In this week’s installment of this retelling of the story of Betty E. Crabb’s death, we turn to an account of the coroner’s inquest that was held to determine the cause and manner of her death.

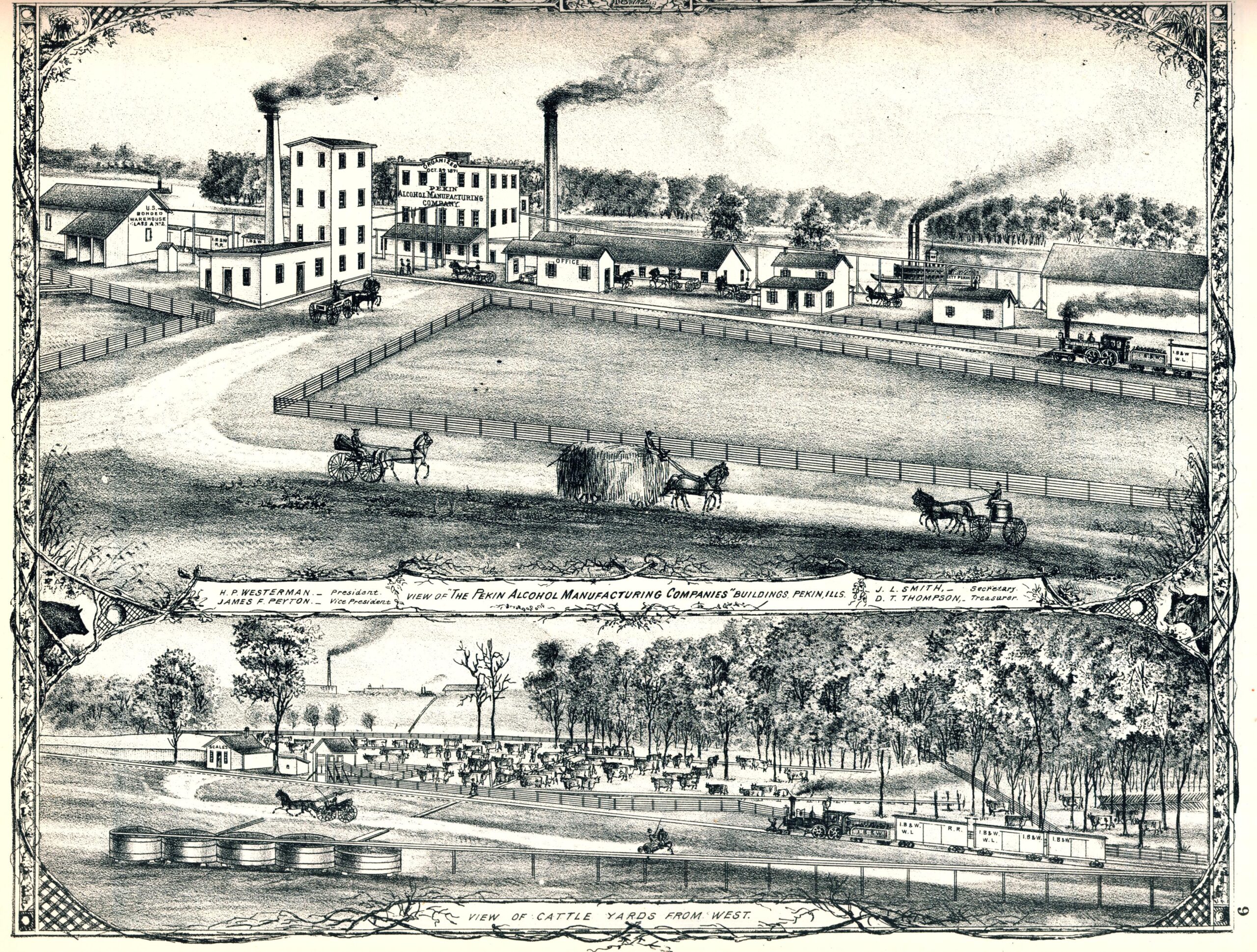

As mentioned in a previous installment in this series, Tazewell County Coroner Dr. Nelson A. Wright II convened the inquest at Houghton’s funeral parlor in Delavan on Wednesday, 8 March 1938. The jurors were W. W. Alexander (the jury foreman), Delavan Police Chief Joe Cook, Richard Yarrington, Gerald Warne, Joe Sowa, and Howard Alexander. Due to the extensive amounts of testimony and evidence at the inquest, the proceedings of the inquest took up four days.

