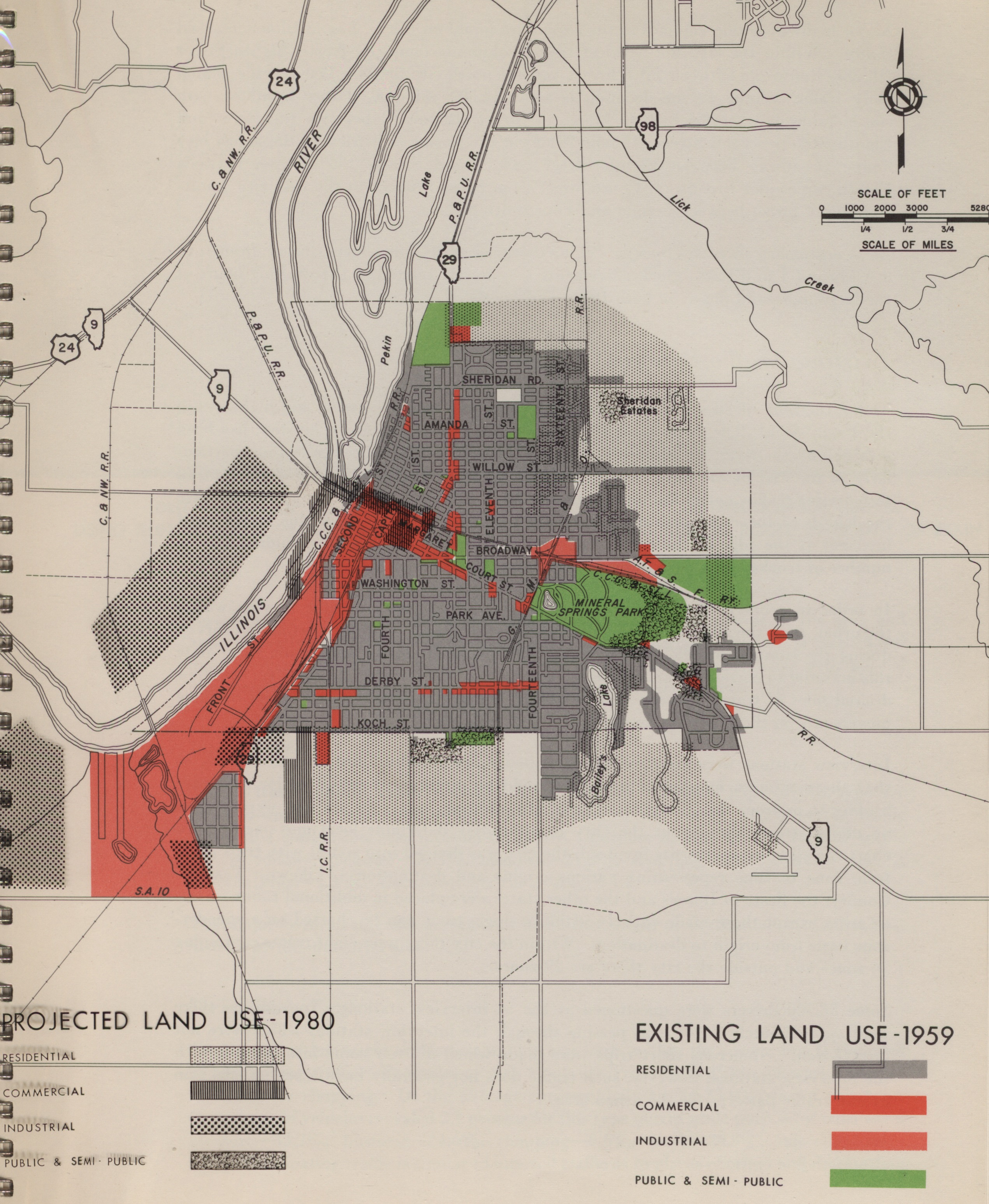

Imagine the city of Pekin in 1980: The post-World War II Baby Boom had continued unabated throughout the 1960s and 1970s, causing Pekin’s population to soar to 45,000 souls. The city doesn’t feel at all crowded, though, and traffic flows smoothly and uninterruptedly from one end of town to the other along one of Pekin’s wide thoroughfares. Drivers crossing the Illinois River have their choice of either the Margaret Street bridge to downtown or the new four-lane Charlotte Street high bridge to the other parts of town.

