For an older generation, the cold and ice of winter can bring to mind a long-defunct industry that once employed hundreds of men in Pekin – the ice industry. In the days before the invention of the refrigerator, families and business used iceboxes to store food for long periods of time or to keep food from spoiling too quickly. Long-distance transportation of food also required ice-filled train cars, while confectionary businesses needed ice to keep their ice cream cold and their inventory fresh.

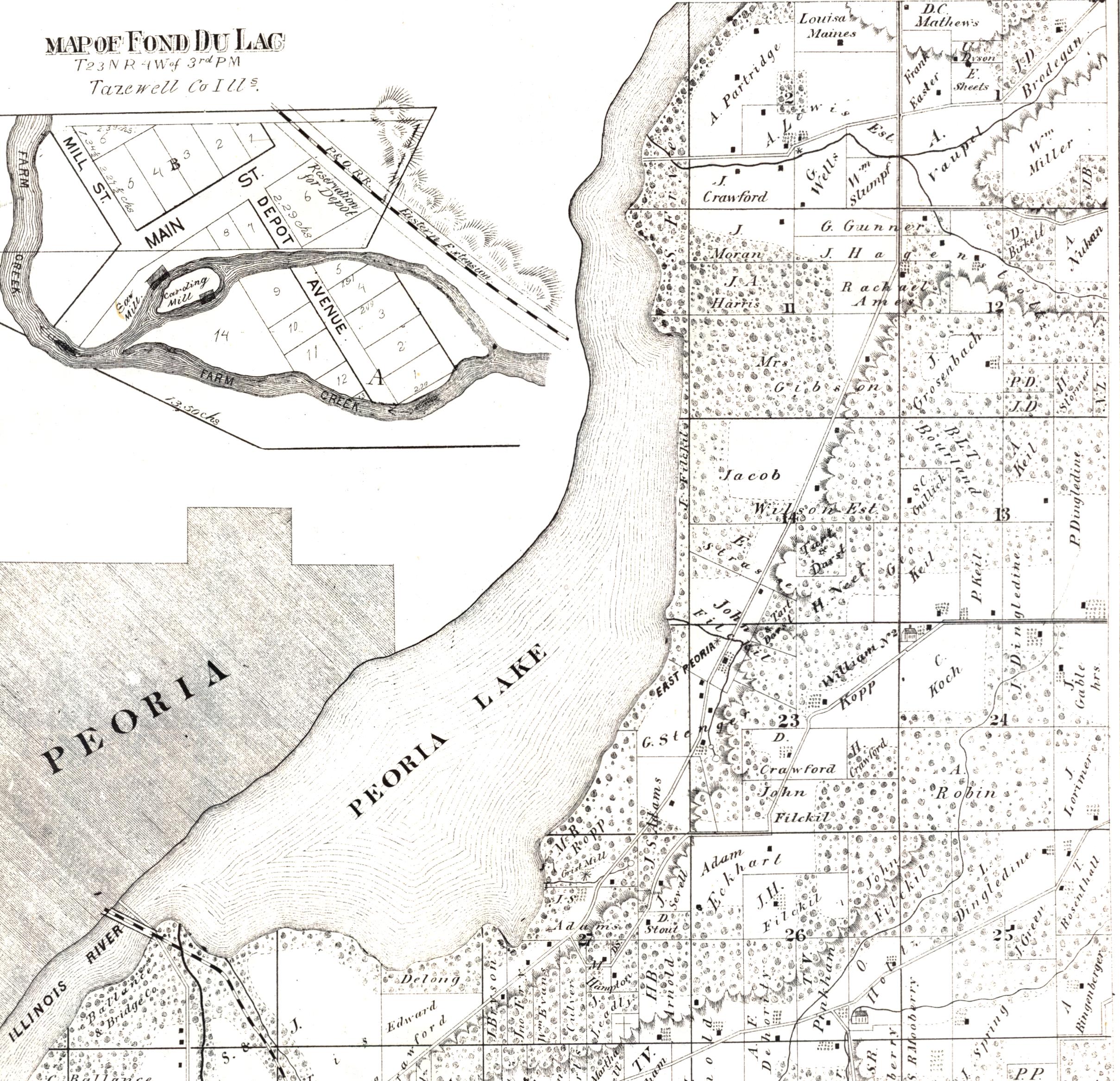

