This is a reprint of a “From the Local History Room” column that first appeared in Sept. 2014, before the launch of this weblog.

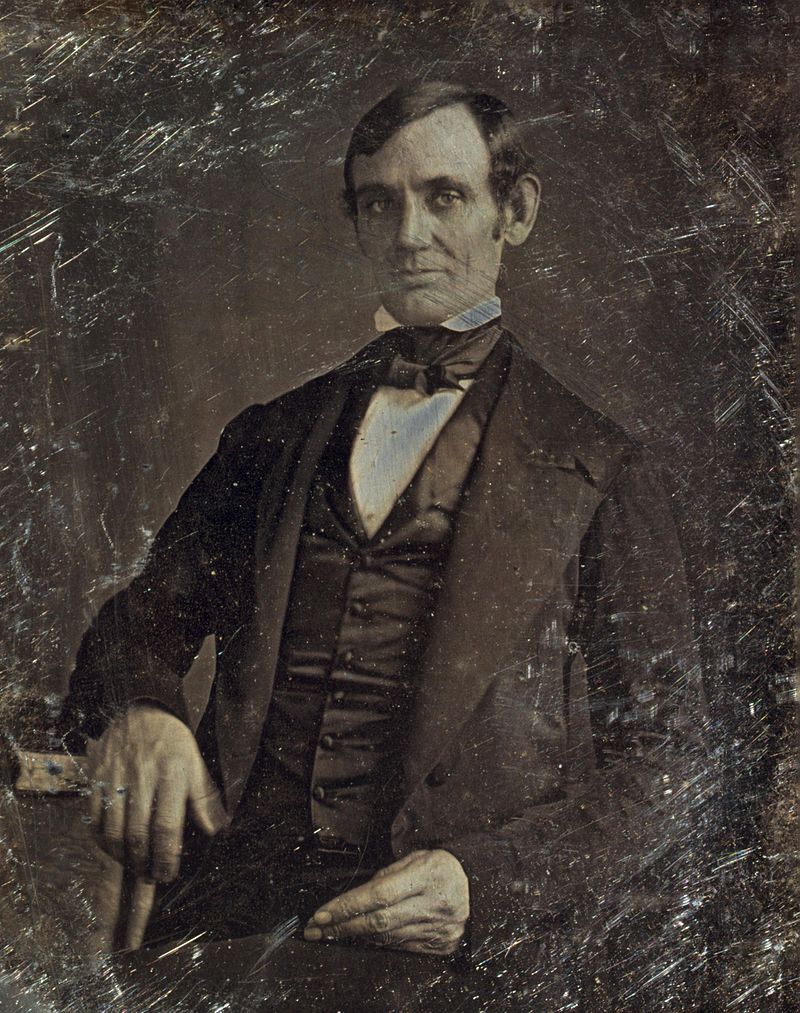

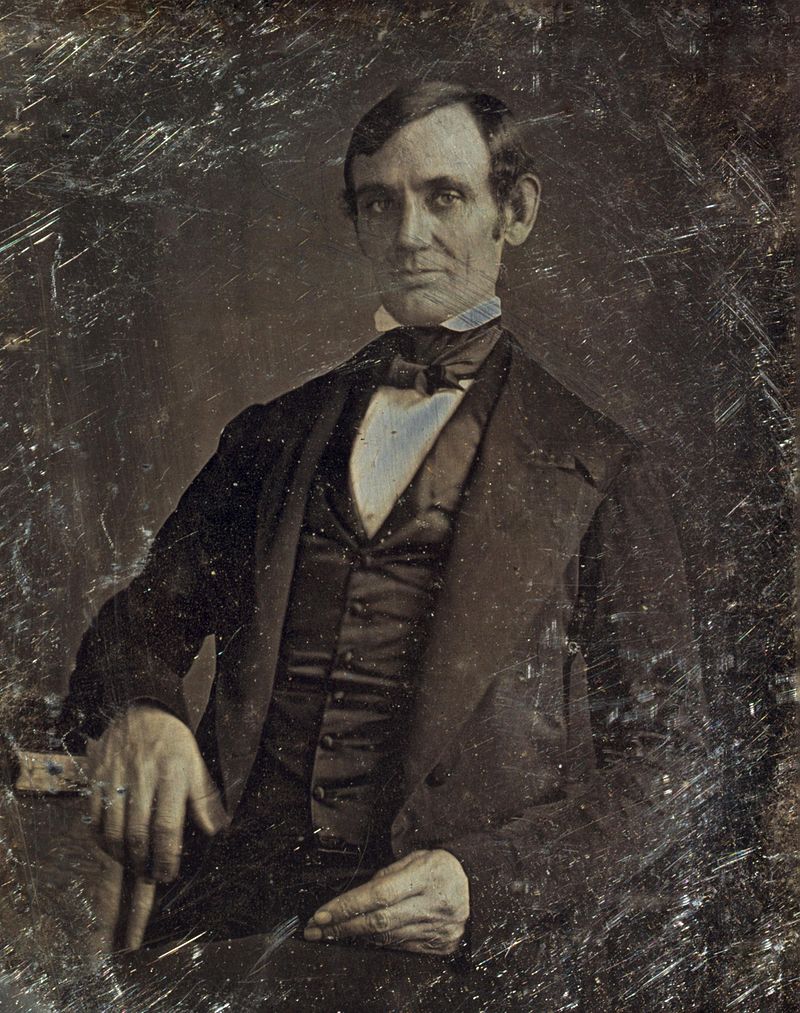

In a prior “From the History Room” column, we surveyed a list of local sites in Tazewell County that have direct and indirect links to President Abraham Lincoln. One of those sites was the former county courthouse in Tremont, where the county seat was located from 1836 to 1849. During those