With the approach of the Juneteenth holiday, it is a fitting time to recall the story of the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry, which was Illinois’ only African-American regiment during the Civil War.

The history of the 29th U.S.C.I. was researched in depth and published in 1998 by military historian Edward A. Miller Jr., whose book, “The Black Civil War Soldiers of Illinois,” is included in the Pekin Public Library’s Local History Room collection.

During the Civil War, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on 1 Jan. 1863. Afterwards, he requested that four regiments of African-American men should be raised. Eventually, 300,000 soldiers in 166 “colored” regiments were raised for the Union Army.

At first, enlistment was slow because of low pay — and because it was expected that captured black soldiers would be badly treated by the Confederacy (as happened at Fort Pillow in Tennessee on 12 April 1864 – about 300 Colored Troops were murdered by the Confederate forces after they had surrendered.)

The War Department set up the Bureau for Colored Troops to determine which white soldiers to commission as officers for the new colored regiments. Non-commissioned officers and privates were African-American. At first there was a stigma attached to being a white officer in a colored regiment, but the prospect of rapid promotion overcame the stigma. Famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass made a visit to Peoria to encourage enlistment in the Colored Troops.

The 29th United States Colored Infantry Regiment was organized at Quincy and mustered into federal service on 24 April 1864. Lieut. Col. John A. Bross of Chicago organized the regiment and became its commanding officer. Bross formerly commanded Co. A of the 88th Illinois Infantry and was a veteran of the Battle of Stones River. His brother was a Chicago Tribune newspaper editor who later became lieutenant governor of Illinois. Because of his political connections, Bross endured mockery as not being a real soldier.

Ten companies were organized: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, and K. The original captain of Co. B was Hector H. Aiken and the original captain of Co. G. was William A. Southwell.

In brief, the history of the 29th U.S.C.I. was: 1) Ordered to Annapolis, Maryland, 27 May 1864, and from there to Alexandria, Virginia; 2) Attached to the defenses of Washington, D.C., 22nd Corps, until June 1864; 3) 2nd Brigade, 4th Division, 9th Corps, Army of the Potomac, until Sept. 1864; 4) 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 9th Corps until Dec. 1864; and 5) 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, 25th Corps, and Dept. of Texas, until Nov. 1865.

Here is a more detailed service record and list of the 29th U.S.C.I.’s battles and engagements:

- Duty at Alexandria, Virginia, till 15 June 1864. Moved to White House, Virginia, thence to Petersburg, Virginia.

- Siege operations against Petersburg and Richmond 19 June 1864 to 3 April 1865.

- Explosion, Petersburg, 30 July 1864 – Battle of the Crater, a debacle with Union losses of 504 killed, 1,881 wounded, 1,413 missing or captured; Lieut. Col. Bross and Capt. Hector Aiken were both killed. The 29th U.S.C.I. alone suffered two officers and 38 enlisted men killed, four officers and 53 enlisted men wounded, and 33 enlisted men captured.

- Weldon Railroad, Aug. 18-21.

- Poplar Grove Church, Sept. 29-30, and Oct. 1.

- Hatcher’s Run, Oct. 27-28.

- On the Bermuda Hundred front and before Richmond till April 1865.

- Appomattox Campaign March 28-April 9. Present at the Surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee.

- Duty in the Dept. of Virginia till May.

- Moved to Dept. of Texas May and June, and duty on the Rio Grande till November.

- Mustered out 6 Nov. 1865.

The regiment lost during its service three officers and 43 enlisted men who were killed and mortally wounded and 188 enlisted men by disease – for a total of 234.

One of the most remarkable episodes in this regiment’s history is that it was present at the first Juneteenth. How that came about is that after Lee’s surrender, the South in general, and Texas in particular, needed occupational forces. Union soldiers were eager to go home, but many in the Colored Troops were willing to stay on the payroll.

Gen. Meigs, quartermaster, still had over 3,000 supply ships, so he put to sea the largest amphibious operation of the war, sending 30,000 troops of the 13th and 25th Corps to the Rio Grande. The port of Galveston surrendered June 5. The 28th Indiana, 29th Illinois, and the 31st New York units of the 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division USCT arrived at Galveston Bay on June 18.

The white units of 34th Iowa, 83rd and 114th Ohio and 94th Illinois all arrived within a few days. Over 6,000 men landed within a week, and the racial makeup of the soldiers in Galveston on Juneteenth 1865 was about half black and half white.

