This week we revisit once more the life of “Black Nance” Legins-Costley of Pekin, who has the distinction of being the first African-American slave freed by Abraham Lincoln.

As noted in this column on three previous occasions (Feb. 11, 2012, May 2, 2015, and June 20, 2015), Nance was brought to Pekin as a slave by Pekin co-founder Nathan Cromwell, but persistently brought legal challenges to her servitude. Through Bailey v. Cromwell, a case that Lincoln successfully argued before the Illinois Supreme Court on July 23, 1841, Nance finally obtained freedom for herself and her three eldest children, Amanda, Eliza Jane and Bill. As we learned in June, Bill later served in the Union Army during the Civil War and was present for the founding of the Buffalo Soldiers and the first “Juneteenth.”

For all that we now know of “Black Nance,” there is much that is, and perhaps always will be, shrouded in mystery. Among those mysteries are the exact time and place of her birth, the exact time and place of her death, and her final resting place.

The research of Carl Adams, formerly of North Pekin, has established that Nance’s parents were African-American slaves named Randol and Anachy Legins, who were born in the 1770s in Maryland. (See Adams’s book, “Nance: Trials of the First Slave Freed by Abraham Lincoln”) Nance had a brother named Ruben “Ruby” Legins, born about 1808, and a sister named Dice Legins, born about 1815. Both the 1850 and the 1860 U.S. Census returns for Pekin say Nance was born in Maryland, and her given age in those census records indicates that she was born about 1813. Illinois Supreme Court records, however, say Nance was born in the building that would be used as the Illinois Territorial Capitol in Kaskaskia, Illinois. It’s impossible to get any closer to when and where she was born than that.

As for the date of Nance’s marriage, Tazewell County records show that she and Benjamin Costley were married before Justice of the Peace M. Tackaberry on Oct. 15, 1840. U.S. Census records indicate that her eldest child Amanda was born about 1836 in Illinois, though Amanda’s burial records indicate she was born July 3, 1834. Nance had been brought to the future site of Pekin by Nathan Cromwell around 1828. Adams notes that there is no indication that her husband had ever been a slave.

But when and where did Nance die, and where was she buried? Researchers have put forward two conjectures about her death and burial. According to Adams, the first conjecture was made by the late local historian Fred Soady, whose opinion is recorded in the 1974 Pekin Sesquicentennial volume as follows:

“[Nance] lived in Pekin until her death about 1873 at approximately 60 years of age … There is no record of her place of burial, although educated speculation would indicate the present site of the Quaker Oats Company.”

That would be the former city cemetery that was located at the foot of Koch Street, on the west side of Second Street. That cemetery was later closed and the burials were moved to Lakeside Cemetery along Route 29. So, if she was buried in the old cemetery, perhaps her mortal remains are now in Lakeside Cemetery, lacking a grave marker.

There are a few facts that conflict with Soady’s conjecture, however. For one thing, the 1880 U.S. Census lists “Nancy Costly,” age 85, as a resident of Pekin, along with husband Ben Costly, 87, and children Mary Costly, 50, at home, Willis Costly, 44, laborer, and Leander Costly, 35, laborer. If Nance died about 1873, why is she listed in the 1880 Census?

The answer to that question is that it seems this census record is fictitious. Adams and his collaborator Bill Maddox of Pekin had previously found a death record for Nance’s husband Ben in 1877 in Peoria, where it is known many of Nance and Ben’s children moved during the 1870s. If Ben was already dead in Peoria by 1877, he obviously couldn’t be alive and well in Pekin in 1880. It’s also significant that the ages of this 1880 census record contradict the ages listed for this family in earlier census records, which are quite consistent. Most likely this census record is a fabrication, perhaps intended to help boost Pekin’s population figures – but Nance’s family had left Pekin by 1880.

Is Soady’s conjecture that Nance died in Pekin around 1873 and was buried in the old city cemetery correct after all? Perhaps, perhaps not. Maddox has noted that if she did die in Pekin, she could have been buried on her own property, which was located at the southwest corner of Amanda and Somerset. Or perhaps she moved to Peoria with the rest of her family in the 1870s, and died there like her husband Ben. Maybe Nance and Ben are buried in Peoria.

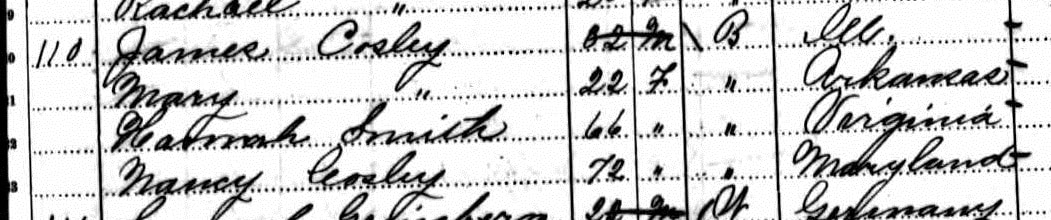

There is, however, another possibility that came to light earlier this year when this writer was researching the column of May 2, 2015. The Minnesota State Census returns for Minneapolis, dated May 29, 1885, list “Nancy Cosley,” 72, black, born in Maryland, with James Cosley, 32, black, born in Illinois, Mary Cosley, 22, black, born in Arkansas, and Hannah Smith, 66, black, born in Virginia. “Mary Cosley” of that entry could be James’ wife, and perhaps “Hannah Smith” is Mary’s mother, living in the same house with James and Nancy. The old Pekin city directories show that “Cosley” is one of the known variant spellings of Nance and Ben’s surname “Costley.” Nance had a son named James Willis Costley, who in fact would have been 32 in 1885, just as Nance, who was born in Maryland, would have been 72 that year.

record obtained through searching Ancestry.com databases shows a “Nancy Cosley” who was none other than Nance Legins-Costley of

Pekin. IMAGE PROVIDED

Could Nance not only have left Pekin but moved out of state to Minneapolis, Minnesota, living there with her son James Willis? Further research is necessary before this conjecture could be either confirmed or disproven, but the 1885 entry in the Minnesota State Census does “fit” with the other available known facts of Nance and her family.

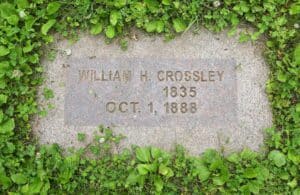

Significantly, Nancy’s eldest son Bill is known to have left Peoria for Iowa before moving to Minneapolis in the 1880s. Adams recently located Bill’s grave in Quarry Hill Park, in the Rochester State Hospital Cemetery, Rochester, Minnesota. Did James perhaps bring his mother to Minneapolis to join Bill there, or did Bill go to Minneapolis to join his brother and mother there? We can’t say for sure yet, but this state census record does raise the possibility that “Black Nance” did not die in Pekin about 1873, but perhaps died and was laid to rest in or near Minneapolis at some point after May 29, 1885.

Here are links to previous Local History Room columns on “Black Nance” and her family:

The first slave freed by Lincoln was from Pekin

Trials of the first slave freed by Lincoln