In our series recalling the history of the Pekin Public Library, we have reached the point in the library’s history when a new day began to dawn – when the library moved into a building that was constructed specifically to be a library.

For the first 34 years of its existence, Pekin’s library made use of rented rooms in buildings along Court Street (apart from a brief stint when the library was housed in the old City Hall building at the southeast corner of Fourth and Margaret streets).

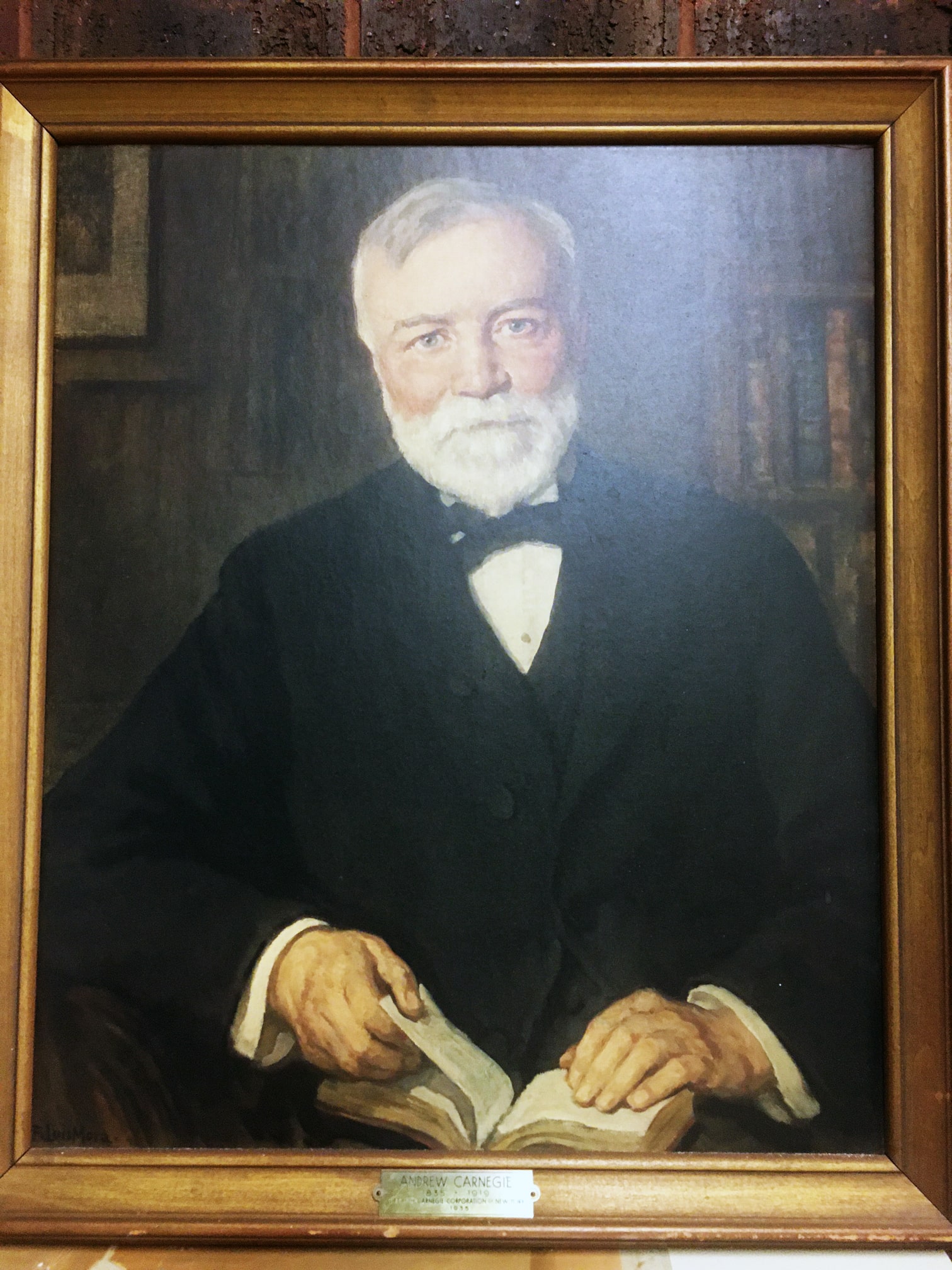

The seed of Pekin’s first library building was planted in July 1900, when library board member Mary E. Gaither on her own initiative decided to write a letter to the millionaire industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919), describing the needs and expenses of the Pekin Public Library, requesting his monetary assistance in the construction of a library building for Pekin. As we will explain further below, Carnegie responded favorably, enabling the Pekin library board to commence plans for the construction of a new building.

