During this year of the U.S. Semiquincentennial, it is an opportune time to recall the long and rocky — and often bloody — path that brought America to the point where the promise of liberty conceived at its founding in 1776 could finally be fulfilled. This week we will recall the historic efforts to abolish slavery, with a focus on the Tazewell County Anti-Slavery Society and its members who ran the Underground Railroad in our county.

Though the Declaration of Independence famously declares, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” nevertheless it would take many decades and a bloody civil war before slavery would be abolished, and even longer before all men would actually be treated equally in law and in society.

Leading the fight against chattel slavery were the abolitionists, who strove to change hearts, minds, and laws in order to rid the country of an institution that reduced the vast majority of blacks in America to the status of property that could be bought or sold, whipped, beaten, or raped without any regard for their humanity.

Today we look back upon the abolitionists with honor and gratitude for their courage and their integrity. But at the time, abolitionists were regarded with disgust by most Americans, viewed as extremists and religious fanatics who wanted to overturn the natural order. Admittedly some, like John Brown, were committed to violent means to advance their cause (Brown and his family even went as far as committing murder) — but Brown was indeed an extreme case and his crimes were deplored even by abolitionists. Most abolitionists pursued peaceful means, seeking to persuade and striving to reform U.S. and state laws, and going out of their way to assist fugitive freedom-seekers at a time when to do so meant flouting unjust laws and risking their own lives and livelihoods.

The abolitionist networks by which they helped escaping enslaved persons is known as the Underground Railroad — a “freedom train” that ran on “liberty lines.” Historical sources that tell of the abolitionist movement in Illinois include the abolitionist newspapers Western Citizen and Genius of Liberty. Another valuable secondary source is Delores T. Saunders’ “Illinois Liberty Lines,” published in Farmington, Illinois, in 1982. Saunders’ work was one of the chief sources that was used by Susan Rynerson in her series on Tazewell County’s Underground Railroad conducts that was printed a few years ago in the Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society’s Monthly. Rynerson’s series is the chief source for the follow account of the Tazewell County Anti-Slavery Society and Underground Railroad.

One of the older standard works on our local history is the 1879 “History of Tazewell County” that was compiled and edited by Charles C. Chapman. In that book, Chapman devoted an entire chapter of his book – chapter IX – to the running of the Underground Railroad in Tazewell County, on which the “freight” were human beings seeking freedom. As Chapman explains, abolitionists in Illinois frequently encountered fierce and violent opposition from pro-slavery settlers. Those whose moral convictions spurred them to assist “runaway slaves” also risked punishment, since both federal and state law prescribed stiff penalties not only for anyone who helped a runaway slave gain his freedom but also for anyone who refused to help recapture “runaways.”

“Pro-slavery men complained bitterly of the violation of the law by their abolition neighbors, and persecuted them as much as they dared: and this was not a little. But the friends of the slaves were not to be deterred by persecution,” Chapman writes.

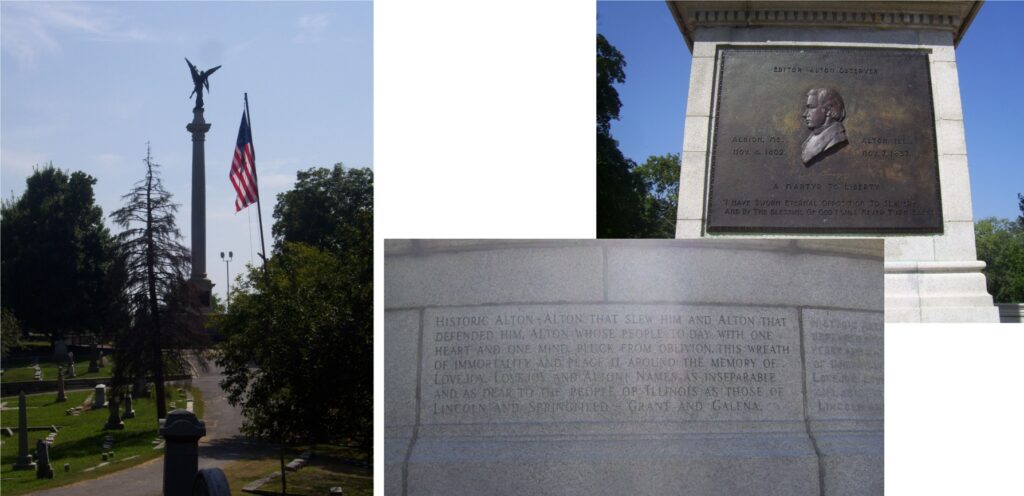

The story of the activities of the Tazewell County Anti-Slavery Society is part of the wider story of abolitionism in the U.S. and Illinois. Looming large in the story of the Illinois abolitionists are three brothers, the Rev. Elijah Parish Lovejoy (1802-1837), Joseph Cammett Lovejoy (1805-1871), and the Rev. Owen Lovejoy (1811-1864), who were sons of a Congregationalist minister from Albion, Maine. Elijah Lovejoy was a talent journalist and an ordained Presbyterian minister, and was motivated by his fervent religious faith to oppose slavery. He published an abolitionist newspaper in St. Louis, Missouri, the St. Louis Observer. Driven from St. Louis by pro-slavery mobs who destroyed his printing press, Lovejoy moved the Observer to Alton, Illinois, where he founded Illinois’ Anti-Slavery Society on 26 Oct. 1837 (though slavers invaded and disrupted the Society’s organizing convention). Soon a pro-slavery mob again destroyed his press. On 7 Nov. 1837 a new press was delivered. That night a mob attacked the guarded warehouse where the new press was stored. Lovejoy was gunned down.

His younger brother Owen was there that night. Later he would recall, “Beside the prostrate body of my murdered brother Elijah, while fresh blood was oozing from his perforated breast, on my knees while alone with the dead and with God, I vowed never to forsake the cause that was sprinkled with his blood.”

No funeral service was held for Elijah Lovejoy and the Alton Observer ignored his death. He was initially buried in an unmarked grave behind Alton Cemetery, later being reinterred north of his monument. His grave did not get a marker until 1860, and the majestic Lovejoy Monument now at Alton Cemetery was not erected until 1897.

