With special Juneteenth-related events planned next week that will honor the memory of Nance Legins-Costley of Pekin, this week seems like an ideal time to review some recent advances in research regarding the African-American families of Ashby, Chavous, Chase, and Harris who appear in many records of Pekin and Peoria during the 19th century.

This particular line of research that I’ll present today involves a genealogical “brick wall” regarding a member of the Ashby family that I was able finally to knock down — and who did I find standing on the other side of that wall but none other than famed Peoria abolitionist Moses Pettengill himself!

This latest discovery is about Lavinia Ashby (1832-1920) of Peoria, whom I previously had tentatively identified as a daughter of Dr. James Ashby, first African-American physician of Fulton County, Illinois, and thus probably a sister of Pvt. Nathan Ashby of Pekin and Peoria, a Juneteenth eyewitness who is buried at the former Moffatt Cemetery).

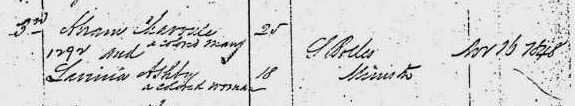

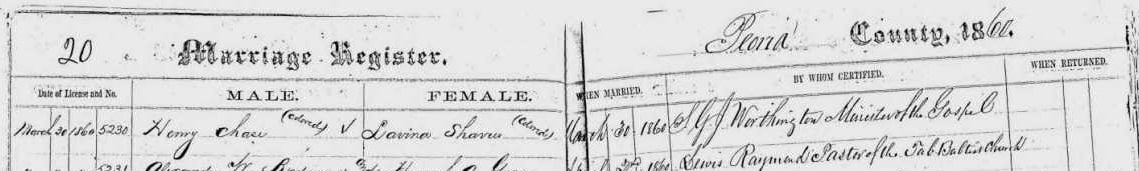

Until last month, all I knew about Lavinia was the information gleaned from her 1848 marriage record, which tells us that on 3 Nov. 1848 in Peoria County, Lavinia Ashby, “colored woman,” married a “colored man” whose name in the marriage record is amazingly difficult to read. To my eye, his name looks like “Knam Charoule,” but a possible reading of that cramped cursive writing could be “Abram” or “Hiram Charoute.”

Given the date and the location of this marriage, and given that other probable children of Dr. James Ashby were then living in Peoria, I tentatively identified Lavinia as another child of Dr. James Ashby.

We no longer need to speculate. Last month I found Lavinia’s 1920 death record, which provides specific dates of birth and death for her, and tells us when and where she was buried. She is interred in historic African-American Lincoln Cemetery in Blue Island, Illinois. Best of all, the death record tells us that she was born in Fulton County (where else?) and that her father’s name was JAMES ASHBY. Well, the only African-American James Ashby in Fulton County who could be her father is Dr. James Ashby.

This is the first documented parentage for a child of Dr. James Ashby that I have found — for the rest of his probable children, we can only make inferences from circumstantial evidence of varying degrees of weight giving us reason to believe they were his children.

Where does Moses Pettengill come in, you ask?

Well, Lavinia’s death record and the 1900 U.S. Census both tell us that after her first marriage ended (presumably due to Abram’s death), she later remarried to an African-American of Peoria named Hilliard H. Harris (1831-1910), who worked as a gardener. Hilliard Harris is buried in Springdale Cemetery. I have been able to trace him through Peoria census and city directory records starting in 1860.

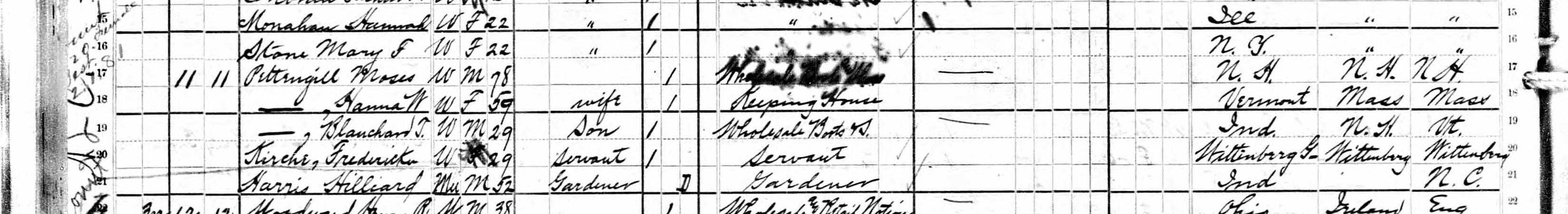

When I saw the 1880 census record, though, the endorphin rush just about sent me floating out of my chair: that year, Hilliard Harris was working as a gardener for – and living in the house of – Moses Pettengill (1802-1883), who established Peoria’s Underground Railroad! (We have previously told the story of Peter Logan, whom Susan Rynerson of the Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society identified as one of Tazewell County’s earliest African-American landowners, finding that Logan named Moses Pettengill to be the executor of his estate.)

