Here’s a chance to read one of our old Local History Room columns, first published in June 2012 before the launch of this blog . . .

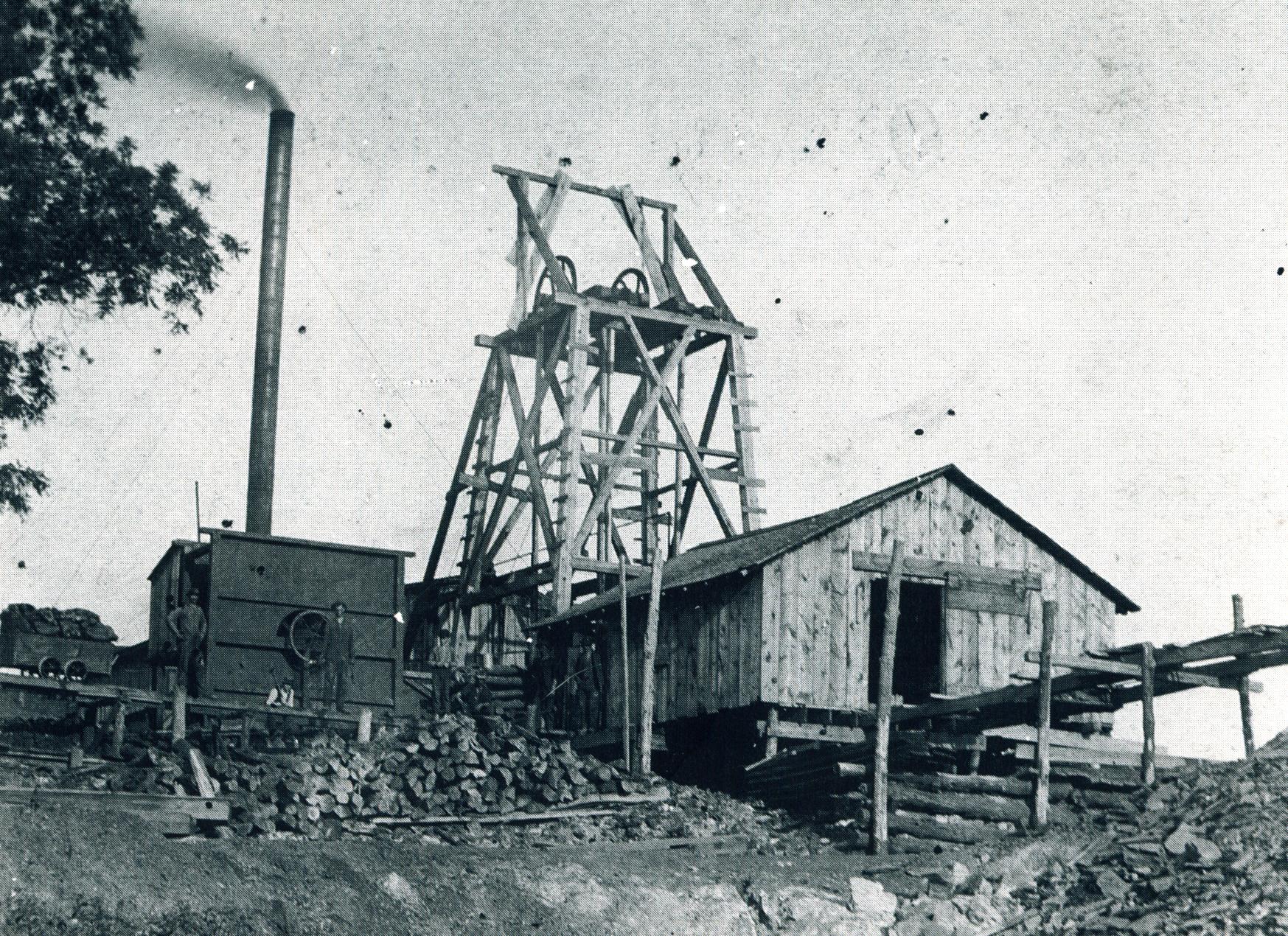

In his 1905 “History of Tazewell County,” Ben C. Allensworth called it “the most serious riot ever known in Tazewell County.” It was the Little Mine Riot of June 6, 1894, which took place at the Hilliard Mine near Creve Coeur (then known as Wesley City). This event didn’t get its name because the riot or the mine were little, but because the Hilliard Mine was leased by the brothers Peter and Edward Little, coal-mine operators of Peoria County.