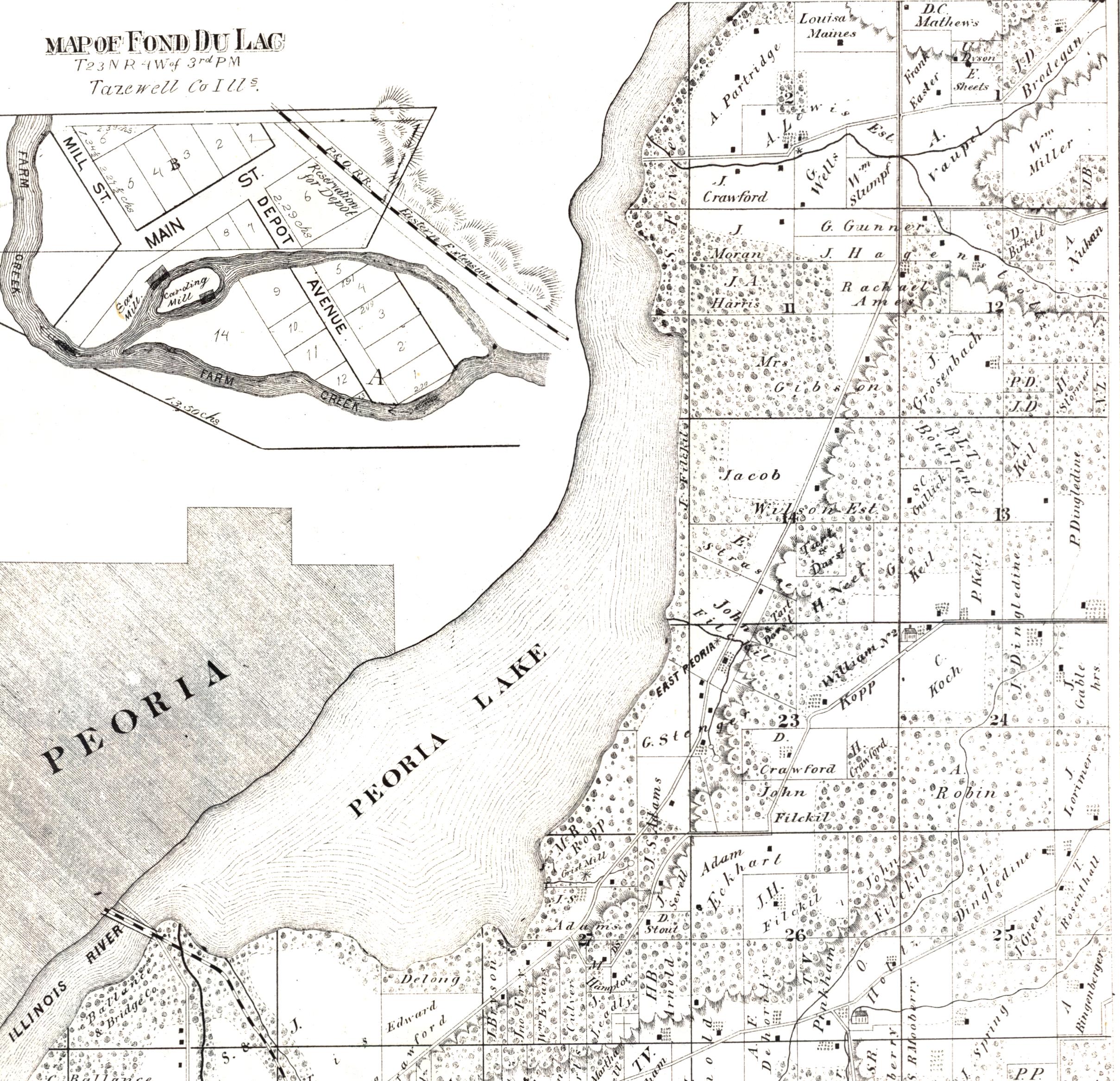

Pekin and Tazewell County provided 11 men to the 29th U.S.C.I., five of whom were present at Juneteenth. Those men are listed below, with the names of the Juneteenth eyewitnesses in boldface:

- William Henry Costley, son of Benjamin and Nance Costley, of Pekin, Co. B

- Edward W. Lewis, of Peoria, formerly of Pekin (married Bill Costley’s sister Amanda in Pekin in 1858), unassigned (served as an Army cook).

- William Henry Ashby, of Pekin, Co. G

- Marshall Ashby, of Pekin, Co. G

- Nathan Ashby, of Pekin, Co. G

- William J. Ashby, of Pekin, Co. G, fell sick 27 March 1865, in hospital most of the rest of his term of service, mustered out 6 Nov. 1865.

- Thomas Shipman, of Pekin, Co. D, a sharpshooter, killed in the line of duty 31 March 1865 during the Appomattox Campaign. (Miller, p.148, says Shipman was killed 30 March 1865, but his service file says 31 March.)

- George H. Hall, of Pekin, Co. B, fell sick 18 May 1865, in hospital most of the rest of his term of service, mustered out 6 Nov. 1865.

- Wilson Price, of Elm Grove Township, enlisted in 29th U.S. Colored Infantry on 30 Sept. 1864, but for an unstated reason at the muster that day he was not taken into the regiment.

- Thomas M. Tumbleson, of Elm Grove Township, Co. B, discharged 30 Sept. 1865 at Ringgold Barracks, Rio Grande, Texas.

- Morgan Day, of Elm Grove Township, Co. G, fell sick 27 March 1865, died of dysentery 6 Sept. 1865 in New Orleans, buried in Chalmette National Cemetery, Louisiana.

The four Ashby men from Pekin are mentioned by Miller on p.118 of his book. Morgan Day was an uncle of most of the Ashby men of Pekin through his mother Rachel. Thomas Shipman also was related to the Ashbys through his brother David Shipman’s marriage to Elizabeth Ashby, who was very probably a sister of Nathan Ashby. Miller again mentions Nathan Ashby on p.201, where he describes Nathan’s life after the war:

“Pvt. Nathan Ashby, one of several solders of that family from Peoria County, Illinois, was living largely on the pension he received in 1892 for rheumatism and lung disease. In a normal review by doctors employed by the pension bureau, his pension was discontinued in 1895 because Ashby was found to be able to perform manual labor. Although restored on appeal, Ashby suffered much without the income, and, when he died in 1899, he left his wife ‘two old mules’ and no other property.”

As related in previous posts here, the Ashby family was from Fulton County but later moved to Tazewell and Peoria counties. Nathan himself moved from Pekin to Bartonville, and was buried in the defunct Moffatt Cemetery in Peoria. As Miller tells in his book, Nathan Ashby’s hard life of poverty after the war was shared by almost all of his fellow soldiers of the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry.