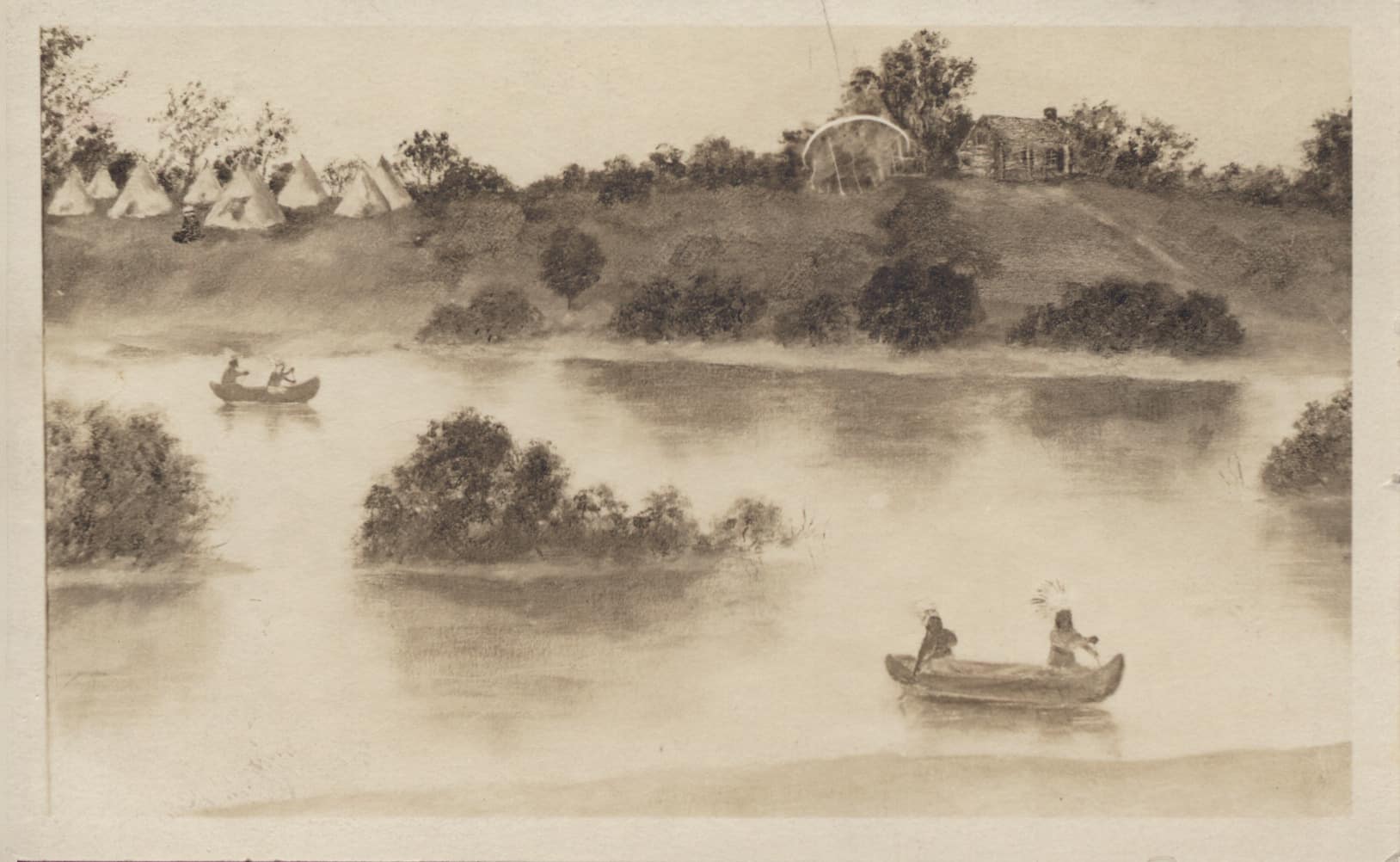

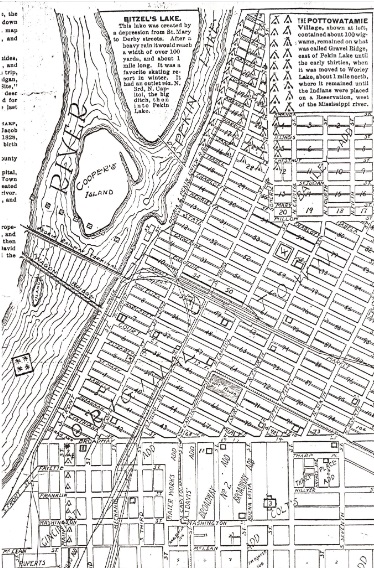

While Pekin traces its origin to the 1824 arrival of Jonathan Tharp from Ohio, the future site of Pekin and its environs was home to Native American tribes during the long centuries, even millennia, prior to the arrival of European explorers and settlers. As we have previously told, the city of Pekin was established at the site of a Native American village of about 100 wigwams located on Gravel Ridge along the eastern shore of Pekin Lake (near the location of the Pekin Boat Club). Tharp, Pekin’s first European-American settler, built his cabin to the south of that village, at or very near the spot where the Brotherton Museum (the former Franklin School) stands today, at the foot of Broadway.

The Native Americans who lived along Gravel Ridge in the 1820s and 1830s were primarily Pottawatomi, but much of Tazewell County also was home to Kickapoo bands. In a letter dated in May 1812, Illinois Territorial Gov. Ninian Edwards wrote, “At Little Makina, a river on the south side of [the] Illinois, five leagues below Peoria, is a band, consisting of Kickapoos, Chippeways, Ottaways and Pottowottamies. They are called warriors, and their head man is Lebourse or Sulky. Their number is sixty men, all desperate fellows and great plunderers.”

While Sulky was a Kickapoo, his other name “Lebourse” is French, for he was, like many Native Americans in Illinois during that period, partly of French descent, even as his own band was made up of warriors from three other tribes besides the Kickapoo. The name of the river that Gov. Edwards said was the location of Sulky’s village – “Little Makina” – might suggest that they were living on the shores