In this series on the death of Betty E. Crabb of Delavan, we have told of the devastating aftermath of her tragic death. Despite two criminal trials that sought to hold Betty’s husband James W. Crabb II responsible for her death, neither trial seemed to deliver justice for Betty’s family.

Although Jimmie Crabb never served any time for Betty’s death, still it can be said that he paid dearly for his awful alcohol-fueled rampage that ended with his wife dead at the end of his own pistol. He may have escaped prison, but the consequences of his actions cast a dark shadow over his life, and played a significant role in the Fall of the House of Crabb.

As we saw last time, Jimmie Crabb’s 1 Oct. 1938 perjury conviction was overturned by the Illinois Supreme Court on 10 Oct. 1939, bringing Jimmie some measure of relief for him in all his self-inflicted troubles.

But by this time, Jimmie’s father Warren Willis Crabb was himself paying for his own misdeeds. Throughout 1938, W. W. Crabb, intent on keeping his son out of prison, shouldered the great financial burden of his son’s legal troubles. The first hint that Jimmie’s legal bills could be jeopardizing the Crabbs’ wealth was the dispute Willis had with his attorney J. M. Powers after Jimmie’s manslaughter trial, over the fees Powers was charging.

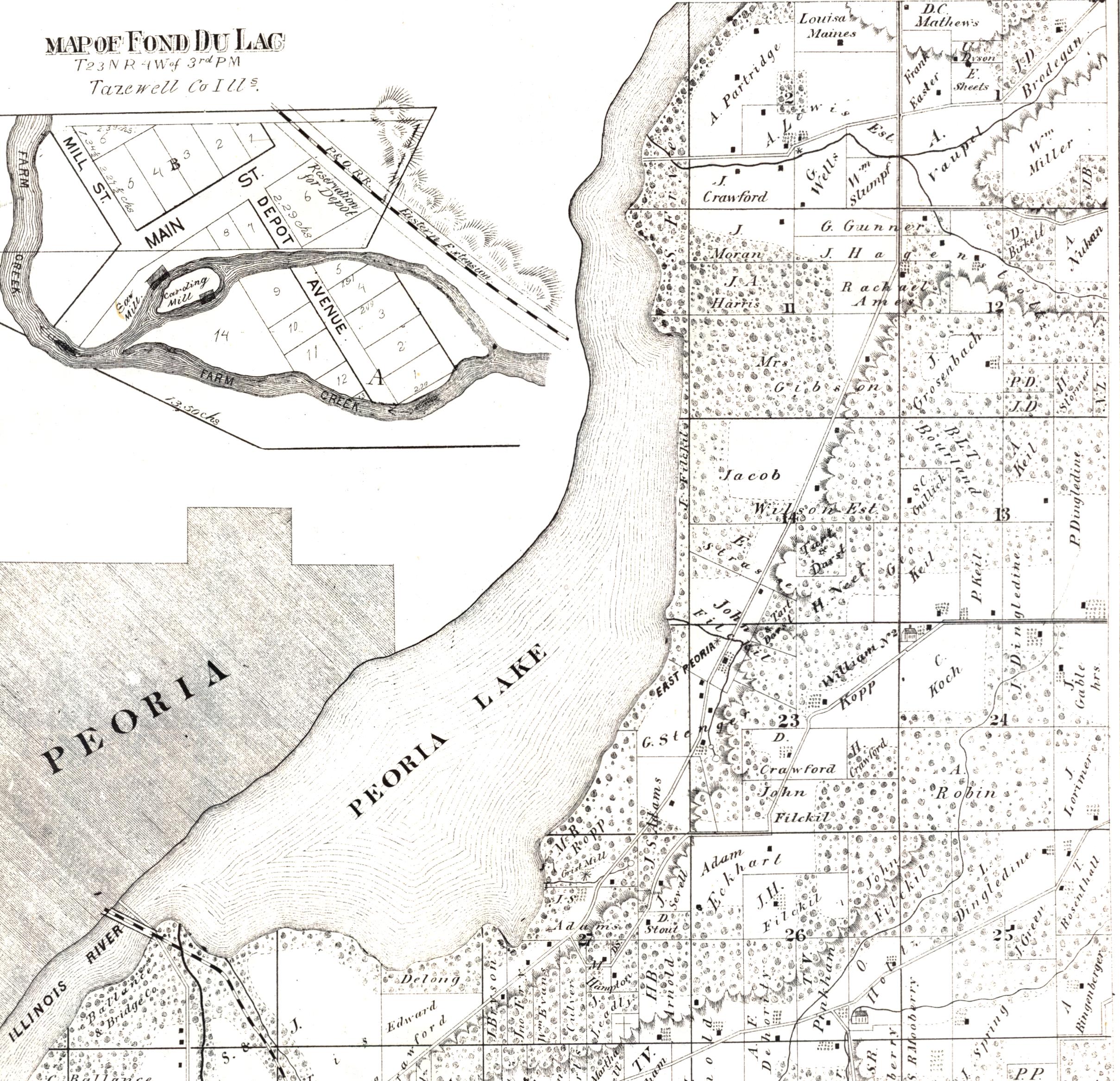

But when word got out that federal bank examiners were looking into the operations of Delavan’s Tazewell County National Bank, of which W. W. Crabb was head, it soon became apparent that Willis’ scandalous divorce and remarriage and Betty’s death were not the only reasons to believe that all was not right with the House of Crabb.

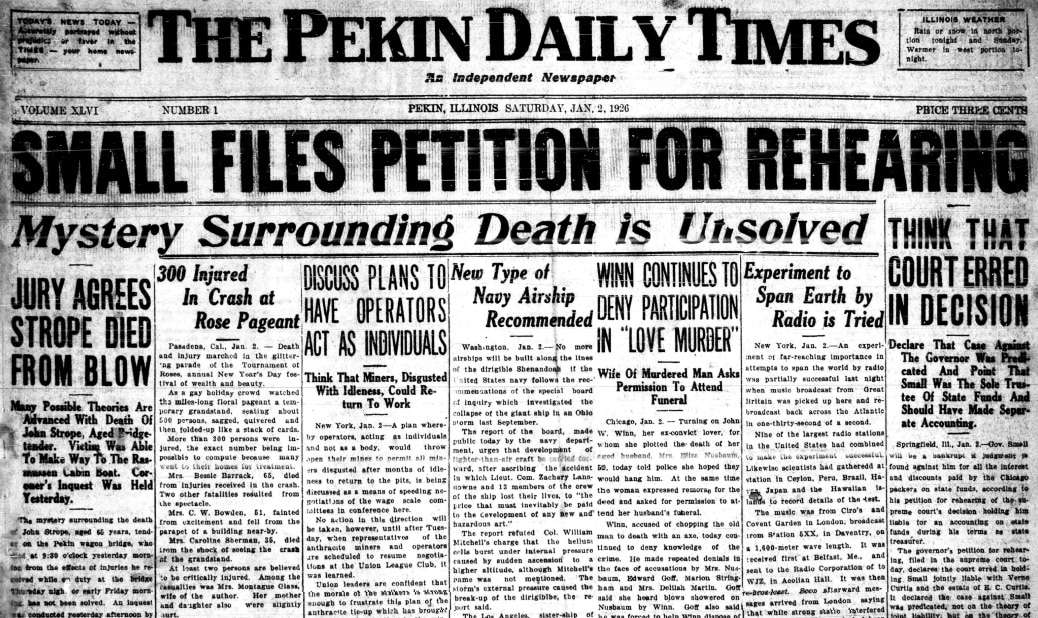

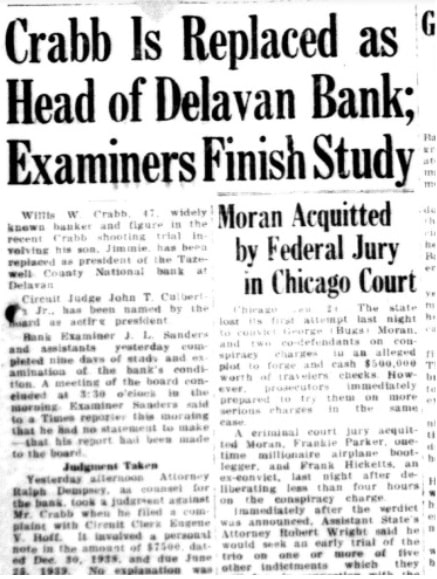

The latest storm in the Crabbs’ lives broke on 21 Jan. 1939, when the Pekin Daily Times ran a story with this headline:

“Crabb Is Replaced as Head of Delavan Bank; Examiners Finish Study”

