Our nation this weekend will mark the 82th anniversary of the Empire of Japan’s sneak attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 Dec. 1941 that triggered the United States’ entry into World War II on the side of the Allies. From that point until the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany and Japan in 1945, the entirety of America’s military, industrial, and spiritual might was committed to the war effort.

By the war’s end, the U.S. had lost over 400,000 soldiers in a global shedding of human blood that included anywhere from 21 million to 25.5 million military deaths, 29 million to 30.5 million civilian deaths due to war or to crimes against humanity, and another 19 million to 28 million civilian deaths due to war-related famine and disease. The horrific human cost of the genocidal aims and expansionist ambitions of Germany, Italy, Japan, and the U.S.S.R. was an estimated 75 million to 85 million souls.

Most fittingly, the generation in America who bore that terrible burden of suffering, and who afterwards exerted themselves to rebuild and repair their broken world, has come to be known as “The Greatest Generation” (a title bestowed on them by retired NBC anchorman Tom Brokaw). With the blessed conclusion of that conflict receding further and further into the past – it’s now been more than 79 years since the end of World War II – the numbers of the Greatest Generation’s members have dwindled away, and with each day that passes there are fewer and fewer men and women of that generation left to us.

These were the fathers and mothers, the grandfathers and grandmothers, and great-grandfathers and great-grandmothers of the current generation. My own father, Joseph, was one of them – but he wasn’t old enough to be drafted until December of 1945, so he avoided all the fighting, instead spending what he says was the most boring year of his life in the U.S. Army’s peacekeeping forces near Manila in the Philippines. How stark is the contrast between his experience and that of those who had liberated the Philippines from Japanese occupation a year before – not to mention the experience of his older brothers who fought in Europe and the Pacific.

It is to help us to remember those times that the Pekin Public Library has provided opportunities during Pekin’s Bicentennial year to view oral histories such as “World War II POW Stories” (which was shown last month on Nov. 16) and “We Were There: World War II” (which will close out the library’s Bicentennial video series on Saturday, Dec. 14, at 2 p.m.).

The library has a wide area of books and videos on World War II in its circulating collection. The above mentioned videos, however, are just two items among the resources related to the history of World War II that may be found in the library’s Local History Room Collection.

The three most notable World War II-related items in the Local History Room are three books that compile the stories of Tazewell County’s “Greatest Generation.”

Two of those volumes were the work of the late Robert B. Monge of Pekin, who in 1994 authored and edited “WW2 – Memories of Love & War: June 1937-June 1946,” a hefty 991-page book that collects personal stories, newspaper reports, and obituaries of Tazewell County World War II veterans and fallen heroes. Dedicated “to all of the men and women of Tazewell County who made the supreme sacrifice during World War II” and extending to 991 pages including index, photographs and illustrations, Monge’s book tells of his own wartime experiences, weaving his story together with the larger historical narrative of the war, along with the stories of many other men from Tazewell County who fought in World War II or were killed in action.

Monge was a 1943 graduate of Pekin Community High School. That same year, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps, as a member of which he fought against Japanese forces in the Pacific Theater. He was discharged with the rank of Corporal on 17 June 1946. After the war, he and his brothers went into business together, founding Monge Bros. Construction. In 1955, he became president of Monge Realty and Investments Inc. in Pekin. While he was best known for his work developing new subdivisions in Pekin, Monge also came to feel a strong desire to record the wartime history of Tazewell County’s men who had been sent off to fight.

Three years after his first volume, in 1997 Monge collaborated with Jack Shepler and the Tazewell County Veterans Memorial Committee to produce the 261-page “Book Eternal: Tazewell County Veterans Memorial,” which tells of the planning and construction of the county’s Veterans Memorial located at the Tazewell County Courthouse lawn in downtown Pekin. “Book Eternal” also lists those whose names are inscribed on the memorial’s stones, which display the names of every Tazewell County soldier who died in the service of his country.