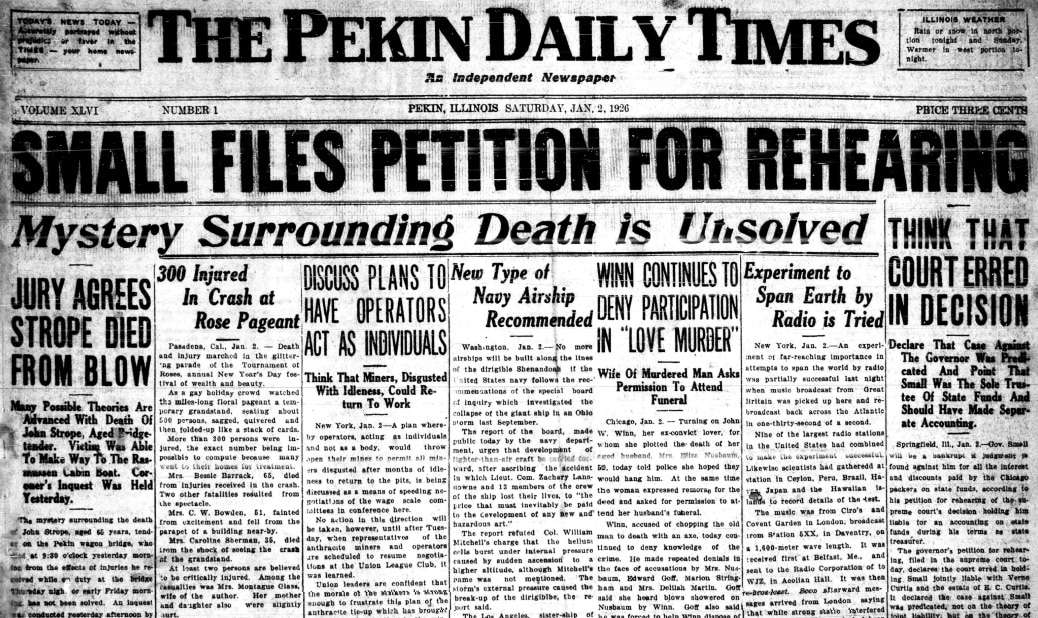

On account of the shocking circumstances of Betty’s death, the inquest attracted large crowds of the curious who packed the funeral parlor or stood outside. Newspapers in the area and from further abroad sent reporters who provided an intense and unusually detailed coverage of the story. In particular, the Pekin Daily Times published complete transcripts of each day’s testimony, something that was made possible because the Times’ reporter assigned to this story was a trained stenographer.

The general circumstances of Betty’s death were clear enough: after returning home late from a party where Betty and Jimmie Crabb got drunk, Betty suffered a single, fatal gunshot, the bullet fired from her husband’s Colt .45 pistol. Her husband Jimmie claimed that she shot herself.

Was it a suicide, a terrible accident, or had Jimmie murdered his wife of five weeks? The coroner’s jury impaneled for the inquest was tasked with examining the evidence and issuing a verdict on the cause and manner of Betty’s death.

Unquestionably, the moments of the inquest that drew the greatest attention from the news media and the public were when Jimmie Crabb was called to testify under oath.

And Jimmie was called to testify twice!

The four most crucial things that came out at the inquest were:

- Betty was not depressed nor had ever expressed a desire to kill herself. When asked if she knew why Betty might want to kill herself, Jimmie’s step-mother Catherine Crabb said only that Betty had once confided in her, “This is my third time to be married, and if this one don’t work, I won’t have any place to go.”