Elijah’s brothers Joseph and Owen prepared his biography: “Memoir of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy, who was murdered in defense of the liberty of the press, at Alton, Illinois, Nov. 7, 1837,” published by the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York in 1838, with a forward written by former U.S. Pres. John Quincy Adams. The same year Lovejoy’s memoir was published, the Tazewell County Anti-Slavery Society was established.

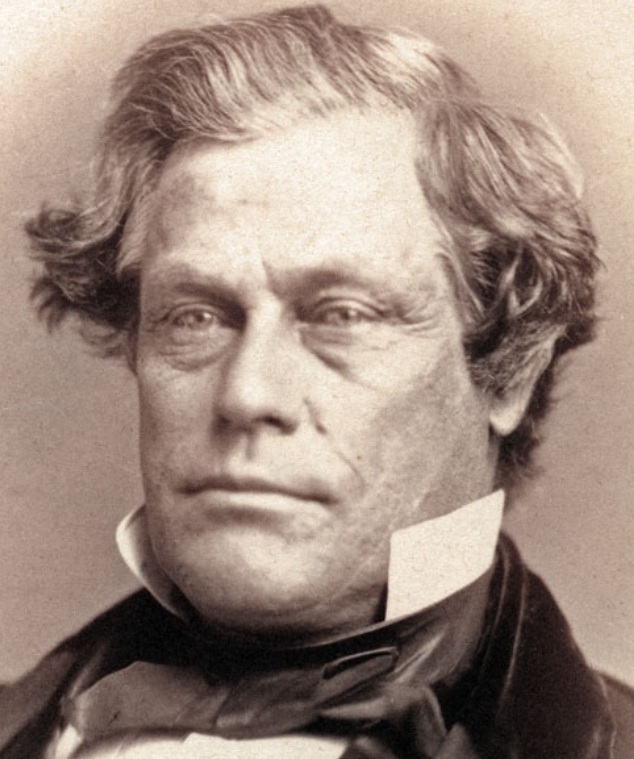

Owen Lovejoy served as pastor of the Congregationalist church in Princeton, Illinois, from 1838 to 1856 and was an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society. Many of the 115 Congregationalist churches (all anti-slavery) established during those years were organized by Rev. Owen Lovejoy. His wife’s 1,300-acre farm in Princeton was a station on the Underground Railroad – passage through Bureau County was called “riding the Lovejoy Line.” He was even tried for harboring runaway slaves in 1843 but was acquitted, because the jury was unwilling to imprison him along with his wife Eunice, their children, and his aged great-grandparents.

Drawn to take a personal role in politics, Rev. Lovejoy began his political career in 1854 when he was elected to the Illinois General Assembly. He was later one of the key organizers of the Republican Party in 1856. Leaving his position as minister, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, serving from 1857 until his death from cancer in 1864. As a Congressman, Lovejoy introduced the bill that banned slavery in the District of Columbia, and strove for the passage of the 13th Amendment that outlawed slavery throughout the U.S. Lovejoy was a close friend and advisor of President Lincoln. Upon Lovejoy’s death, Lincoln said, “To the day of his death, it would scarcely wrong any other to say, he was my most generous friend,” and, “I’ve lost the best friend I had in the House.”

His tireless efforts against slavery in Illinois brought him to Tazewell County more than once, and the leading abolitionists of Tazewell County were counted among his friends. Following is a list compiled by Susan Rynerson of the Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society, of the men in Tazewell County who are known to have been abolitionists. Many of these men were also Underground Railroad conductors.

Delavan:

- William Brown (1780-1852)

- Daniel Cheever (1769-1858)

- Daniel Cheever (1802-1877)

- Daniel Cheever (1827-1890)

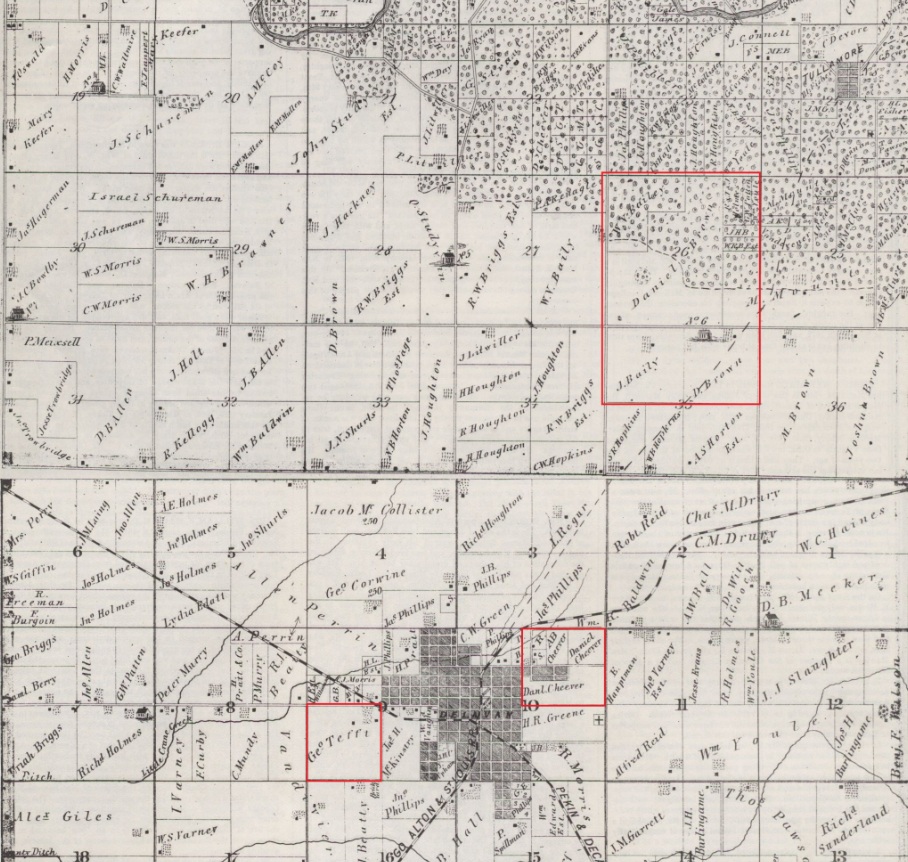

- George Tefft (1806-1875)