The many stories in Monge’s first book often provide firsthand accounts of the harrowing ordeals that were endured by the young men sent into battle to put a stop to the racist and imperialist aggression of the Nazis and Fascists in Europe and North Africa and the Empire of Japan in the Pacific and Asia. In addition to his own memories, or those, for example, of his fellow Marine Chuck Dancey who passed away in January of this year, or of the late John T. McNaughton and numerous other veterans who came back from the war, Monge frequently reprints or adapts newspaper reports of local boys killed or reported missing in action. The newspaper reports or obituaries, along with Monge’s larger historical narratives of the war, are informative but not graphic or sensationalized. However, due to the nature of modern warfare, and especially due to the monstrous ideologies that motivated the enemy, the personal narratives in Monge’s book at times make for some grim reading.

A decade later, in 2007 the Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society compiled its own book on the experiences of our local World War II veterans: “Tazewell County Veterans of World War II: Remembrances – Pearl Harbor to V-J Day,” which extends to 488 pages.

About 11 years ago, former Pekin Public Library Reference Librarian Laurie Hartshorn collected and compiled the wartime stories and recollections of 16 local women. Their personal memories are collected in “Women of the Greatest Generation Tell Their Stories.”

The Local History Room Collection also has archival boxes and files of newspaper clippings and World War II-era magazines, and even several donated complete issues of the Pekin Daily Times from those years.

