of special deputies,” according to the Sept. 7, 1932 Pekin Daily Times. “These deputies remained on duty about the courthouse and mingled with the crowd during the evening in an effort to judge its temper, some of them remaining on duty all night.”

As another precaution, Pekin Police Chief Ralph Goar arranged to serve the arrest warrant as soon as Skinner returned from Aurora, before anyone in the crowd was aware of his return. Goar offered Skinner a choice between surrendering at the sheriff’s office and being held in Pekin, or surrendering in Peoria and being held in the Peoria County Jail.

According to the Sept. 17, 1932 Peoria Journal, when Goar told him of the warrant for his arrest, “Deputy Skinner was much affected, slumped down in the seat of his auto and cried. Chief Goar is quoted as saying that Deputy Skinner remarked to him: ‘Well, they’re not going to saddle it all onto me.’”

Terrified of the gathered crowd, Skinner asked to be taken to Peoria. He also asked Goar not to drive through East Peoria, where anger against Skinner had been aroused by the allegations of what he had done to Virant.

According to the Sept. 7, 1932 Daily Times, after Skinner was brought to the Peoria County Jail, State’s Attorney Dunkelberg and Coroner A. E. Allen questioned him for almost an hour.

Of that interview, the Times reported, “Skinner is quoted as denying emphatically that he ever struck, beat or kicked Virant or stood on the man’s neck as Virant had declared at the Nelan inquest.

“’I did not hit the man at any time,’ he declared in reply to a direct question.

“Ask[ed] who did, Skinner declared, ‘I don’t know any one who did.’

“When asked why Virant had named him at the Nelan inquest, Skinner’s answer was that he supposed it was because he was the only officer Virant knew by name, he having known him for several months.”

In a story on the front page of the Sept. 8, 1932 Pekin Daily Times, Virant’s brother-in-law Frank Franko affirmed that Virant and Skinner knew each other, and said that Virant thought very little of Skinner’s character. “Martin often say to me, ‘Skinner is a bad man,’” Franko told the Daily Times.

Further on, the Sept. 7 Daily Times story said, “Asked to explain why Virant was handcuffed when brought to the Nelan inquest, while three other men charged with Nelan’s murder were not handcuffed, Skinner said that Virant had attempted to escape on the way from the jail to Kuecks Funeral home, where the inquest was held, and that he had put the handcuffs on him. He denied shoving the man or treating him roughly at any time while taking him to or from the jail.

“It was pointed out to Skinner that Virant probably was dead when he was hanging in his cell.

“’Well, if he was hung up there by somebody, it wasn’t me,’ the deputy replied. ‘Somebody else done it.’

“In answer to further questions, Skinner explained that Virant had given himself up in East Peoria to Skinner when the latter went there to question him about the Nelan case.

“’Was he beaten up then? Did he have black eyes or a swollen ear?’ the deputy was asked.

“’I didn’t notice.’

“’But you did notice signs of beating when Virant was at the Nelan inquest, didn’t you?’

“’No, I didn’t. When Coroner Allen cut his body down, I saw a mark on his forehead, but that’s all I noticed.’

“Coroner Allen said it was peculiar that Virant had no marks on him before he was arrested and showed many marks after he was in the custody of the sheriff’s force, yet the latter made no effort to find out how the man came to be injured. Skinner said he didn’t know about this.

“At the end of the questioning, Skinner voluntarily denied again that he had ever beaten Virant.”

Next week: Skinner sees the judge.