It was less than a decade from the creation of the Illinois Territory in 1809 until Illinois entered the Union as the 21st state. During those years, as we saw last time, the nation would go to war once more against Britain – the War of 1812.

Despite some impressive successes in battle, the U.S. soon found that it had bit off more than it could chew – the British sacked and burned down the nation’s capital in 1814, destroying the original White House. In the Old Northwest, Britain and its Native American allies were able to seize parts of Michigan and Illinois and the entirety of Wisconsin (lands then a part of the Illinois Territory) and maintain control until the war’s end. The British Navy also had the U.S. blockaded, ruining the economy.

With the U.S. facing further humiliation and Britain preoccupied with the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, both sides in the war agreed to cease hostilities. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, which the U.S. ratified on Feb. 17, 1815. The treaty called for Britain and the U.S. to restore the territory they had seized from each other – effectively the war ended in a stalemate.

In practical terms, however, the War of 1812 left the U.S. poised to expand further into Native American lands of the Old Northwest. The destruction of Tecumseh’s confederacy in 1813 had brought an end to effective Native American resistance to the encroachment of land-hungry U.S. settlers who had been pouring into Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Although the Treaty of Ghent called for the U.S. to respect the rights and territories of the American Indians, the U.S. never honored that article of the treaty – and Britain, which abandoned its former allies at the negotiating table, did not wish to go to war again to enforce it.

Even with Native American resistance in the Old Northwest effectively neutralized, however, there were still legal and economic obstacles that slowed the settlement of the Illinois Territory. As former Illinois Gov. Edward Dunne explained in his 1933 history of Illinois, “Up to this time (1812) there had been but little immigration unto Illinois. Fear of Indian atrocities was one cause, but the greater and more far-reaching one was the inability of settlers to gain legal title to the land upon which they located.” In the eyes of the law, most of the settlers in Illinois were squatters, since the laws up till then discouraged white incursion in a region that the British king had formerly set aside as an Indian Reserve.

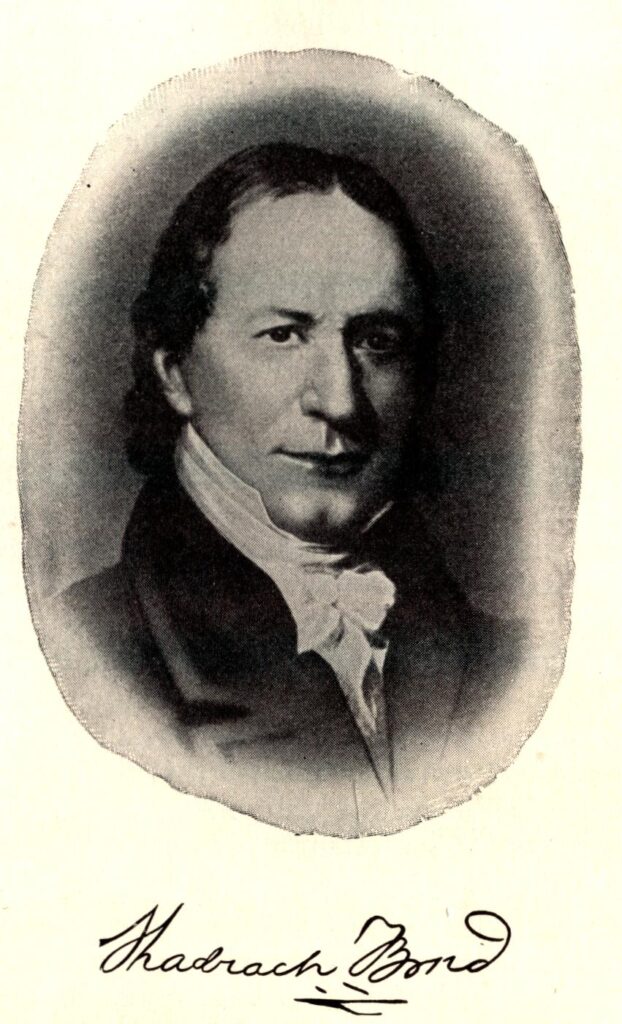

That was soon to change. Dunne wrote, “Shadrach Bond, upon his election as delegate to Congress for Illinois Territory in 1812, exerted himself vigorously in securing a preemption law that would enable a settler to secure a quarter-section of land, and thus attract settlers to the territory.” In 1813 Congress approved Bond’s proposed law, which stipulated that if a settler made improvements to the land he’d secured, then he had the first right to buy that land at government sale.

Due to that law, Illinois soon saw a dramatic influx of settlers. According to Dunne, “The passage of this law, the ending of the war with Great Britain, and the subsequent treaties of peace with the Indians in 1815 under which they conveyed their titles to the United States, opened wide the doors in Illinois for rapid settlement and growth for the first time in its chequered history. From now on the condition of Illinois ceased to be static and became dynamic. Its population in 1810 was 12,282; in 1820 it was 55,162.”