Dillon/Sand Prairie:

- Absalom Dillon (1787-1834)

- Samuel Woodrow (1798-1874)

- Hugh Woodrow (1794-1844)

- William Woodrow (1793-1866)

- Johnson Sommers (1792-1870)

- Roswell Grosvenor (1789-1866)

Tremont/Elm Grove:

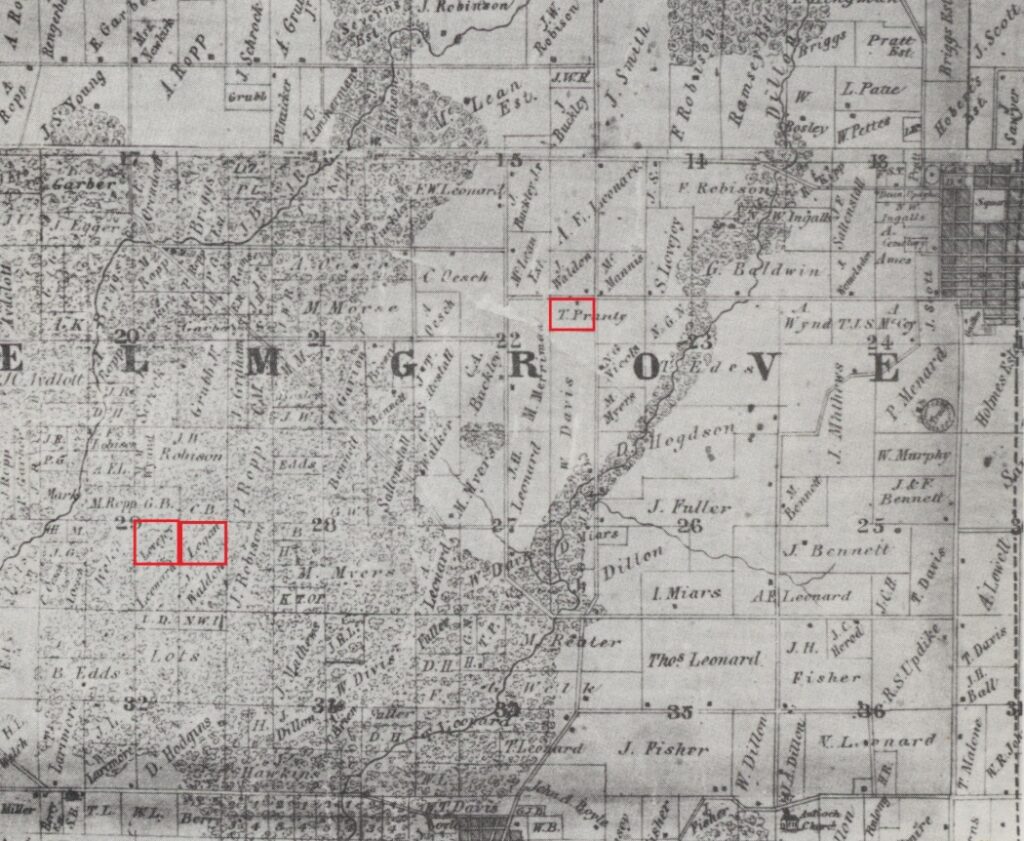

- Josiah Matthews (1803-1867)

- Levi R. Matthews (1830-1902)

- John A. Jones (1806-1888)

- Freeman Kingman (1799-1879)

- William Duncan Briggs (1819-1853)

- Peter Logan (c.1780-1866)

Groveland/Morton:

- Charles Rice Crandall (1818-1906)

- George F. Crandall (1820-?)

- Chauncey Crandall (1823-1847)

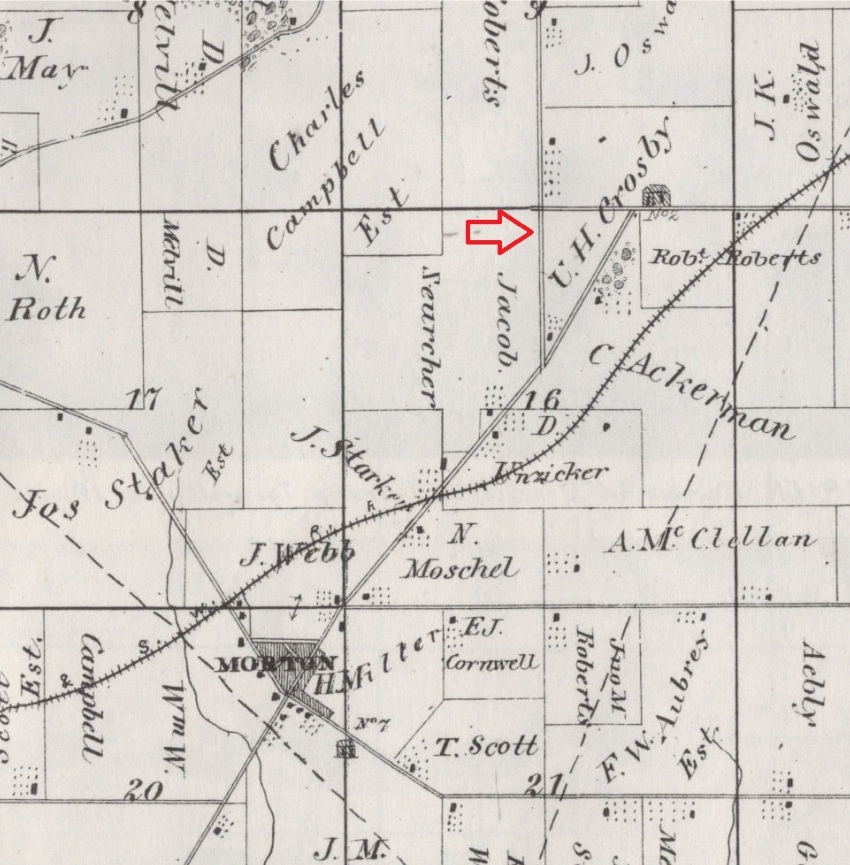

- Uriah H. Crosby (1811-1885)

- Horatio N. Crosby (1808-1889)

- Horatio N. Crosby (1840-1922)

- Anthony Field (1808-1878)

