This week we conclude our series on Pekin’s 1924 Centennial Celebration with a “post script” on a remarkable feature of the celebration that would be unacceptable today: the “Indian Village” at Mineral Springs Park that was presided over by a man calling himself “Chief White Eagle.”

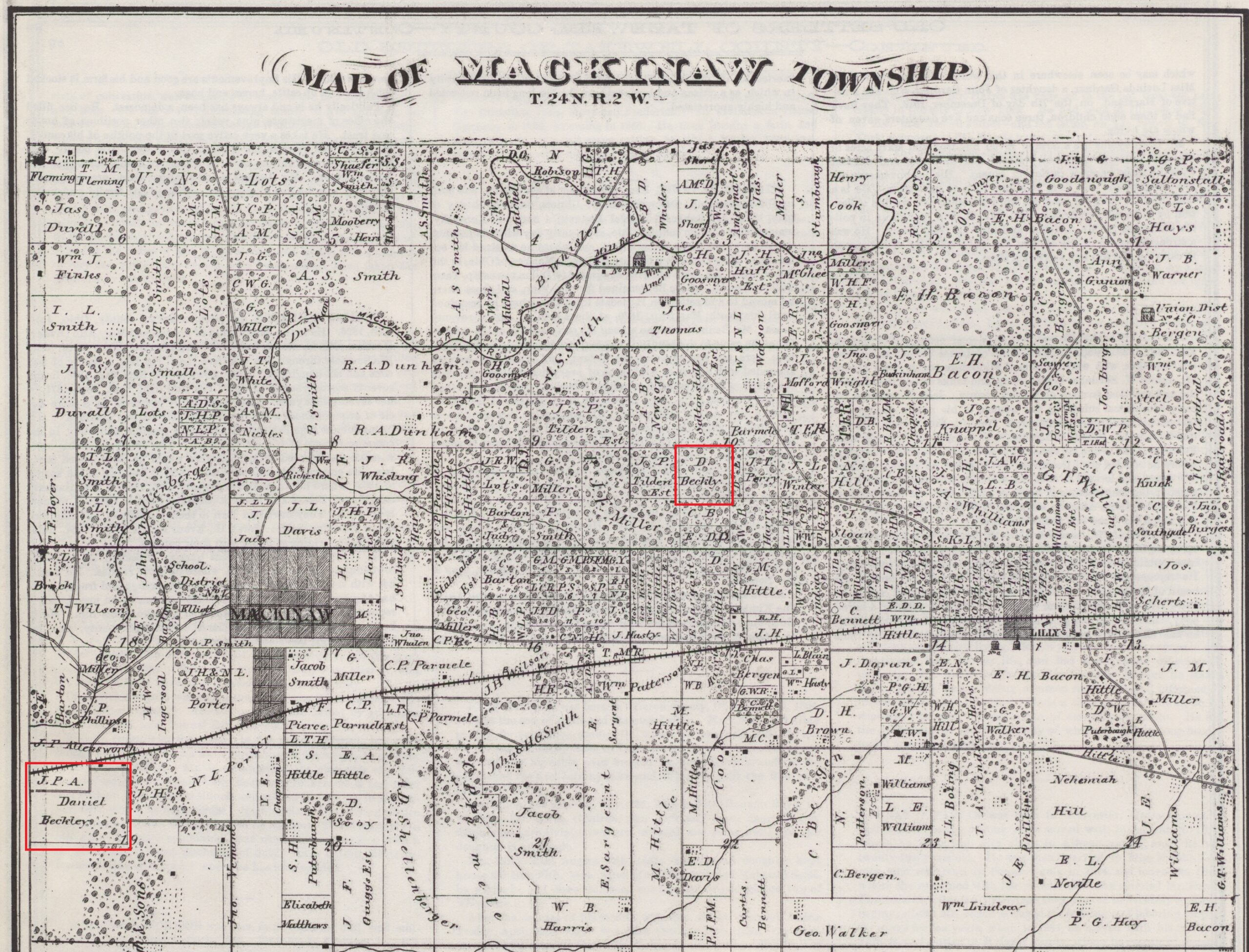

In the months leading up to the celebration, the Centennial’s planning committee wished to acknowledge the Native peoples who lived at the site of Pekin at the time of Jonathan Tharp’s arrival in 1824. During the 1820s and early 1830s, a village made up of several hundred Native Americans – chiefly Pottawatomi and Kickapoo – was located along the shores of Pekin Lake in the general area where Lakeside and Sacred Heart cemeteries are today. These Native Americans were deported to reservations west of the Mississippi after the 1832 Black Hawk War, along with the rest of Illinois’ American Indian population (except for Pottawatomi peace chief Shabbona and his family, who were allowed a small reservation that later was illegally forfeited; the reservation was federally recognized this year).