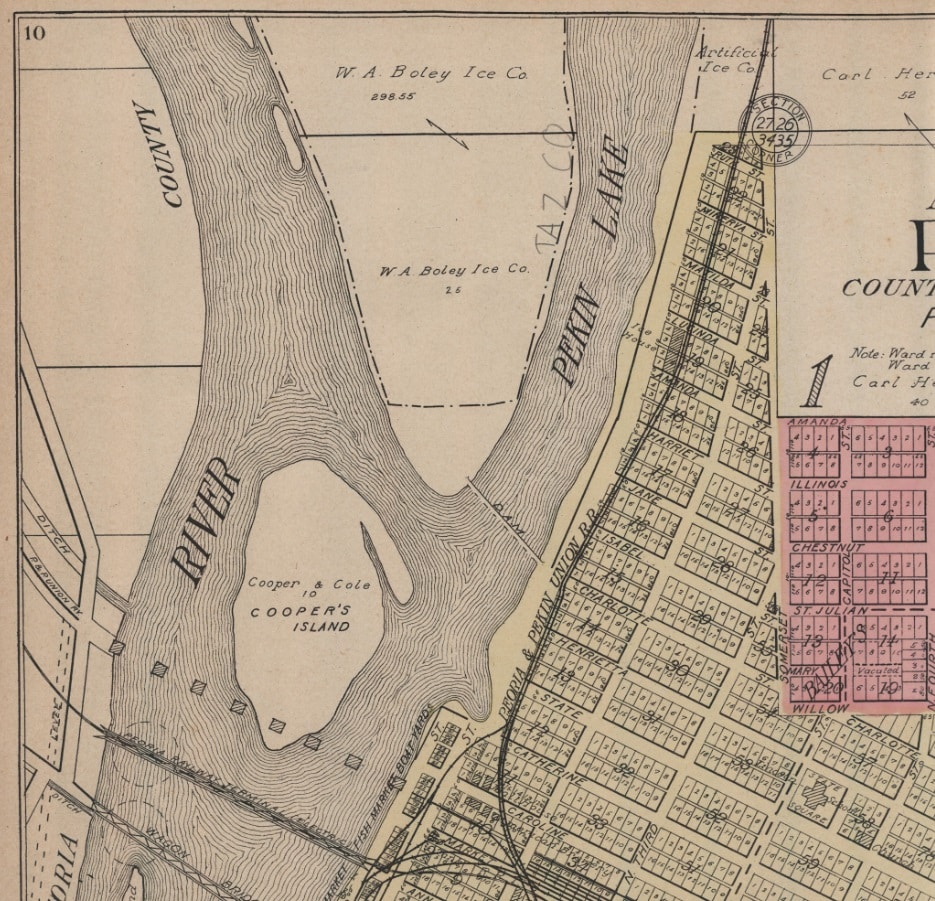

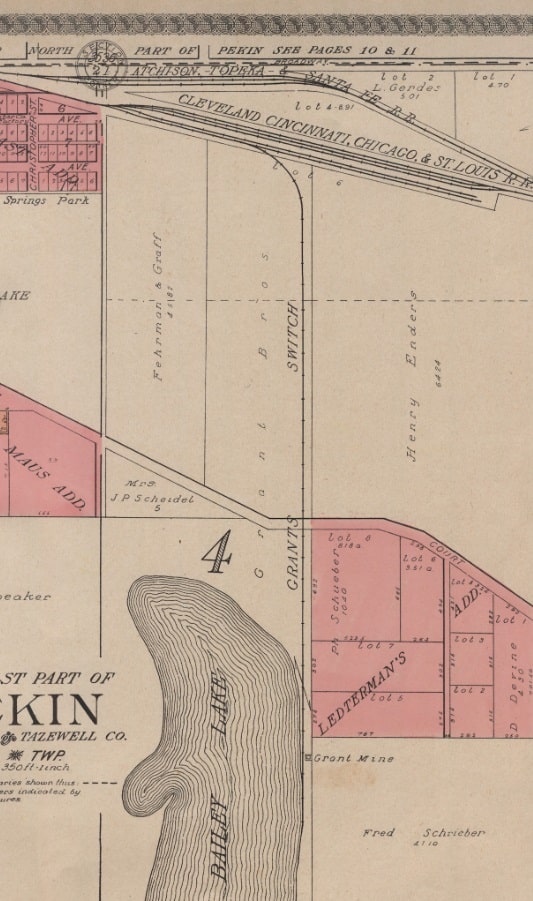

The nationwide demand for ice led to the rise of ice harvesting businesses, and in Pekin the ice industry was exceptionally profitable. Pekin’s riverside location provided it with two ideal locations for the harvesting of ice during the cold winter months: Pekin Lake, and Bailey’s Lake (today’s Meyer’s Lake or Lake Arlann).

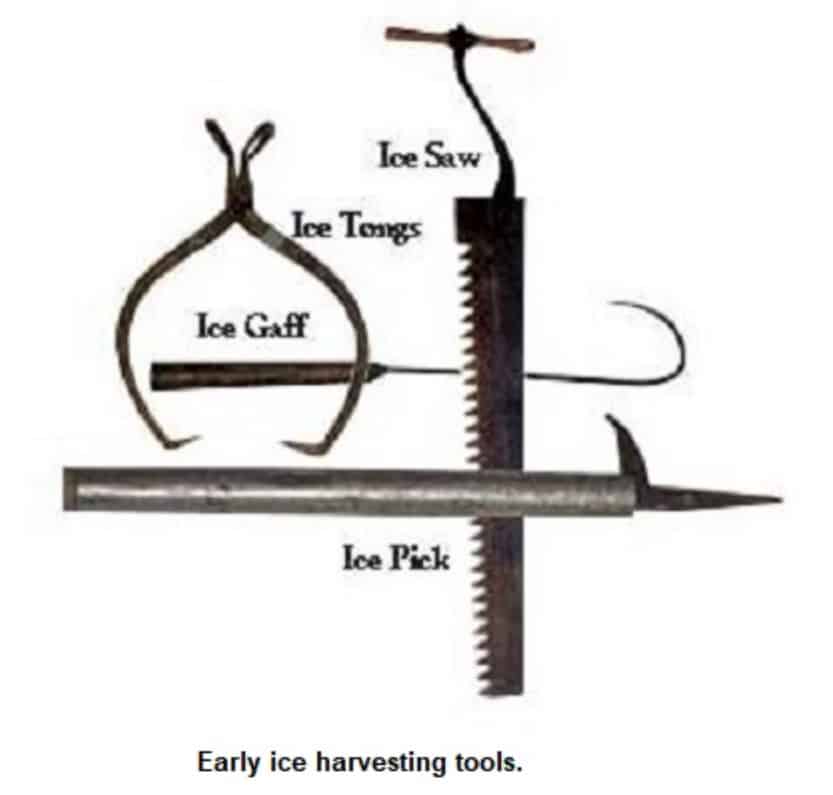

The Madison County ILGenWeb site provides this informative description of the tools and processes used in ice harvesting:

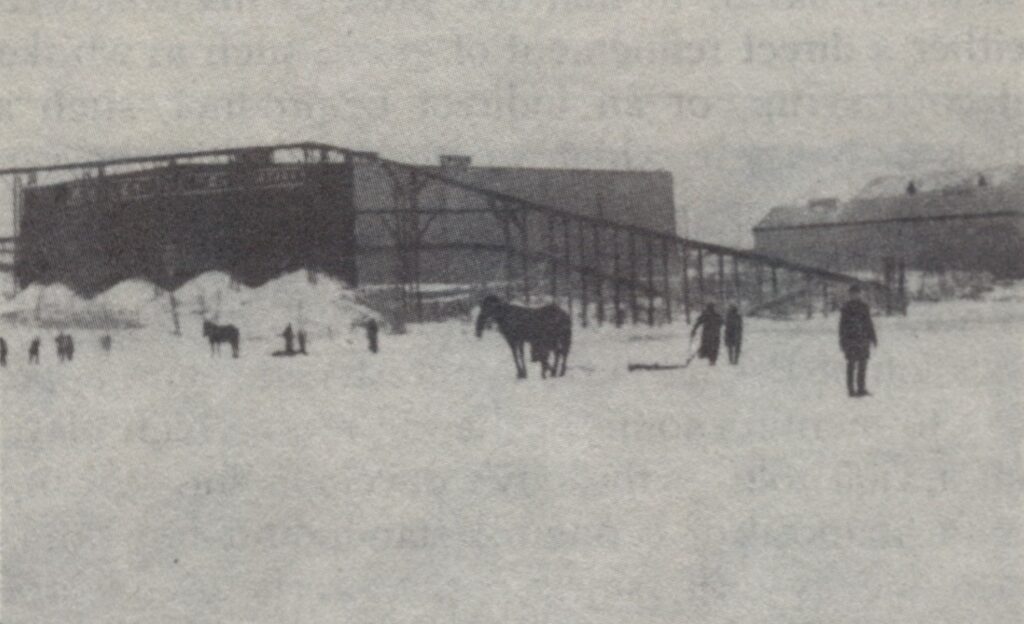

“Early tools for ice cutting were the axe, pick, scraper, the ice saw, and the breaking-off bar (similar to a crowbar). After 1900, the horse-drawn ice marker and ice plow came into use. By 1918, the power field saw was introduced.

“Men gathered on the river and harvested ice for food storage, industries such as breweries and railroads (fresh food was often shipped by rail), and private use. It was labor-intensive work. The first ice houses were constructed underground, and straw was a common insulator. Later, saw dust was used to pack around the ice to prevent melting. Soon ice houses were constructed above ground, and some wealthy residents had their own ice houses on their property. Ice harvesting provided more income for families and a much-needed product.”

Pekin’s ice harvesting is also described in Pekin: A Pictorial History (1998, 2004), page 100, as follows:

“Ice was cut from the river, preserved in storage houses and covered with sawdust, a by-product from cooperage houses and woodworking industries. The ice was delivered door-to-door in horse-drawn wagons.

“Before refrigeration, kitchens were equipped with ice boxes and customers put signs in their windows with either a ‘25’ or ‘50’ facing up to indicate how many pounds of ice they needed that day. The old icebox of treasured memory was an oak affair with fancy doors and sturdy handles that would be appropriate on a ship.

“Sometimes, to save money, men would stop at the icehouse on the way home from work. They would carry a block of ice home on the front bumpers of their cars, which were ‘square and sturdy and commodious.’ During the very hottest summers, as in 1936, ice did not last long even in the insulated icebox. Alternately, housewives in the winter would use a window box utilizing outside air for cooling and freezing. It was a tin compartment that clamped into a kitchen window. Unfortunately, more often than not, the milk in the tin box next morning was frozen.”