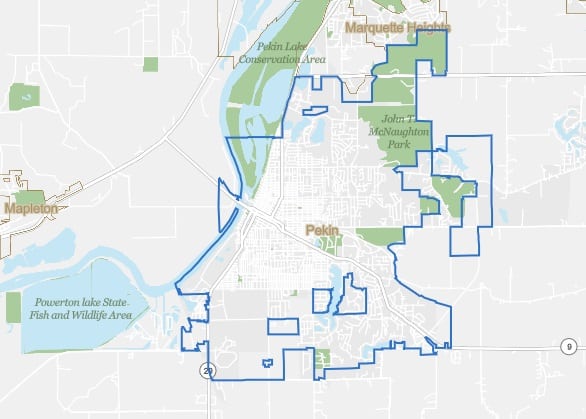

That, of course, was not the real city of Pekin in 1980. The Baby Boom did not continue through the end of the 1980s, but ended in the mid-1960s as a result of drastic changes in American culture and mores spurred by the ready availability of contraceptives. That and economic factors caused Pekin’s population to increase only to about 34,000 in 1980. Nor did drivers in Pekin generally experience smooth traffic flow in 1980, especially with its many railroad crossings and its 1930 lift bridge – and there was (and still is) no four-lane high bridge at Charlotte Street.