The Pekin Public Library’s local history room collection has only Allensworth’s account of this incident. Local historian Fred W. Soady, however, went into greater depth in his master’s thesis, “Little Mine Riot of 1894: A Study of a Central Illinois Labor Dispute.”

“Labor” and “management” sometimes have differences that lead to a falling out, and workers go on strike. Such disputes usually don’t involve exchanges of gunfire and people shot to death, as happened in the Little Mine Riot, but relations between the Littles and their miners had deteriorated drastically.

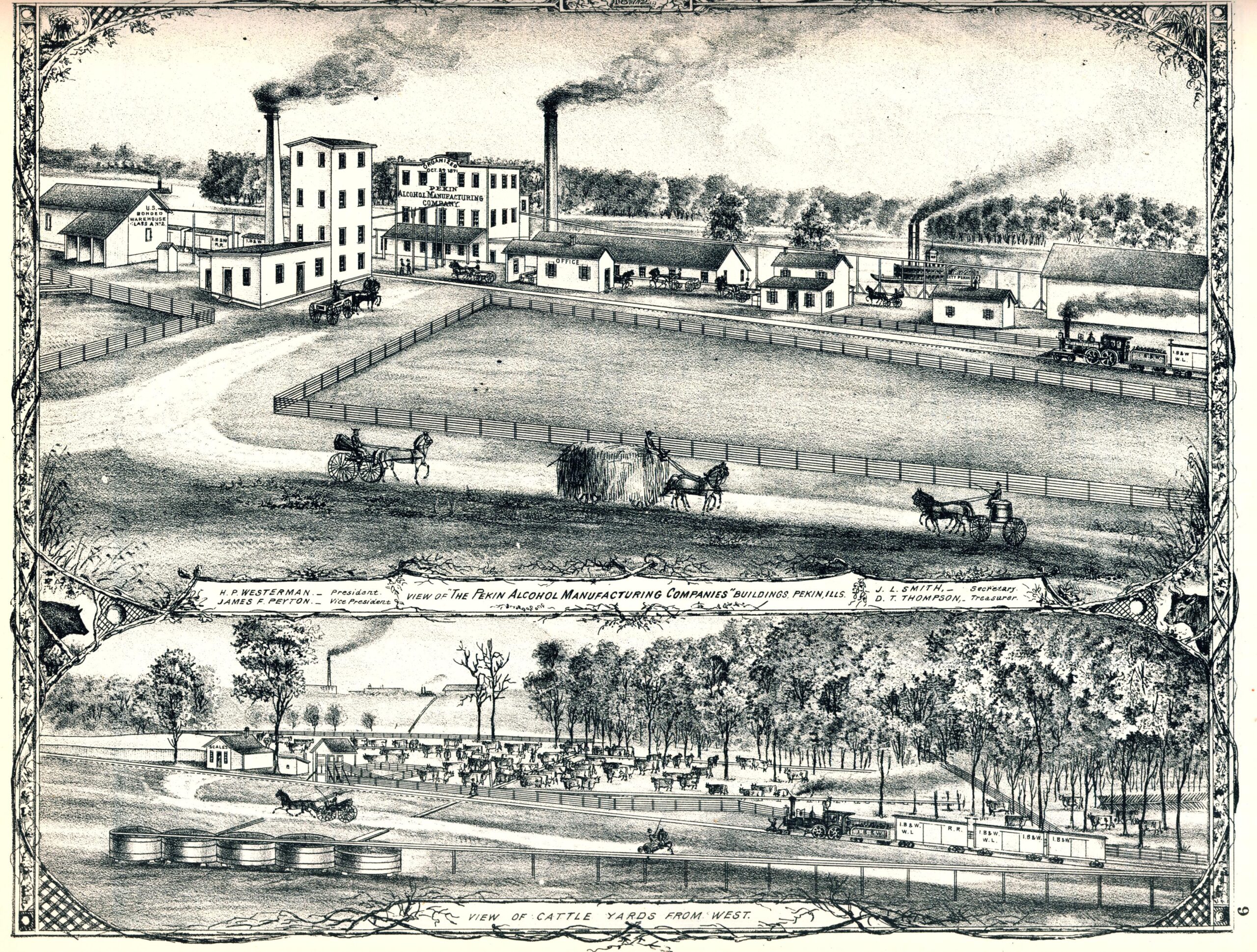

The miners’ immediate and primary grievance, according to Allensworth, was that the Littles had installed new machinery that meant fewer men were needed to work the mine. In addition, “The miners in Peoria County had been on a strike for some time, and the fact that coal was being taken daily from the Hilliard Mine seemed to be a source of aggravation,” Allensworth wrote. Local historian Dale Kuntz, however, has observed that ethnic and racial tensions also contributed to their unhappiness – the Littles employed Italian Catholic immigrants and African-Americans.

As Allensworth told the story, “The result was that threats by the strikers to close their mine came to the ears of the Littles, and they prepared for trouble by storing guns and ammunition in the tower which overlooked the valley below. On June 15th (sic), Sheriff J.C. Friederich received the following telegram from Ed. Little: ‘The miners are coming tomorrow, five hundred strong, and armed. Be on hand early.’ Sheriff Friederich and Deputy Frings swore in about thirty deputies. They could secure no weapons worthy of mention, and, consequently, went up unarmed. In the meantime about three hundred miners assembled on the opposite side of the river, and nearly all armed with guns, pistols and other deadly weapons. They crossed the river in boats, and under the leadership of John L. Geher, an ex-member of the Legislature, marched to the mine. The sight of the mine in operation seemed to enrage them beyond control, and they started on a run for the works. They were met by the Sheriff, who asked them to abstain from violence, and commanded them to disperse. They brushed the sheriff and his deputies aside, and began firing in the tower. The assault was replied to by the Littles, striking a miner by the name of Edward Flower, who fell dead.”