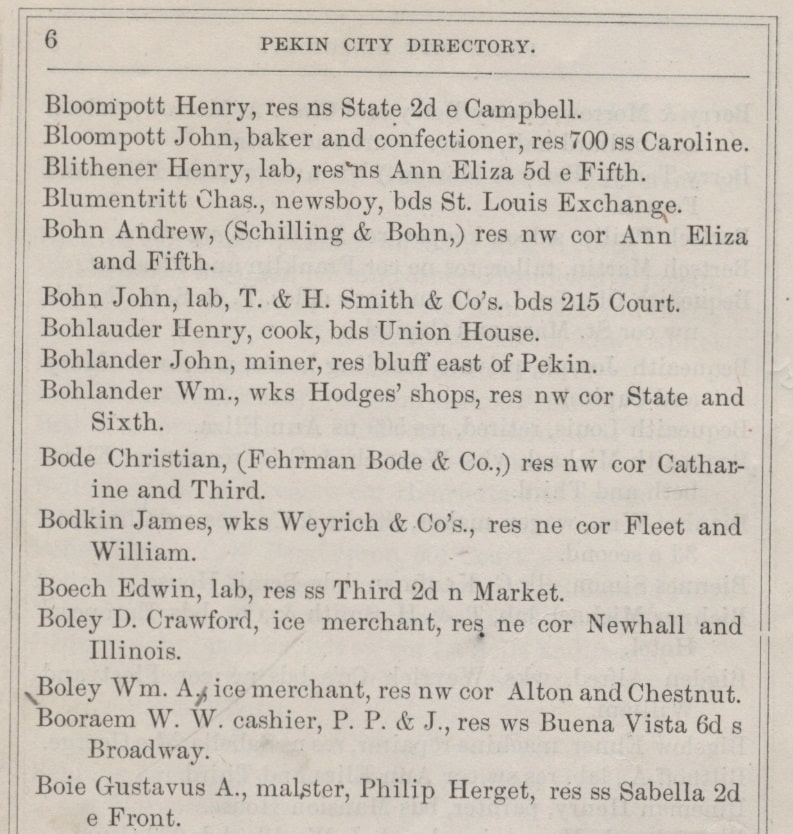

The father of Pekin’s ice industry was an early settler named John Lowry. We know little of Lowry and his ice business, but we know it was located in Pekin during the 1850s and 1860s, and that he was engaged in the harvesting of winter ice from Pekin Lake and shipping it downriver (probably to St. Louis). Lowry’s was not the only ice business in the area, though. Another successful ice harvesting operation, the Memphis Ice Company, was based across the Illinois River and downstream, at Kingston.

The activities of these two businesses form the “prehistory” of Pekin’s best-known and longest-lived ice harvesting firm, which was located on the shores of Pekin Lake: the W. A. Boley Company, the business of William Alexander ‘Alec’ Boley (1832-1895), Pekin’s king of ice. Following are some key excerpts from Boley’s biography that was published in Ben C. Allensworth’s 1905 “History of Tazewell County”:

“William Alexander Boley (deceased) was born in Pittsburg, Pa., January 5, 1832, the son of Daniel and Ruth I. (Crawford) Boley. His father is of German lineage [cf. German name ‘Bohle’], but for generations has been identified with Pennsylvania history, his father, grandfather and great-grandfather all being natives of that State . . .

“William Alexander Boley was reared in his native State of Pennsylvania, received a common-school and academic education and, after the death of his father [1847], assumed the management of the coal business, which he sold out a year later. He then engaged in steam-boating on the Ohio River, for the first three weeks being employed as watchman, when he was promoted to the position of second mate and, five months later, to first mate. In the latter capacity he continued three years, doing duty on boats on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers between Pittsburg, St. Louis and New Orleans. . . .

“He next became superintendent of the Memphis Ice Company, whose headquarters were at Kingston, Ill. In its day this was one of the most prominent concerns of its kind in the State, owning and operating thirteen barges besides a number of tow-boats.

“In 1860 Mr. Boley came to Pekin, Ill., and there accepted a position as superintendent for John Lowrey, which position he retained six years, when he purchased the entire business. In 1888 the concern was incorporated under the name of the W. A. Boley Ice Company, which a capital stock of $32,000, of which Mr. Boley was made the President and General Manager.”

Further information about Boley’s career in ice harvesting is found in his 1895 newspaper obituary:

“. . . In 1855 he was offered the superintendency of the Memphis Ice Co., of Kingston, Illinois, and accepted it. From that day to this he has been identified with the ice industry. In 1860, he became superintendent for John Lowry and a few years later purchased the business he has since conducted, enlarging it and spreading out until today the Boley Ice Co., is known far and wide. Seven years ago, the concern was incorporated with a capital stock of $32,000, Mr. Boley becoming president and manager.”

The 1974 Pekin Sesquicentennial also mentions:

“. . . the ice was shipped down the river on large barges. Pekin Lake’s shore was literally lined with ice houses, built along Gravel Ridge. They were huge affairs, capable of holding some 20,000 tons each. All were owned by the W. A. Boley Company, Inc., who had purchased the business from John Lowry in 1866. Seven years later, the Boley Company bought the lake for $5,000, and retained the exclusive rights (through the Otto Koch Estate) until the early 1950’s . . . .”

Another detail is provided by Boley’s biography in Allensworth’s 1905 Tazewell County history:

“The houses which were owned by the company were situated on Pekin Lake, and had a capacity of 35,000 tons. By means of side-tracks the ice could be loaded in cars and shipped to various points throughout the State.”