I have found the marriage record of Hilliard and Lavinia in La Salle County, Illinois — they married 10 March 1885, and Ancestry.com has transcribed Lavinia’s name in that record as “Lavina Chase.”

Why is her surname in that record given as “Chase”? Could it have something to do with the difficult-to-read surname of her first husband Abram?

No. The 1885 La Salle County marriage record calls her “Chase” because her second husband, whom she married on 30 March 1860 in Peoria – was Henry Chase of Peoria. The marriage record of Lavinia and her second husband Henry Chase calls her “Lavina Shavus.”

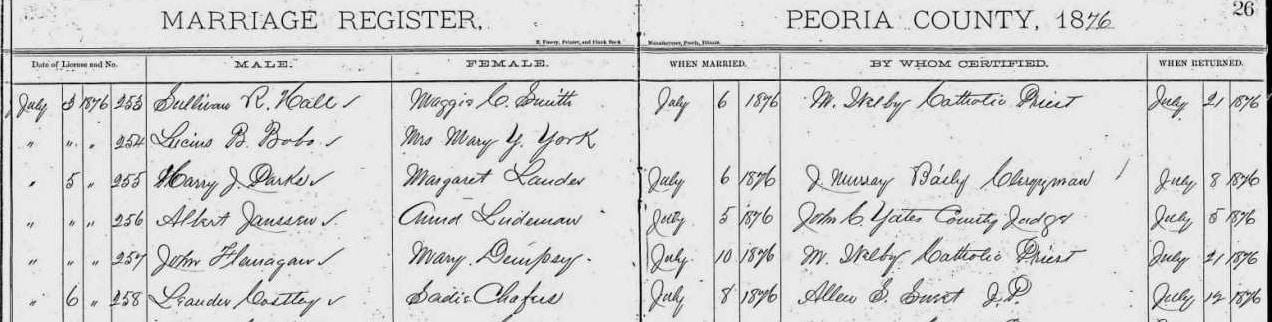

And that enables us to determine the correct reading of the name of Lavinia’s first husband Abram – it’s neither “Charoule” nor “Charoute,” but Chavouse or Chavous, pronounced “Shavus.” That fact, in turn, raises the possibility that Lavinia’s husband Abram Chavous was related to the Sadie “Chafers” or Chavers who married Leander Costley, second son of Nance Legins-Costley of Pekin. “Chavers” is a variant spelling of “Chavous,” and Leander’s wife Sadie was about the right age to have been a daughter or niece of Abram Chavous.

It should also be remembered that Lavinia’s second husband Henry Chase earlier had married Elizabeth (Ashby) Shipman on 8 March 1854 at the African M. E. Church in Peoria. I had previously suggested that Elizabeth could have been a daughter of Dr. James Ashby of Liverpool Township, Fulton County. It appears that Henry Chase married two Ashby sisters.

This in turn relates to something else that I discovered about Lavinia’s third husband Hilliard H. Harris. In the 1860 U.S. Census, Hilliard is shown living in Peoria, and in his household is a 10-year-old boy named “Carles T. Shipman” (an error for Charles), born in Illinois. I had already noted that the 1855 Illinois State Census for Peoria had enumerated a boy under the age of 10 in the household of Henry Chase. I believe “Carles” T. Shipman is probably that boy of the 1855 state census, who thus would be a grandson of Moses and Milly Shipman, of whom Susan Rynerson and I have written and researched so much. This same Charles Shipman appears in the 1900 U.S. Census as a resident of Minneapolis, Minnesota, living in the same domicile as James Willis Costley (or Cosley), younger brother of Leander Costley.

In summary, not only do we now have documented evidence of Lavinia Ashby’s paternity, but this new information gives a fuller picture of the African-American Ashby family and their relatives in Peoria during these decades – and on balance, it tends to further strengthen my hypothesis that Pvt. Nathan Ashby, Juneteenth eyewitness, was a son of Dr. James Ashby.