- Willard Gray (and Deacon Gray) (1806-1874)

- Benjamin O’Brien (1820-1901)

- Daniel Roberts (1782-1858)

- Ambrose Roberts (1809-1885)

- John Montgomery Roberts (1807-1886)

- Junius Roberts (1833-1915)

- Darius Roberts (1813-1886)

- Walter Roberts (1815-1874)

Washington:

- James Patterson Scott (1805-1866)

- John Randolph Scott (1812-1894)

- Romulus Barnes (1800-1846)

- J. George Kern (1799-1883)

- James J. Kern (1823-1899)

The Western Citizen, 26 July 1842, lists Rev. Romulus Barnes of Washington and Roswell Grosvenor of Pekin among the agents of the male Anti-Slavery Society. Rev. Barnes came to Illinois as a missionary in 1831 and lived in Washington from 1834 to 1842. Roswell Grosvenor, secretary of the Tazewell County Anti-Slavery Society, purchased property in Dillon and Sand Prairie Townships and had his home in Sand Prairie. The 1841 obituary of his first wife Harriet L. (Chipman) Grosvenor says: “The slaves of our country she considered emphatically the oppressed, and the poor; and she could find no encouragement given her to hope that she would ever reach Heaven, unless, in truth, she loved them as herself.”

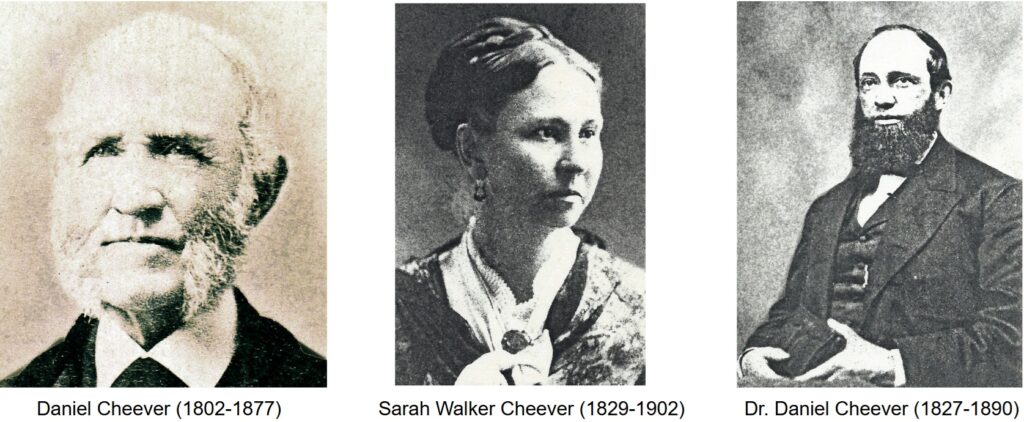

Grosvenor remarried at Pleasant Grove in 1841 (Rev. Hurlburt presiding) to Nancy Gordon Walker, widow of Robert Walker. Nancy’s eldest daughter Sarah Walker (1829-1902) married Dr. Daniel Cheever in 1852, a known Underground Railroad conductor whose station was on the east side of Delavan. Likewise, Roswell Grosvenor’s home was probably a U.G.R.R. station. Unsurprisingly, several other Tazewell County abolitionists were related by blood or marriage.

Although much of the dangerous work on the Underground Railroad was done by men, nevertheless the women of abolitionist families were just as committed to the cause and shared in the perils of their fathers, husbands, and sons. Thus, almost seven years after Elijah Lovejoy founded Illinois’ Anti-Slavery Society, and almost six years after the Tazewell Anti-Slavery Society was founded, a Female Anti-Slavery Society was organized on 23 May 1844 at the Main Street Presbyterian Church in Peoria. The meeting was chaired by Mrs. Codding, secretary was Mrs. Davis, and Mrs. Neeley, Mrs. Losey, and Mrs. Lucy Pettengill were appointed to the committee. Statewide officers elected at that meeting included: Mrs. Eunice Lovejoy and Mrs. Crittenden of Princeton, Mrs. M. B. Davis and Mrs. L. Pettengill of Peoria, Mrs. W. Willard and Mrs. John Roberts of Pleasant Grove, Tazewell County, Mrs. Willard and Mrs. A. B. Lewis of Washington, Mrs. Ranney and Mrs. Hurlburt of Morseville, Tazewell County [now Woodford].

The Underground Railroad line through Tazewell went through rural communities of Congregationalists, Quakers, and Amish Mennonites. The head of the line south of Tazewell County was a Quaker community, and the end of the line north of Tazewell County was also a Quaker community. The conductors and workers and their abolitionist allies were all motivated by their Christian faith – whether Quaker, Congregationalist, Mennonite, or Baptist – which taught them that humans made in God’s image can never be property to be bought or sold. Following is a list of Tazewell County’s known U.G.R.R. conductors, followed by further information about them, their stations, and their experiences.

- George Tefft (1806-1875) of rural Delavan.

- Daniel Cheever (1769-1858), son Daniel Cheever (1802-1877), and son Dr. Daniel Cheever (1827-1890) of Delavan (and Pekin).

- William Brown (1780-1852) of Dillon.

- Absalom Dillon (1787-1834) of Dillon.