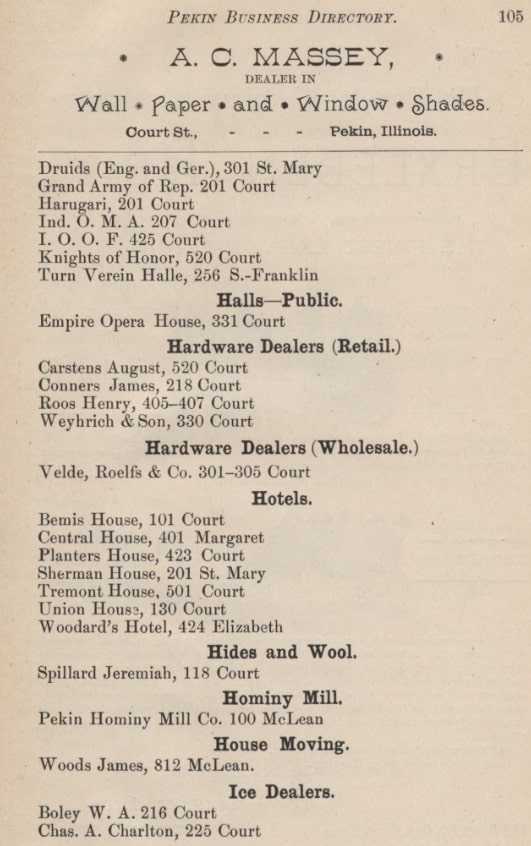

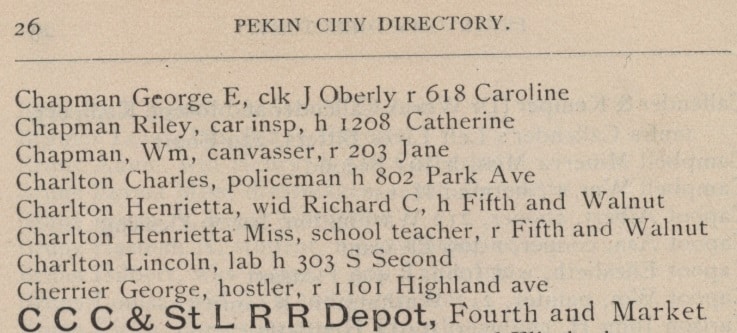

Boley’s ice business made the news in the Tazewell Republican, 30 June 1876, which related this accident involving Boley’s employee Charles A. Charlton (1850-1927):

“Boley’s new grays are a nice team, and they don’t propose to be run over by anybody’s locomotive. Yesterday while Mr. Boley’s teamster was loading ice into a car on the track near the Union depot an engine came running by, frightened the horses and away they started. Mr. Charlton, the driver, tried to get on the step at the rear end of the ice wagon where the reins were tied, but missed his footing and fell. The horses ran about two blocks, the ice bobbed up and down and played a lively game of rolley-bolley, and when the concern was stopped it was ascertained that the damage was a broken tongue and a damaged wheel.”

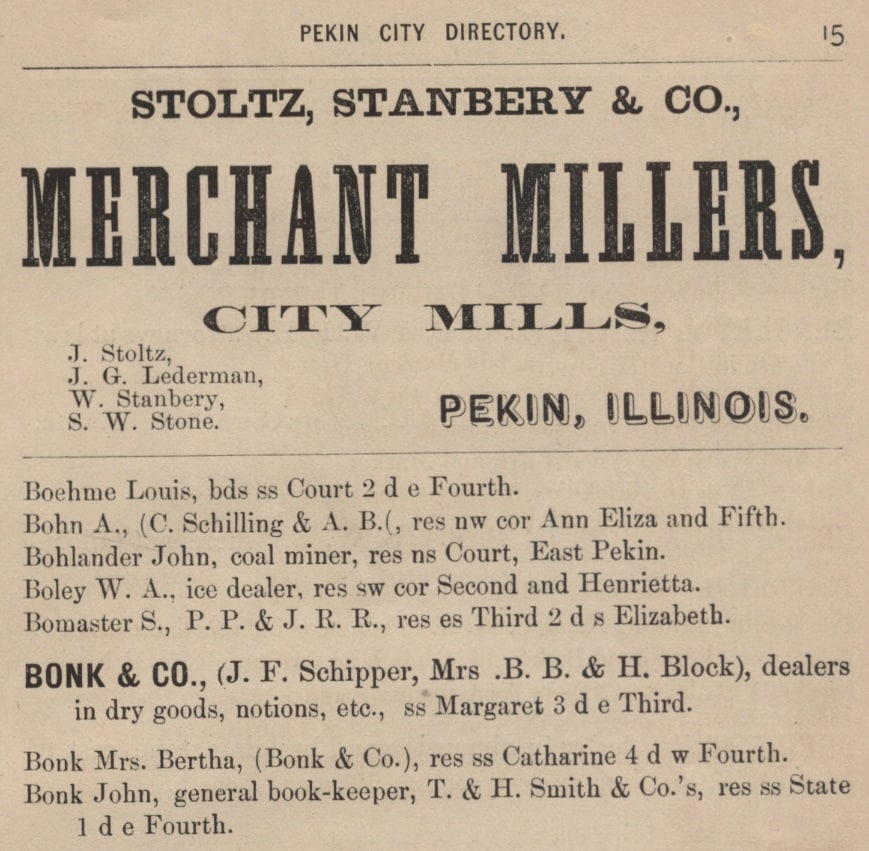

A few years later, Charlton left the W. A. Boley Company and went into the ice harvesting business himself as Boley’s competitor! The Pekin Daily Times, 30 April 1885, includes this advertising article about Charlton’s business, which was located on the shores of Bailey’s Lake:

An Ice Merchant

“One of our most enterprising business men is Mr. Charles A. Charlton. He conducts a general ice business, and we are pleased to state that business is booming with him. The present prospects are unusually bright for a splendid summer trade. His ice house is on east Court street, and it is packed with the finest quality of frozen goods, harvested from Bailey’s lake, which is made up entirely of spring water. The ice is, therefore, as clear as crystal. The quality is superior to any other gathered. Mr. Charlton does a wholesale business in central Illinois, as well as the largest retail trade in the city. All orders left at his down town office will receive prompt attention.”

