This is a reprint of a “From the Local History Room” column that first appeared in January 2015, before the launch of this weblog.

The adventures of Joel Hodgson

By Jared Olar

Local History Specialist

Coming to Tazewell County with the first wave of white settlers during the 1820s and 1830s was a resident of Ohio named Joel Hodgson.

A relative of the Tazewell County pioneer family the Dillons, Hodgson first visited what would become Tazewell County in the autumn of 1821 as an advance scout for a proposed “colony” or settlement of Ohio residents. Nothing came of those plans, but Hodgson returned on his own account in 1828 with the intention of settling in Tazewell County permanently. Several of his Hodgson relatives also came to Tazewell during those years.

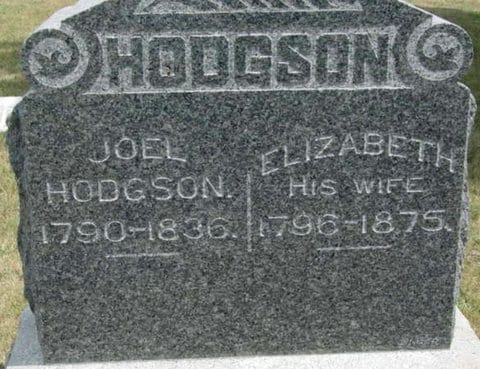

Joel Hodgson, born Nov. 17, 1789 in Guilford County, North Carolina, was a son of Thomas Hodgson and Patience Dillon. He married Elizabeth Castor (1796-1875) and had several children, including sons Eli and James, and a daughter named Malinda who married Aaron Dillon. An account of his adventures, written in 1885 by Eli Hodgson and Zimri Hodgson of Ottawa, was included in Ben C. Allensworth’s 1905 “History of Tazewell County,” on pages 701-703. Here are excerpts from that account:

“In 1831 Joel Hodgson emigrated from Clinton County, Ohio, to Tazewell County, Illinois, bringing with him a quantity of timothy, clover and blue-grass seeds. After subduing the wild sods of the prairie he sowed a few acres with his favorite grass seed, which is supposed to be the first importation of these grasses to this country. . .

“At the same time Joel Hodgson brought about a bushel of one kind of the choicest peach seeds, which he generously distributed among his widely scattered neighbors who would plant and cultivate. The soil and climate proved to be congenial for raising this palatable fruit, which was true to its kind, and for a number of years bountiful crops of peaches were the result.