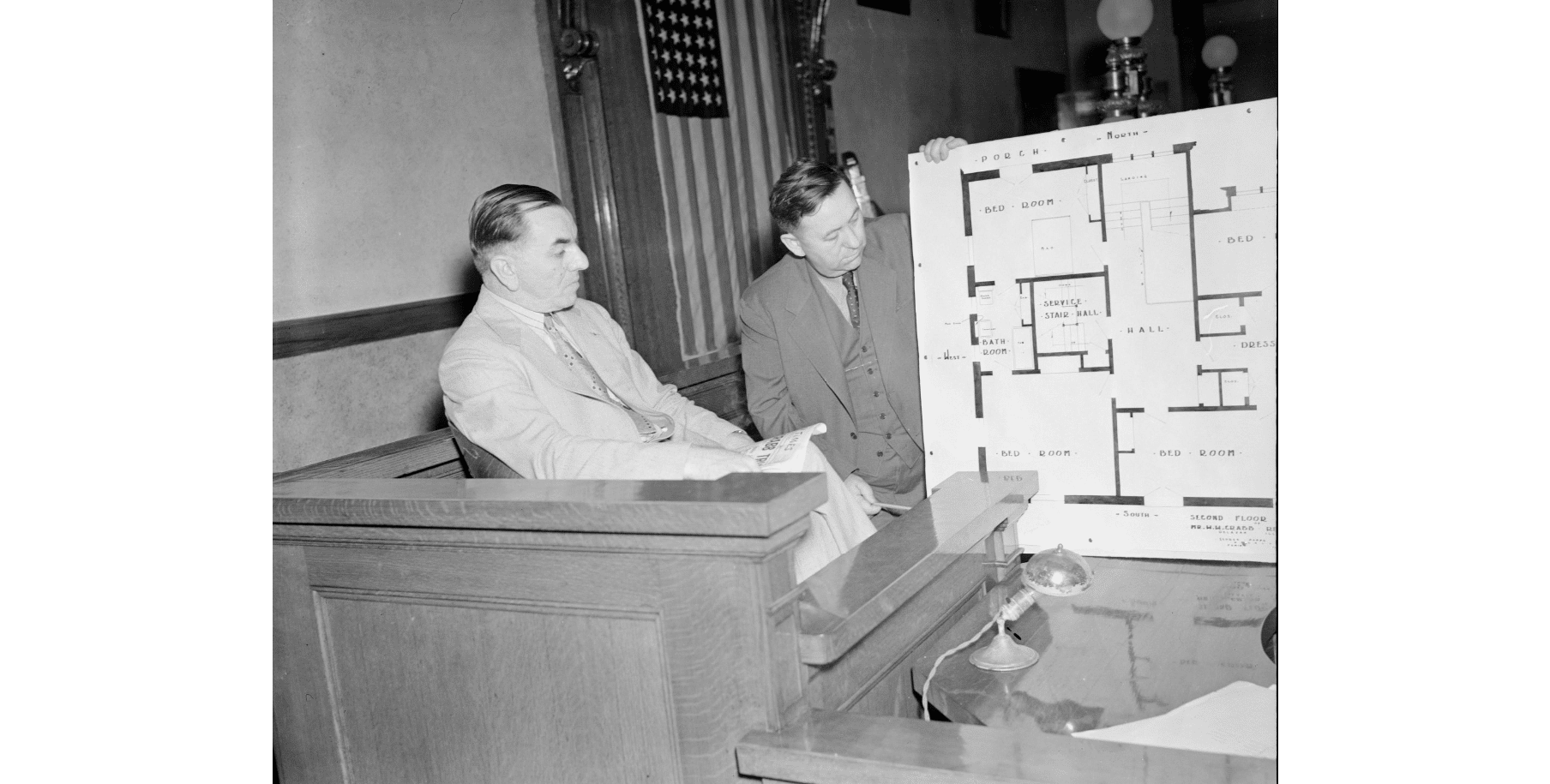

- Officer Ringo told the jury that Jimmie was alone in the bedroom after the doctor was called for up to 10 minutes – long enough to alter the death scene.