Unsurprisingly, some details of this incident are unclear and disputed. The miners claimed the Littles shot first, and Ed Little is reported to have admitted as much, and to have said Geher had done all he could to avoid violence. The miners also protested that they were provoked by the proud and domineering attitude of one of the Little brothers.

Allensworth’s account continues, “In the tower were the Little brothers, William Dickson, colored, Charles Rockey and John Fash. Seeing that resistance was useless, they ran out a flag of truce. Both the Littles and James Little, a son, were wounded. Dickson attempted to escape but was followed and shot several times, was taken to a Peoria hospital and died there. The miners completed the work of destruction by pouring coal oil down the shaft and setting fire to it. Some eleven men were working in the mine at the time, but all succeeded in making their escape.”

When news of the riot reached the ears of Gov. John P. Altgeld, two companies of the state militia were sent to Tazewell County, which was virtually placed under martial law for about a week. Residents of Pekin also organized a company of guards to defend the city, because the striking miners had threatened to come to Pekin and break their friends out of the county jail.

In the end, cooler heads prevailed and the rule of law was restored. In September 1894, Geher, Daniel Caddell, John Heathcote, and a man named Jones, were sentenced to be imprisoned for five years in the state penitentiary in Joliet, but Gov. Altgeld pardoned them after they had served about a year of their sentences.

The Littles also filed a claim for damages to their business and were awarded $7,710.60, and to ensure that Tazewell County would not again be caught unprepared for major civil disturbances, the county purchased 100 Remington rifles.