In an essay entitled, “The Educational Value of ‘News,’” published in the Dec. 5, 1905, edition of The State of Columbia, S.C., George Helgesen Fitch wrote, “The newspapers are making morning after morning the rough draft of history. Later, the historian will come, take down the old files, and transform the crude but sincere and accurate annals of editors and reporters into history, into literature. The modern school must study the daily newspaper.”

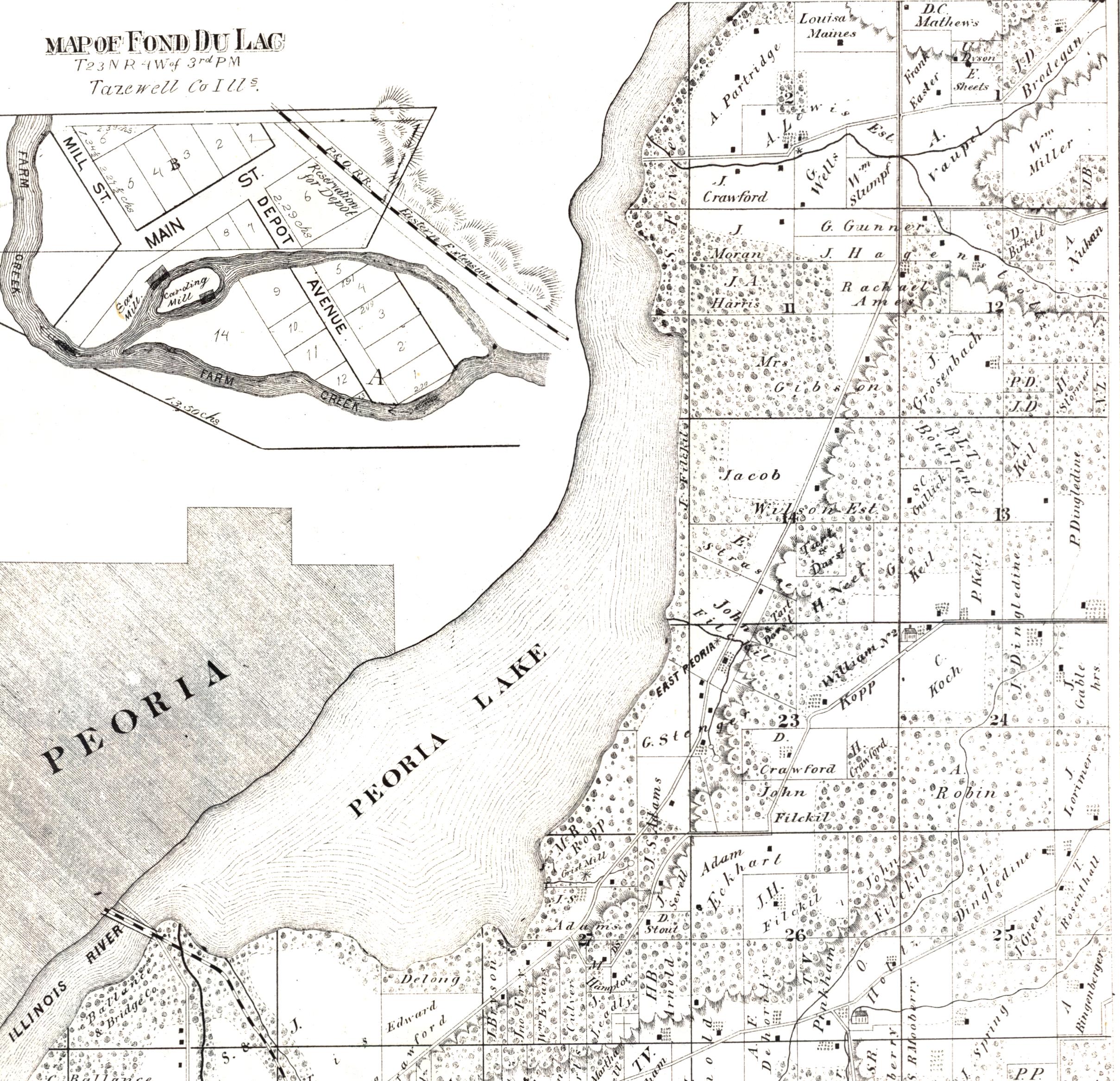

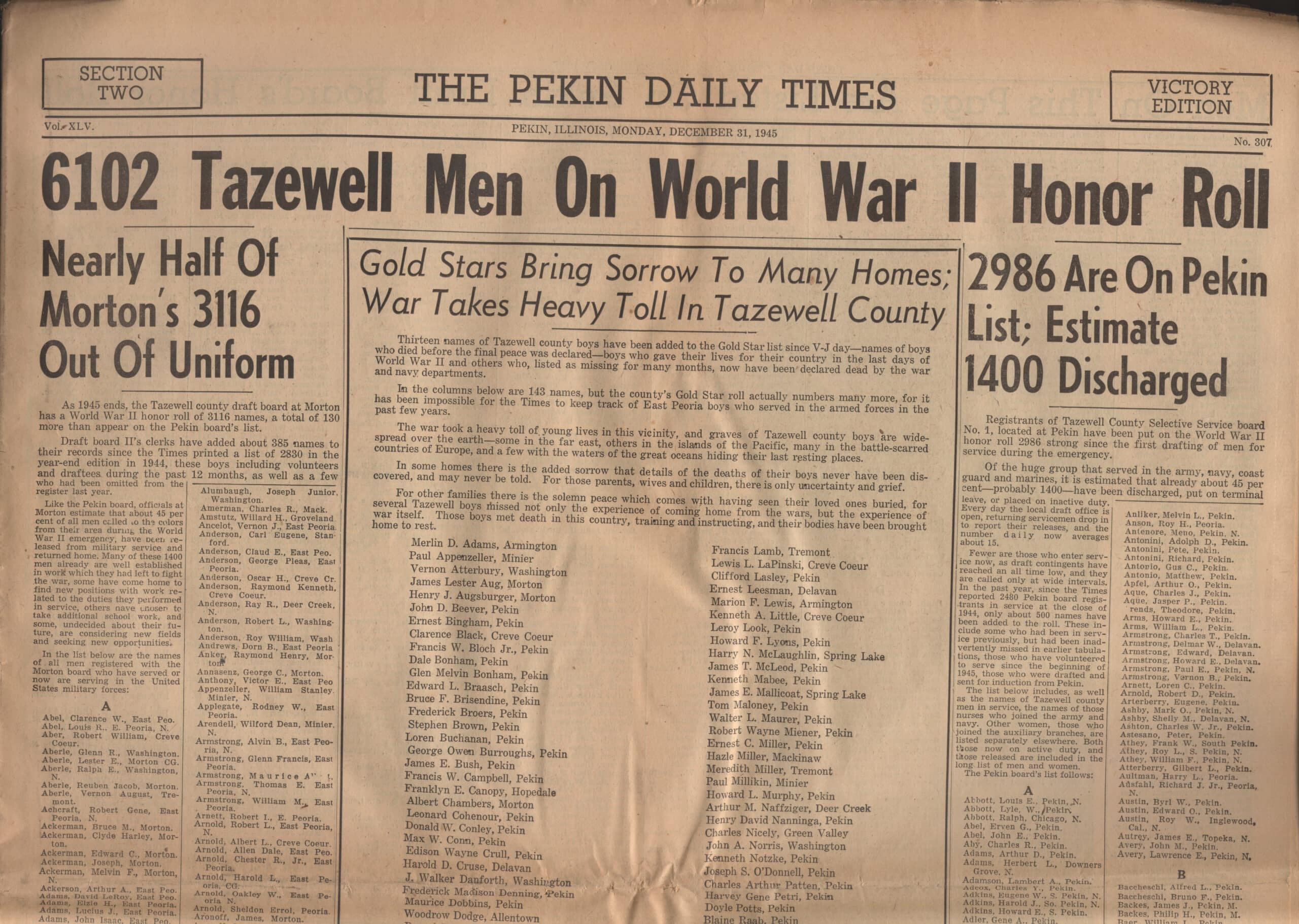