- Coroner Wright revealed that the autopsy showed Betty’s stomach was empty. But Jimmie had testified that he and she had shared a sandwich minutes before the shooting.

- The biggest bombshell of the inquest: Tazewell County Sheriff Ralph Goar testified, “It would be utterly impossible for me to point this gun at my right breast and pull the trigger.”

Overall, the testimony of Jimmie Crabb, his father, and step-mother tried to reinforce Jimmie’s claim that it was Betty who had used the gun on herself, and tended to downplay Jimmie’s “rampage” that had led his father to call the police and ask Police Chief Cook to come to the house. The Crabbs also brought their attorneys, who treated the inquest as if it were a criminal or civil proceeding rather than a process to ascertain the circumstances and manner of a death to be recorded on Betty’s death certificate.

However, many facts brought out during the inquest revealed serious inconsistencies and problems with Jimmie’s story. For that reason, Coroner Wright called Jimmie back to the stand, to give him a chance to retract and change his testimony.

As for Jimmie’s in-laws, Glenn and Hazel Collison, they were sure Jimmie had murdered his daughter, and were very concerned that the wealthy Banking Crabbs of Delavan didn’t enable Jimmie to escape responsibility.

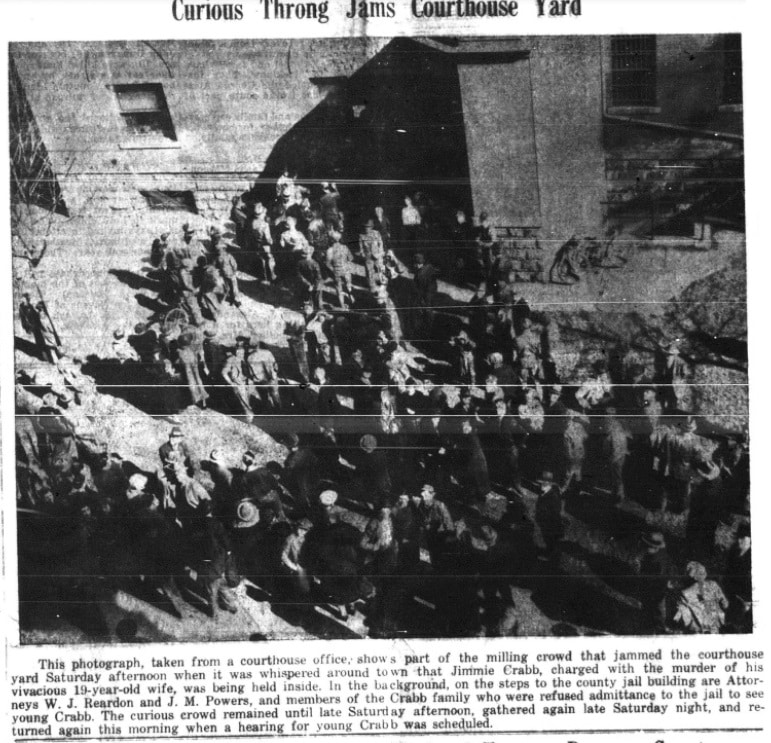

Before the inquest had ended, Glenn Collison swore out a warrant for Jimmie’s arrest for murder. On Saturday, 12 March 1938, after Jimmie completed his second round of inquest testimony, Sheriff Goar served the murder warrant and took Jimmie to the Tazewell County Jail in Pekin for questioning.