years, Lincoln’s work as an attorney often brought him to Tazewell County, and he would attend to his lawyerly duties at the courthouse in Tremont.

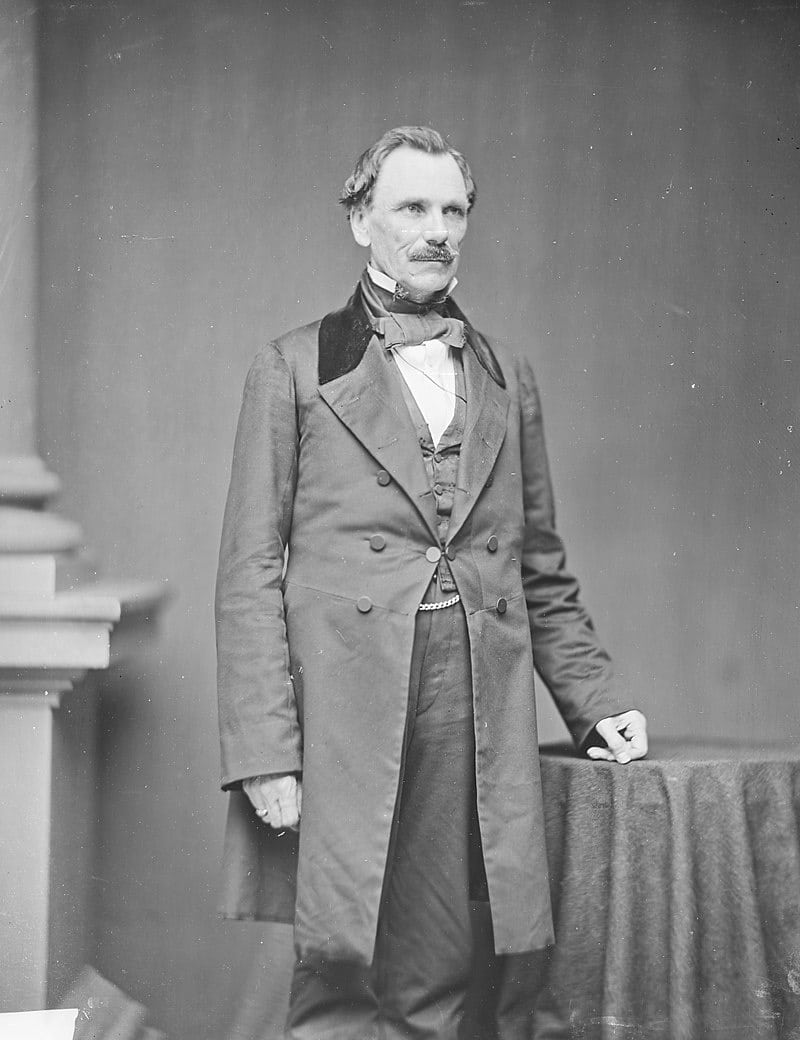

It was on one of those occasions in Tremont when Lincoln was challenged to a duel in 1842 by Gen. James Shields, auditor for the state of Illinois. A somewhat lengthy account of the duel – an incident of which Lincoln did not like to speak – is found in Charles C. Chapman’s 1879 “History of Tazewell County,” pages 146-148.

