Here’s a chance to read again one of our old Local History Room columns, first published in November 2013 before the launch of this blog . . .

The village of Mackinaw in eastern Tazewell County occupies a special position in the county’s history. As this column has noted previously, Mackinaw was the first seat of government for Tazewell County, and the first county courthouse was erected in Mackinaw.

One of the most important sources for the history of those days is Charles C. Chapman’s “History of Tazewell County.” Also among the Pekin Public Library’s Local History Room sources that tell of Mackinaw’s history is “Mackinaw Remembers 1827-1977,” edited by Gladys Garst. The story of Mackinaw’s founding is told on the first two pages of that book, along with a glance back at the prehistory of the Mackinaw area.

“The proof and importance of marks in our Indian cultural heritage,” this volume says, “lies in the fact that Dr. W. H. Holmes, Curator, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution, stated the following about the cache discovered in 1916 on the James Tyrrell farm northeast of Mackinaw: ‘Undoubtedly, they represent the most skillful work in stone flaking that has yet been found in this country.’ Thirty-five bifaces (a particular cut) from the Mackinaw cache are on exhibit at the Illinois State Museum in Springfield. Three are in McLean County Historical Society Museum in Bloomington, and one is owned by Mr. Stuart Ruch of Champaign. These are thought to be from the Hopewell culture (100 BC to AD 300). Irvin Wyss and Ivan Lindsey are two local men who were digging when they found the cache. Many artifacts have been found by others. Ernest Fuehring has a display in the Mackinaw Federal Savings and Loan Building.”

The most obvious marks of Mackinaw’s Indian cultural heritage are the village’s name and the name of the Mackinaw River. As a rule, the names of rivers and notable natural geographical features tend to be older than the names of towns or cities. Naturally that is the case with the village of Mackinaw. It may be a surprise to learn, however, that the village did not derive its name from the river.

According to “Mackinaw Remembers,” “It is an accepted fact [the village of Mackinaw] bears the name of Chief Mackinaw or Mackinac of the Kickapoo tribe . . . Some say Mackinaw means ‘little chief.’ It is listed in Illinois State History, No. 4, p. 57, 1963, by Virgil K. Vogel, pamphlet series of Illinois State Historical Society, as meaning turtle. It is taken from the language of the Ojibways.”

The river’s name, however, is an abbreviated form of “Michilimackinac,” a name which some people continued to use even as late as 1846. “In 1681 Father Marquette mentions the Michilimackinac River in his log. It is so-spelled on some maps published in 1822 in the Atlas of Indian Villages of Illinois, compiled by Tucker and Temple,” says “Mackinaw Remembers.”

“Mackinaw Remembers” also has this to say about the Native American peoples living in the area in the early 1800s: “The Indians left a definite mark in our area. War clouds just prior to the War of 1812 made feisty Kickapoos even more restless. They burned settlements on their move toward Lake Peoria. One band of them took up quarters with some Potawatomi, Chippewa, and Ottawa on the Mackinaw River. The peaceful Potawatomi far outnumbered the other tribes. Their chief was named Shimshack (sic – Shickshack). Chief Mackina of the Kickapoos eventually became friendly; however, he and the tribes left with the mass evacuation of Indians in Illinois in 1832.”

Chapman’s Tazewell County history also includes some anecdotes of Chief Mackinaw, or “Old Machina” as Chapman calls him, and notes that his people, the Kickapoo, “dwell in the western and southwestern part of the county” (page 195).

“For some years after the first settlers came wigwams were scattered here and there over the county . . . Another extensive camping ground was on the Mackinaw river, near the present town of Mackinaw. Old Machina was the chief of this band. The Kickapoos had made a treaty shortly previous to the coming of the first settler, by which the whites acquired all their land. When the whites came, however, to settle and occupy the land the Kickapoos were angry, and some of them felt disposed to insult and annoy the settlers. When John Hendrix came to Blooming Grove the Indians ordered him to leave. Not long afterwards they frightened away a family which settled on the Mackinaw. Old Machina ordered one family away by throwing leaves in the air. This was to let the bootanas (white men) know that they must not be found in the country when the leaves of autumn should fall. In 1823, when the Orendorffs came, Old Machina had learned to speak a little English. He came to Thomas Orendorff and with a majestic wave of his hand said: ‘Too much come back, white man: t’other side Sangamon’” (page 195-196).

Fanny Herndon, one of the “Snowbirds” (the survivors of “the Deep Snow” during the extremely harsh winter of 1830-31), “related stories of earlier settlers mentioning the many tepees here. She told of an Indian trail which came in the village [of Mackinaw] from the northeast, went past the west side of the Bryan Zehr place, and led to the present home of Clifford Rowell. It continued southwest along the bluffs.