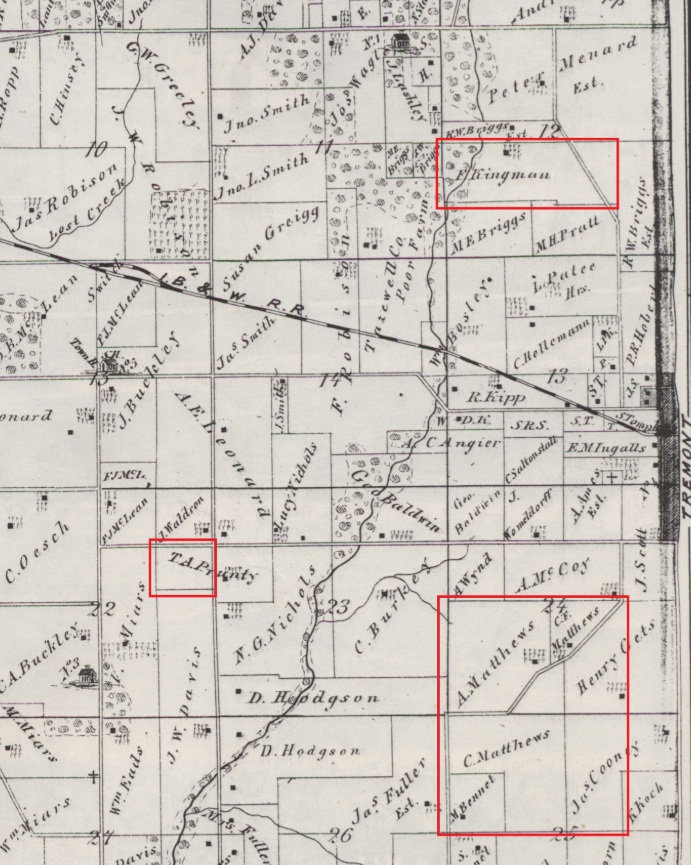

- Josiah Matthews of Elm Grove Township, near Tremont.

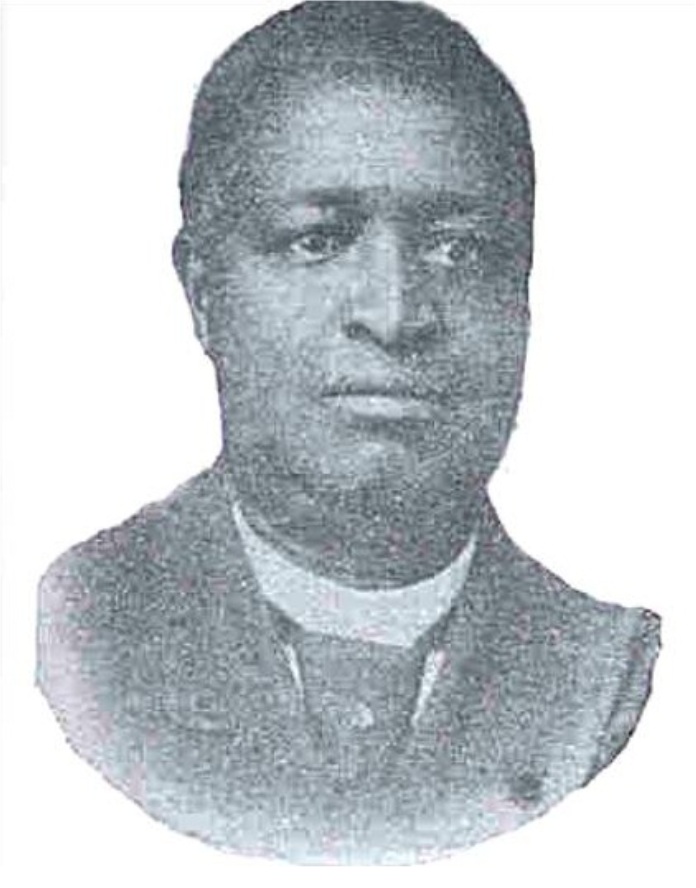

- Peter Logan of rural Tremont, a freedman who lived and farmed with his sister Charlotte and niece Nancy a few miles east of Tremont.

- John Albert Jones (1806-1888) of Tremont.

- Freeman Kingman (1799-1879) of rural Tremont.

- The Daniel Roberts (1782-1858) family: sons Darius, Walter, Ambrose, and John M. Roberts, and John’s son Junius. The Roberts Diary is a valuable primary source for the family’s U.G.R.R. activities, giving detailed itineraries and calendar dates for arrivals and shipments of “cargo.”

- Uriah H. Crosby (1811-1885) of Morton Township.

- J. Randolph Scott (1812-1894) and J. Patterson Scott (1805-1866) of Washington Township.

- J. George Kern and his son James J. Kern of rural Metamora.

Freedom-seekers in Tazewell County usually would be brought into the county along or near the old Springfield-to-Peoria Road, and would find refuge at the stations around Delavan. The Delavan Township U.G.R.R. conductors were:

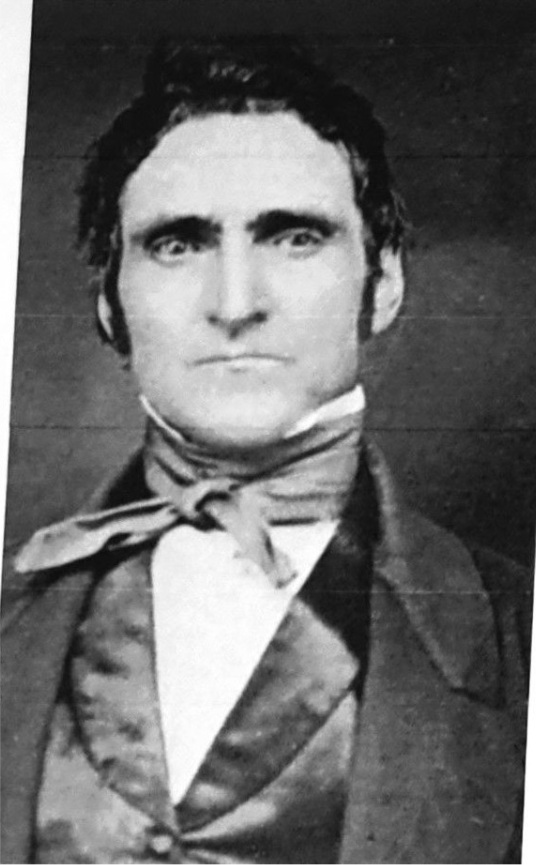

George Tefft (1806-1875) of rural Delavan. The Tefft home, one of the original homes of Delavan’s New England colony, was about 100 acres southwest of Delavan. Their home, which was framed in New England and shipped to Delavan by flatboat and ox cart, was apparently designed with a network of hiding places. It had six rooms on the first floor, three rooms on the second floor, three separate cellars with trap doors leading to two smaller rooms, four secret cubbyholes in the attic, a trap door in the pantry to the basement, and a bedroom closet with concealed access to the attic.