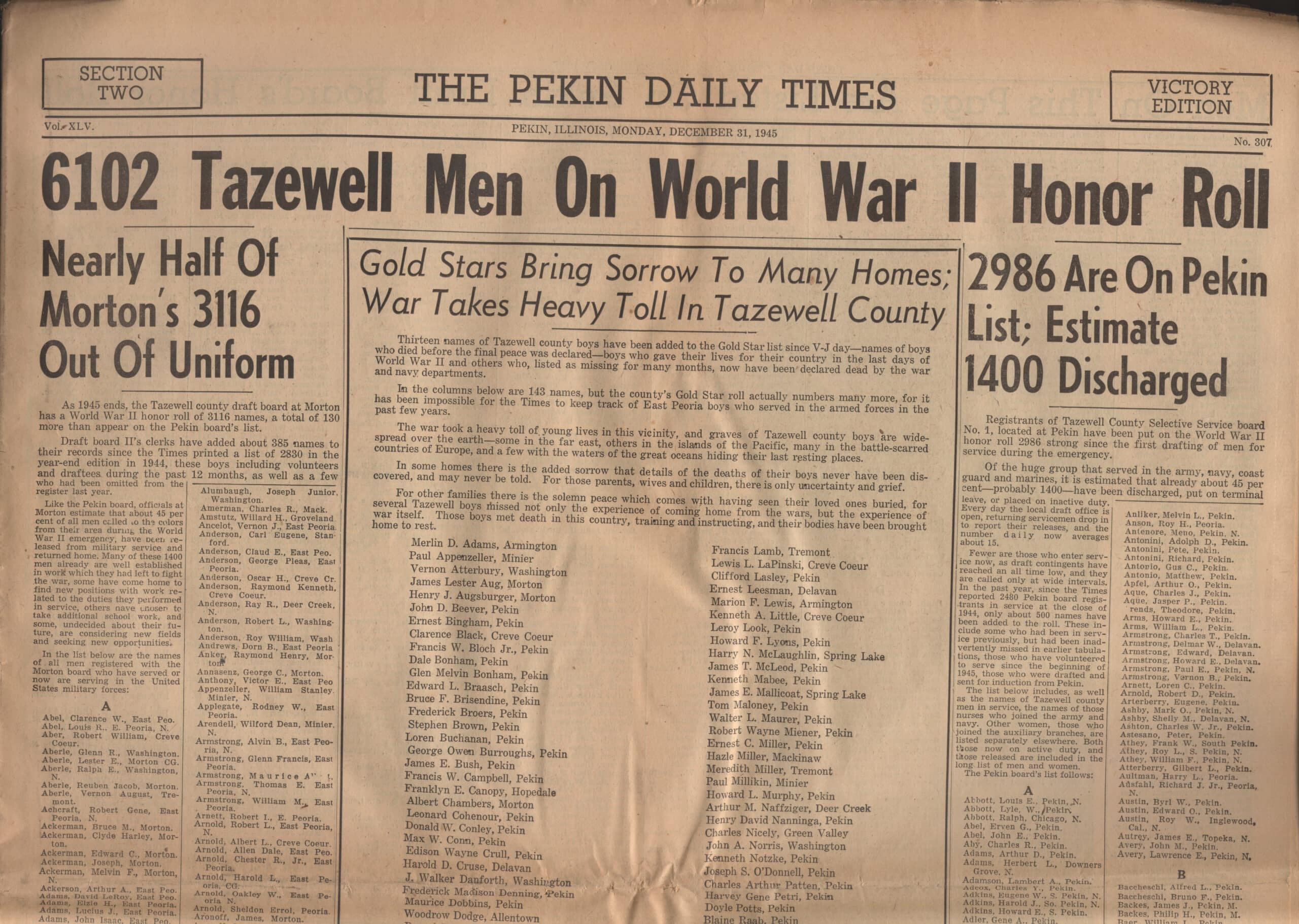

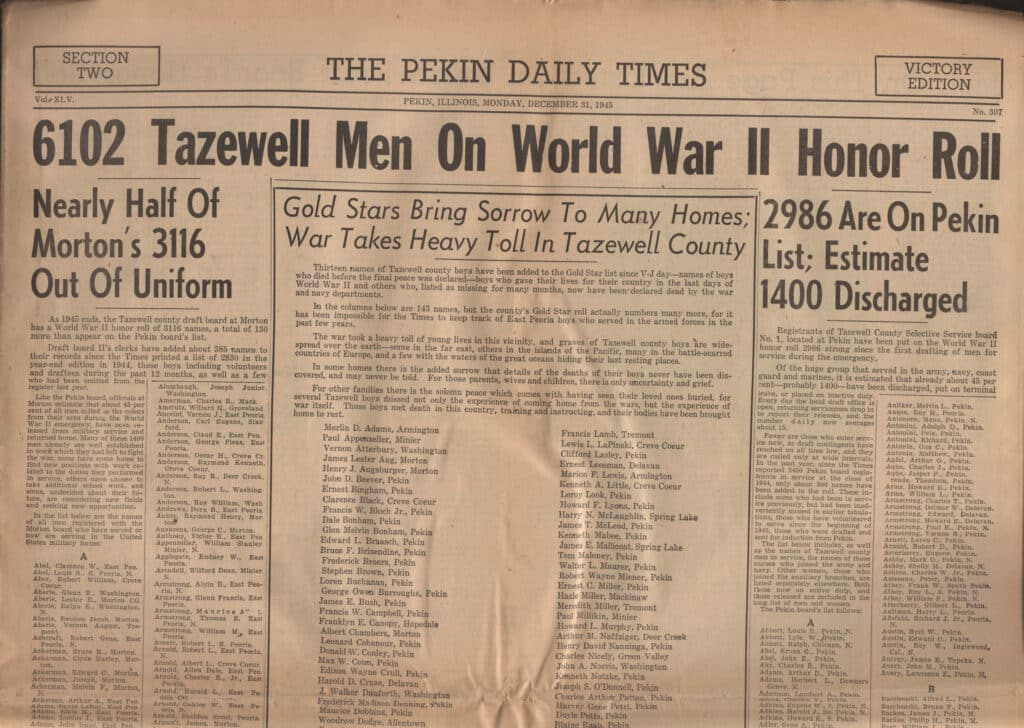

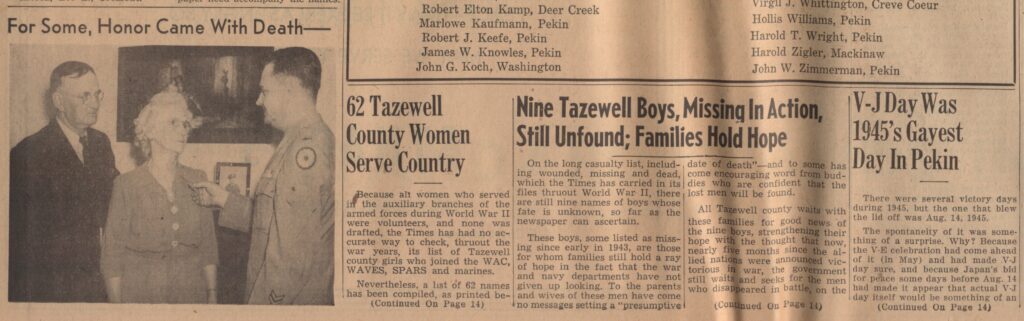

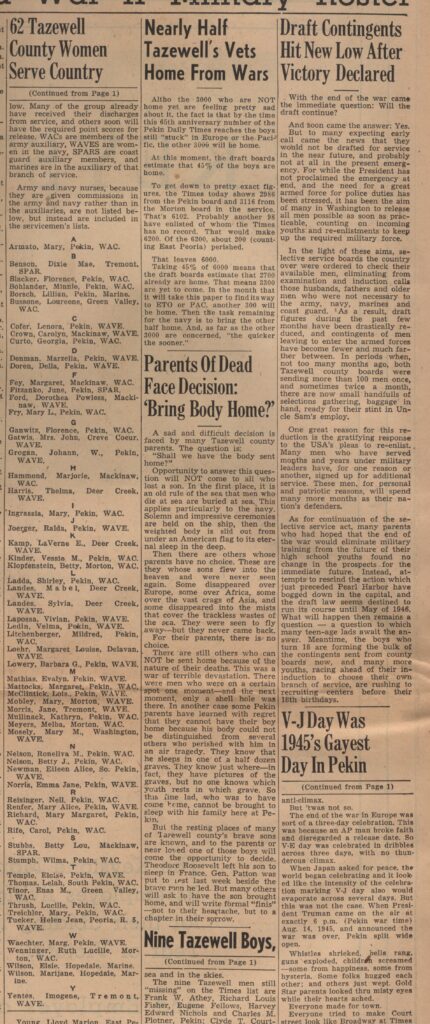

One of those newspapers is the “Victory Edition” of the Pekin Daily Times, published 31 Dec.1945. The Daily Times that year devoted its traditional “Year In Review” issue to a look back over the nation’s and Pekin’s experiences of the previous four years, preparing and publishing a list of 143 young men from Tazewell County who had been killed in the war, along with extensive Draft Board lists of names of men from Pekin and Morton who been called up to serve their country, including the county’s women who had volunteered as Army and Navy nurses.

Section Two of this special edition is headlined, “6102 Tazewell Men On World War II Honor Roll,” with other headlines including, “Nearly Half of Morton’s 3116 Out of Uniform” and “2986 Are On Pekin List; Estimate 1400 Discharged.” A separate story, “62 Tazewell County Women Serve Country,” is devoted to the honored group of women who had volunteered as WACs (Women’s Air Corps), WAVES (women in the Navy), SPARS (Coast Guard auxiliary), and the Marines women’s auxiliary force.

The special edition also struck a somber tone, however, reminding its readers of “Nine Tazewell Boys, Missing In Action, Still Unfound; Families Hold Hope.”

But the mood throughout those yellowed pages was chiefly one of gratitude and joy – gratitude for those who had fought for freedom, and joy that the war was over and peace had returned. Looking back to celebrations and the utter relief at Japan’s surrender that ended the war – “V-J Day,” “Victory-over-Japan Day” – the special edition recalled that “V-J Day Was 1945’s Gayest Day In Pekin.”

In the introductory remarks to his 1994 book, Monge explained why he felt driven to devote several years of his life to writing his book:

“What must man do to preserve the memory of men who made the ultimate sacrifice – at a time when it meant so much to the world? There comes a time when we must sacrifice our time and energies and make it our duty to do it. Out of W.W. II came a multitude of heroes – those who died on the battlefield and those who lived through its holocaust. . . .

