When French missionaries and explorers first came to the Illinois Country in the 1600s, they encountered the group of 12 or 13 Algonquin-speaking Native American tribes who are most commonly known today as the Illiniwek or Illini, and the French gave their land the name “Pays de Illinois” – the Country of the Illini, or the Illinois Country.

The Illiniwek first appear in the written record in 1640, when French Jesuit missionary Father Paul LeJeune listed a people called the “Eriniouai” who were neighbors of the Winnebago. Then in 1656, another Jesuit missionary, Father Jean de Quen, mentions the same people by the name of “Liniouek,” and in the following year Father Gabriel Druillettes called them “Aliniouek.” About a decade later, Father Claude Allouez told of his meeting some “Iliniouek.” In the 1800s, American writers began to adapt the spelling of the name to “Illiniwek.”

The French missionaries also noted in their American Indian language dictionaries that the Illiniwek’s own name for themselves was Inoka, a word of unknown meaning and derivation. According to the historical records of the French missionaries, however, the ethnic designation “Illinois” meant “the men.” The 1674 journal of Father Jacques Marquette’s first voyage says, “When one speaks the word ‘Illinois,’ it is as if one said in their language, ‘the men,’ – As if the other Indians were looked upon by them merely as animals.”

About two decades later, Father Louis Hennepin observed, “The Lake of the Illinois signifies in the language of these Barbarians, the Lake of the Men. The word Illinois signifies a grown man, who is in the prime of his age and vigor . . . The etymology of this word ‘Illinois’ derives, according to what we have said, from the term Illini, which in the language of this Nation signifies a man who is grown or mature.”

That is all that historical sources have to say about the meaning of “Illinois.” More recently, linguistic scholars of the vanished Algonquin dialects have speculated that “Illiniwek” may in fact have derived from a Miami-Algonquin term that means “one who speaks the normal way,” and that the French throughout the 1600s and 1700s misunderstood the name that the Inoka’s Algonquin-speaking neighbors gave them as their own name.

Be that as it may, it is thought that when the French first encountered the Illiniwek tribes, there were perhaps as many as 10,000 of them living in a vast area stretching from Lake Michigan out to the heart of Iowa and as far south as Arkansas. In the 1670s, the French found a village of Kaskaskias in the Illinois River valley near the present town of Utica, a village of Peorias near modern Keokuk, Iowa, and a village of Michigameas in northeast Arkansas.

The Kaskaskia village near Utica, also known as the Grand Village of the Illinois, was the largest and best known village of the Illinois tribes. A French Catholic mission, called the Mission of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin, and a fur trading post were set up there in 1675, causing the village population to swell to about 6,000 people in about 460 houses. It was not long, though, before European diseases and the ongoing Beaver Wars, which we recalled previously in this column, brought suffering and tragedy to the Illiniwek, causing their population size to plummet over the coming decades.

In the early 1690s, the expansionist wars of the Iroquois League of New York, which sought to control the fur trade, forced the Kaskaskias and other Illiniwek to abandon the Grand Village and move further south to the areas of the present sites of Peoria, Cahokia, and Kaskaskia. At the height of Iroquois power, the League was able to extend its reach as far as the Mississippi and most Illiniwek fled from Illinois to escape, while some Illiniwek groups accompanied the Iroquois and fought as their allies against their enemies. The Iroquois did not have enough people to hold the Illinois Country, however, and before long the Illiniwek were able to reclaim their old lands. Other tribes also found it necessary or advantageous to move into the Illinois Country during this period and soon after, however, such as the Pottawatomi, Kickapoo, Ottawa, and Piankeshaw.