Daniel Cheever (1769-1858), his son Daniel Cheever (1802-1877), and his son Dr. Daniel Cheever (1827-1890), of Delavan (and Pekin). Dr. Cheever’s office was at the corner of Court and Capitol, but the Cheever farmstead was east of Delavan and was a U.G.R.R. station. Like the Tefft station, the Cheever station was an original Delavan colony house. Many of the New England colony settlers were Quakers and Congregationalists, spurred by their religious faith to oppose slavery. In a room above Dr. Cheever’s downtown Pekin office is where he and 10 other leading men of the county (including his fellow conductor John Albert Jones of Tremont) organized the Union League of American in June 1862. The 1949 Pekin Centenary claims Dr. Cheever engaged in U.G.R.R. activities at his office in Pekin, but it is extremely unlikely any freedom-seekers were ever sheltered there as it would be all but impossible to keep that a secret. Dr. Cheever, Jones, and George H. Harlow of the Pekin Union League were among the bodyguard for Lincoln at his Second Inaugural Address in April 1865.

William Brown (1780-1852) of rural Dillon. Noted in historical primary and secondary sources as “Abolitionist Brown.” He was elected to the Illinois General Assembly, serving at the same time as Abraham Lincoln. Browns’s farm was a station, located to the northeast of Delavan in Dillon Township.

From the Brown station, freedom-seekers would then be sent over the Mackinaw River to the Dillon settlement, named for the pioneer Dillon family, who were the second settler family of what would become Tazewell County. Arriving in 1823, Nathan Dillon (1793-1868) and his wife Mary (Hoskins) Dillon (1796-1869), and soon after, Nathan’s brothers, were the founders of a Quaker settlement in the area of Dillon in Tazewell County. Their son-in-law James J. Kern (1823-1899) and James’ father George in what was originally northern Tazewell County (but is now Woodford County) were both U.G.R.R. conductors. Nathan’s older brother was Absalom Dillon (1787-1834) of Dillon, whose homestead was a station. His wife Gulielma (Hiatt) Dillon was related to Levi Coffin of Indiana, unofficial President of the Underground Railroad.

Absalom was well-known for his boldness and courage. On one occasion hunters had intercepted his group and began taking them back south out of the county and down to Springfield. Absalom galloped after them and caught up with them at the Sangamon River and with blazing pistols in both hands drove off the hunters and rescued the escaping slaves. According to Charles C. Chapman, on another occasion, in 1827 Absalom joined a party of settlers – including Johnson Sommers and William Woodrow – who set off to rescue the family and friends of Moses Shipman, who were free blacks living in Elm Grove Township whom slavers had kidnapped with the intention of selling them into slavery. Moses gnawed through his ropes and made it back to Elm Grove, where he roused the settlers to his plight. The party caught up with the slavers on a wharf at St. Louis – Absalom picked up a very large rock and threatened to smash the skulls of anyone who dared interfere with the rescue.

After three years in the Missouri courts – with Absalom’s brother Nathan laboring steadfastly to get Moses’ family and friends back to Tazewell County – Moses’ wife Milly and their children were successfully returned to their homes. This was before the formal establishment of the Underground Railroad lines in Tazewell County. Absalom and Nathan and their families are buried in Dillon Cemetery, north of Dillon on Springfield Road.

From Dillon, freedom-seekers would be sent on the Tremont-area U.G.R.R. stations, which included Matthews station, Logan station, Jones station, and Kingman station:

John Albert Jones (1806-1888) of Tremont was editor of the Pekin Gazette in the 1830 and served as Clerk of Tazewell County Circuit Court from 1837 to 1857. It was during his time as clerk that Abraham Lincoln was involved in his first legal case involving slavery — Bailey v. Cromwell in July 1841, which confirmed the freedom of Nance Legins-Costley of Pekin and her three eldest children. Jones’ old mansion — the Jones-Menard House at 412 E. South St., Tremont — still stands, the last remaining U.G.R.R. station in Tazewell County. Freedom-seekers were sometimes sheltered in the house, but more usually Jones used land further out in the county. He is buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield.

Freeman Kingman (1799-1879) of Tremont is recorded in Chapman’s 1879 Tazewell County history as active on the Railroad, and is said to have hidden escaping enslaved persons in the hayloft of his barn. His close neighbors the Briggses, however, were vehemently pro-slavery. Kingdom is buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, Tremont.

Another Tremont-area U.G.R.R. conductor was Peter Logan (c.1780-1866), who was the first formerly enslaved individual to own land in Tazewell County. On Juneteenth in 2025, a new Illinois State Historical Society marker was dedicated. The marker, which tells Logan’s life story, has been placed on the south side of a rural county road, Franklin Street, a short distance west of Springfield Road, very close to the former site of Logan’s homestead. Logan lived there with his sister Charlotte Hurst and Charlotte’s daughter Nancy. Old pioneer memories of Logan related that he was given the chance to buy his own freedom, and then proceeded to raise enough money to buy his sister’s and niece’s freedom too. They arrived in Tazewell County around 1833. Four years after that, Logan had raised enough money to buy his own land in Elm Grove Township, a home lot in Section 22 where the new ISHS marker has been placed, and a timber lot in Section 29 to the southwest of his home lot. Significantly, bordering Logan’s timber lot in Section 29 was another remote timber lot owned by the Lovejoys — ideal locations to help freedom-seekers hide from slave hunters.

After the death of Logan’s sister Charlotte in 1857 (she is buried in Dillon Cemetery a few miles south of Logan’s former farmstead), Logan moved to Peoria, where he died in 1866 and was buried in Peoria’ Old City Cemetery. Logan’s will named Peoria abolitionist Moses Pettengill as the executor of his estate, which was left to Logan’s sole heir, his niece Nancy.

Chapman’s 1879 Tazewell County history relates the following anecdotes regarding the U.G.R.R. activities of Josiah Matthews of rural Tremont:

“The main depot of the U. G. Road in Elm Grove township was at Josiah Matthews’, on section 24. Mr. Matthews was an earnest anti-slavery man, and helped to gain freedom for many slaves. He prepared himself with a covered wagon especially to carry black freight from his station on to the next. On one occasion there were three negroes to be conveyed from his station to the next, but they were so closely watched that some time elapsed before they could contrive to take them in safety. At last a happy plan was conceived, and one which proved successful. Their faces were well whitened with flour, and with a son of Mr. Matthews’ went into the timber coon-hunting. In this way they managed to throw their suspicious neighbors off their guard, and the black freight was safely conducted northward.