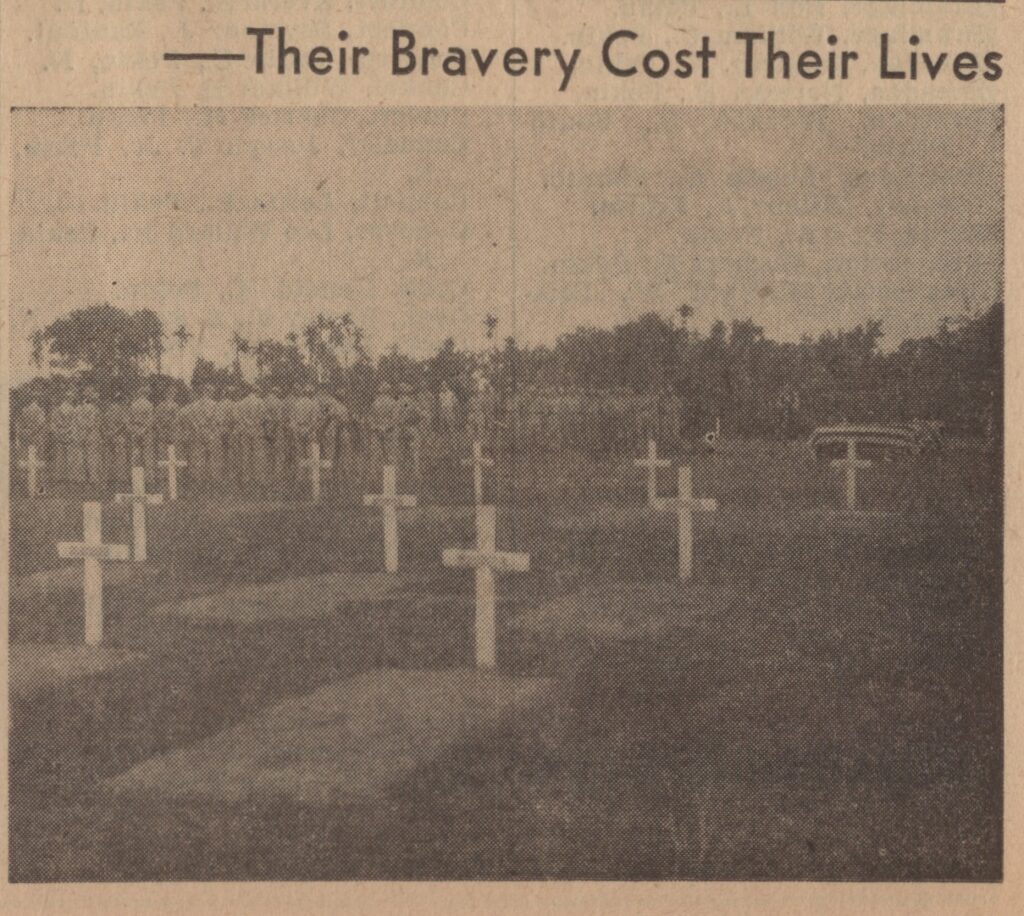

“. . . I found that the families of Tazewell County gave more freely of their sons in all our wars than the country ever expected or required. The dark cobwebs in lost graveyards hide many young men and boys who gave their lives in a past war somewhere. I felt that, at all costs, we must prevent them from being lost in the oblivion of time.

“Probably it was said best by an early author of Tazewell County history: ‘To be forgotten has been the great dread of mankind from the remotest ages.’ All will be forgotten soon enough, in spite of their fame and glory and in spite of our efforts to preserve their memory.

“This is for the present generation to read and find out about their kind and what they stood for and what they died for. It is also for our generation too, to relive the past, in one of the most tumultuous periods in all history, and to remember our dead. Time and its greed cuts everyone down into oblivion. It eventually completes the destruction of the physical man and his cemetery stones, erected in his memory. Eventually they will crumble into dust and blow away – but the preservation of their accomplishments, deeds and their supreme sacrifice will be saved for future generations.”

The ranks of our surviving World War II veterans have grown very thin as that generation recedes into history – but when the last of them is gone, books such as Monge’s will enable future generations to remember their sacrifices. In keeping with what Monge wrote, may we never forget the men and women of that generation whose names are, or soon will be, written in God’s Book Eternal.