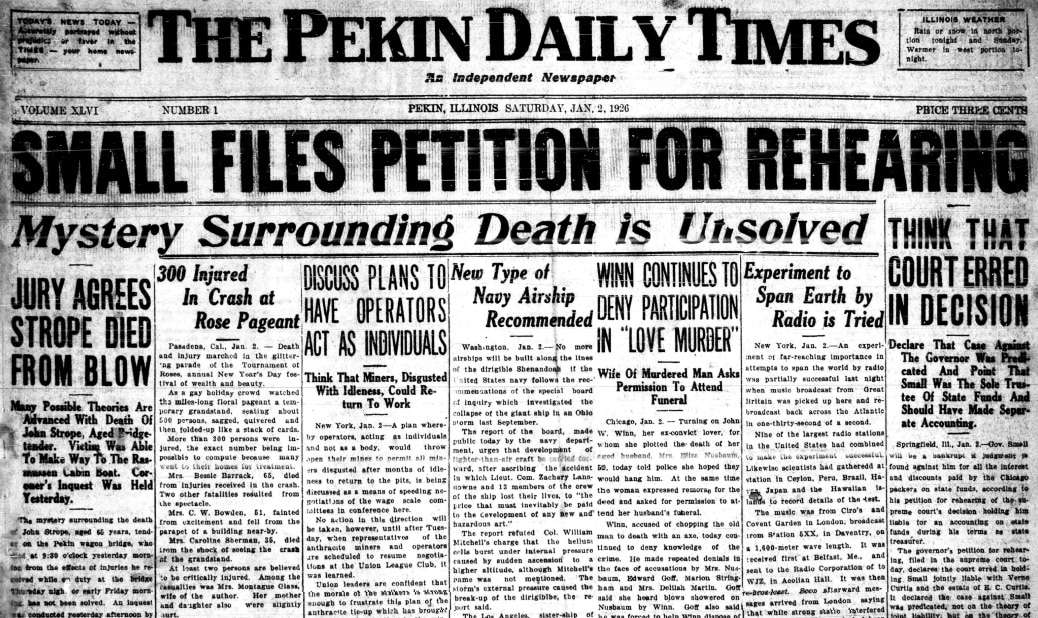

With this post to our Local History Room weblog, we continue our series on a pair of sensational deaths that occurred in Pekin, Illinois, during the Prohibition Era. The Local History Room columns in this series, entitled “The Third Degree,” originally ran in the Saturday Pekin Daily Times from Sept. 15, 2012, to March 2, 2013.

THE THIRD DEGREE

By Jared Olar

Library assistant

Chapter Seventeen

Clash of the medical experts

Key to the prosecution of Tazewell County Sheriff’s Deputies Ernest Fleming and Charles Skinner for the beating death of jail inmate Martin Virant was the testimony of several medical experts, chief of whom were former Tazewell County Coroner Dr. Arthur E. Allen and Chicago criminologist Dr. William D. McNally.

During the trial of Fleming and Skinner in late February 1933, Allen and McNally gave hours of testimony in order to establish for the jury that after Virant died, his body exhibited extensive internal and external injuries – more than 30 different injuries, including a broken rib, Allen testified – that obviously were not the result of a hanging, and that Virant in fact had died of those injuries before he was hanged.

Other prosecution witnesses had testified that Virant had no visible injuries when he first was brought to the Tazewell County Jail, but the following day, at the inquest of murder victim Lew Nelan, Virant was seen to have several bruises and wounds about his head and neck. Allen corroborated their testimony, describing the injuries that he saw at the Nelan inquest, and telling the jury that Virant was “nervous and excited” and “in pain and distress,” and that he spoke in a voice that “was quite loud.”

On Thursday afternoon, Sept. 1, 1932, around 2:15 p.m., Allen entered Virant’s cell and saw his body hanging in the northeast corner of the cell. Virant’s feet were flat on the floor. Fleming was there, but neither he nor any other member of the jail staff had attempted to cut Virant down. Allen then did so.

“I took my pocket knife in my right hand and slipped my hand around his waist to ease the body to the floor,” Allen said. Virant was a short man and of slight build, and his body did not strike any object as Allen eased it to the floor. Virant had no pulse, but Allen began artificial respiration. “I knew I could get no response but I thought there might be some life left.”

“The body was warm and I heard Deputy Sheriff Fleming say, ‘He couldn’t have been hanging very long.’”

Most troubling, Virant’s body showed none of the usual signs of a hanging death. “Dr. Allen told that he had occasion to observe the body of the deceased closely while performing artificial respiration and that the face had the natural death pallor. The face showed evidence of there being no circulation. He said that the tongue was not swollen neither was there a collection of fluid in the man’s mouth,” the Daily Times reported. “The eyes were not protruding but were partly closed,” Allen testified.

If Virant had died of hanging, Allen said, his body should have had a dark discoloration of the face from the neck up to the face and scalp, a dark discoloration of the lips and tongue, and a swollen and protruding tongue. There could be no doubt, then, that Virant had been hanged after he had lost all blood circulation to his head.

Pekin physicians L. F. Teter and L. R. Clary, who conducted two autopsies on Virant’s body at Allen’s direction, also provided testimony that showed Virant was dead before he was hanged. In particular, they found that Virant had suffered a brain injury due to a concussion. McNally also reiterated his findings at great length, assuring the jury that Virant could not have died of hanging, but rather had died as the result of a vicious beating.

The defense attorneys labored valiantly to rebut the state’s expert testimony, and hostility was at times evident between Allen and Pekin attorney Jesse Black as he persisted in his vain attempts to trip Allen up.

The defense also countered the prosecution’s expert testimony with medical experts of its own, Dr. C. G. Farnum of Peoria, Dr. T. M. Scott of Peterburg, and Dr. R. B. H. Gradwohl of St. Louis, who sharply contradicted key points of the conclusions of Allen, Teter, Clary and McNally.

In particular, Gradwohl, a coroner who had investigated numerous suicidal hangings and had even personally conducted six legal hangings, bluntly rejected the results of McNally’s investigation as “faulty observation.”

According to the state’s witnesses and experts, Virant had been brutally beaten while in custody at the jail, and finally had succumbed to a kind of “shock” resulting from the severity of his wounds.

But, in his testimony on March 1, 1933, Farnum said that Virant could not have been in “shock,” because the autopsy results as well as witnesses at the jail had established that Virant had eaten a meal within an hour of his death. Virant also allegedly attempted to flee when he was taken from the jail to the Nelan inquest. A man suffering from shock could not have done either of those things.

On that point, Farnum was correct. Virant did not die of shock. Based on the autopsies and the known circumstances of Virant’s death, more likely the immediate cause of his death was the brain injury he suffered when the deputies tortured him.

Farnum and Gradwohl also told the jury that embalming alters a dead body in ways that could affect an autopsy’s findings. This was potentially important, because both of the autopsies conducted by Teter and Clary, as well as McNally’s examinations, took place after Virant had been embalmed. Farnum implied that even the apparent evidence of Virant’s concussion and bleeding in his brain could have been caused by the embalming.

Finally, Farnum and Gradwohl contradicted the conclusion of the state’s experts that Virant’s bruises had been inflicted prior to his death. They explained that if a body is injured just before death or very soon after death (but before blood circulation has been lost), bruising can result. This would form an important part of the defense’s alternate scenario of how Virant died and why his body appeared to have been horrifically beaten.

However, none of the defense’s experts attempted to counter the evidence that Virant showed none of the usual signs of a hanging death. The defense attorneys would attempt to destroy the credibility of that evidence through other means.

Next week: The defense pleads its case.