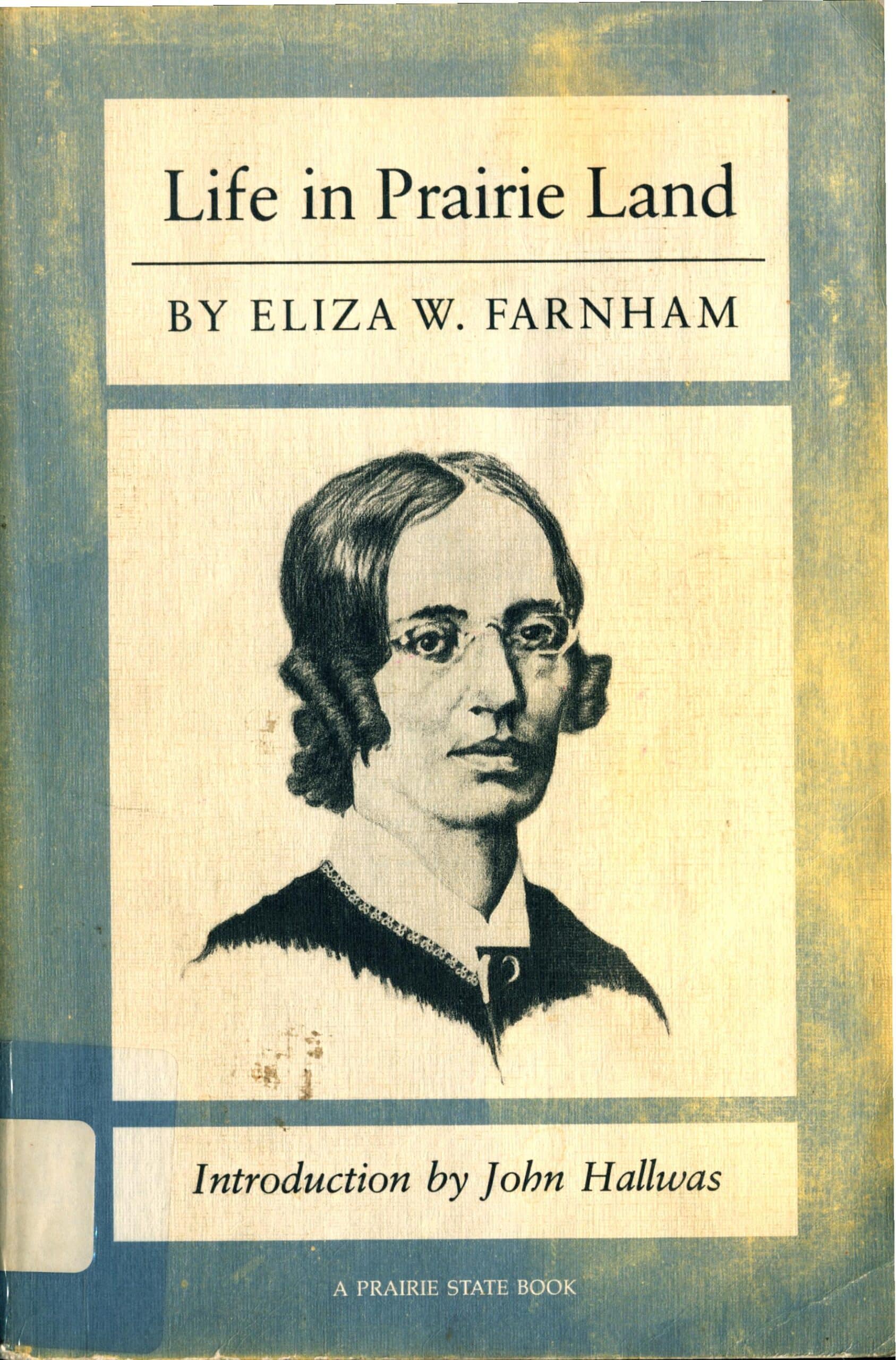

This column usually features resources from the Pekin Public Library’s Local History Room collection. These are items that remain in the library and may not be checked out. But this week we’ll turn our attention to a book in the library’s regular collection – a biographical narrative titled “Life in Prairie Land,” published in 1846 by an early feminist and abolitionist writer from New York State named Eliza W. Farnham.

The book describes Farnham’s experiences living in Illinois during the 1830s, a period when most of the state was a part of America’s wild frontier. Her book’s relevance to the history of Tazewell County and Pekin may be discerned from the following passage on page 24, in which Farnham tells the story of her arrival in central Illinois in 1836:

“We worried on through the flood of water that was pouring down the bed of the Illinois and submerging its banks, till the night of the fifth day brought us to the landing place of our friends in the town of Pokerton. It was at that time the county seat of one of the largest and wealthiest counties in the state. Its name is faintly descriptive of its inhabitants in a double sense: one of their favorite recreations being a game at cards, which is indicated by the first two syllables of this name. . . .”