As Miss Gaither later reported her activities to the library board in Nov. 1900: “The opportunity being presented, I have acted upon it” – not waiting for the majority of her fellow board members to warm to the idea first.

In writing to Carnegie, Miss Gaither had not undertaken merely to write to random millionaires and ask for their help, hoping to find a willing ear. Rather, she wrote specifically to Carnegie because he had been issuing grants to fund the construction of “Carnegie libraries” all across the U.S. since 1883 – a grand philanthropic endeavor that caused Carnegie to be known as the “Patron Saint of Libraries.”

As stated at the website of the Digital Public Library of America’s history of U.S. public libraries, “Carnegie funded the building of 2,509 ‘Carnegie Libraries’ worldwide between 1883 and 1929. Of those, 1,795 were in the United States: 1,687 public libraries and 108 academic. Others were built throughout Europe, South Africa, Barbados, Australia, and New Zealand. The last Carnegie Library grant in the U.S. was issued in 1919.”

Born to poor Scottish Presbyterian parents in Dunfermline, Scotland, Carnegie came with his family to America when he was 13. Carnegie made his fortune in the steel industry, but as a young man he had developed a personal moral code – the “Andrew Carnegie Dictum” – by which he purposed to spend the first third of his life getting a good education, the second third of his life making money, and the last third of his life giving his money away rather than hoarding it away from the less fortunate.

By the end of his life, Carnegie had donated about $351 million to charitable causes – including the building of public libraries. Carnegie’s own experience in his youth had convinced him of the importance of libraries. As noted in the Digital Public Library of America’s sketch of Carnegie’s life, “A turning point for young Carnegie, which would help guide his work as a philanthropist years later, was spending Saturday afternoons at a local private library at the invitation of a wealthy Pittsburgh man.”

The same DPLA sketch notes further, “In his autobiography, Carnegie remembered that, as a child, ‘I resolved, if wealth ever came to me, that it should be used to establish free libraries.’ And he did, providing public libraries to communities across the country, all engraved, at his request, with an image of a rising sun and ‘Let there be light.’”