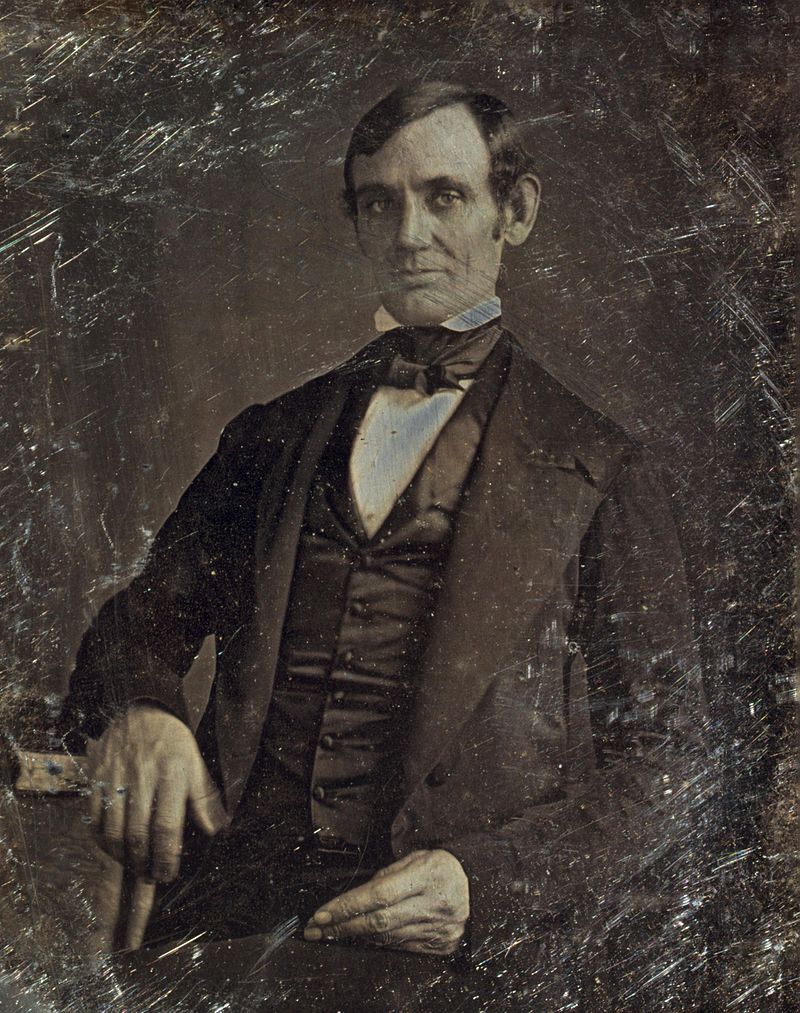

In the early decades of the 1700s, the Illiniwek became involved in a feud with the Meskwaki (Fox), during the series of battles between the French and the Meskwaki known as the Fox Wars. In 1722, the Meskwaki attacked the Illiniwek in retaliation for the killing of the nephew of Oushala, one of the Meskwaki chiefs. The Illiniwek were forced to seek refuge on Starved Rock, and they sent a messenger southwest to Fort de Chartres asking their French allies to rescue them, but by the time the French leader Boisbriand and his men had arrived, the Meskwaki had retreated, having killed 120 of the Illini. Four years later, the Marquis de Beauharnois, Governor of New France, organized an attack on the Meskwaki in Illinois in which 500 Illini warriors agreed to take part, but the Meskwaki escaped. The feud between the Illini and the Meskwaki culminated in early September 1730, when the Meskwaki were all but annihilated by an allied force of French, Illini, Sauk, Pottawatomi, Kickapoo, Mascouten, Miami, Ouiatenon, and Piankeshaw warriors.

By the middle of the 1700s, the original 12 or 13 Illiniwek tribes had been reduced by the wars and diseases of the 17th and 18th centuries to only five: the Cahokia, the Kaskaskia, the Michigamea, the Peoria, and the Tamaroa. According to legend, the Illiniwek suffered their most grievous defeat after the French and Indian War, when the great Ottawa chief Pontiac (Obwandiyag) was killed by Kinebo, a Peoria chief, in Cahokia on April 20, 1769. In revenge, the Ottawa and Pottawatomi banded together in a war of extermination against the Illini of the Illinois River valley, a large number of whom again sought refuge on Starved Rock. The Ottawa and Pottawatomi are said to have besieged the Illini on Starved Rock, where most of the Illini died of starvation (hence the name Starved Rock).

There is no contemporary record to substantiate that the Battle of Starved Rock, as it has been called, ever really took place. However, an elderly Pottawatomi chief named Meachelle, said to have been present at the siege as a boy, told his story to J. D. Caton in 1833, while an early white settler in the area, named Simon Crosiar, is said to have reported that Starved Rock was covered with the skeletal remains of the Illini in the years after the siege.

Whether or not that is really how the Illiniwek met their end, their numbers did drastically decline throughout the 1700s. By the early 1800s, only the Kaskaskia and Peoria tribes remained, about 200 people living in an area of southwestern Illinois and eastern Missouri near the Mississippi. In 1818, the Peoria, then in Missouri, ceded their Illinois lands, and in 1832 they ceded their Missouri lands and moved to Kansas. The descendants of the Illiniwek are today known as the Peoria Tribe of Indians, with their reservation in Ottawa County, Oklahoma.