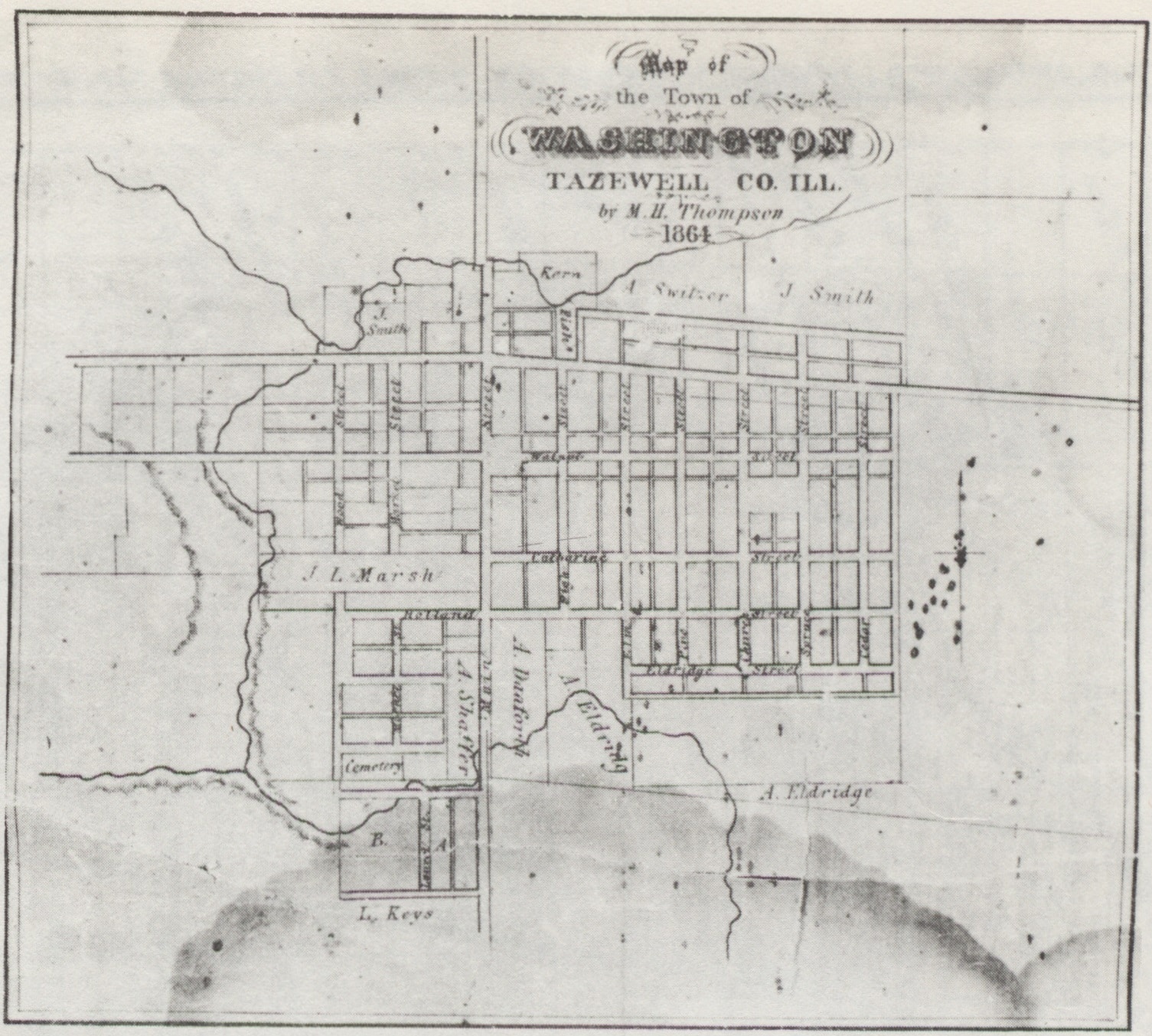

The county to which Farnham referred is none other than Tazewell County, and “Pokerton” is the disdainful monicker that Farnham invented for Pekin. It’s clear from the way Farnham describes Pekin and its residents that she was greatly unimpressed by Pekin, which was then hardly more than an undeveloped frontier village.

Born Eliza Wood Burhans (but later called Eliza Woodson) on Nov. 17, 1815, at Rensselaerville, N.Y., she was the fourth of five children of Cornelius and Mary (Wood) Burhans. Farnham, still unmarried when she came to Tazewell County, had left New York to live with her sister Mary for a while. Mary and her husband, John M. Roberts, an abolitionist involved in the Underground Railroad, settled near Groveland in 1831, on a homestead that they named Prairie Lodge. Another likely reason Eliza moved to Groveland was to be near a young man she’d met back East, Thomas Jefferson Farnham, a Vermont lawyer who had purchased land near Groveland in the summer of 1835. Eliza and Thomas married on July 12, 1836, settling in Tremont, which became the county seat that very year. (Remarkably, she never mentions Tremont by name in her book, not even using an alias of her own invention.)

The Farnhams lived in Tazewell County until the spring of 1839. While here, Eliza experienced the double sorrow of the death of her sister Mary in July 1838, followed two weeks later by the death of her own firstborn child during an epidemic. In her book, Farnham tells of her meditations on her bereavement that in time led her to move from her youthful atheist views to “a religious state of mind.”

The Farnhams brief stay in Tazewell County ended when Thomas organized a trip to Oregon, exploring the possibility of leading a group of settlers to the Pacific Northwest. Eliza stayed behind in Groveland and Peoria while her husband led the expedition. Upon his return in August 1840, the couple moved back to New York. So ended her experiences of “Life in Prairie Land.”

Farnham would go on to write several articles and books, and in particular was an advocate of feminism (she held that women were morally and biologically superior to men). She also became matron of the women’s half of Sing Sing Prison in Mount Pleasant, N.Y., where she implemented a series of reforms that were oriented toward rehabilitation of the inmates. Due to strong opposition to her reforms, she resigned her position in 1848.

That same year, her husband Thomas died in San Francisco, Calif., which necessitated her own move to California to settle his estate. Those years in California were unhappy ones – she suffered the loss of two of her children, and her second marriage in 1852 to William Fitzpatrick ended with her divorcing him in 1856. Farnham returned to New York for a few years, promoting her feminist views, then moved back to California for a while, then back to the East to advocate for the abolition of slavery. In 1863, as a volunteer nurse at Gettysburg, she contracted tuberculosis. She died Dec. 15, 1864, in New York City and was buried in the Quaker Cemetery at Milton-on-Hudson, N.Y.