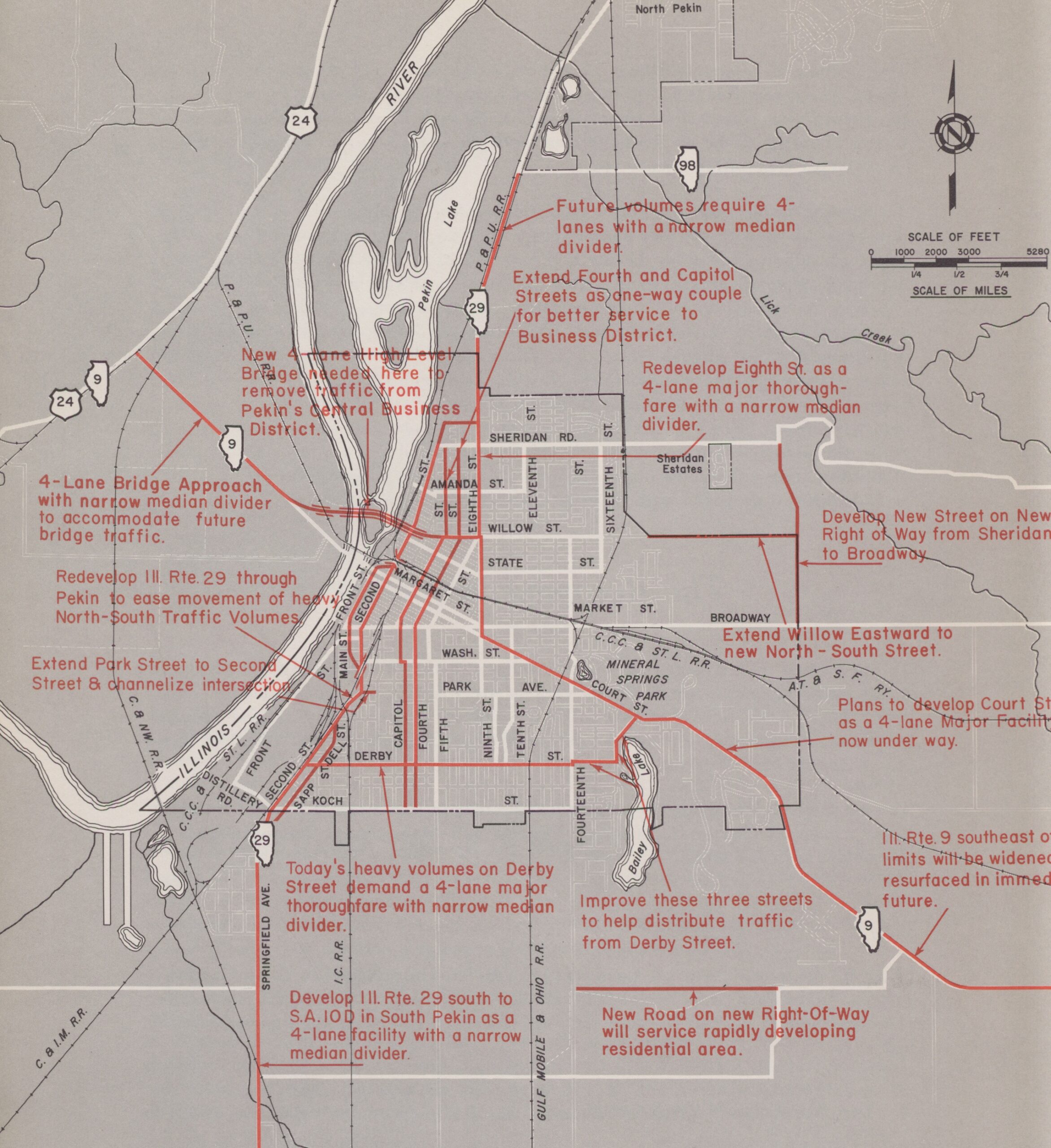

Nevertheless, that was the Pekin in 1980 forecasted in a 1959 street and highway plan prepared by the H. W. Lochner Co. of Chicago for the Illinois Department of Public Works and Buildings’ Division of Highways in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Public Roads (both agencies later being succeeded at the state and federal levels by Departments of Transportation).