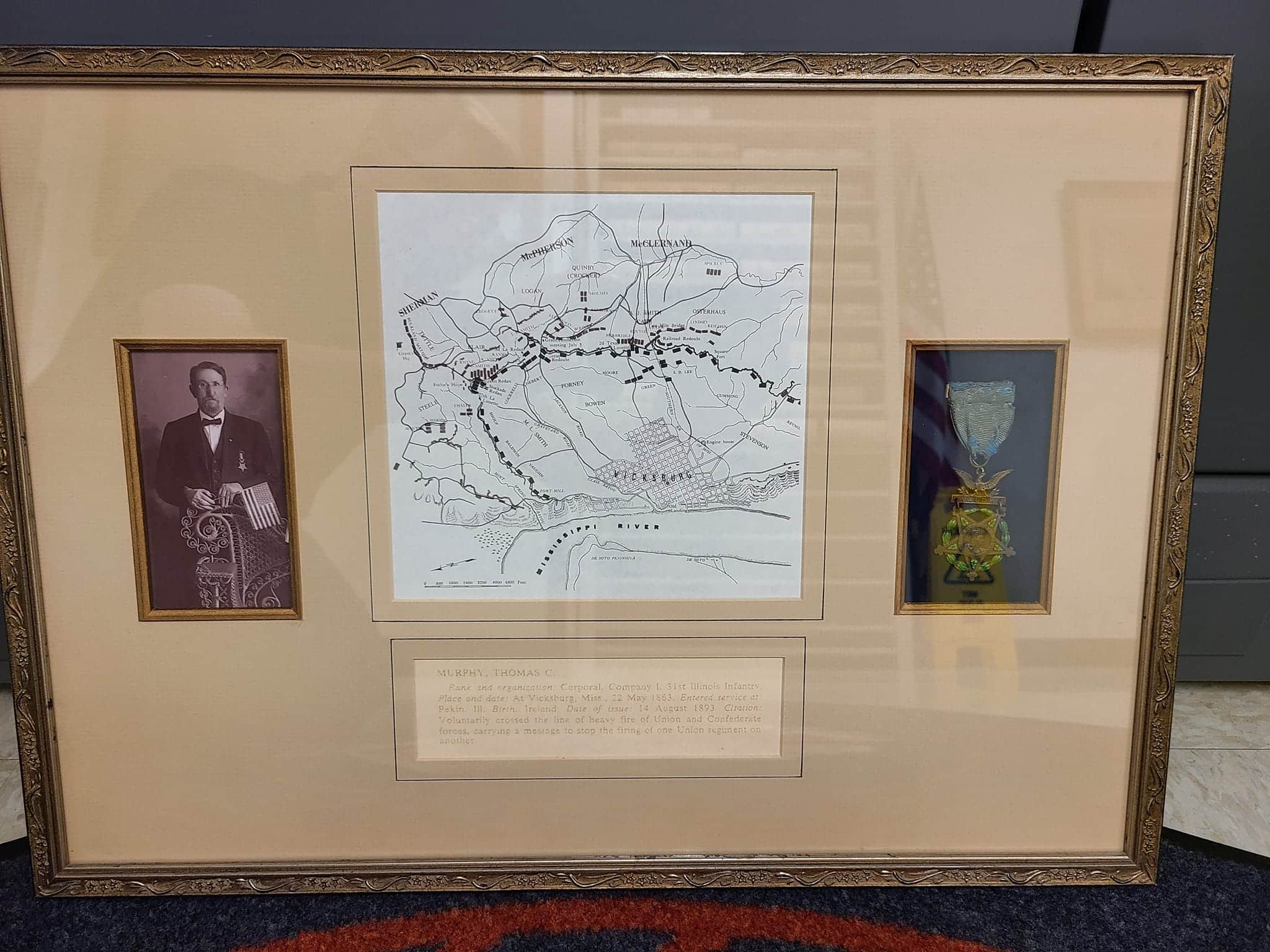

For those who would like to study the Civil War’s “rough draft of history,” a very useful resource is “The Civil War Extra – From the Pages of The Charleston Mercury & The New York Times” (1975, Arno Press, New York), edited by Eugene P. Moehring and Arleen Keylin. A copy of Moehring and Keylin’s tome recently was added to the Pekin Public Library’s Local History Room collection.

“The Civil War Extra” is a compilation of facsimile reprints of the front pages of the Pro-Union New York Times and the Pro-Confederacy Charleston (S.C.) Mercury, beginning with The New York Times issue of Jan. 16, 1861 (on page 4), and the 13 April 1861 issue of The Charleston Mercury, and carrying the newspapers’ account of the tragic conflict up to the Feb. 11, 1865, edition of The Charleston Mercury (on page 287) and the April 18, 1865, edition of The New York Times (page 309). Moehring and Keylin also selected various Civil War-era photographs, drawings, lithographs, and engravings to illustrate the pages of “The Civil War Extra.”