The occasion for Shields’ challenge of Lincoln was a crisis that led to the closing of the Illinois State Bank in August 1842, a decision that Shields, a Democrat, supported despite the great hardship it caused most Illinois residents. Lincoln, a Whig, chose to write a pseudonymous editorial decrying the banking crisis, singling out Shields for special mockery and personal insult. As Chapman says:

“During the period of the greatest indignation toward the State officials, under the nom de plume of ‘Rebecca,’ Abraham Lincoln had an article published in the Sangamo Journal, entitled ‘Lost Township.’ In this article, written in the form of a dialogue, the officers of the State were roughly handled, and especially Auditor Shields. The name of the author was demanded from the editor by Mr. Shields, who was very indignant over the manner in which he was treated. The name of Abraham Lincoln was given as the author. It is claimed by some of his biographers, however, that the article was prepared by a lady, and that when the name of the author was demanded, in a spirit of gallantry, Mr. Lincoln gave his name. In company with Gen. Whiteside, Gen. Shields pursued Lincoln to Tremont, Tazewell county, where he was in attendance upon the court, and immediately sent him a note ‘requiring a full, positive and absolute retraction of all offensive allusions’ made to him in relation to his ‘private character and standing as a man, or an apology for the insult conveyed.’ Lincoln had been forewarned, however, for William Butler and Dr. Merriman, of Springfield, had become acquainted with Shields’ intentions and by riding all night arrived at Tremont ahead of Shields and informed Lincoln what he might expect. Lincoln answered Shields’ note, refusing to offer any explanation, on the grounds that Shields’ note assumed the fact of his (Lincoln’s) authorship of the article, and not pointing out what the offensive part was, and accompanying the same with threats as to consequences, Mr. Shields answered this, disavowing all intention to menace; inquired if he was the author, asked a retraction of that portion relating to his private character. Mr. Lincoln, still technical, returned this note with the verbal statement ‘that there could be no further negotiations until the first note was withdrawn.’ At this Shields named Gen. Whiteside as his ‘friend,’ when Lincoln reported Dr. Merriman as his ‘friend.’ These gentlemen secretly pledged themselves to agree upon some amicable terms, and compel their principals to accept them. The four went to Springfield, when Lincoln left for Jacksonville, leaving the following instructions to guide his friend, Dr. Merriman:

“‘In case Whiteside shall signify a wish to adjust this affair without further difficulty, let him know that if the present papers be withdrawn and a note from Mr. Shields, asking to know if I am the author of the articles of which he complains, and asking that I shall make him gentlemanly satisfaction, if I am the author, and this without menace or dictation as to what that satisfaction shall be, a pledge is made that the following answer shall be given:

“‘I did write the “Lost Township” letter which appeared in the Journal of the 2d inst., but had no participation, in any form, in any other article alluding to you. I wrote that wholly for political effect. I had no intention of injuring your personal or private character or standing, as a man or gentleman; and I did not then think, and do not now think, that that article could produce or has produced that effect against you ; and, had I anticipated such an effect, would have foreborne to write it. And I will add that your conduct toward me, so far as I know, had always been gentlemanly, and that I had no personal pique against you, and no cause for any.

“‘If this should be done, I leave it to you to manage what shall and what shall not be published. If nothing like this is done, the preliminaries of the fight are to be:

“‘1st. Weapons. — Cavalry broad swords of the largest size, precisely equal in all respects, and such as are now used by the cavalry company at Jacksonville.

“‘2d. Position. — A plank ten feet long and from nine to twelve inches broad, to be firmly fixed on edge, on the ground, as a line between us which neither is to pass his foot over on forfeit of his life. Next a line drawn on the ground on either side of said plank, and parallel with it, each at the distance of the whole length of the sword, and three feet additional from the plank; and the passing of his own such line by either party during the fight, shall be deemed a surrender of the contest.

“‘3d. Time. — On Thursday evening at 5 o’clock, if you can get it so; but in no case to be at a greater distance of time than Friday evening at 5 o’clock.

“‘4th. Place. — Within three miles of Alton, on the opposite side of the river, the particular spot to be agreed on by you.

“‘Any preliminary details coming within the above rules, you are at liberty to make at your discretion, but you are in no case to swerve from these rules, or pass beyond their limits.’”

The reason Lincoln chose cavalry broad swords as the weapons for the duel is because Lincoln hoped to use his greater height and longer arms to his advantage against Shields. The duel was to take place in Missouri because dueling was still legal there.

So it was that on Sept. 22, 1842, Lincoln and Shields and their seconds met at the appointed place, Bloody Island in the Mississippi River at St. Louis, which got its name because it was a favorite place for duels. In his essay, “Abraham Lincoln’s Duel – Broadswords and Banks,” Kelsey Johnston writes, “As the two men faced each other, with a plank between them that neither was allowed to cross, Lincoln swung his sword high above Shields to cut through a nearby tree branch. This act demonstrated the immensity of Lincoln’s reach and strength and was enough to show Shields that he was at a fatal disadvantage. With the encouragement of bystanders, the two men called a truce.”

Mutual friends of Lincoln and Shields then urged the two men to settle their disagreement peacefully, and Lincoln issued the public apology and retraction that Shields had requested. Years later, during the Civil War, Shields handed Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson his only defeat at the Battle of Kernstown in March 1862. In acknowledgement of Shields’ valor, Lincoln nominated him for promotion to the rank of Major General.