of the Mackinaw River south of Pekin. The distance “five leagues below Peoria” indicates a spot about 17 miles downriver from Peoria Lake, which is the river distance between Peoria and Pekin, so “Little Makina” must refer to a stream or creek that flows into the Illinois – probably the present mouth of the Mackinaw River, which in those days emptied into the Illinois River in present Mason County. That means Sulky and his band were living at the future site of Pekin around May of 1812.

Another Kickapoo chief in Tazewell County, mentioned by Gov. Edwards in a letter written July 21, 1812, was Pemwotam (or Pemwatome), whose village was at the northeast end of Peoria Lake in Fondulac Township, to the north of the McClugage Bridge. On his raid of the Indian villages of Peoria Lake in Oct. 1812, Gov. Edwards destroyed Pemwotam’s Kickapoo village. In his 1879 “History of Tazewell County,” Charles C. Chapman gives a somewhat lengthy account of Edwards’ raid, describing the destruction of the Kickapoo village in Fondulac Township and of Pottawatomi chief Chequeneboc’s village in Woodford County. Chapman’s account is somewhat garbled, though, because he misidentifies Chequeneboc’s village with Chief Black Partridge’s village and confuses those villages with Pemwotam’s village in Fondulac Township. That error arose from the much-later memoir of John Reynolds and was subsequently repeated in later publications such as Chapman’s.

Chapman mentions another Kickapoo chief of Tazewell County named “Old Machina,” whose name is also spelled “Mashenaw.” Machina’s village was near Mackinaw, and Chapman related the pioneers’ recollections of Chief Machina’s displeasure at the new wave of settlers who arrived in the 1820s.