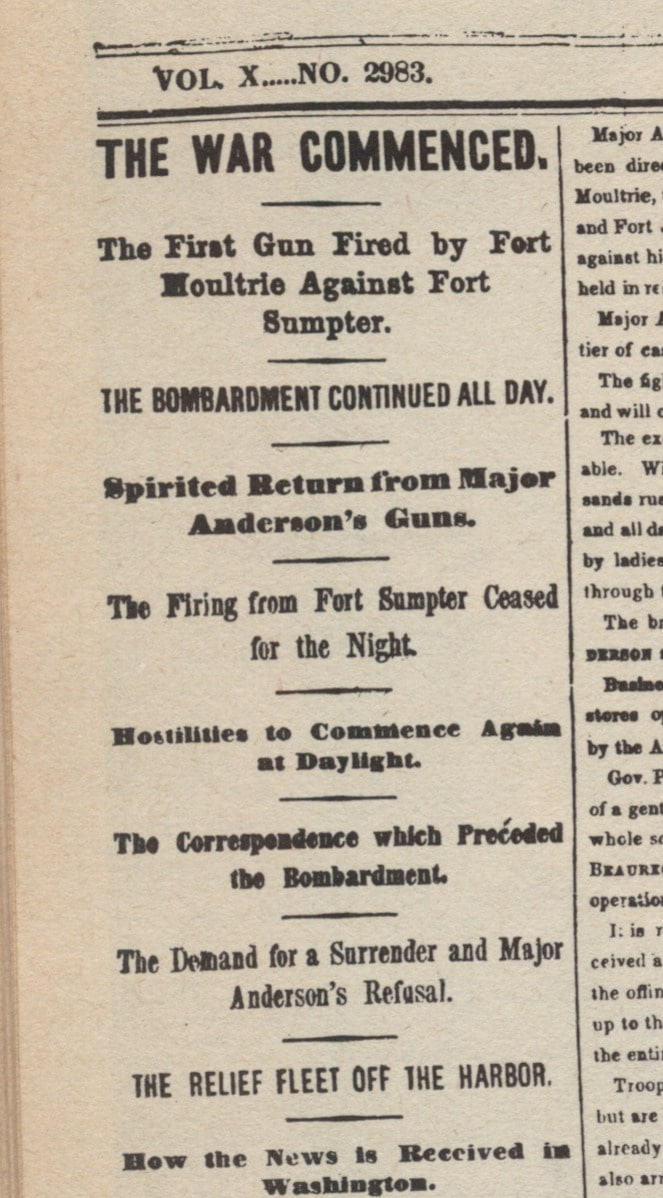

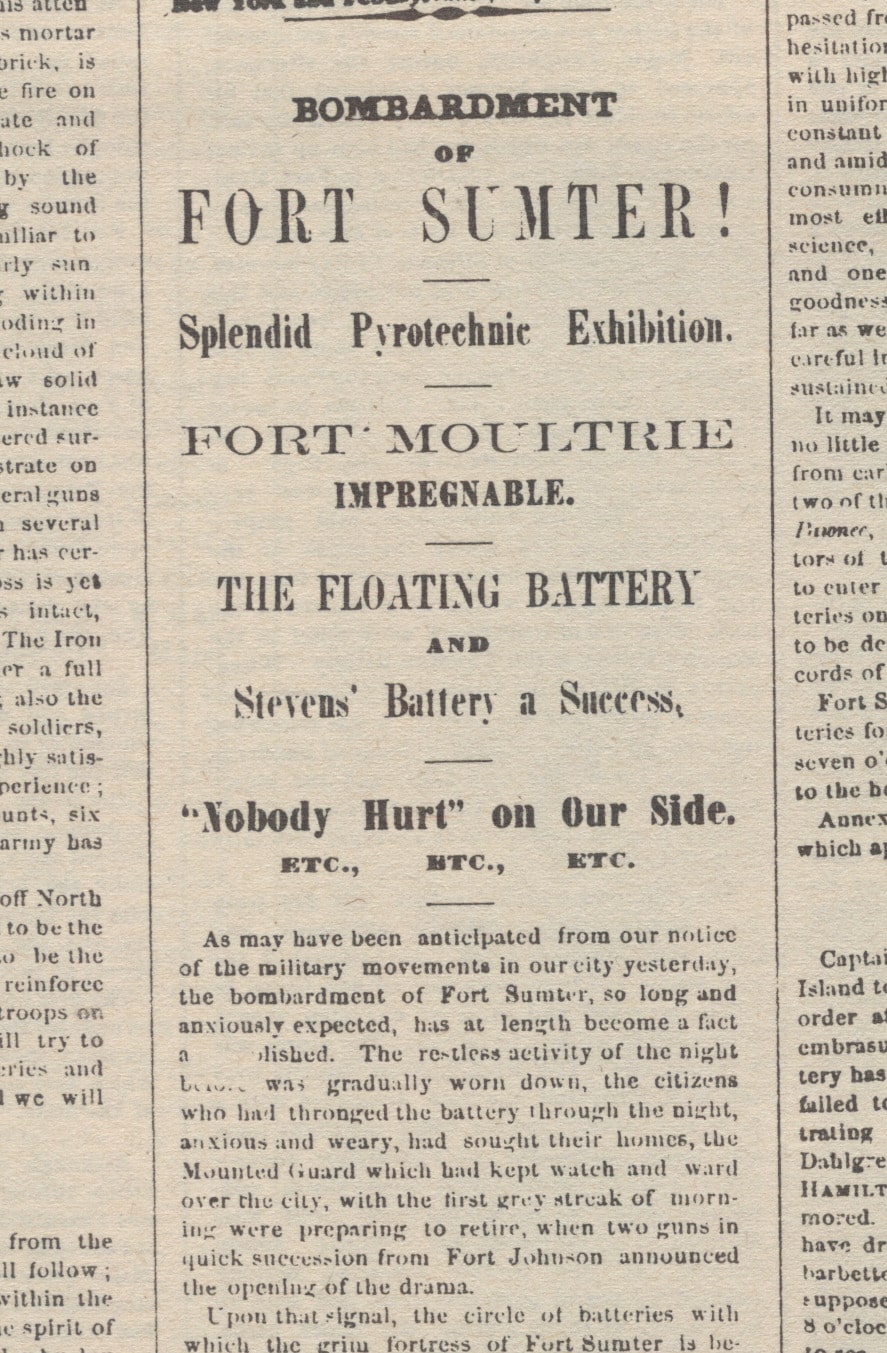

Then as now, newspapers published stories and editorial essays that were colored by spoken and unspoken political biases. The advantage of a compilation of issues from leading Northern and Southern newspapers is that the reader can examine news reports of major Civil War events from both sides of the conflict. The difference in perspective is evident from the first reports of the bombardment of the Union’s Fort Sumter by Confederate forces. Where The New York Times announced, “THE WAR COMMENCED – The First Gun Fired by Fort Moultrie Against Fort Sumpter” (sic), making sure to mention the “Spirited Return from Major Anderson’s Guns,” for its part The Charleston Mercury heralded the “BOMBARDMENT OF FORT SUMTER! – Splendid Pyrotechnic Exhibition,” adding the boasts, “FORT MOULTRIE IMPREGNABLE” and “‘Nobody Hurt’ on Our Side.”

The war dragged on over the next four years, claiming 600,000 casualties – among them United States President Abraham Lincoln, felled by a Confederate assassin’s bullet. The Charleston Mercury continued to publish throughout the war until, the tide having turned decisively in favor of the Union, the Confederate forces in South Carolina were vanquished. In its final three issues, The Charleston Mercury reprinted the desperate but futile call-to-arms of South Carolina Governor A. G. Magrath: “The doubt has been dispelled. The truth is made manifest, and the startling conviction is now forced upon all. The invasion of the State has been commenced; . . . I call now upon the people of South Carolina to rise up and defend, at once, their own rights and the honor of their State . . .”

From that point “The Civil War Extra” carries on the story from the perspective of The New York Times, through the surrender of the Confederate forces up to the announcement of Lincoln’s assassination by John Wilkes Booth in the edition of Sunday, April 16, 1865 – “OUR GREAT LOSS – Death of President Lincoln. – The Songs of Victory Drowned in Sorrow.” The final front page tells of the capture of Mobile, Ala., by Union forces, and the manhunt for Lincoln’s assassin and Booth’s co-conspirators. The book concludes with a drawing of President Lincoln’s funeral procession in Washington, D.C.