Continuing, Dunne observed, “The dammed-up waters of immigration and civilization had sapped and undermined the walls of war, isolation and law that had surrounded Illinois, and the waves began to overflow the fertile prairies of all the section. Riding on these waves came not only men and women from the Southland, as heretofore, but from all over America and from foreign lands.”

By 1816, editorials were appearing in Daniel Pope Cook’s newspapers, the Kaskaskia Herald and the Western Intelligencer, advocating in favor of Illinois statehood and showing the advantages of self-government that statehood would bring. The chief obstacle to statehood was the Northwest Ordinance’s stipulation that a territory’s population must be at least 60,000 before it could be admitted as a state. Nevertheless, Congress had waived that requirement when it admitted Ohio as a state – and Cook argued that Illinois should be granted the same leniency.

As it happened, the simmering controversy over slavery helped to unite the people of Illinois, both pro- and anti-slavery, in support for statehood. As Dunne explained in his history, support for statehood in Illinois was promoted by the fact that a Congressional bill was already pending for Missouri statehood, and everyone expected Missouri to be a slave state.

“The fear that the Missourians would anticipate the men of Illinois in securing admission of their state into the Union caused prompt action,” Dunne wrote. “The anti-slavery element feared that if Missouri was admitted as a slave-state, that it would be used as a precedent for slavery in Illinois. On the other hand, the pro-slavery element feared the admission of Missouri to statehood before Illinois because, as they believed, it would attract immigration from the South and prevent settlers from coming to Illinois. It developed that both discordant elements, from different motives and activated by different fears, were united in favoring the admission of Illinois to statehood before the pro-slavery crowd in Missouri could secure statehood from Congress.”

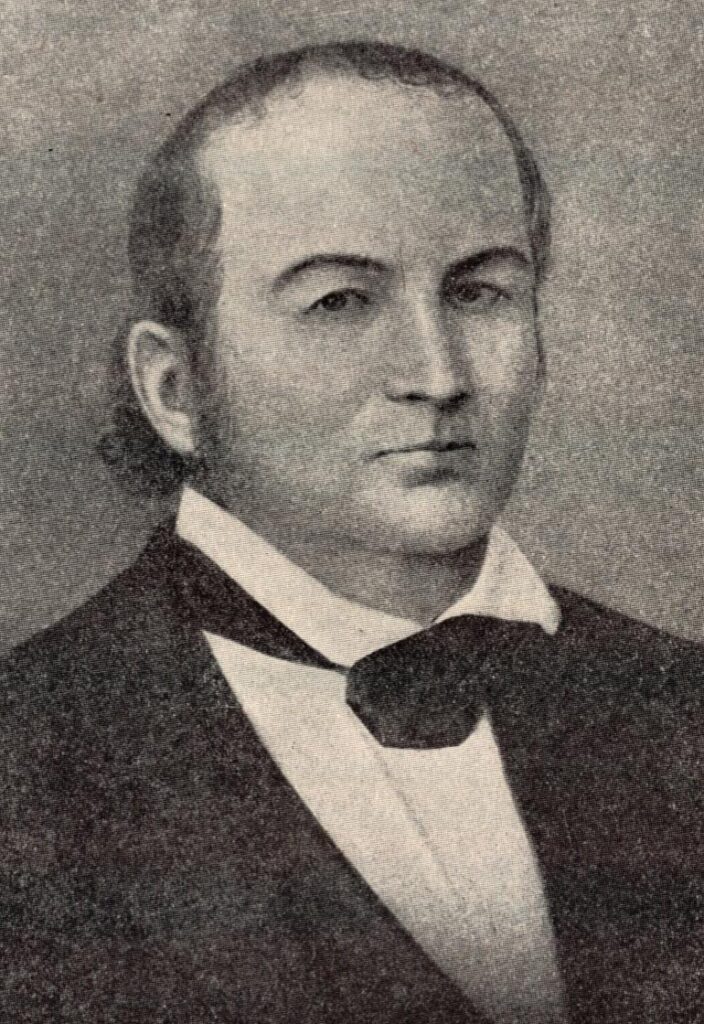

Although Illinois would not become a state until 1818, the bill to admit Illinois to the Union was first introduced in Congress on Jan. 23, 1812, by Illinois’ territorial delegate (and former territorial secretary) Nathaniel Pope (1784-1850). According to Dunne, in its original form the bill would have set Illinois’ northern boundary “at a line drawn east and west from a point drawn ten miles north of the most southerly part of Lake Michigan in an attempt to approach compliance with a provision of the Ordinance of 1787.” That would have given Illinois only a very small amount of Lake Michigan shoreline.

But while the bill was still in committee, Pope had the proposed northern boundary moved 41 miles north, to the position where it is today. The members of the committee accepted the new proposed boundary because it would make the new state more economically viable and, through the Great Lakes system, would firmly link Illinois to New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana. How very different Illinois history would have been if Chicago had instead developed as the largest and wealthiest city of Wisconsin!