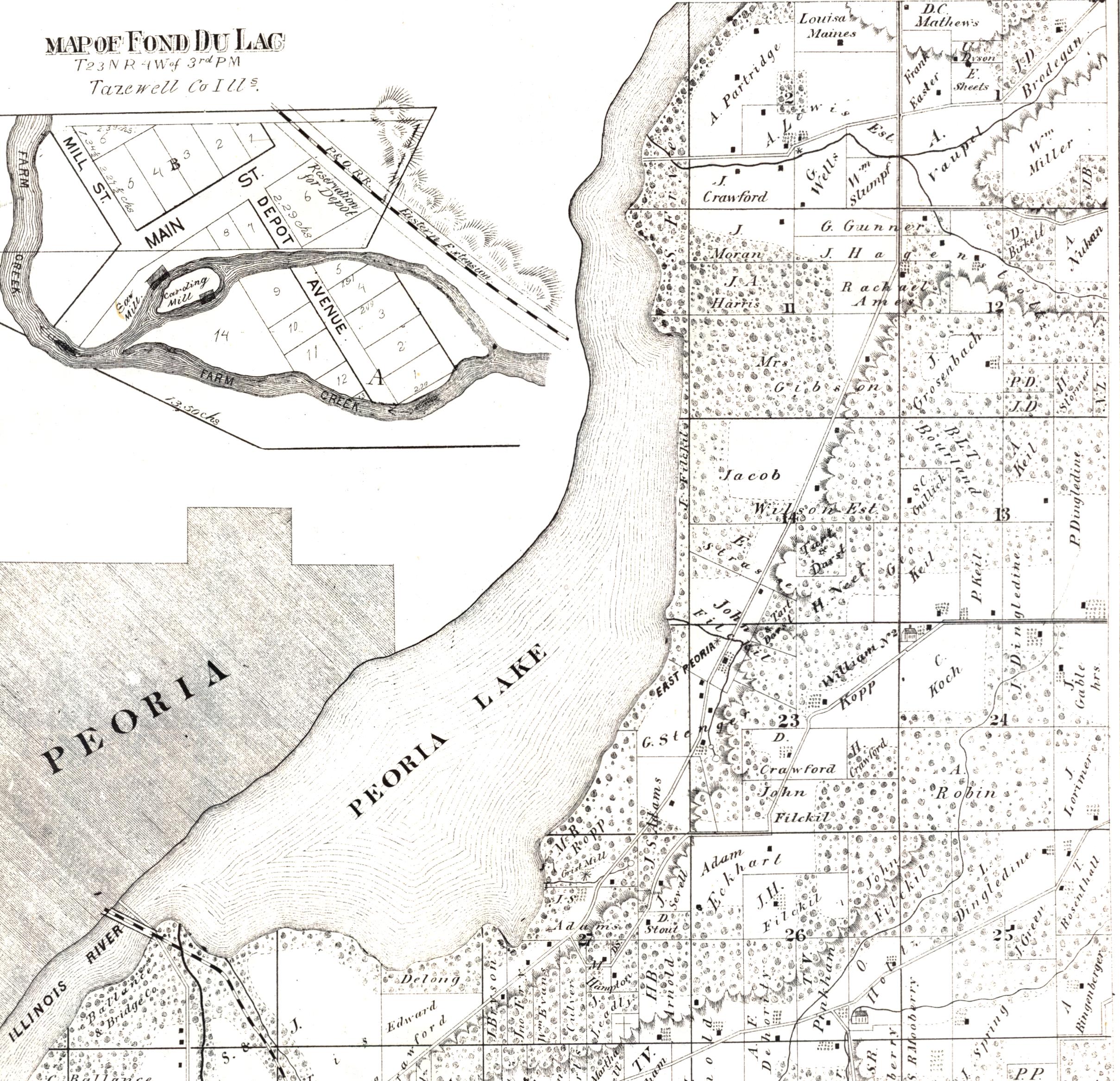

“Previous to this, in the autumn of 1821, a number of families of Clinton County, Ohio, proposed to emigrate to some western location, in sufficient numbers to support a school, church, etc., and deputed Joel Hodgson and Luke Dillon to explore the then wild and unoccupied Northwest, and select a location for the colony. His colleague having been taken sick, Mr. Hodgson resolutely started alone on horseback. He equipped himself with a good horse, saddle and bridle, a packing wapello well fitted with dried beef, crackers and hardtack. His other equipments were the best map he could then get of the western territories, a pocket compass, flint, steel and punk-wood with which to kindle a fire, as matches were not then known. He carried no weapon, often remarking that an honest face was the best weapon among civilized or savage man. After crossing the state of Indiana, then a wilderness, he entered Illinois where Danville now is, and here found a small settlement and some friends. Here he made a short stay, then took a northwest course to reach the Illinois river, his map and compass his only guide. He put up usually where night found him. Striking a fire with his flint, steel and punk, wrapped in his blanket, and with the broad earth for a bed, he reposed for the night. He stated that his horse became very cowardly, so that he would scarcely crop the grass which was his only sustenance; he would keep close by his master, following him wherever he went, sleeping at night by his side, and would not leave him at any time. With no roads but an occasional Indian trail, through high grass and bushes, over the broad limitless prairie, or along the timber belts, casually meeting a party of Indians, with whom he conversed only by signs, it is not surprising that horse and rider should be lonely, suspicious and fearful. The Indians were friendly, offering to pilot him wherever he wished to go, but were importunate for tobacco and whiskey; in vain, however, for he carried neither. He reached the Illinois river, he supposed, just below the mouth of the Kankakee, and followed down on the south side till he reached the mouth of the Fox River, and recognized it on his map, the first time he had been certain of his locality since he left Danville. He explored each of the southern branches of the Illinois for several miles from their mouths, passing up one side and down the other. He thus explored the country to Dillon’s Grove, in Tazewell county, near Fort Clark (Peoria). There, as he expected, he met a few settlers, old neighbors of his from Ohio, the first white men he had seen since leaving Danville. He then returned by way of Springfield and Vandalia, to Danville, where he made a claim on government land which he afterwards purchased. He returned to Ohio and reported that he found no suitable location for the proposed colony west of Danville.

“Some might think it rather singular that a man of his resolution and sound judgment should pass through the best part of the State of Illinois, the best portion of the West, and as good a country as the sun shines on, and then make such a report. But those who saw it as he saw it can properly appreciate his decision; and the fact that he made such difference between then and now. Surrounded by the solitude which even his horse felt so keenly, he was not in a mood to take in the full value of a prairie farm, and the wild region was not then understood. There was supposed to be an almost fatal deficiency of timber, and the coal-fields were hidden in the bowels of the earth. The prairie was supposed to be so cold and bleak in winter as to be uninhabitable, and that not more than one-tenth of the country could ever be utilized. . . . There was no civilization here. The deer, the wolf and the Indian held a divided empire, and, to the solitary traveler, it seemed that generations must pass before this immense solitude could be made coeval with the converse and business of a civilized people . . . .

“Our explorer eventually changed his opinion, for, in 1828, he purchased a farm in Tazewell county, and removed there three years later, having in the autumn of 1828 taken a trip through the country similar to that in 1821, when some few settlements and more experience softened the aspects of the then changing wilderness, and convinced him of the feasibility of settling the prairie region. His colleague, Luke Dillon, with a number of their friends, emigrated to Vermillion county, Illinois, and settled near Danville, and Mr. Hodgson himself designed settling on his purchase of the same place, but the milk-sick disease broke out among cattle on his lands, causing him to change his mind, as above stated. He remained on his purchase, near Pekin, until his death in the autumn of 1836, leaving a widow and nine children, of whom four sons and one daughter yet survive. Similar adventures were made by other parties, cousins of Joel Hodgson, about the same time, and under much same trying circumstances.”

Joel Hodgson died in or near Pekin on Oct. 25, 1836, and was buried in Dillon Cemetery. That autumn was one of grief for the Hodgsons, for Joel’s daughter Malinda also died in 1836 just 10 days after her husband Aaron and five days before her father.