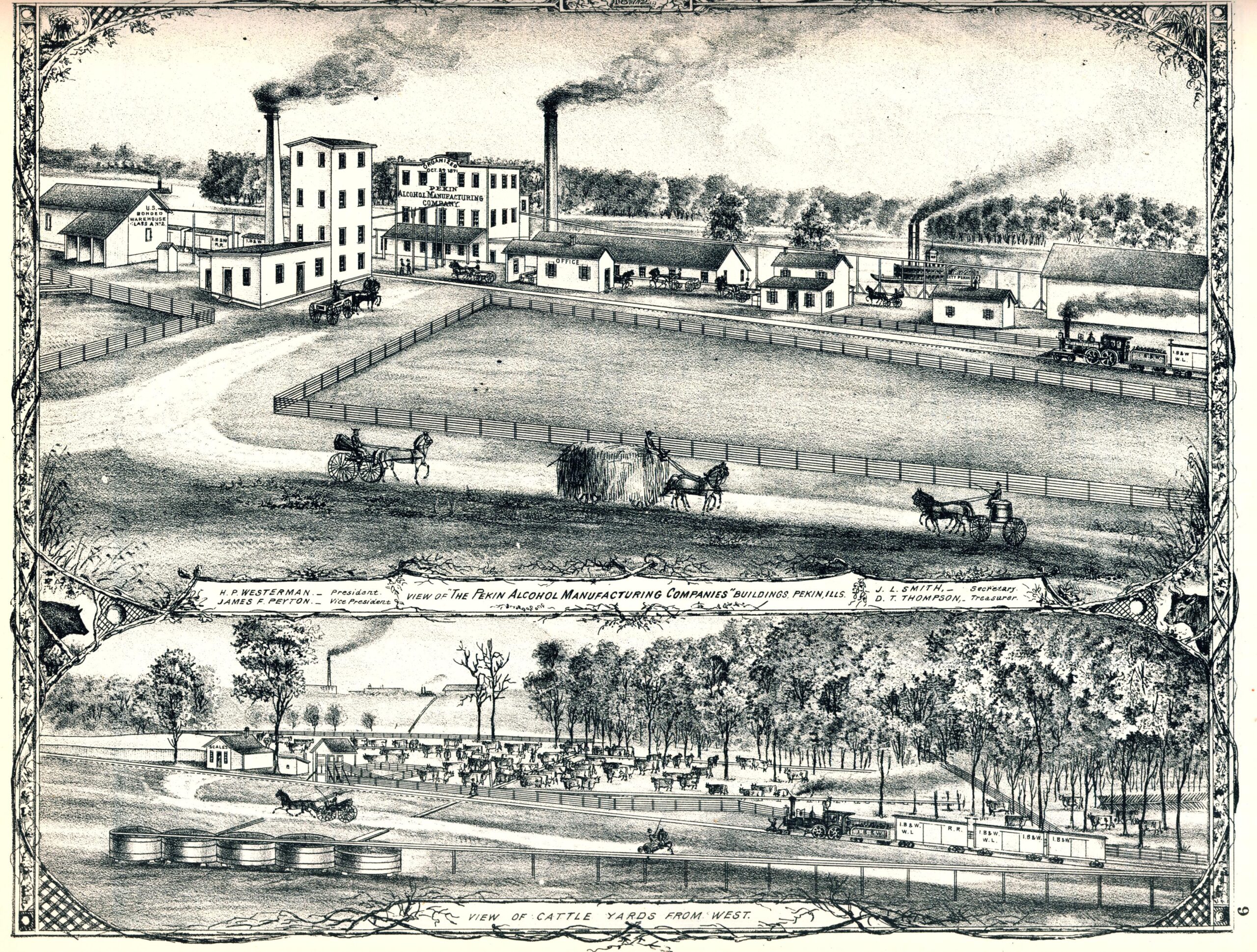

That headline heralded the fall of the Banking Crabbs of Delavan. It turns out that as early as 1934 – four years before Betty’s death – Willis Crabb and a prominent Delavan cattle buyer, James Bailey, had cooked up a scheme to acquire money for a Southern Illinois oil business investment.

Using his position as head of the bank, Crabb forged mortgage papers for loans to people who didn’t know they have borrowed money from the bank. Crabb’s forgeries cost his bank $23,109.91 – but his son’s legal bills in 1938 severely depleted his wealth, both from his legitimate income and his ill-gotten gains.

The evidence of Crabb’s and Bailey’s wrongdoing that federal investigators had uncovered was undeniable – and so, as the 18 Feb. 1939 Pekin Daily Times reported, Crabb entered a nola contendere plea (i.e., not a guilty plea per se, but a statement that he did not dispute that the government would convict him in a trial).