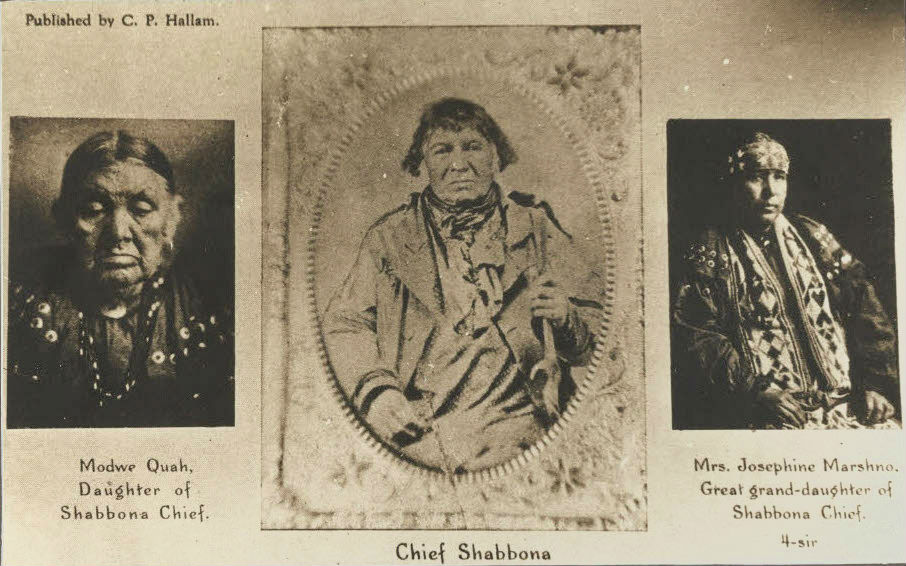

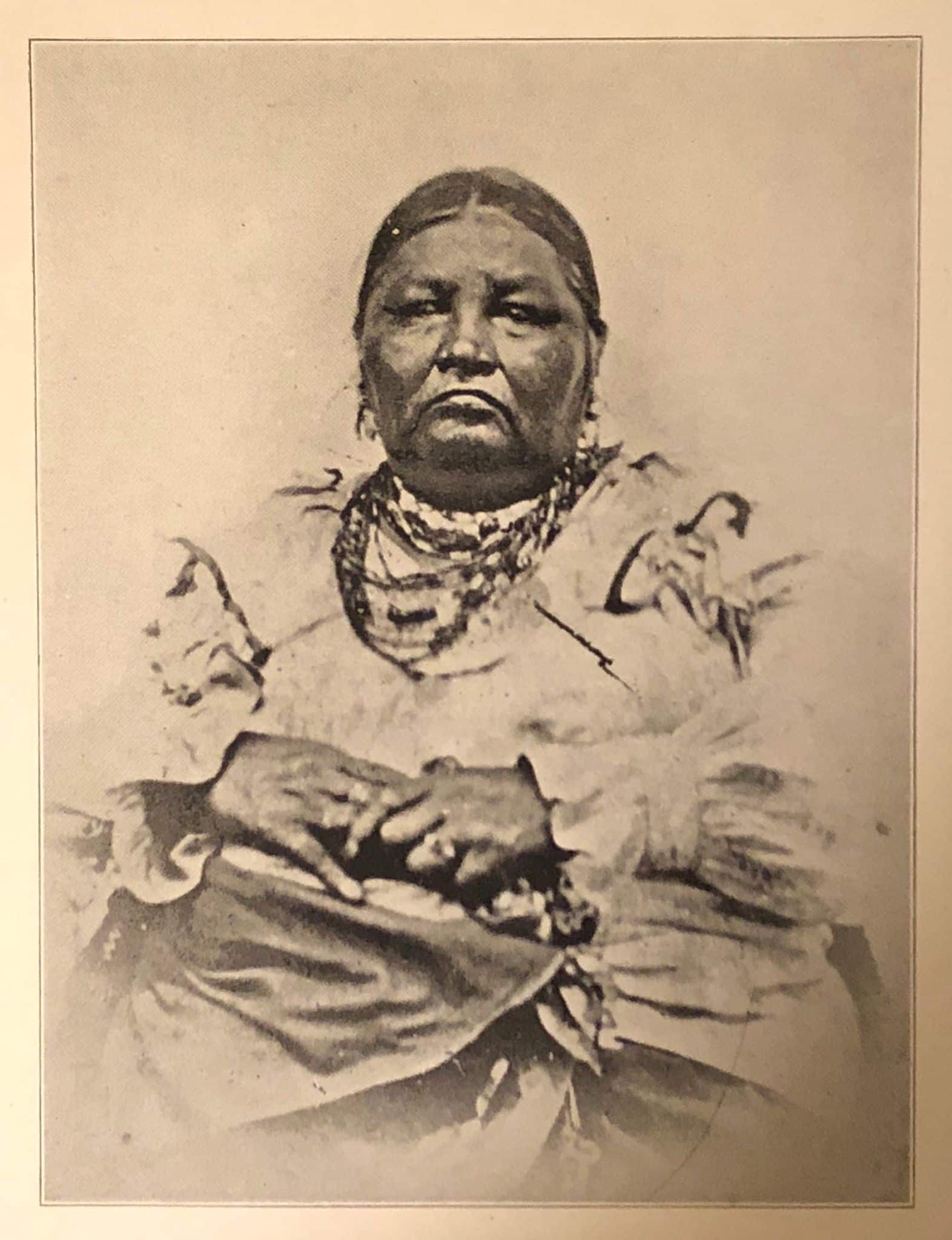

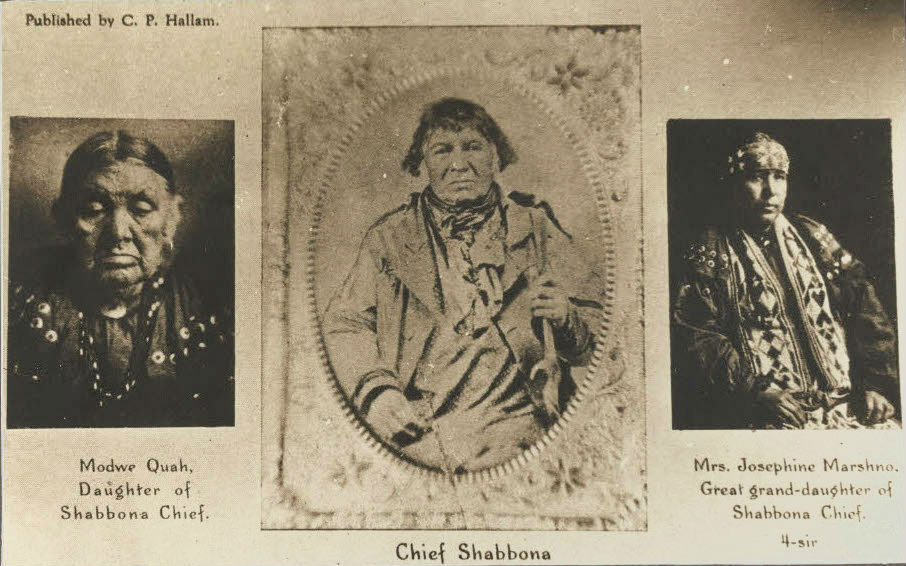

Another Native American name that has long been associated with early Pekin history is that of a Pottawatomi leader named Shabbona, whose name is also spelled Shaubena and Shabonee. He was prominent in the early history of Pekin and Tazewell County and played a significant role in the wider history of Illinois, the Midwest and the U.S. At the time that Jonathan Tharp settled at the future site of Pekin, Shabbona’s camp was in the vicinity of Starved Rock, but Pekin pioneer historian William H. Bates indicates that around 1830 Shabbona and his family had set up a small village of Pottawatomi just south of Tharp’s cabin, between McLean Street and Broadway. But not much later, during the Black Hawk War of 1832 Shabbona and his family were camped in northern Illinois. Here is Bates’ 1870 account of Shabbona’s connection to Pekin:

“The high ground, from the upper end of Pekin Lake to the southern limits of Pekin, was the home of a tribe of Pottawatomie Indians, under the leadership of Shabbona, an able chieftain, who gained the friendship and gratitude of the white pioneers by warnings and tribal protection, for which he was appropriately named ‘The White Man’s Friend.’ In the Indian war of 1832, because he refused to join Black Hawk, in an attempt to exterminate the ‘pale face,’ he had to seek refuge near his white friends in order to save his life.

“Shabbona, and his immediate followers, while in this vicinity, occupied the high ground near our present Gas Works, on what is today Main street, southward to a point near the present C. P. & St. L. [Railway’s] round house. . . .

“Jonathan Tharp was the first permanent white settler in ‘Town Site,’ the date being 1824. He located his crude log cabin near the family wigwams of Shabbona, just west of the present Franklin School.”

Bates’ account is valuable, but is wrong or misleading on just one point: In 1824, Shabbona’s camp was near Starved Rock, not at Pekin, so Tharp could not have built his cabin near Shabbona’s wigwams in 1824. It was apparently about 1830 that Shabbona camped for a season at Pekin near Tharp’s cabin, between Broadway and McLean.