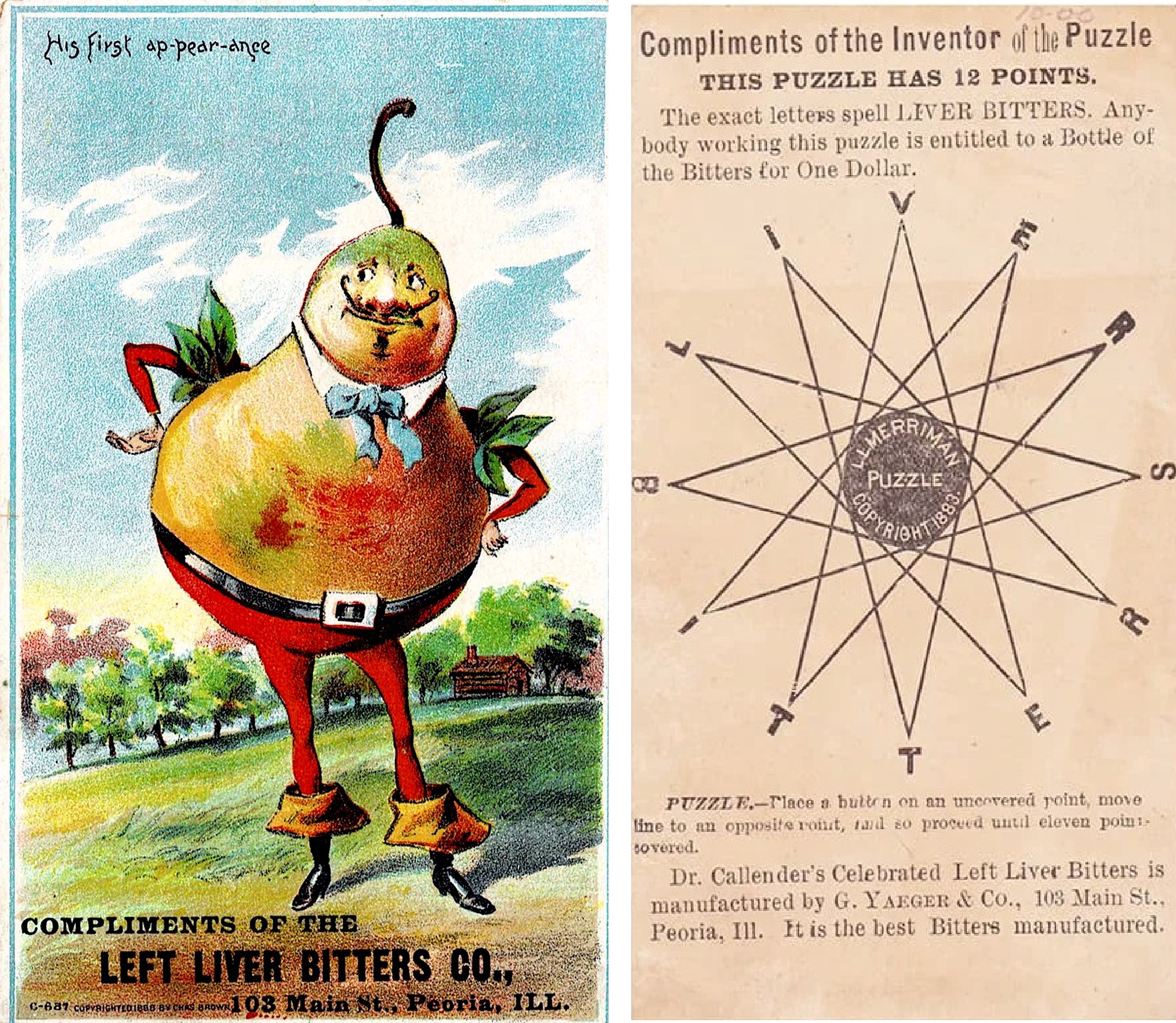

Further insight into Pekin’s ice harvesting, and the ice industry in general, is found in a article titled, “Ice cutters harvested ‘crystal treasure’ from lakes, ponds” (Bloomington Pantagraph, 10 March 2013), by Bill Kemp, archivist and historian for the McLean County Museum of History:

“In late 1882, Monroe Brothers sold their business (including the ice-cutting surface of a mill pond near Kappa) to the W.A. Boley Ice Co. of Pekin, a large concern with operations in St. Louis and Evansville.

“By the 1880s the natural ice industry was finding it increasingly difficult to compete against the newly developed industrial process of manufactured ice. Unaffected by the vagaries of wintertime freeze-and-thaw patterns, ‘factory-made’ ice was also seen as a ‘sanitary’ alternative to a supply too-often culled from the polluted waters of Industrial Age America. Not incidentally, Bloomington’s first manufactured ice plant opened sometime in the early 1890s.

“Even so, natural ice was still harvested locally on a commercial scale for another decade or more. ‘The ice cutters are busily engaged in cutting, hauling and storing away their crystal treasures,’ noted The Pantagraph of Jan. 2, 1893. ‘Natural ice is largely used yet, especially by butchers, brewers and other persons, or establishments who make use of large quantities.’”

