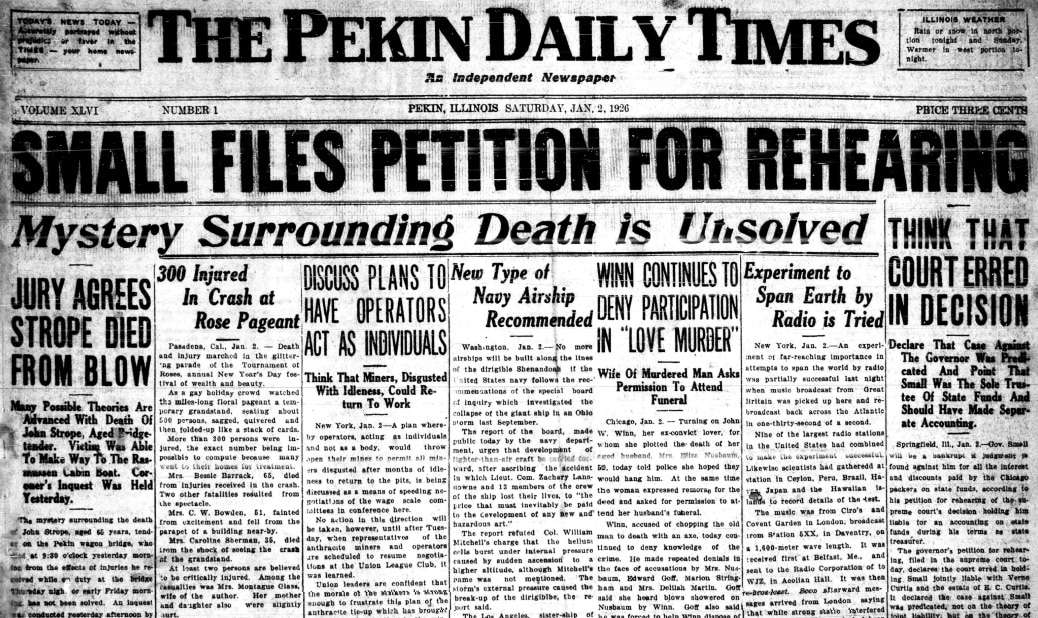

With this post to our Local History Room weblog, we continue our series on a pair of sensational deaths that occurred in Pekin, Illinois, during the Prohibition Era. The Local History Room columns in this series, entitled “The Third Degree,” originally ran in the Saturday Pekin Daily Times from Sept. 15, 2012, to March 2, 2013.

THE THIRD DEGREE

By Jared Olar

Library assistant

Chapter Twenty

‘We, the jury, find the defendants . . .’

On Thursday, March 2, 1932, the defense rested its case in the manslaughter trial of Tazewell County Sheriff’s Deputies Charles Skinner and Ernest Fleming, who were accused of the death of jail inmate Martin Virant.

As the defense lawyers concluded the efforts to exonerate Fleming and Skinner, they delivered a compelling attack on the credibility of the state’s star witness Elizabeth Spearman, whose testimony implicated Skinner and Fleming in the severe injuries Virant had suffered.

In the end, the defense attorneys moved to have the whole of Spearman’s testimony quashed and stricken from the record.

Though Spearman, as an accused criminal and jail inmate, probably had just as great a problem with her credibility and accuracy as most of the defense’s jail inmate witnesses, nevertheless, Menard County Judge Guy Williams granted the defense’s motion.

In closing arguments lasting the entire morning of March 3 – arguments the Pekin Daily Times described as a “powerful oration” – defense attorney Jesse Black, reveling once more in the courtroom drama at which he excelled, denounced and ridiculed the state’s case.

“At times the attorney could be heard a block away as he shouted his denunciation of an attempt to deprive men of their liberty and ‘put them behind grey walls’ without any proof whatsoever,” the Daily Times reported.

In contrast, Tazewell County State’s Attorney Nathan T. Elliff delivered his closing arguments in a calm and quiet demeanor. “As to doubts about this case, I have just two doubts in my mind. One of these is whether this is a murder or a manslaughter. The other doubt in my mind is whether or not we’ve got all the defendants that are guilty,” Elliff said.

After closing arguments, Judge Williams gave instructions to the jury, reminding them to disregard Spearman’s testimony. The case went to the jury at 3:30 p.m. on March 3.