“One day there arrived a box of freight at Mr. Matthews’, and was hurriedly consigned to the cellar. On the freight contained in this box there was a reward of $1,500 offered, and the pursuers were but half an hour behind. The wagon in which the box containing the negro was brought was immediately taken apart and hid under the barn. The horses, which had been driven very hard, were rubbed off, and thus all indications of a late arrival were covered up. The pursuers came up in hot haste, and, suspecting that Mr. Matthews’ house contained the fugitive, gave the place a very thorough search, but failed to look into the innocent-looking box in the cellar. Thus, by such stratagem, the slave-hunters were foiled and the fugitive saved. The house was so closely watched, however, that Conductor Matthews had to keep the negro a week before he could carry him further. This station was watched so closely at times that Mr. Matthews came near being caught, in which case, in all probability, his life would have been very short.”

Moving north out of Elm Grove Township, the next U.G.R.R. stations in Morton Township were those of Uriah Crosby and the family of Daniel Roberts and his sons and grandchildren. Chapman records the following U.G.R.R. anecdotes about Crosby and John M. Roberts — including the same sad story that is told in the Bloomington Pantagraph article shared above:

“Mr. Uriah H. Crosby, of Morton township, was an agent and conductor of the U.G.R.R., and had a station at his house. On one occasion there was landed at his station by the conductor just south of him, a very weighty couple, — a Methodist minister and wife. They had a Bible and hymn book that they might conduct religious exercises where they found an opportunity along the way. On conducting them northward Mr. Crosby was obliged to furnish each of them an entire seat, as either of them were of such size as to well fill a seat in his wagon. The next station beyond was at Mr. Kern’s, nine miles. He arrived there in safety, and his heavy cargo was transported on to free soil — Canada.

“The next passenger along the route that stopped at Crosby station arrived on election day. A company had passed on northward when a young man hastily came up. He had invented a cotton gin, and was in haste to overtake the others of the party as they had the model of his invention. He was separated from them by fright. J. M. Roberts found this young man in the morning hid away in his hay-stack, fed him, and sent his son, Junius, with him in haste to Mr. Crosby’s. On his arrival Conductor Crosby put him in his wagon, covered him with a buffalo robe, and drove through Washington and delivered him to Mr. Kern, who took him in an open buggy to the Quaker settlement. He overtook his companions.

“One of the saddest accidents that ever occurred on the U.G. Road in Tazewell county was the capture of a train by slave hunters. Two men, a woman and three children, were traveling together. The woman and children could journey together only from Tremont toward Crosby station, as they had only one buggy. The negro men concluded to walk, but stopped on the way to rest. Waiting as long as they dared for the men to come up, Messrs. Roberts started on with the women and children, but had not gone far before they were stopped by some slave hunters and their load taken from them. The mother and her three children, who were seeking their liberty, were taken to St. Louis and sold, as the slave hunters could realize more by selling them than by returning them to the owner and receiving the reward.

“When the two men came up it was thought best to take them on by a different route, the people determining they should not be captured. J. M. Roberts arranged to take them on horseback to Peoria lake. Several men accompanied them, riding out as far into the water as they could, and by a preconcerted signal parties brought a skiff to them, into which the men were taken and conveyed across the river and sent on the Farmington route in safety. All other routes were too closely watched.”

John M. Robert’s diary includes an entry on an incident in Washington, Illinois, where a pro-slavery mob prevented an abolitionist meeting that had been planned at Washington’s Presbyterian Church, where Rev. Owen Lovejoy had planned to preach:

May 20, 1842: “Mr. M took possession of the Presbyterian Church. Speeches by Elihu Chase and Moffat, Darius, Burton, etc. with swearing ruffians with clubs at the door to keep out all the abolitionists. We left Washington and went to Pleasant Grove. Had a discourse with Mr. Lovejoy and Dicky – 15 or 20 joined the society.”

Chapman in 1879 later told ofthat same incident at greater length as follows:

“In those exciting days of the U.G.R.R. old Father Dickey and Owen Lovejoy, strong anti-slavery men, made an appointment to speak at Washington. On the notice of the meeting being announced the pro-slavery men took forcible and armed possession of the church to be occupied by these speakers, and determined, at all hazards, to prevent the meeting from being held there. A prominent man of conservative views on the slavery question advised the anti-slavery men not to attempt to hold the meeting as they were determined to do, as the mob, he said, were frenzied with liquor, and he feared the consequences. So they concluded to go to Pleasant Grove [Baptist] church, Groveland, where they addressed one of the most enthusiastic anti-slavery meetings ever held in this part of the State. Owen Lovejoy was the orator of the day. The mob were determined to follow and break up that meeting also, but were deterred by being told that as the anti-slavery men were on their own ground they would fight, and doubtless blood would be shed.”

Another occasion of violent opposition to abolitionist activity in Washington was recorded in a letter published in the Western Citizen on 14 Oct. 1842, in which Roswell Grosvenor told of an incident at the Baptist church in Washington: “. . . taking advantage of darkness not to be recognized, [supporters of slavery] prepared themselves with stones or brick bats to give me a salute when I mounted my horse to return home. Several of their missiles took effect – one rather severely in my side; but as no bones were broken, I escaped . . . Yours for freedom of thought, word and action, in the cause of mercy.”

In the face of such opposition, nevertheless Washington Township was the location of the Scott family U.G.R.R. stations. John Randolph Scott (1812-1894) and his brother James Patterson “Uncle Pat” Scott (1805-1866) were two early members of Washington Presbyterian Church. Randolph’s farm was in Section 31, in the southeast corner of Washington Township on the border of Deer Creek Township. Uncle Pat’s farm was just northeast of his brother’s. The Scott brothers were founding members of the Tazewell Anti-Slavery Society. An 1838 letter of Uncle Pat’s says, “We formed a county Anti-Slavery Society about four weeks since and now number nearly 100.” The society then planned the Underground Railroad routes through Tazewell County, with Randolph’s farm as a station.

Referring to her ancestor Patterson Scott, Emma J. Scott’s Early History of Washington says, “Fleeing fugitives found a friend in him, and he not seldom risked his own life and was cited … On one occasion, when he and George Kern were arrested and tried, they were honored by having Abraham Lincoln … to defend them.” That arrest was in 1845.