A member of the Ottawa tribe, Shabbona was born about 1775, but his place of birth is uncertain. In his 1879 “History of Tazewell County,” Charles C. Chapman said Shabbona “was born at an Indian village on the Kankakee river, now in Will county,” but others say he was born in Ontario, Canada, or on the Maumee River in Ohio.

Shabbona was a son of Opawana, nephew of the great Ottawa Chief Pontiac, and his father had fought alongside Pontiac in Pontiac’s War of 1763. His name comes from the Ottawa word zhaabne (related to the Pottawatomi word zhabné) which means “hardy” or “indomitable,” and interpreted by white settlers as “built like a bear.” The Ottawa originally lived in Ontario, Canada, but were driven out by the Iroquois, moving to Michigan where they joined with the Ojibwa and Pottawatomi, and afterwards migrating with their kinsmen the Pottawatomi to Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. Around 1800, Shabbona married a daughter of a Pottawatomi chief in Illinois named Spotka (Hanokula), and upon the death of his wife’s father he succeeded him as leader of Spotka’s Pottawatomi band. Shabbona also married Mimikwe or Miomex Zebequa ‘Po-ka-no-ka’ (Coconako), a daughter of Topinabe, a Pottawatomi chief in Michigan. Pokanoka was Shabbona’s chief wife.

Chapman devoted a few pages of his 1879 history to the life of Shabbona, whom he praised as “The kind and generous Shaubena” and “that true and generous hearted chief.” In his account of the Black Hawk War of 1832, Chapman wrote:

“At the time the war broke out he, with his band of Pottawatomies, had their wigwams and camps on the Illinois within the present limits of the city of Pekin. Shaubena was a friend of the white man, and living in this county during those perilous times, and known by so many of the early settlers, that we think he deserves more than a passing mention. . . . While young he was made chief of the band, and went to Shaubena Grove (now in De Kalb county), where they were found in the early settlement of that section. In the war of 1812 Shaubena, with his warriors, joined Tecumseh, was aid to that great chief, and stood by his side when he fell at the battle of the Thames.”

Shabbona’s experiences in the War of 1812 convinced him of the futility of armed resistance to white encroachment, and for the rest of his life he strove to live in peace with the white settlers who were flooding into Illinois. Many Native Americans in Illinois called him “the white man’s friend” – and they didn’t mean it as a compliment.

Together with a fellow Pottawatomi leader named Wabaunsee, Shabbona kept the Pottawatomi out of the 1832 Black Hawk War, despite two attempts of Sauk war leader Black Hawk to persuade him to join the fight. “On one of these occasions,” Chapman wrote, “when Black Hawk was trying to induce him and his band to join them and together make war upon the whites, when with their forces combined they would be an army that would outnumber the trees in the forest, Shaubena wisely replied ‘Aye; but the army of the palefaces would outnumber the leaves upon the trees in the forest.’ While Black Hawk was a prisoner at Jefferson Barracks he said, had it not been for Shaubena the whole Pottawatomie nation would have joined his standard, and he could have continued the war for years.”

About a decade before the Black Hawk War, famed Pottawatomi war chief Senachwine Petchaho (Znajjewan), who at times dwelt at or near Washington, Illinois, had also expressed his conviction that hostile resistance to white encroachment was futile. Chapman quotes from Senachwine’s address to Central Illinois white settlers in which he lamented the decline of his people and mistreatment at the hands of the settlers:

“When you palefaces came to our country we took you in and treated you like brothers. We furnished you with corn and gave you meat that we killed, but you palefaces soon became numerous and began to trample upon our rights, which we attempted to resist, but was whipped and driven off. This is returning evil for good. The graves of my forefathers are just as dear to me as yours, and had I the power I’d wipe you from the face of the earth. I have 800 good warriors, besides many old men and boys, that could be put in a fight, but this takes up a remnant of these tribes since the last war. I believe I could raise enough braves, and taking you by surprise, could clean the State. I know I could go below your capital and take everything clean. But what then? We must all die in time. You would kill us all off. You tell me that you have forbidden your men to sell whisky. You enforce these laws and I stand pledged for any depredation my people shall commit. But you allow your men to come with whisky and trinkets and get them drunk and cheat them out of all their guns and skins and all their blankets, that the Government pays me yearly for this land. This leaves us in a starving freezing condition and we are raising only a few children compared to what we raised in Old Kentuck, before we knew the palefaces. Some of my men say in our consultations, let us rise and wipe the palefaces from the face of the earth. I tell them no, the palefaces are too numerous. I can take every man, woman and child I’ve got and place them in the hollow of my hand and hold them out at arm’s length. But when I want to count you palefaces I must go out in the big prairie, where timber ain’t in sight, and count the spears of grass, and I haven’t then told your numbers.”

