On Friday, March 2, at 11 a.m., the Pekin Public Library will present the third video in its Illinois Bicentennial Series in the Community Room. The video that will be shown is 34 minutes in length and is entitled, “Farming in Tazewell County During the ’30s and ’40s,” presented by Tom Finson. Like last month’s Finson video, it includes vintage film footage from around the county. Admission is free and the public is invited.

For the pioneer settlers of central Illinois, farming wasn’t merely a business, but was crucial for a settler family’s survival. Our column this week recall the first of the post-War of 1812 settlers in our area.

The summer before Illinois was admitted as the 21st state of the Union in 1818, a territorial census counted 40,258 souls living in the soon-to-be state – but the new state’s population rapidly increased over the next decade. Up to that time, American settlers in Illinois had come chiefly from southern states and had settled almost exclusively in southern Illinois.

But with the dawn of statehood a new wave of migration arrived, in which settlers from southern Illinois began to move north, joined by newcomers from states north of the Ohio River. These new arrivals to central Illinois came up the Illinois River or overland from southern Illinois to Fort Clark (Peoria) and its environs – and as we shall see, these newcomers included William Blanchard and Nathan Dillon, names prominent in early Tazewell County history.

As we saw previously, American soldiers built Fort Clark in 1813 on the ruins of the old French village of La Ville de Maillet, which Capt. Thomas Craig had burned the year before during an Illinois militia campaign meant to warn the Indians of Peoria Lake not to ally with Britain during the War of 1812 (but which likely had the opposite effect).

In relating the story of Craig’s burning of the French village, S. DeWitt Drown’s “Peoria Directory for 1844” says (italics as in original), “Capt. Craig excused himself for this act of devastation, by accusing the French of being in league with the Indians, with whom the United States were at war; but more especially, by alledging (sic) that his boats were fired upon from the town, while lying at anchor before it. All this the French have ever denied, and charge Capt. Craig with unprovoked, malignant cruelty.”

Craig’s accusation that the French Americans of Peoria Lake were in league with Indians hostile to the U.S. was based on the fact that the French not only lived peaceably with the tribes of the area, but even sometimes intermarried with them. But the tribes of Peoria Lake had declined to join Tecumseh’s confederacy and were considered to be friendly until the unprovoked attacks of Territorial Gov. Ninian Edwards and Capt. Craig.

The destruction of La Ville de Maillet essentially ended the French phase of the European settlement of central Illinois – afterwards only the French fur traders of Opa Post at the present site of Creve Coeur were left in the area. The early historians of Peoria and Tazewell counties tended to disparage the early French settlers of central Illinois, even to the point of claiming that they weren’t really settlers at all. For example, Charles C. Chapman’s 1879 “History of Tazewell County” described the men and women of Opa Post in this way:

“These French traders cannot be classed as settlers, at least in the light we wish to view the meaning of that term. They made no improvements; they cultivated no land; they established none of those bulwarks of civilization brought hither a half century ago by the sturdy pioneer. On the other hand, however, they associated with the natives; they adopted their ways, habits and customs; they intermarried and in every way, almost, became as one of them.”

Chapman’s comments reveal that his disparaging appraisal of the French fur traders was due not only to disdain for the social class and lifestyle of a fur trader, but also the pervasive racist bias against Native Americans that spread westward with American expansion. Other influences included the age-old enmity between England and France that stemmed from the medieval Hundred Year’s War, with religious estrangement and animosity between Protestants and Catholics also thrown into the mix.

Those same attitudes toward the Indians and the French were also exhibited by Charles Ballance in his 1870 “History of Peoria.” In his history, Ballance argues at length that the French Americans of La Ville de Maillet were culturally and socially greatly inferior to the Americans of British origin who supplanted them, finding fault with the style of the homes they built and even denying the reports of the village’s former inhabitants that their settlement included a wine cellar and a Catholic church or chapel. Maybe behind Ballance’s common ethnic, racial, and social disdain for the Indians and French, there was an uneasy conscience over the fact that the city of Peoria of Ballance’s day only existed because the French settlement had been wiped out in 1812.

The construction of Fort Clark at the site of the French village in 1813 planted the seed of the present city of Peoria, for a new village quickly grew up around the fort (the site is today Liberty Park on the Peoria Riverfront, at Liberty and Water streets). According to Chapman, the fort itself burned down five years later. But in 1819, one year after Illinois statehood, the pioneer founders of Peoria arrived: Joseph Fulton, Abner Eads, William Blanchard (1797-1883), and four other men, who had traveled by keelboat and on horseback.

The next few years saw the arrivals of even more settlers. In 1825 the state legislature created Peoria County, which originally covered a large area of central and northern Illinois, including the future Cook County and the soon-to-be formed Tazewell County. Ten years later, Peoria was officially incorporated as a town, and by 1845 Peoria was large enough to incorporate as a city.