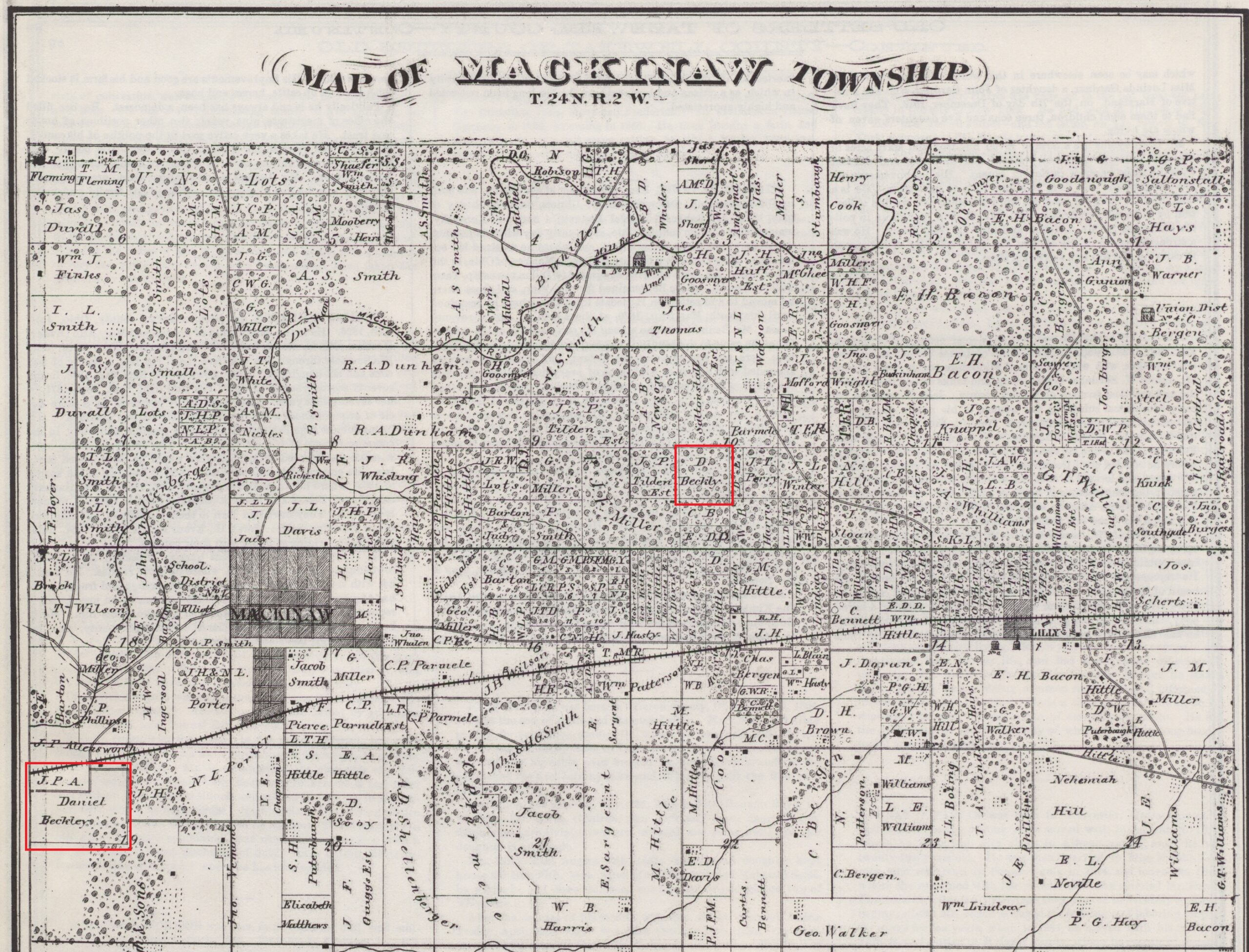

The formal founding of the village of Mackinaw is almost coeval with the establishment of Tazewell County in 1827. Originally when Illinois legislators made plans to form a new county out of Peoria County, the proposed name was Mackinaw County, not Tazewell County. In fact, the bill that was approved by the Illinois House of Representative in January 1827 was named, “An Act Creating Mackinaw County.” The Illinois Senate, however, amended the title to read, “An Act Creating Tazewell County,” and it was in that form that the bill passed the Senate on Jan. 31, 1827. Gideon Rupert of Pekin is credited with the choice to name the county after Rupert’s fellow Virginian Littleton Waller Tazewell, U.S. Senator from Virginia.

