This is a revised version of a “From the Local History Room” column that first appeared in February 2012 before the launch of this weblog, republished here as a part of our Illinois Bicentennial Series on early Illinois history.

On Friday, Aug. 3, at 11 a.m., in the Pekin Public Library Community Room, the library will have a showing of two videos about Pekin’s first astronaut Lt. Commander (ret.) Scott Altman. The videos are a part of the library’s Illinois Bicentennial Series.

First will be a 35-minute video of Altman’s keynote address at an April 1996 meeting of the Pekin Area Chamber of Commerce. Afterwards will be a showing of the footage of Altman’s recent induction into the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Astronauts’ Hall of Fame, a video 20 minutes in length.

While the Bicentennial Series videos next week exemplify the astounding technological progress of the modern age, this week’s “From the Local History Room” column looks back to an important aspect of the push for moral and cultural progress in Illinois. This will we will take a trip back to the days of the slavery abolition movement, which made its mark in Pekin and Tazewell County, as it did in many other communities in the Northern States. The “Pekin Centenary 1849-1949” volume presents an enlightening narrative of that important time in our local history.

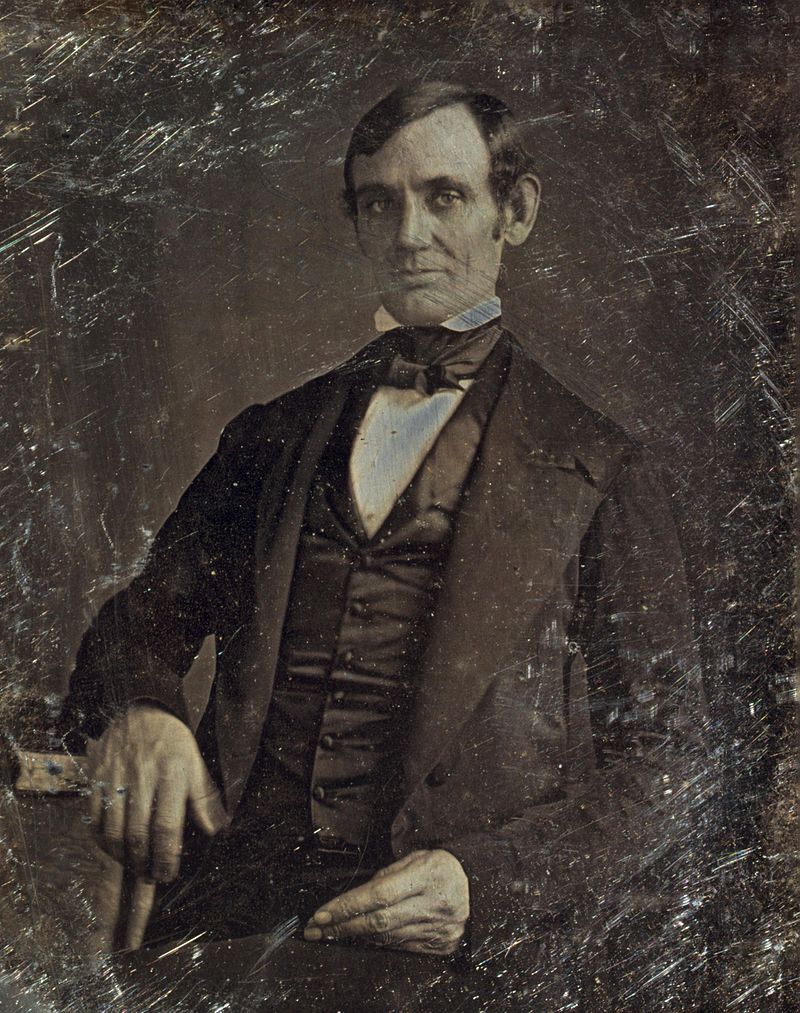

As we have seen from earlier columns in our Illinois Bicentennial Series, although Illinois was a “free” state, pro-slavery sentiment was predominant throughout southern and central Illinois. In our area, according to the Centenary (p.15), “Pekin was a pro-slave city for years. Some of the original settlers had been slave-owners themselves, and the overwhelming sentiment in Pekin was Democratic. Stephen A. Douglas, not Abraham Lincoln, was the local hero, although Lincoln was well-liked, and had some German following.”