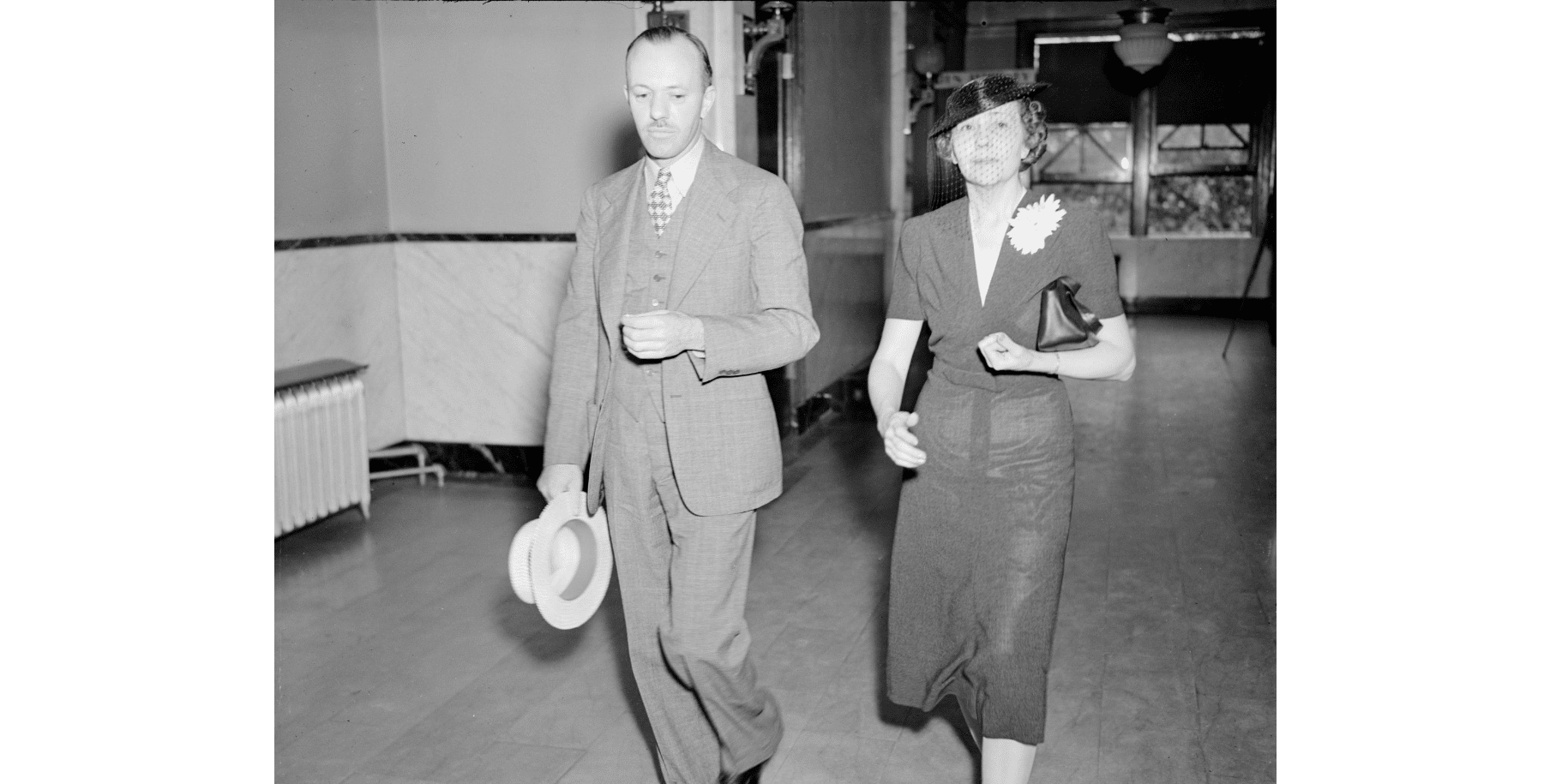

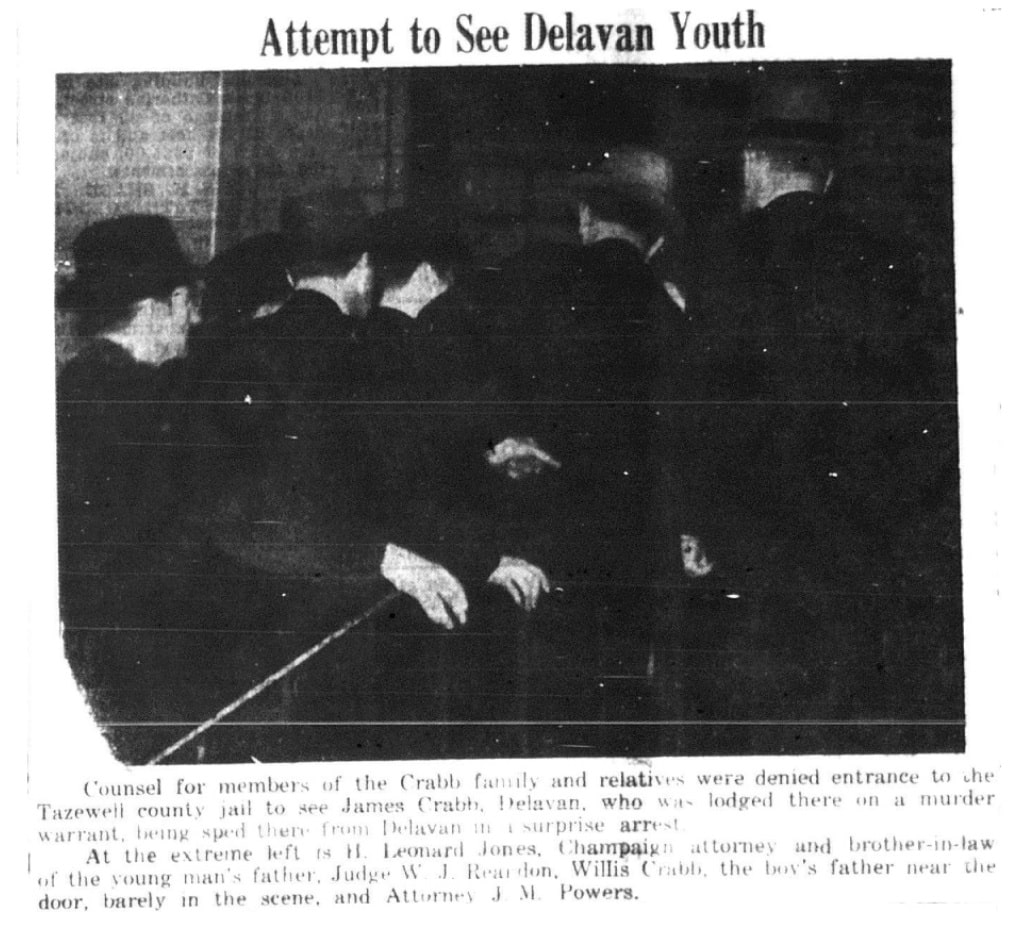

The Crabbs’ attorneys, J. M. Powers, William J. Reardon Sr., and Champaign attorney H. Leonard Jones, along with Jimmie’s father W. W. Crabb, then left the inquest in Delavan and drove to Pekin – and were soon followed by many of the inquest’s spectator from Delavan.