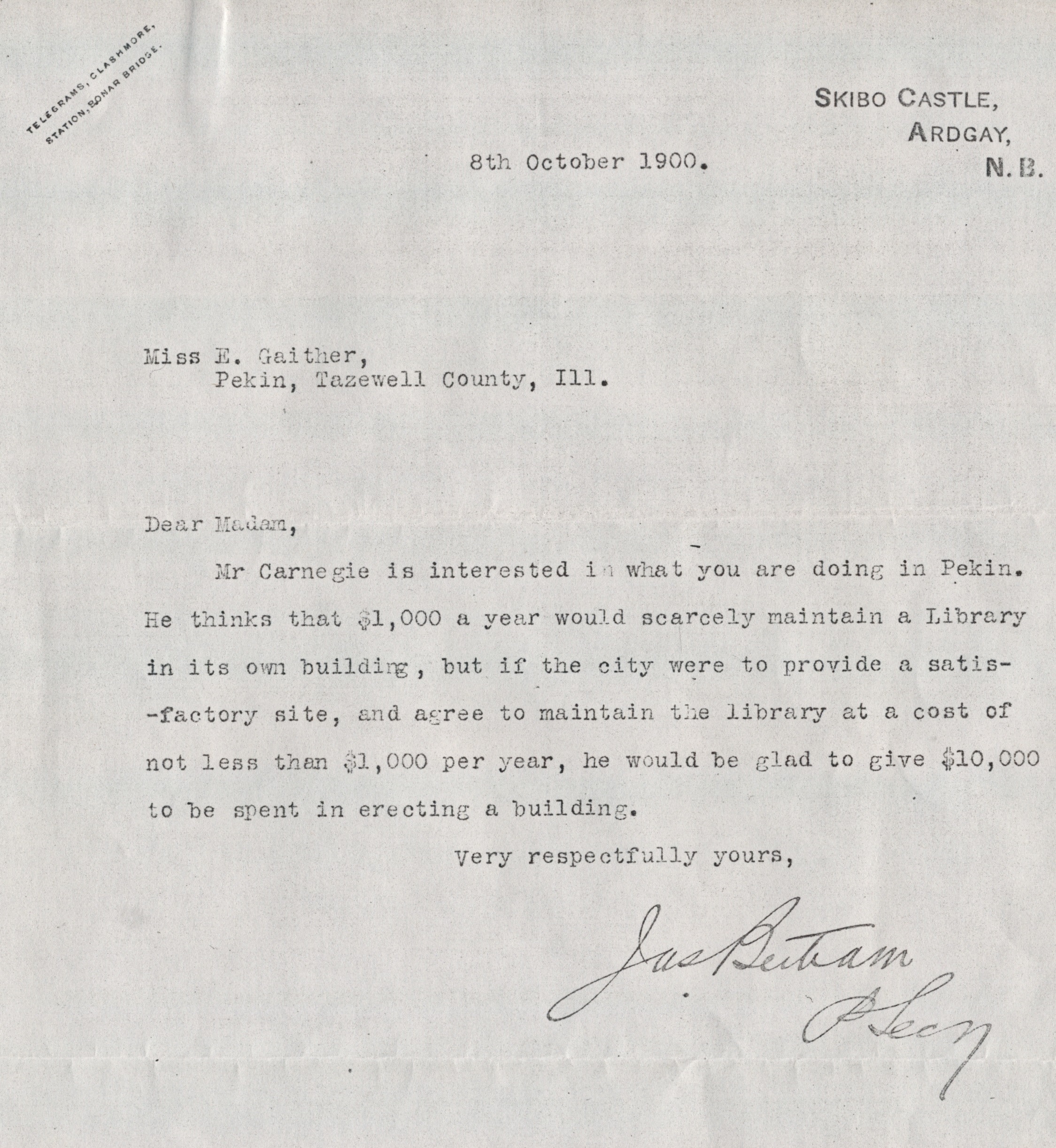

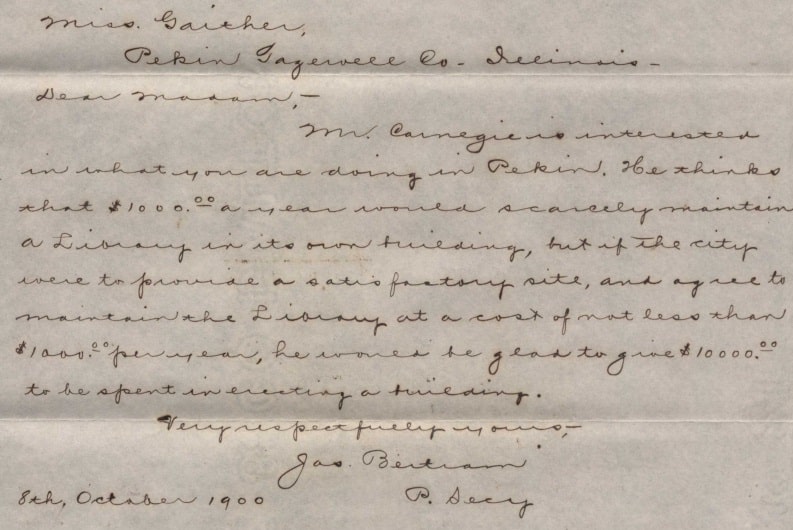

After Miss Gaither sent her letter to Carnegie, it was about three months before she received a reply. On Oct. 8, 1900, Carnegie’s private secretary James Bertram penned a letter to Miss Gaither. A copy of Bertram’s letter later was included in the 1902 library cornerstone time capsule, and reads as follows:

“Dear Madam, —

“Mr. Carnegie is interested in what you are doing in Pekin. He thinks that $1000.00 a year would scarcely maintain a Library in its own building, but if the city were to provide a satisfactory site, and agree to maintain the Library at a cost of not less than $1000.00 per year, he would be glad to give $10000.00 to be spent in erecting a building.

“Very respectfully yours, —

“Jas. Bertram, P. Secy”

Upon receipt of Bertram’s letter, Miss Gaither immediately moved on to the next phase of her campaign to get Pekin’s library a new building: finding a landowner willing to donate a building site. We will tell that part of the story, and place a special focus on Miss Gaither and her life, next week.