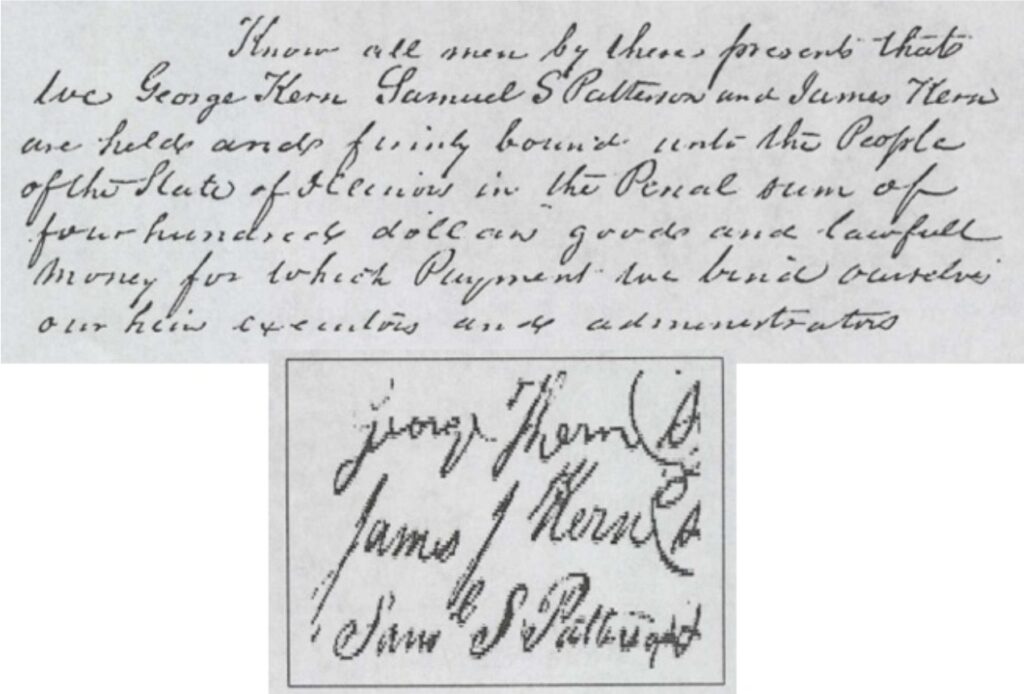

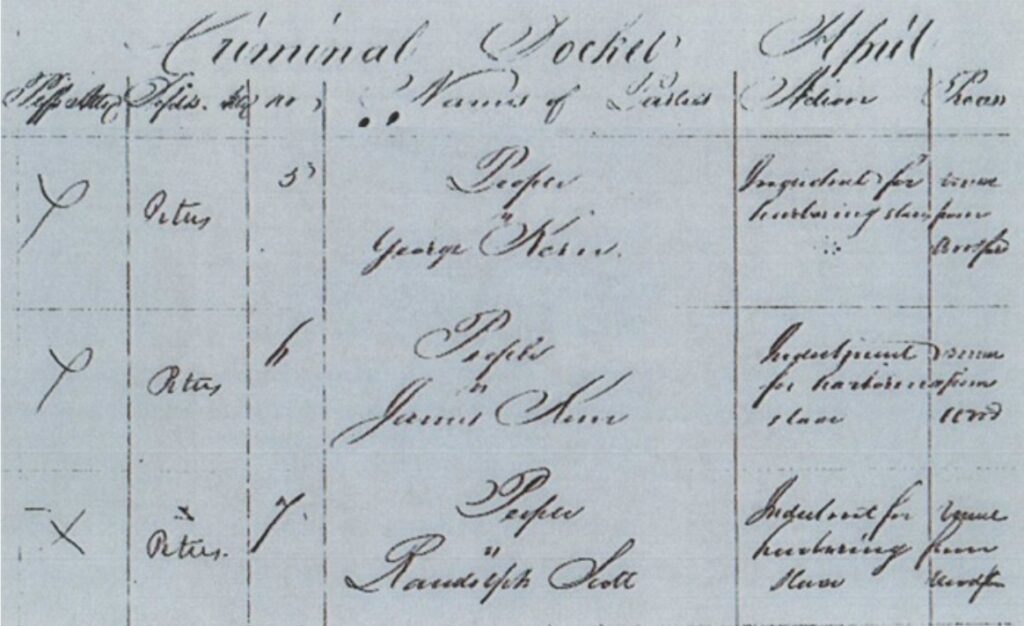

J. George Kern (1799-1883) and his son James J. Kern (1823-1899) of rural Metamora were both active on the Railroad. The Kern farmstead was formerly in Tazewell County, then in Woodford after that county was formed in 1841. The Scotts would send freedom-seekers on to the Kerns. Regarding the episode of the arrest of the Kerns and Randolph Scott, Emma S. Scott says Washington Mayor Andrew Cress had his brother, Thomas Cress, Constable of Washington, arrest George Kern and J. Randolph Scott. Tazewell County Court records show that George’s son James was also arrested. Posting a $400 bond for them was Samuel S. Patterson, shown in 1839 federal land grants as owning farmland in Section 32 of Washington Township, to the east of the farm of J. Patterson Scott. Given the name “Patterson,” the proximity of their farms, and Samuel’s posting bond, it seems probable that Samuel was related to the Scotts.

The attorney for Randolph Scott and the Kerns was Onslow Peters, but the case did not come to trial until the Spring of 1847, when Abraham Lincoln joined their defense. Lincoln Day by Day records the following on 15 April 1847: “George Kern, Sr. and J. Randolph Scott, indicted for aiding fugitive slave, win dismissal of charge when Lincoln argues lack of proof that Negro in case was slave.”

Because the freedom-seeker in question had already made it to Canada, and the person who had enslaved him was not present to testify, the prosecution could not prove its case that the Kerns and Scott had harbored a fugitive. This is believed to be Lincoln’s last legal case involving slavery – six years after Bailey v. Cromwell. Both Tazewell County cases helped to form Lincoln’s attitudes and convictions regarding the immorality and injustice of slavery.