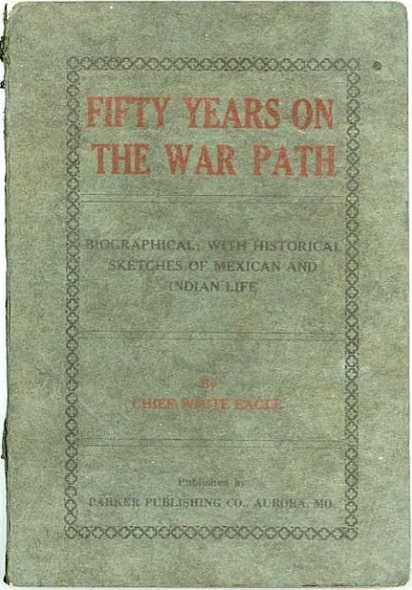

Hoping to offer the celebration’s attendees an authentic representation of traditional American Indian life, history, and culture, the committee invited a noted itinerant Baptist preacher and lecturer named John Freeman Craig (1865-1944) to come to Pekin during the Centennial Celebration and set up an “Indian Village” at Mineral Springs Park. Craig was better known as “Chief White Eagle,” giving out his Native American name as “Shaw-Aow-Shep-Scaw-Hunka” and claiming that his mother was full-blooded Winnebago (Ho-Chunk). In the early 20th century, Craig traveled around the country presenting programs and lectures on American Indian culture and customs.

A few days before the start of the Centennial Celebration, the Friday, 27 June 1924 edition of the Pekin Daily Times published a front page, above-the-fold story about “Chief White Eagle” and the planned “Indian Village” at the park. A transcription of that story is presented below – but readers should be forewarned that the article uses luridly sensational language (common in newspapers of that period) that presents almost all of the old racially-charged stereotypes of American Indians and of their ancient ways of life, stereotypes that were then deeply-ingrained in white American culture.

Real Live Indians, Headed By Chief White Eagle, Is Centennial Feature

Indians, as savage as any that ever scalped a white pioneer, as primitive as those that wandered the Illinois prairie a century ago, painted warriors with multi-colored feathers, docile squaws and soft-eyed Indian maids, will lead the spectacular historical parade of the Centennial one week from today.

The savage tribes will be led by Chief White Eagle, native Indian, evangelist and lecturer. He is a Shoshone Indian, a direct descendant of the cliff dwellers. Perhaps no living man is more versed in the lore of the redskins and at the same time more learned in the ways of the white man. He is an ordained Baptist minister, a graduate of the Lawrence college at Appleton, Wisconsin, and a veteran of the Spanish-American war. As a lecturer he is famed throughout the middlewest. Sioux Indians, Winnebagoes, Chippewas, San Juan Indians and descendants of the cliff dwellers will march in advance of the floats in the historical parade. To this vanguard of the Century parade the pavements of Pekin will again become the narrow paths of the prairie and their march will be accentuated with the weird rhythm of the tom-tom while the war dance, the sun dance, and snake dance and the give dance of the American Indian is revived.

At the park Chief White Eagle has arranged for tableau reproductions of such historic scenes as the “Treaty of William Penn,” the “Traitor About To Be Burned at the Stake,” who is rescued by the Chief’s Daughter. This will be a part of the Indian Village which will be on display for Centennial celebrators during the three days of festivity.

At five o’clock each evening Chief White Eagle will deliver instructive and entertaining lectures on Indian life at the “trading post” of the village.

July 4th will be the Chief’s 59th birthday and he points to the record of having delivered a lecture somewhere in the west on every Fourth of July for the past 35 years.

The official Pekin Centennial Program, published on the front page of the Thursday, 26 June 1924, edition of the Pekin Daily Times, says the Indian Village consisted of “25 braves, 10 squaws, 7 papooses, and a medicine man.” The program says at 5:30 p.m. on the first day of the celebration, there was to be a “Pantomime and Play at the Indian Village. Wm. Penn and Chief White Eagle will sign the Peace Treaty.” On the celebration’s second day, also at 5:30 p.m., would be an “Indian Play – The Story of Pocahontas, at the Indian Village.” Finally, on the third day at 5:30 p.m. would be an “Indian Pantomime and Play at the Indian Village. War Dances, Feed Dance, Corn Dance.”