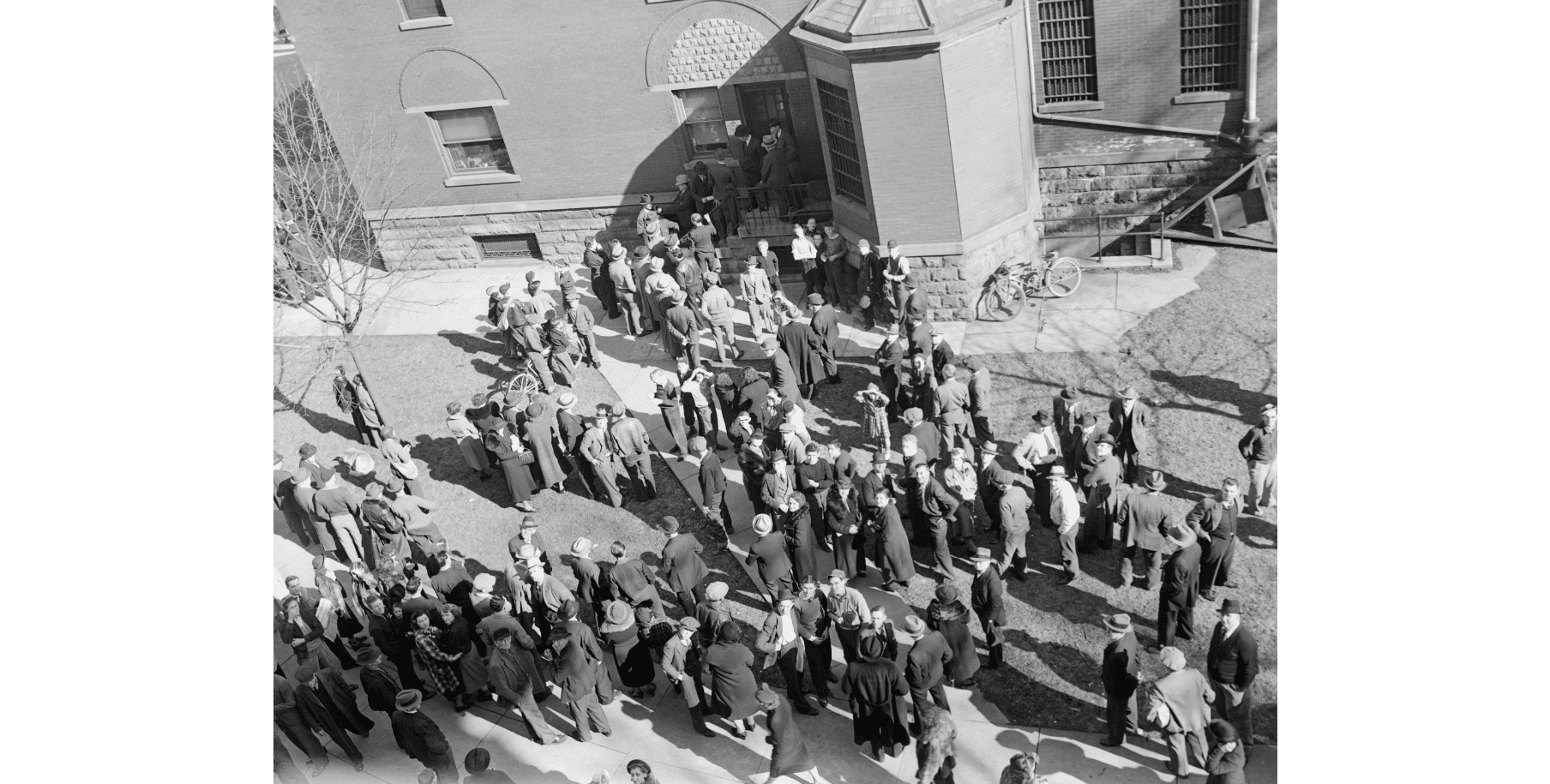

Soon a large crowd was milling about outside the jail, while Jones, Reardon, Powers, and Jimmie’s father stood at the jail’s side door insisting that they be admitted while the sheriff and other deputies interrogated Jimmie. When they were refused entry, the attorneys went to the courthouse to file a writ of habeas corpus.

Meanwhile, the inquest jury came back from their deliberations with an open verdict. The jury could not decide whether Betty’s death was a suicide, an accident, or a homicide, and they asked for further investigation into her death. The jurors, announcing to the press that they were glad the four-day grueling inquest was over, stood proudly and with beaming smiles for the reporters’ cameras.

After a few hours of questioning, Sheriff Goar obtained a statement from Jimmie Crabb in which he changed his story. No longer claiming that Betty had shot herself, Jimmie now said he got into an argument with his father, the conflict escalating due to his drunkenness to the point that Jimmie pick up his gun and pointed it at his father. Willis Crabb then called the police, and Jimmie went back to his bedroom, still waving his gun. Betty, he said in his statement, pleaded with him to put the gun down. When she reached for the gun to push it away, the gun accidentally went off. Jimmie also admitted wiping his fingerprints off the gun and concealing it between the mattress and headboard, and removing the pillow underneath Betty’s head to make her more comfortable.

But Jimmie refused to sign the statement.

Next week we will tell of Jimmie’s indictment and trial for killing his wife.