To pay back the money he had fraudulently obtained, Crabb had to sell the Crabb Mansion. The man who bought it, Judge John Culbertson, had already been appointed head of the Tazewell County National Bank – he got Willis Crabbs’ job and house.

Crabb’s attorney appealed to the sympathy of the court by arguing that Crabb was not in the best of health, and had only resorted to his scheme to get money to pay his son’s legal bills (though the scheme was hatched four years prior). Whether that sympathy plea worked or not, Crabb was sentenced to two concurrent four-year terms in federal prison – it could have been much longer.

Therefore, when Jimmie Crabb got the news in October of 1939 that his perjury conviction had been overturned and he wouldn’t have to go to prison, his own father was then at Leavenworth serving his sentences for bank fraud, and Jimmie had recently returned from a visit of the prison.

Though Jimmie’s legal troubles were over, Betty’s death and its consequences continued to haunt him. He had tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps, but with his court record the Army would not take him. And so, instead of being groomed to follow his father in banking, Jimmie spent much of 1939 working road construction jobs in West Virginia.

He came back to Central Illinois 50 pounds lighter. His weight loss was partly due to the manual labor, but there was very likely another reason: depression.

The lamentable conclusion of this story, appropriately enough, came on Halloween in 1940. Following is the report published in the 6 Nov. 1940 Astoria Argus-Searchlight:

“James Crabb Found Dying In Hotel Room

“Death Of Member Of Banking Family Attributed To Pneumonia

“Detroit, Oct. 31 — James W. Crabb, 24, member of a Delavan, Ill., banking family who twice faced charges resulting from the fatal shooting of his 19-year old wife, died at 5:30 a.m. today in a receiving hospital.

“Physicians attributed Crabb’s death to pneumonia complications. His mother, Mrs. Elizabeth M. Crabb, was at his bedside.

“Sergeant Hyman Ulnick of the police homicide squad said Crabb was found unconscious yesterday in a room at the Paul Revere hotel where he had registered under the name of ‘Wall.’

“Police said Crabb was arrested in March, 1938, and charged with responsibility for the death of his bride of five weeks, who was found fatally shot shortly after she and her husband returned from a party in their honor.

“Crabb maintained the shooting was accidental, police said. He was charged with manslaughter but the jury disagreed. Later he was convicted on a perjury charge resulting from the first trial, but the Illinois state supreme court reversed the verdict and remanded to the Tazewell county circuit court.

“Ulnick said identification was established through a social security card which bore the name of James W. Crabb, Bloomington, Ill. Crabb has been residing recently in Bloomington, but recently informed friends there he was going to accept employment.

“The death of James Crabb was a tragic climax to a chain of adverse events that beset the Crabb family, holder of a high position in business and society for three generations.

“When the first misfortune — the fatal shooting of Betty Collison Crabb — visited the family, Willis Crabb was a respected banker, landowner, and civic leader of a flourishing Illinois city. He poured much of his fortune into the defense of his only son, charged with manslaughter.”

There are two significant fact errors in this news report. First, Ulnick was mistaken about Jimmie signing into the hotel under the name “Wall” – he registered under his own name, but Ulnick and the hotel clerk misread his signature.

Second, and most importantly: Jimmie did not die of pneumonia. His death certificate lists pneumonia as only a secondary or contributing factor. The actual cause of death was an overdose of sleeping pills – evidently an intentional overdose. A coroner’s jury ruled his death a suicide.

Jimmie was in just the early stages of pneumonia. The day he died, he went to a pharmacy and purchased cold medication, and a bottle of sleeping pills. Then he checked into the hotel, went up to his room, got a glass of water, and emptied the bottle of sleeping pills.

The former scion of a banking family had only 8 cents in his pocket when he died.

Jimmie’s mother Elizabeth had him entombed in Park Hill Mausoleum in Bloomington. His father Willis elected not to seek permission to attend his son’s funeral, saying he preferred to remember his son the way he was before the nightmare began in 1938.

Willis discharged his sentence in 1943 and returned to Illinois a broken man. He died 30 July 1947 in Jacksonville, Illinois, and was buried in Lot 26 of Prairie Rest Cemetery in Delavan – the same lot where Betty Crabb had been laid to rest.

Her parents later had her reinterred in Rantoul, no doubt unhappy that she was in the same cemetery lot as the father of the man whom they believed murdered her.

On Betty’s gravestone, her married name of “Crabb” is nowhere to be found.