A few days after the close of Pekin’s Centennial Celebration, the Pekin Daily Times on Monday, 7 July 1924, published a front page Konisek photograph titled “Chief White Eagle 59th Birthday, Pekin Centennial 1924.” The photo’s caption reads, “This is Dr. J. F. Craig, better known as ‘White Eagle,’ in the war paint and regalia of a red skin. White Eagle established an Indian village at the park during the Centennial celebration where customs and traditions of the Indians were authentically portrayed. Chief White Eagle lectured to large crowds at the village every evening during the festival and he led the historical pageant last Friday afternoon.”

The Pekin Centennial Celebration’s “Indian Village” was much like the traveling “Wild West” and Indian shows that were popular across the United States in those days. The players in those shows could include both authentic Native Americans and whites portraying Native Americans, but often had no authentic American Indians at all. For example, just one year after Pekin’s Centennial, Lillian “Red Wing” St. Cyr (1884-1974), a member of the Winnebago tribe, took part in the Centennial Celebration of Akron, Ohio, on 20 July 1925 (See Linda M. Waggoner’s book, “Starring Red Wing! The Incredible Career of Lillian M. St. Cyr, the First Native American Film Star” (2019), page 269).

We can’t be sure how many real Native Americans were members of Pekin’s Centennial “Indian Village.” The village’s members included not only “Chief White Eagle” and his companions who came to Pekin for the celebration, but also Pekin residents who donned make up and Native American dress to take part in the plays and pantomimes.

However, it is probable that, despite the intentions of the Centennial’s planners to include authentic American Indians in the celebration, the only people who took part in Pekin’s village were whites play-acting as Indians. Although John Freeman Craig, a.k.a. “White Eagle,” claimed in his 99-page book, “Fifty Years on the Warpath,” that his mother was a full-blooded Winnebago, and the Pekin Daily Times reported that Craig was a Shoshone, in fact Craig had not the smallest drop of Native American blood. He was what is colloquially known as a “Pretendian.” Craig’s book contains several clues suggesting that he wasn’t the real deal. For instance, before his career as an itinerant Baptist preacher and “Indian lecturer,” Craig said he was a medicine show huckster peddling quack cures. “I kept the druggist busy putting up my dope for two pitches a day,” he wrote. Significantly, when Red Wing St. Cyr appeared at the Akron Centennial in 1925, a “Chief White Eagle” was there too – and that “White Eagle” wasn’t John Freeman Craig (Waggoner, ibid.).

The only thing Craig shared with the Ho-Chunk were his Wisconsin roots – he was born in Lima, Sheboygan County, Wisconsin, reportedly on the Fourth of July. His father was a man of Scottish, English, and Welsh descent named Ezekial Lametosh Craig (1830-1921), who had been born in Maine, a son of Freeman Craig and Sylvia Delano, while his mother Lovina Hammond (1832-1918) was the daughter of Orin Hammond (1808-1898) and Rachel (Stone/Stevens) Hammond, both of whom were born in New York State. Being neither Ho-Chunk nor Shoshone, the ancestry of Orin and Rachel shows entirely white colonial New England origins. (See also the note on page 395 of Linda M. Waggoner’s book, “Starring Red Wing!” (2019).)

Because Craig’s claimed identity as “Chief White Eagle” is known to be false, other details of his life are also doubtful. Was he really an ordained Baptist minister? Was he really born on the Fourth of July? How authentic were the Native American customs and lore with which he regaled Pekin’s Centennial-goers? In any case, it is known that Craig made his home in Kansas City, Missouri, first settling there in 1917, and it was there he died on 16 July 1944 in his home at 1331 Forest St. He is buried in Green Lawn Cemetery, Kansas City.

It should be noted that although Craig had adopted the false persona of “Chief White Eagle,” he should not be confused with the white actor Basil F. Heath (1917-2011), born in London, England, of English and Brazilian/Portuguese-Amazonian Native American parents, who performed under the name “Chief White Eagle” from the 1930s to the 1960s and closely identified with Native American culture. Nor should he be confused with White Eagle (1825-1914), prominent Native American leader who served as hereditary chief of the Ponca from 1870 to 1904.