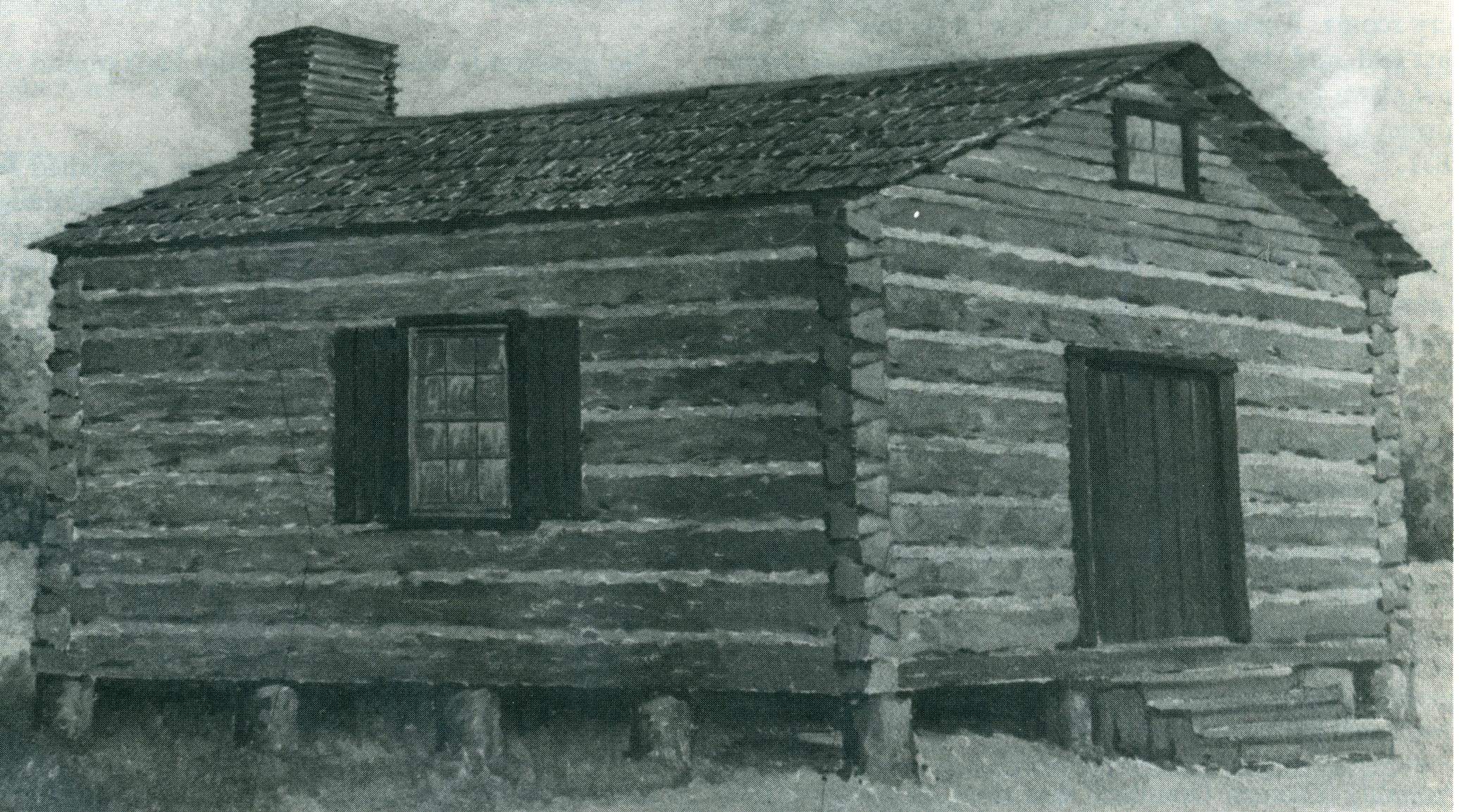

The legislation erecting Tazewell County also fixed the county seat at Mackinaw, which then was near the center of the county. William H. Hodges, County Surveyor, was hired to lay off the town of Mackinaw, and the sale of town lots was then advertised for three weeks in the Sangamon Spectator. It was decided that the county court house – a relatively simply log structure –was to be built “at or near the spot where the commissioners drove down a stake, standing nine paces in a northeastern direction from a white oak blazed on the northeastern side.” That was Lot 1, Block 11, where the Eddy Smith family lived in 1977. The Mackinaw courthouse served the county for only three years, from 1828 to 1831. Then followed the rivalry between Pekin and Tremont for the honor of county seat which this column has previous described.