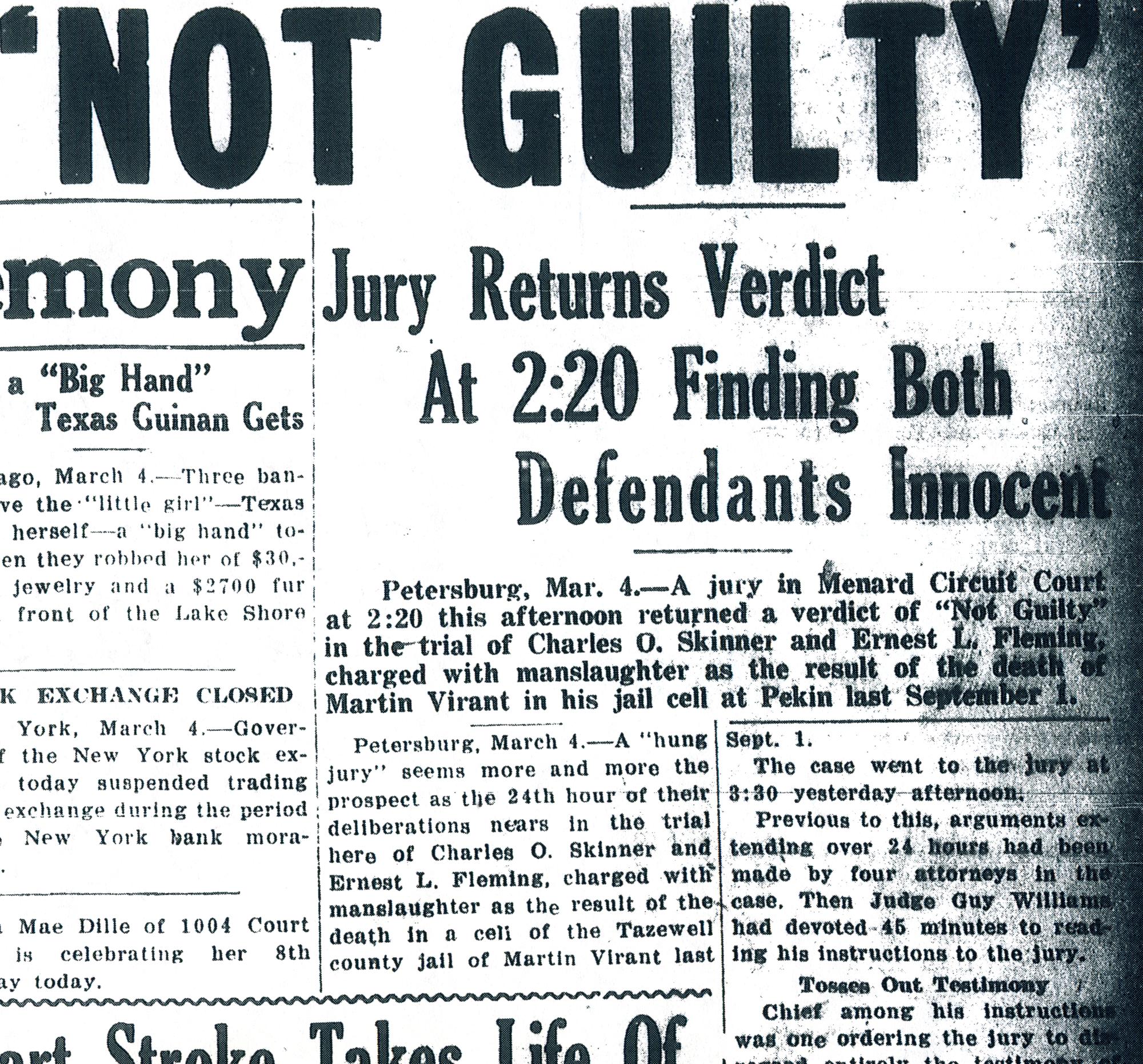

The jurors came back with a verdict at 2:20 p.m. Saturday, March 4, 1933.

“JAIL DEATH JURY SAYS ‘NOT GUILTY,’” ran the Pekin Daily Times headline that day.

Both deputies were found not guilty of all charges. It was a stunning victory for Black and his fellow attorney William J. Reardon (though Reardon was called away from the trial at the very end due to the death of his brother in St. Louis on the night of March 2). Their decades of courtroom experience obviously had served them well.

And it was an embarrassing defeat for Elliff, whose youth and inexperience were frequently evident during the course of the trial.

“In Attorneys Reardon and Black, the defense has a pair of crafty barristers of long experience in court cunning. They know when to object and when to be silent,” wrote Pekin Daily Times reporter Mildred Beardsley in the Monday, Feb. 27, 1933 edition of the newspaper.

“They know when to shout in feigned anger and when to ‘Pooh! Pooh!’ in apparent disdain,” Beardsley continued. “These things, I suppose, are learned thru years of experience. More than once Judge Williams has told the youthful prosecutors that he would have sustained them if they had objected.”

In the final analysis, however, perhaps neither the inexperience of the prosecutors, nor the talent of the defense attorneys, nor the valiant attempts of the defense to explain away the convincing forensic evidence that Virant had been beaten and had not died of hanging, were that important in the exoneration of Fleming and Skinner.

The greatest challenge the prosecutors faced wasn’t proving that Virant had been beaten while in custody at the jail, nor that he had already died prior to being hanged – it was proving that Fleming and Skinner were connected to the crime.

Without Virant’s own testimony at the inquest of Lew Nelan, and without Spearman’s testimony, the jury had no evidence that Fleming and Skinner, or any other deputy, had done violence to Virant or faked his suicide. Proving that Virant was the victim of a crime was one thing. Proving that the crime had been committed by Fleming and Skinner was something else altogether.

And so the trial was over. Fleming and Skinner were free men.

Nevertheless, the tragedy of Virant’s death was nowhere near its final act.

Next week: Petitions for impeachment.