The Black Hawk War was the last, desperate attempt of Native Americans living in northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin to resist their displacement before the wave of encroaching white settlers. The war is named for Sauk warrior Black Hawk (Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, 1767-1838), who had refused to accept the treaties with the U.S. by which the Sauk people had agreed to move from Illinois and Wisconsin to Iowa. Black Hawk repeatedly led hunting parties from Iowa into Illinois, and in 1832 when he was ordered to cease his “incursions,” he attempted to forge a confederacy of tribes to resist white settlement. But by 1832 it was already too late for the Indians of Illinois – though the war opened in April 1832 with a victory for Black Hawk caused by American incompetence at Stillman’s Run (in which Pekin co-founder Isaac Perkins was killed), Black Hawk’s efforts were futile and the war was over in months, having been nothing more than an occasion for whites and Indians to commit some brutal massacres upon each other. Black Hawk retreated to Prairie du Chien in Wisconsin, where he surrendered on 27 Aug. 1832 — bringing Illinois’ leaders to the conclusion that all remaining Native Americans should be expelled from the state.

Chapman commented, “To Shaubena many of the early settlers of this county owe the preservation of their lives, for he was ever on the alert to save the whites.” But, Chapman said, “by saving the lives of the whites (he) endangered his own, for the Sacs and Foxes threatened to kill him, and made two attempts to execute his threats. They killed Pypeogee, his son, and Pyps, his nephew, and hunted him down as though he was a wild beast.” After the surrender of Black Hawk, for their alliance with the U.S. Shabbona and Wabaunsee were rejected by their people, who instead chose as their leader Kaltoo, also called Ogh-och-pees, eldest son of the late Pottawatomi war chief Senachwine.

In the immediate aftermath of the Black Hawk War, new treaties were negotiated so Illinois would be cleared of all of its Native American tribes. The Pottawatomi of Indiana and Illinois, including those who had lived at Pekin, were deported to Nebraska and Kansas, and, as we have noted before, the agonizing march of the Indiana bands is remembered as the Pottawatomi Trail of Death. Shabbona, however, was allowed to have a reservation of two sections of land at Shabbona’s Grove. Nevertheless, “by leaving it and going west for a short time the Government declared the reservation forfeited, and sold it the same time as other vacant land. Shaubena finding on his return his possessions gone, was very sad and broken down in spirit, and left the grove for ever,” Chapman wrote.

The people of the town of Ottawa then bought him some land near Seneca in Grundy County, where Shabbona stayed until his death on 17 July 1859. “He was buried with great pomp in the cemetery at Morris,” Chapman wrote. His widow Pokanoka drowned in Mazen Creek, Grundy County, on 30 Nov. 1864, and she was laid by his side. Efforts to raise money for a grave monument were interrupted by the Civil War, so it was not until 1903 that a large inscribed boulder was placed at their final resting place.

According to the 1886 compilation “Abraham Lincoln’s Vocations,” some years later Shabbona’s daughter and her son, John Shabbona, came from the reservation at Mayetta, Kansas, and visited Shabbona’s Grove, viewing photographs and documents pertaining to Shabbona in DeKalb and Chicago. In 1903, when Shabbona’s monument was laid, John Shabbona again returned to Chicago along with members of several of the expelled tribes of Illinois for a special Indian encampment recognizing the original peoples of Chicago (see “City Indian: Native American Activism in Chicago, 1893-1934,” 2015, by Rosalyn R. LaPier, David R. M. Beck, page 64).

As a happy but love-overdue epilogue, after many years of litigation, earlier this year the U.S. Department of the Interior ruled that Shabbona’s land was never legally forfeited, and formally recognized Shabbona’s Grove as a reservation for his people, the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. This is Illinois’ first federally recognized Indian reservation.