Lincoln, of course, was one of Illinois’ leading abolitionist attorneys and politicians, and in 1841 he argued and won a case before the Illinois Supreme Court that secured the freedom of “Black Nance,” a Pekin resident who was the former slave of Nathan Cromwell, whose wife Ann Eliza had chosen Pekin’s name. On Oct. 6, 1858, Lincoln and his fellow abolitionist politician, U.S. Senator Lyman Trumbull, came to Pekin and addressed a large crowd in the court house square. (Trumbull would later co-author the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution outlawing slavery.)

It was largely due to the influx of German immigrants into Pekin, many of whom had fled religious persecution in their home countries, that abolitionist sentiment began to flourish in our city. Many Baptists were abolitionists, and in 1853 a German congregation of Baptists organized in Pekin – the origin of Pekin’s Calvary Baptist Church.

Among Pekin’s abolitionist leaders, according to the Pekin Centenary, was Dr. Daniel Cheever, who engaged in Underground Railroad activities from his home at the corner of Capitol and Court streets (and whose farm near Delavan was a depot on the Underground Railroad), by which runaway slaves were helped to escape to Canada. Other early Pekin settlers active in the abolitionist movement were the brothers Samuel and Hugh Woodrow (Catherine Street was named for Samuel’s wife, and Amanda Street was named for Hugh’s). The Woodrows aided runaway slaves at their homes in the vanished village of Circleville south of Pekin.

With the onset of the Civil War in 1861, Illinois cities such as Pekin and Peoria were divided between the pro-slavery element, who favored the Confederacy, and the abolitionist and pro-Union element. In the early days of the war, a secessionist organization calling itself the “Knights of the Golden Circle” (which was something of a precursor to the Ku Klux Klan) boldly worked in support of secession and slavery. The Centenary says the Knights were “aggressive and unprincipled,” and “those who believed in the Union spoke often in whispers in Pekin streets and were wary and often afraid.”

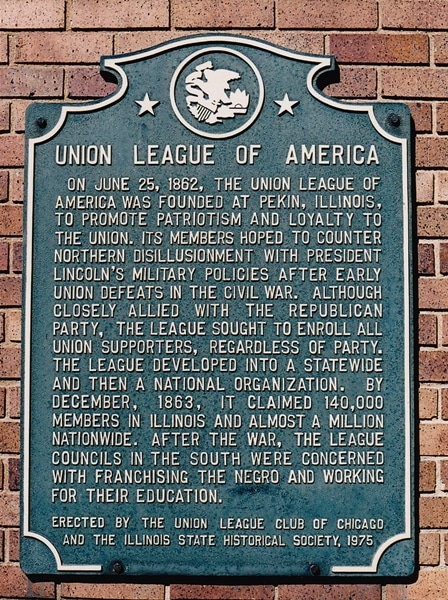

To counter the dominance of the Knights and promote the cause of the Union, a secret meeting was held on June 25, 1862, above Dr. Cheever’s office at 331 Court St., where 11 of Pekin’s early settlers formed the Union League to promote the cause of Union and abolition. The anti-slavery Germans of Pekin quickly became active in the League. Soon a chapter of the Union League was organized in Bloomington, and then an important chapter in Chicago, where John Medill, founding publisher of the Chicago Tribune, was a leading member.

Very soon the Union League had “swept the entire North and became a great and powerful instrument for propaganda and finance in support of the War” (Pekin Centenary, p.21). After the war, the League became a Republican Party social club, but would carry on its abolitionist legacy through support of civil rights for African Americans.

The 11 founding members of the Union League were the Rev. James W. N. Vernon, Methodist minister at Pekin; Richard Northcroft Cullom, former Illinois state senator; Dr. Daniel A. Cheever, abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor; Charles Turner, Tazewell County state’s attorney; Henry Pratt, Delavan Township supervisor; Alexander Small, Deer Creek Township supervisor; George H. Harlow, Tazewell County circuit clerk; Jonathan Merriam, stock farmer who became a colonel in the Union army; Hart Montgomery, Pekin postmaster; John W. Glassgow, justice of the peace; and Levi F. Garrett, Pekin grocery store owner and baker.

The building where these 11 men gathered in June 1862 was later the location of the Smith Bank and Perlman Furniture in downtown Pekin. Perlman Furniture burned down in 1968 and a few years later Pekin National Bank was built on the site. Plaques commemorating the Union League’s founding are displayed inside and on the outside of the bank building.