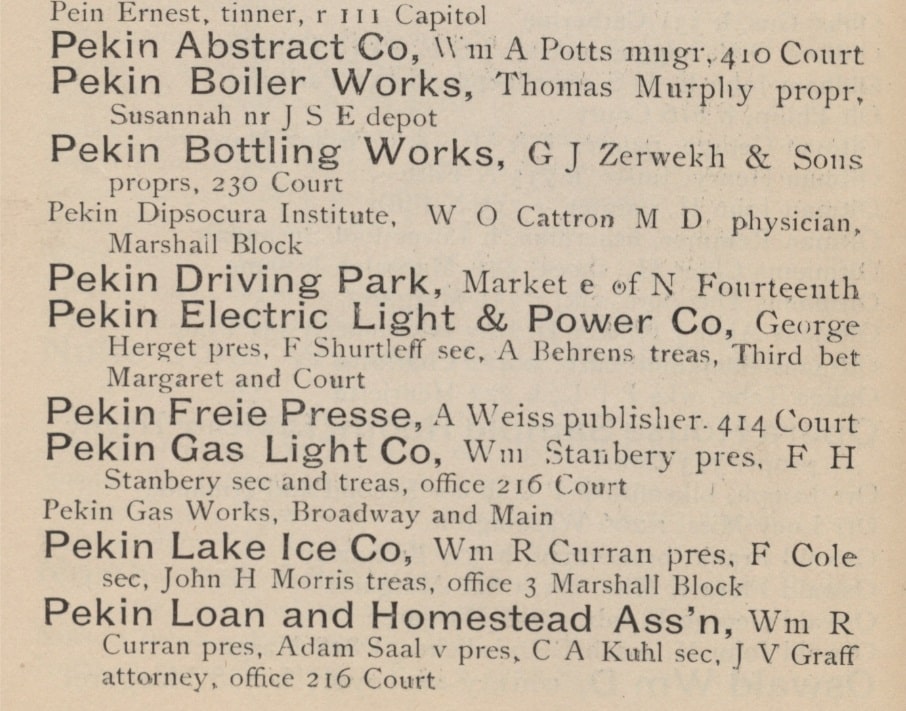

Charles Charlton’s ice business on Bailey’s Lake did not last long. By 1893 he was out of the business altogether, and had joined the Pekin Police Department (and by 1895 he had become the Chief of Police). But the 1893 Bates City Directory of Pekin also shows that Boley had a new competitor: attorney and judge William Reid Curran (1854-1921), president of the Pekin Loan and Homestead Association. But Curran’s stint as an ice merchant was even shorter than Charlton’s. By 1895, the Bates City Directory shows the W. A. Boley Ice Company of Pekin as Pekin’s only ice dealer. However, that same year Boley passed away.

This is the account of Boley’s death from his Pekin Daily Times obituary, which also offered a tribute to Boley’s character and contribution to his community:

“Born January 5, 1832, died February 13, 1895, at his home in this city, aged 63, 1 month and 8 days, came the end of a busy and useful life . . . The sickness, which yesterday resulted in death, is of long standing. For years, he has been a martyr to stomach trouble, suffering frequent attacks, that would confine him to bed for several days at a time. The last attack came on about ten days ago in the form of a hemorrhage of the stomach, and his condition at once became alarming. This was followed by other hemorrhages, until at last, worn out and weakened beyond further endurance, he closed his eyes in eternal sleep and passed peacefully away to that mysterious borne from whence no traveler e’er returns.

“Yes, W. A. Boley, the dutiful husband, the kind father, the faithful friend, is dead, but the memory of his kindly deeds, his open-handed charity will live long years to come. No man was more generous than Alec Boley. No man performed more acts of practical Christianity than Alec Boley. His heart was as big and as full of kindness and tenderness as beats in the bosom of any man and the poor whom he had befriended will not soon forget him. He was a man of deeds, not of words, and preferred to keep his kindly acts in the back ground, rather than let them be known . . . .”

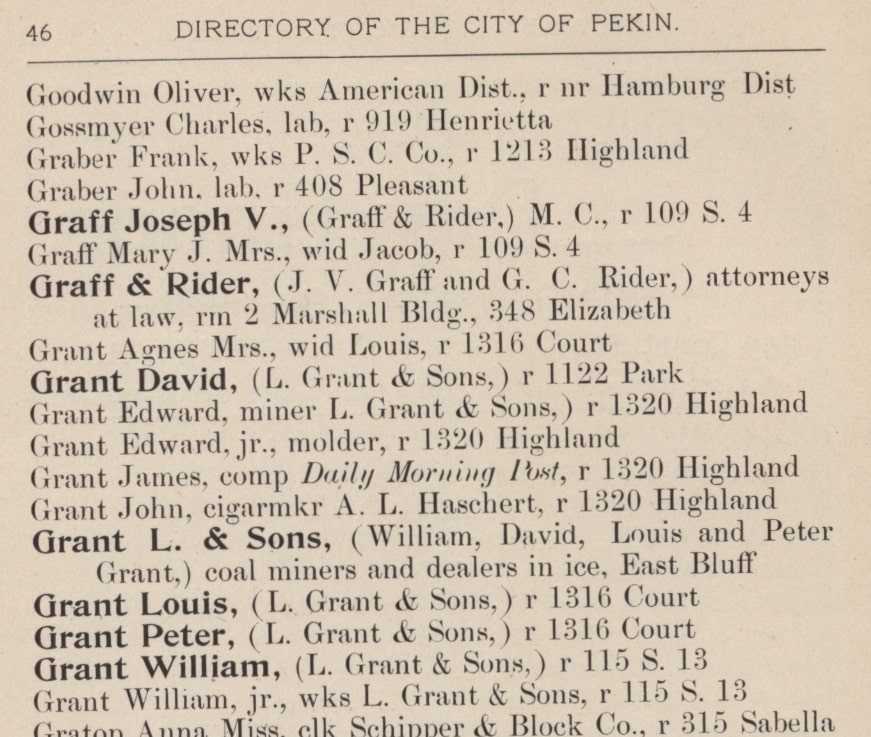

After Boley’s death in 1895, his vice president and manager Otto Koch (1849-1928) took over as president and general manager. But by 1898, the directory shows new competitors: Lewis (Louis) Grant (1867-1947) and sons, coal miners on the bluffs of Bailey’s Lake — successors of Charlton and Curran. Grant Bros. were formidable competitors, because they could rely on their coal mining income to tide them over from winter to winter.