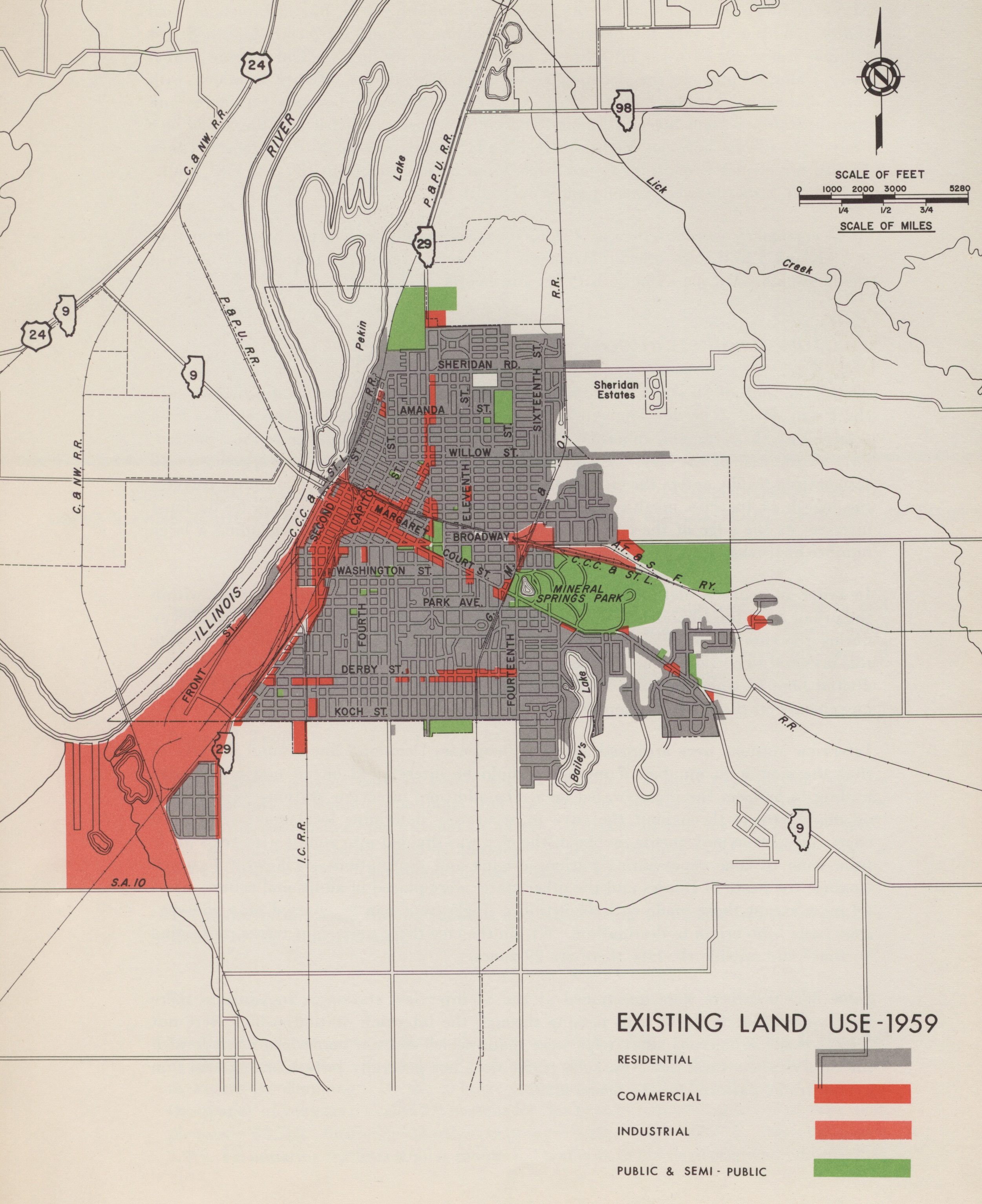

A copy of this 23-page traffic and roadway study, entitled, “A Street and Highway Plan for the Pekin Urban Area,” published in Oct. 1959, and including six large and detailed fold-out maps, is one of the items in the Pekin Public Library’s Local History Archive. The library’s archival copy was once the property of William U. York (1914-1985), a Commonwealth Edison engineer who served as Commissioner for Public Health & Safety on the Pekin City Council, and was formerly stored at Pekin’s old city hall at the corner of Fourth and Margaret streets.

The purpose of the 1959 Lochner study was to analyze Pekin’s then-existing and anticipated street and highway needs over the next two decades. The study identified several impediments to efficient street traffic movement in Pekin, including the fact that Pekin had only a single two-lane lift bridge crossing the river at Pekin’s downtown, slowing traffic in the historic downtown area.

Another problem the study cited was Pekin’s old status as a railway hub – even in 1959, Pekin still had eight railroads that were in daily use, and the town’s complete lack of railroad grade separations (bridges and tunnels) caused drivers many delays as they navigated Pekin’s streets from one end of town to the other. A third problem the study identified was Pekin’s street patterns – not only the infamous discontinuity between the streets of Pekin’s Old Town (perpendicular with the river) and the streets of the rest of town (a north-south-east-west grid), but also that not a single street in Pekin continued uninterruptedly all the way across town.

A survey of the Lochner study shows an extended 20-year vision of improvements for Pekin’s streets and roads, and it is fascinating to consider the 1959 proposals in comparison to what in fact came about.

Obviously the four-lane Charlotte Street high bridge over Cooper’s Island never happened, but the old 1930 lift bridge at Margaret Street was replaced in the early 1980s by a new four-lane high bridge, the John T. McNaughton Bridge. The proposed new bridge would have transformed Charlotte and Willow streets into a major four-lane artery that would have facilitated traffic out to the east end of town and to a widened 14th Street.

The plan also recommended the creation of a new north-south street out on the eastern edge of town that would connect Broadway with Sheridan at the point where Rainbow Drive is today. That part of the plan was partly realized, but in a different form – instead of placing the new north-south street that far east, Parkway Drive was created in stages, extending from Court Street north to Edgewater Drive (Route 98).

The 1959 plan did not foresee the Veterans Drive “Ring Road” concept, but there is a comparable proposal in the plan: widening and extending what is today the Veterans Drive/Court Street intersection along Mall Road straight west to South 14th Street. That would have cut across what later became Sunset Hills Lake No. 2, which did not exist yet in 1959. The Lochner study also did not anticipate or recommend the renumbering of Veterans Drive as Route 9 instead of Court Street.

One of the plan’s recommendations was implemented almost to the letter: redesignating Capitol and Fourth Streets as alternating north-south one-way streets in order to facilitate movement of traffic to and from the downtown and Derby Street commercial districts. One of the study’s recommendations – an upgrade and widening of Derby Street with the addition of center medians – has only begun to be implemented within the past two years or so. The study also recommended several improvements and widening projects of Court Street that were implemented years ago.

One of the guiding principles of the 1959 Lochner study was that traffic flow needed to be directed away from, around, or past Pekin’s downtown to prevent traffic jams there. To that end, the study recommended major changes to Illinois Route 29 to enable north-south traffic to and through Pekin to bypass the downtown area. The revamped Route 29 would have veered off to the west at Coolidge and Lakeside Cemetery, then would have followed a four-lane Second Street under the new Chestnut Street high bridge, under the downtown railroad junctions and Washington Street crossing, and then south out of town and on to Springfield.

In total, the 1959 street and highway plan proposed 17 major street improvements to be funded variously by the city, county, state, and federal government and implemented over the course of 20 years – and all at the low, low cost estimate of $15,480,00 (a figure that would have been unrealistic even in 1959, let alone 1980 or today). Considering how ambitious the Lochner study’s proposals are, it is no wonder that so few of the recommendations were adopted by the Pekin City Council, and how gradually the city has implemented those recommendations that it did adopt.

Also, in retrospect it can be said that, while the goal of trying to keep downtown’s streets from being overcrowded with automobiles was a sensible one, the Lochner study could not anticipate the development of the East Court commercial district and the severely deleterious effect that it, and the intentional bypassing of downtown, would have on Pekin’s downtown businesses during the 1970s and 1980s.