This is a reprint of a “From the Local History Room” column that first appeared in November 2014 before the launch of this weblog.

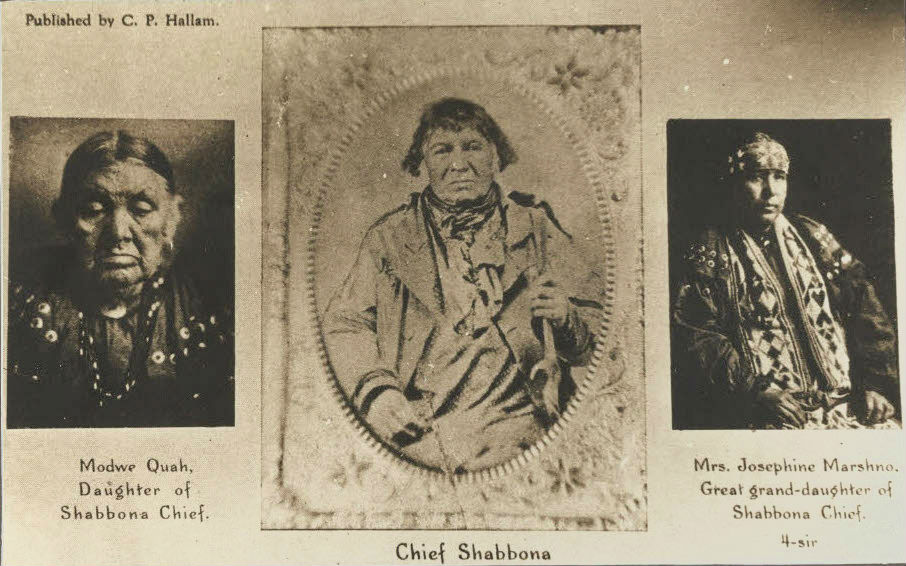

When settlers of European descent first began to make permanent dwellings during the 1820s in what would soon become Tazewell County, they found the area inhabited by Native American tribes. The most numerous of the tribes was the Pottawatomi, who had villages in the county’s northern townships, as well as a large village at the future site of Pekin, where they were led by a chief named Shabbona.

As this column has previously related, Shabbona was a member of the Ottawa tribe who had married the daughter of a Pottawatomi chief and succeeded to the headship of his wife’s group of Pottawatomi after her father’s death. Shabbona and his family are reported to have camped to the south of where Pekin’s pioneer settler Jonathan Tharp had built his log cabin in 1824. Other Pottawatomi in the area were headed by a chief named Wabaunsee. During the Black Hawk War of 1832, however, Shabbona and Wabaunsee refused to join Black Hawk’s uprising, and Shabbona even gave active help to white settlers, warning them of impending attack. Consequently, after the war, Shabbona and Wabaunsee were rejected as chiefs, and, according to the online essay “Potawatomi War Chief (1744-1831) Chief Senachwine,” the Pottawatomi instead chose as their leader Kaltoo, also called Ogh-och-pees, eldest son of the Pottawatomi War Chief Sen-noge-wone.

In central Illinois, Sen-noge-wone is more usually called “Senachwine.” In his “History of Tazewell County,” Charles C. Chapman spells the name “Snatchwine.” He and his people dwelt in and near what would become Washington Township. On pages 674-676, Chapman records some memories of Lawson Holland, an early white settler of Washington Township. Holland’s memories included recollections of Chief Senachwine and of the customs of the Pottawatomi of the area. Holland knew Senachwine for about 10 years, remembering him as often despondent.

Chapman writes that Senachwine “was honored and loved by all the braves,” and that “his word was law, and his presence and council always sought in times of disturbance or trouble. Among the whites he was generally honored and respected. To them he always extended the hand of welcome, and the fatted deer of the forest was brought to their door in token of good will.”

Chapman’s account of Chief Senachwine also includes the transcript of a lengthy speech of the chief’s. According to Chapman, Senachwine gave the speech around 1823 when he “found out the whites were becoming alarmed, and called a council with the whites, to talk. He spoke about four hours.”

“When you palefaces came to our country we took you in and treated you like brothers,” Senachwine said. “We furnished you with corn and gave you meat that we killed, but you palefaces soon became numerous and began to trample upon our rights, which we attempted to resist, but was whipped and driven off. This is returning evil for good. The graves of my forefathers are just as dear to me as yours, and had I the power I’d wipe you from the face of the earth. I have 800 good warriors, besides many old men and boys, that could be put in a fight, but this takes up a remnant of these tribes since the last war. I believe I could raise enough braves, and taking you by surprise, could clean the State. I know I could go below your capital and take everything clean. But what then? We must all die in time. You would kill us all off. You tell me that you have forbidden your men to sell whisky. You enforce these laws and I stand pledged for any depredation my people shall commit. But you allow your men to come with whisky and trinkets and get them drunk and cheat them out of all their guns and skins and all their blankets, that the Government pays me yearly for this land. This leaves us in a starving freezing condition and we are raising only a few children compared to what we raised in Old Kentuck, before we knew the palefaces. Some of my men say in our consultations, let us rise and wipe the palefaces from the face of the earth. I tell them no, the palefaces are too numerous. I can take every man, woman and child I’ve got and place them in the hollow of my hand and hold them out at arm’s length. But when I want to count you palefaces I must go out in the big prairie, where timber ain’t in sight, and count the spears of grass, and I haven’t then told your numbers.”

About eight years later, around 1831, Senachwine counseled that violent resistance to white encroachment was futile and would only lead to the annihilation of the native tribes. His counsel and the policy of Shabbona convinced the Pottawatomi not to join Black Hawk in his hostilities. The online essay “Potawatomi War Chief (1744-1831) Chief Senachwine,” quotes him as responding to Black Hawk, “Resistance to the aggression of the whites is useless; war is wicked and must result in our ruin. Therefore let us submit to our fate, return not evil for evil, as this would offend the Great Spirit and bring ruin upon us. . . . My friends, do not listen to the words of Black Hawk, for he is trying to lead you astray. Do not imbrue your hands in human blood . . . .”

Senachwine died in the summer of 1831 and was buried on a bluff above his village in Putnam County. After the Black Hawk War, the Pottawatomi were deported to reservations in Kansas and Nebraska, but in subsequent years members of his band reportedly would come back from time to time to visit his grave. On June 13, 1937, the Peoria Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution placed a large stone with a bronze memorial plaque at the spot that was believed to be his grave site, about a half-mile north of the village of Putnam. Five members of the Prairie Band Potawatomi came from Kansas to attend the ceremony.