Three years after William Blanchard’s arrival at Fort Clark, he and a few companions crossed Peoria Lake to present-day Fon du Lac Township in Tazewell County, building a dwelling and growing crops south of the future Woodford County border. Here is how Chapman told the story of Blanchard’s earliest pioneer activities:

“Wm. Blanchard, Jr., is a native of Vermont, where he was born in 1797; left that State when seven years of age, and with his parents went to Washington Co., N. Y., where his father, William, died. When seventeen years of age he enlisted in the regular army, and took an active part in the war of 1812, serving five years, when he, with Charles Sargeant, Theodore Sargeant and David Barnes, veterans of the war, started West, coming to Detroit, Mich., thence to Ft. Wayne, whence they journeyed in a canoe to Vincennes, thence to St. Louis. From there they came up the Illinois in a keel boat manned by a fishing crew, and commanded by a man named Warner, and landed at Ft. Clark, now Peoria, in the spring of 1819.

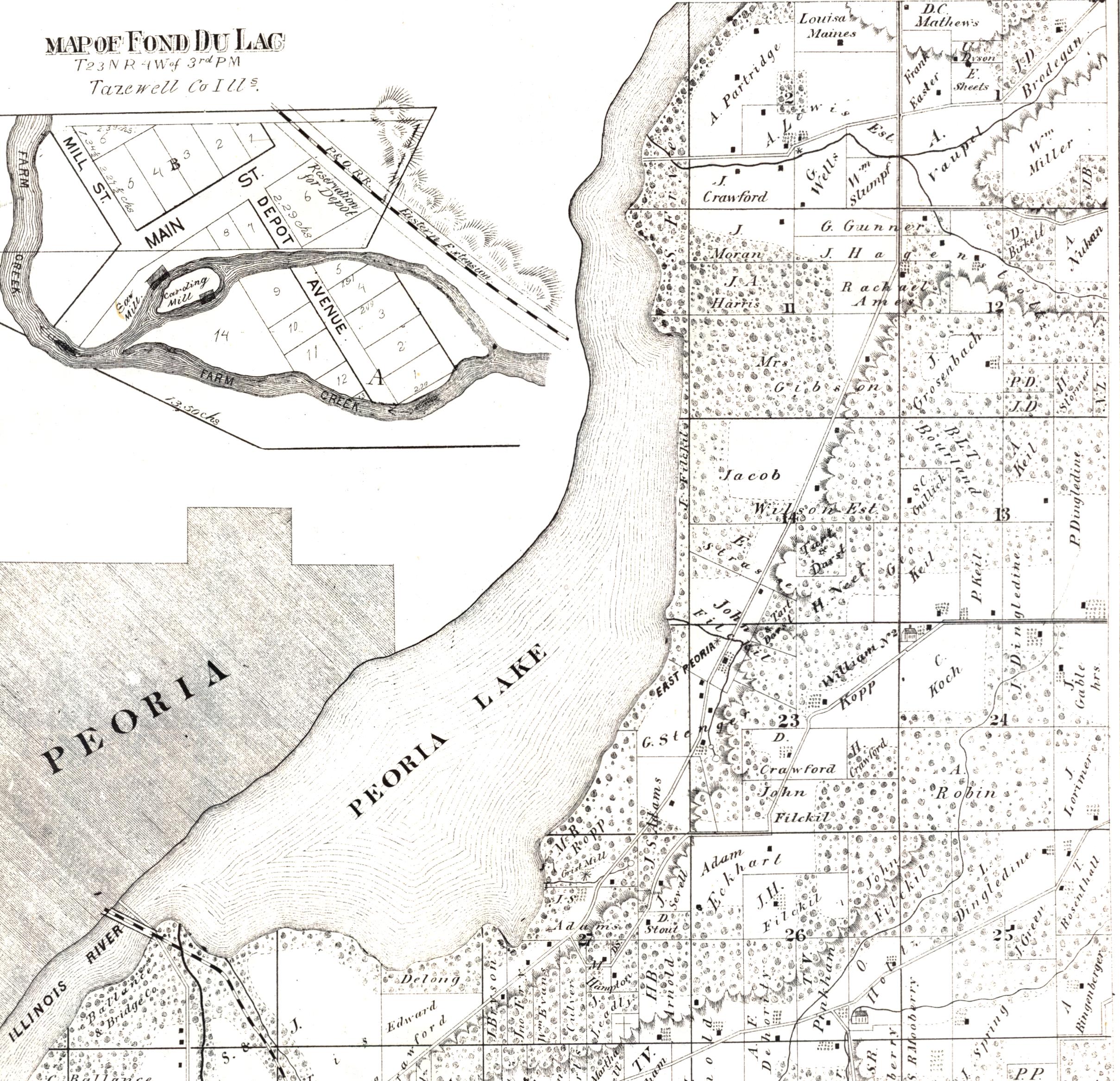

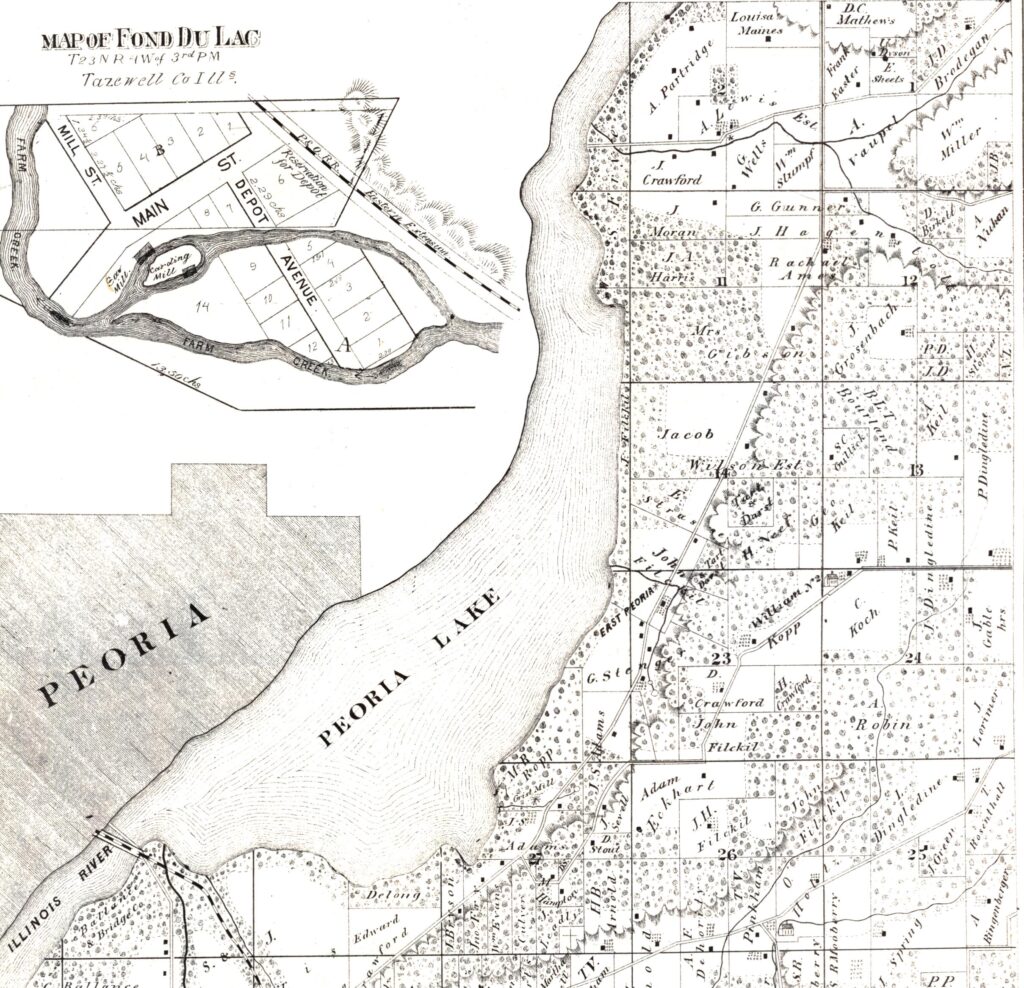

“Crossing the river to what is known as the bottom lands they found a cleared spot, and with such tools as they could arrange from wood put in a patch of corn and potatoes. This land is now embodied in Fond du Lac township. Looking farther down the stream they found, in 1822, an old French field of about ten acres, on which they erected a rude habitation, and soon this soil was filled with a growth of blooming corn and potatoes. This was the first settlement between Ft. Clark and Chicago, and was the first dwelling erected. The site is now covered by the fine farm of Jacob Ames.”

designated on the map as land owned by “Rachael Ames” — is shown in Sections 11 and 12 of Fondulac Township, around the area of Grosenbach Road. William Blanchard’s “rude habitation” is said to have been built in 1822 on land that later was included in the farm of Jacob Ames.

One year before Blanchard came to the future Tazewell County, North Carolina native Nathan Dillon (1793-1868) brought his family overland from Ohio to Sangamon County, first dwelling on Sugar Creek south of Springfield. Dillon then struck out north, arriving in the future Tazewell County in 1823.

Dillon has traditionally been called Tazewell County’s first white settler, but he arrived here a year after Blanchard and long after the Frenchmen of Opa Post. The confusion arose from the haste with which Chapman’s 1879 Tazewell County history was compiled and edited – Chapman didn’t learn that Blanchard preceded Dillon until the printing of his book was underway, so Chapman’s book at first states that Dillon was the earliest, then later on corrects and apologizes for that error. The monument at Dillon’s grave erroneously pronouncing him the county’s first white settler stems from Chapman’s mistake.

But regardless who was first, Blanchard and Dillon both possessed pioneering courage and grit, paving the way for many others who were soon to follow.

Next week we’ll review the story of the creation of Tazewell County.