Only 11 months after the founding of Pekin, the survival of the nascent pioneer town was severely tested by a natural disaster that affected the whole of Central Illinois — the most brutal winter ever to hit Tazewell County, whose survivors afterwards were known as “Snowbirds.”

Today the term “snowbird” can be a slang term for U.S. retirees from northern states who own a second home or condominium in places like Florida or Arizona, where they live during the winter months, returning north with the return of warm weather in the spring. Tazewell County’s 19th century “Snowbirds” didn’t have that luxury but may have wished they did.

As “Pekin: A Pictorial History” (2004) explains, the Snowbirds of Tazewell County were “survivors of the deep snow that fell over Tazewell County in late December 1830, leaving drifts as high as 20 feet in some places. It snowed 19 times from December 29, 1830 to February 13, 1831. It was told that after the spring melt one could walk for a quarter acre stepping on the bones of the deer that perished.”

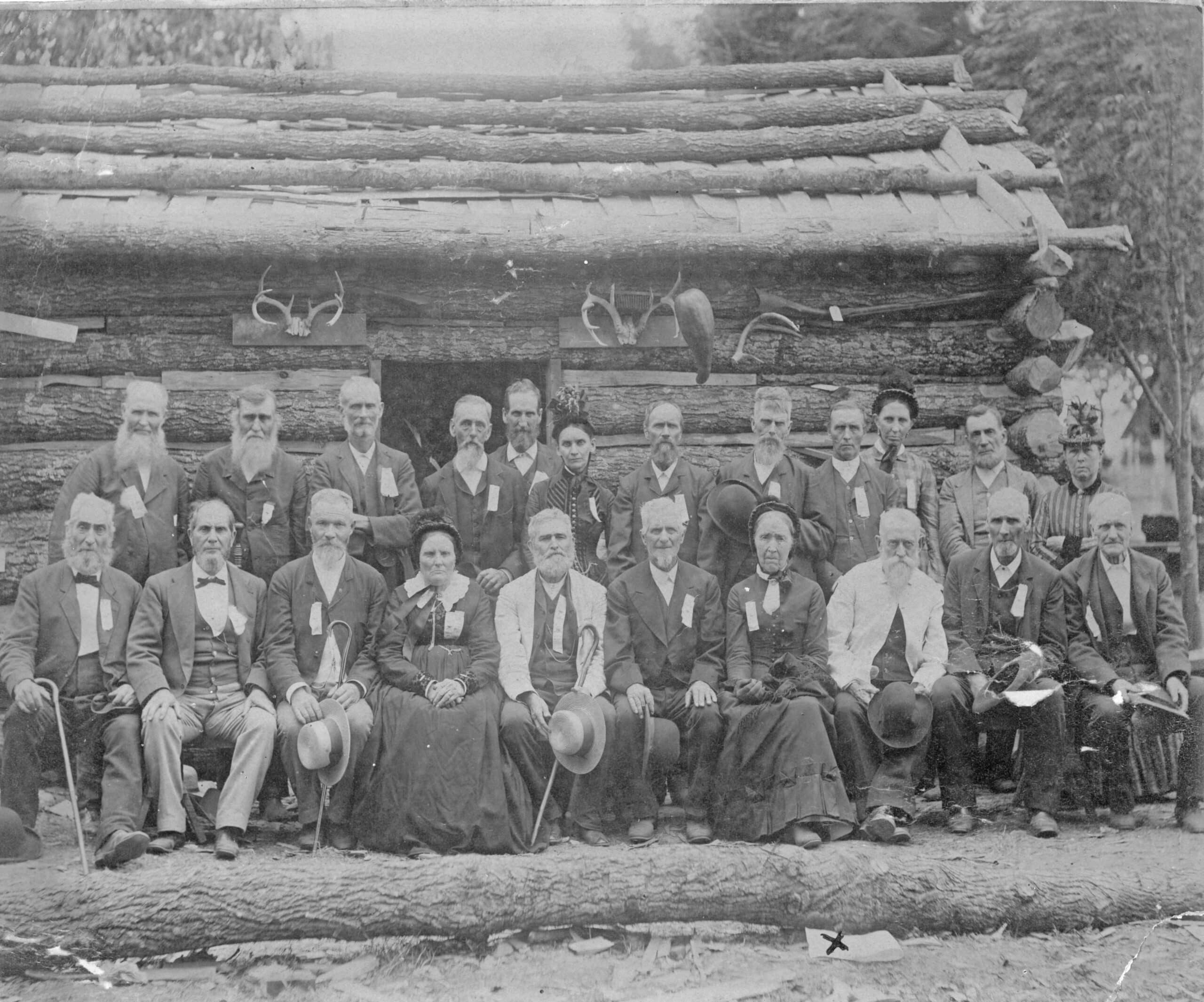

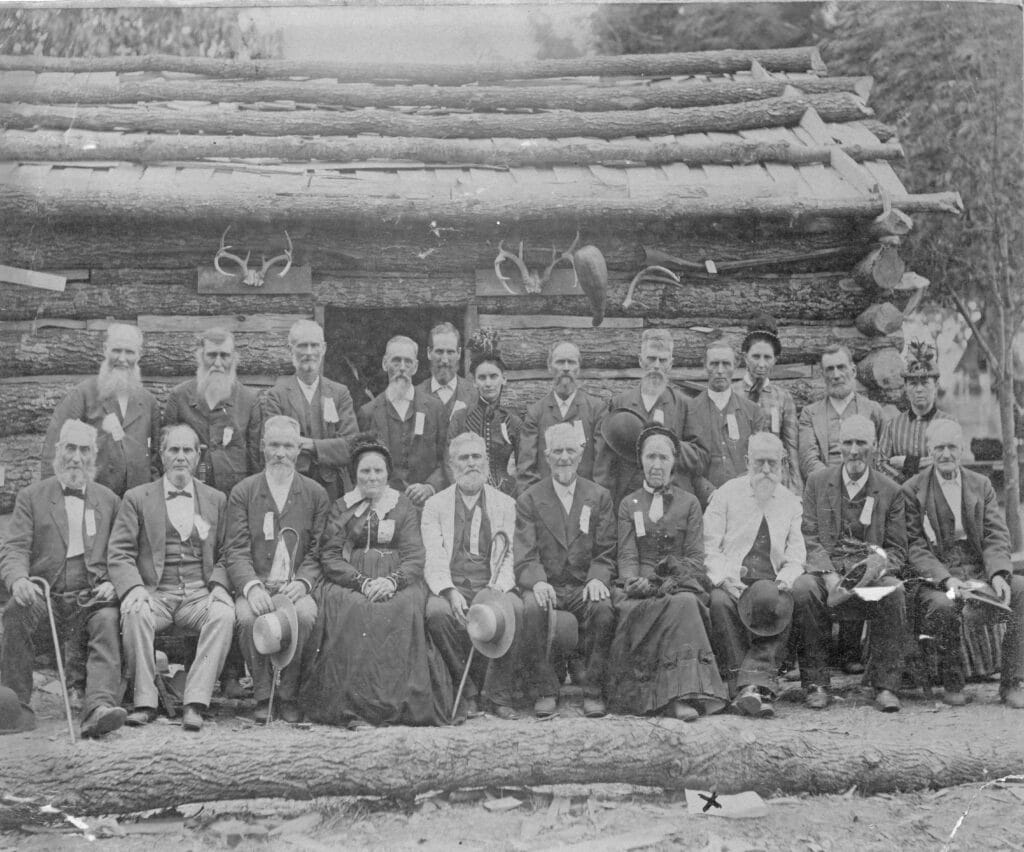

About 50 years after that unusually harsh winter, the county’s Snowbirds who were still alive — among whom were James Haines and Margaret Wilson Young — got together for a group photograph at the Tazewell County Fair in Delavan. That photo was reproduced in “Pekin: A Pictorial History” and again was included this year in the new Pekin Bicentennial Pictorial.

Pekin’s pioneer historian William H. Bates has more to say about that winter in his “Souvenir of early and notable events in the history of the North West territory, Illinois, and Tazewell County,” which Bates published in commemoration of the 21 June 1916 dedication of the new Tazewell County Courthouse.

On page 12 of his “Souvenir,” Bates wrote:

“The deep snow of 1830-31, was not only a record breaker, but established a record: Snow began falling December 29th, 1830, and continued for three days and nights, leaving the earth covered with a white mantle about four feet thick, with some drifts at least twenty feet deep. Many cattle and hogs, also all kinds of wild game, met death by freezing. The early settlers suffered many privations through hunger and cold. Between December 29, 1830, and February 13, 1831, snow fell nineteen times. The sun was seldom seen and a general gloom pervaded the settlements. Corn that had been left on the stalk in the field had to be gathered by digging in the snow for it. Many of the brave settlers had to travel on snow-shoes to the more favored places, to secure food and necessaries to save their families from starving. They stood on the crust of the frozen snow, and for fuel, cut off trees so high that after the snow had melted away some time in April, 1831, the stumps left above ground were tall enough for fence rails.”

That extreme winter weather apparently was part of a generally cooling trend at the time, because further on Bates commented, “There was frost during every month of 1831, consequently poor crops followed the efforts of the pioneer husbandman.”

The county had another bout of crazy winter weather just five years later. On page 14, Bates shared this recollection:

“’What a sudden change!’ is an expression often heard — but later years have not produced one equal to that of January, 1836: Snow had fallen to the depth of four inches, which was followed by a drizzling rain, leaving the earth covered with ‘slush’. A cold wave came from the northwest, and so sudden was the change that cattle, hogs, chickens, etc., froze fast where they were standing and had to be cut loose. Men and women, out in the fields and gardens, and short distances from their homes, nearly froze to death before they could seek covered protection, owing to the bitter cold.”