On Jan. 16, 1818, the Illinois Territorial Legislature formally petitioned Congress to become a state, sending the petition by the hand of Delegate Pope. The same month, the Legislature, seeking to emphasize to Congress that Illinois would be a free state, approved a bill that would have reformed labor contracts to eliminate the practice of indentured servitude whereby slavery was able to exist in Illinois despite being illegal. However, Gov. Ninian Edwards (1775-1833), himself a wealthy aristocratic slave-owner, vetoed the bill, claiming it was unconstitutional. It was the only time Edwards ever exercised his veto power as territorial governor.

The issue of slavery would remain at the forefront of Illinois political issues in the early years after statehood, as pro-slavery forces strove to legalize it. In anticipation of Illinois’ admission to the Union, the territory framed a state constitution in August – but it is significant that, whereas the Ohio and Indiana state constitutions explicitly forbade any amendments or the writing of new constitutions that would legalize slavery, Illinois’ first constitution had no such provision, a “loophole” of which pro-slavery leaders soon tried to avail themselves.

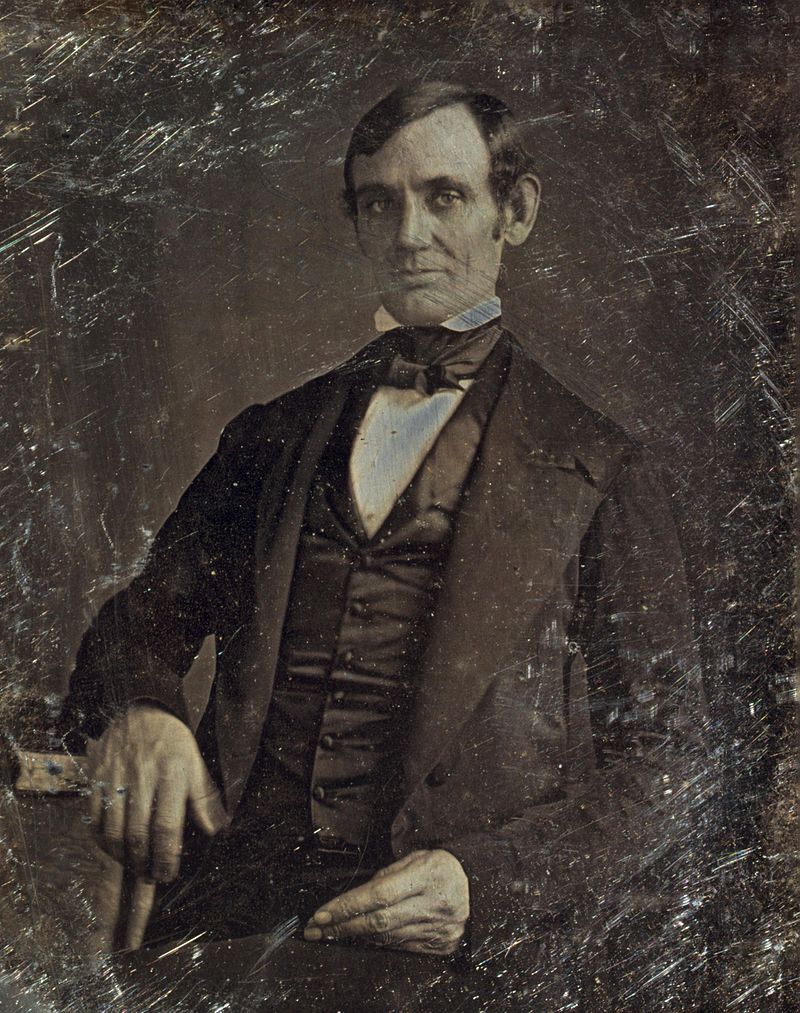

After the ratification of the constitution, Illinois held elections to fill the state offices. Maryland-born Shadrach Bond (1773-1830), former territorial delegate to Congress, was elected the first Illinois governor, taking office on Oct. 6, 1818, about two months before Illinois became a state. The march to statehood proceeded apace throughout the remainder of 1818, until at last, on Dec. 3, 1818, President James Monroe signed the bill granting Illinois admission to the Union as the 21st state. The new state’s population was tabulated in an 1818 census at 40,258.

The territorial capital at Kaskaskia on the Mississippi River now became the first state capital, even as it formerly had been the seat of government reaching back to the days of Virginia’s vast Illinois County during the Revolutionary War. Flooding of the Mississippi led to the removal of the state capital to Vandalia in just two years, however.

At statehood, Illinois already had 15 counties, but within a year four more counties were added. At that time the yet-future Tazewell County’s lands were included in the oversized Bond and Madison counties which then extended all the way to Illinois’ northern border.

The Illinois General Assembly established Tazewell County a mere nine years after statehood. During those years Illinois experienced a rising tide of immigration – and many of those settlers came up the Illinois River or overland from southern Illinois to Fort Clark (Peoria) and its environs. We’ll look closer at that wave of settlement next time.