Here is the 1974 Pekin Sesquicentennial’s account of the Grant family’s ice business:

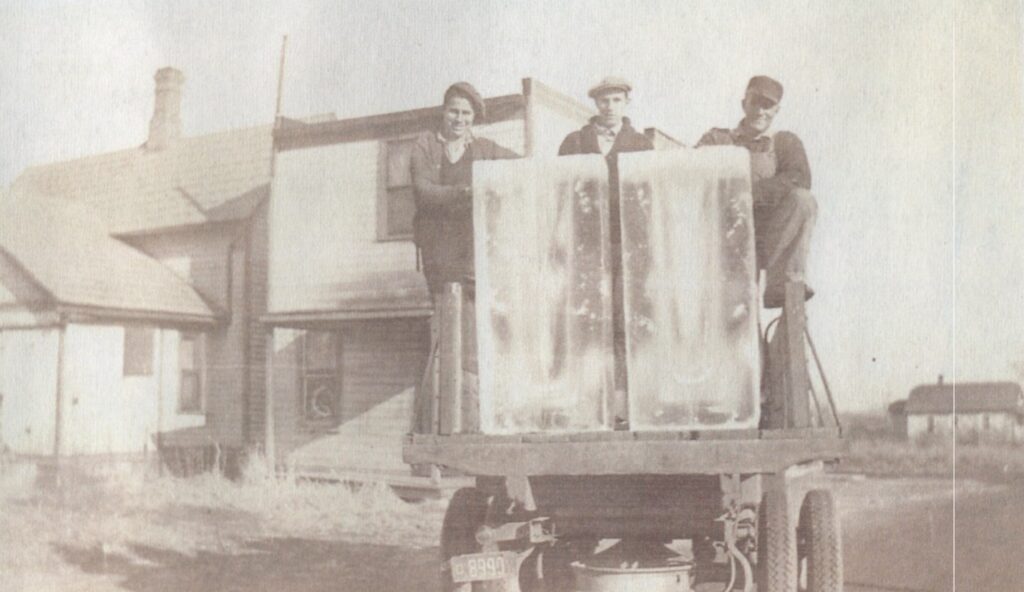

“During the height of the season, it is reported that the Grant Company employed as many as 300 men to cut and load the ice. As many as five box cars per day were loaded by hand, and the cakes of ice weighed as much as 170 pounds each.

“Ice could be stored for as long as two years, through a process which involved packing the frozen water in straw and sawdust. When ice was taken from the storage houses for delivery to homes and businesses in the summer months, it had to be sawed and chiseled into 25, 50, and 100 pound cakes. Customers would have a card in their front window, indicating to the delivery man how much, if any, ice was needed. Children used to follow the ice man around as if he were the Pied Piper, hoping to catch him in a generous mood and have him give them a small piece; it may have been a far cry from air conditioning, but it was a great way to cool off on a hot day before 1930.”

Late springtime storms in 1911 dealt the W. A. Boley Company suffered a serious setback, as we read in this report rom the Idaho Statesman, 29 May 1911:

TWO BOYS KILLED BY A TORNADO IN ILLINOIS, Storm Strikes Pekin and Causes Property Loss of Thousands of Dollars

Peoria Illinois, May 28 — A tornado struck Pekin Illinois, 10 miles south of here, at 1 o’clock this afternoon, killing two persons and causing property damage that will amount to thousands. The dead: Clyde Sakers, aged 14, Frank Woodley, aged 15. The storm came from the south-west, demolishing the pumping station on the east bank of the Illinois river. It then jumped across the Illinois River and the plants of the Boley Ice company were completely destroyed. The residence portion of the city escaped. Wire communications of all kinds are demolished.

Yet another severe setback hit the Boley ice company on 1922, when many of their ice houses were destroyed in a fire. The following article, “Fire Destroys Ice Houses of Boley Company,” was published in an unknown newspaper on 28 Oct. 1922:

“Ice houses of the Boley Ice Company were totally destroyed by a disastrous fire last evening about 6 o’clock. The houses were what are known as the lower houses and there was no ice in them. It is believed that the fire was started by sparks from a train and it gained great headway before an alarm was turned in.

“The fire department had just returned from a small fire in the neighborhood of the sugar works, and ‘fire out’ had just been tapped, when the ice house alarm came in. The department was handicapped by the great headway the blaze had attained before their arrival and there was no hope of saving the structure.

“The fire spread rapidly, the huge flames which leaped into the air being plainly seen for miles. One or two residences across the track from the burning buildings were slightly scorched and a great throng was attracted to the fire.

“The Boley company will suffer a heavy loss, the insurance on the buildings being sufficient to only partially cover it.”

End of an era: Boley hands the baton to Stark

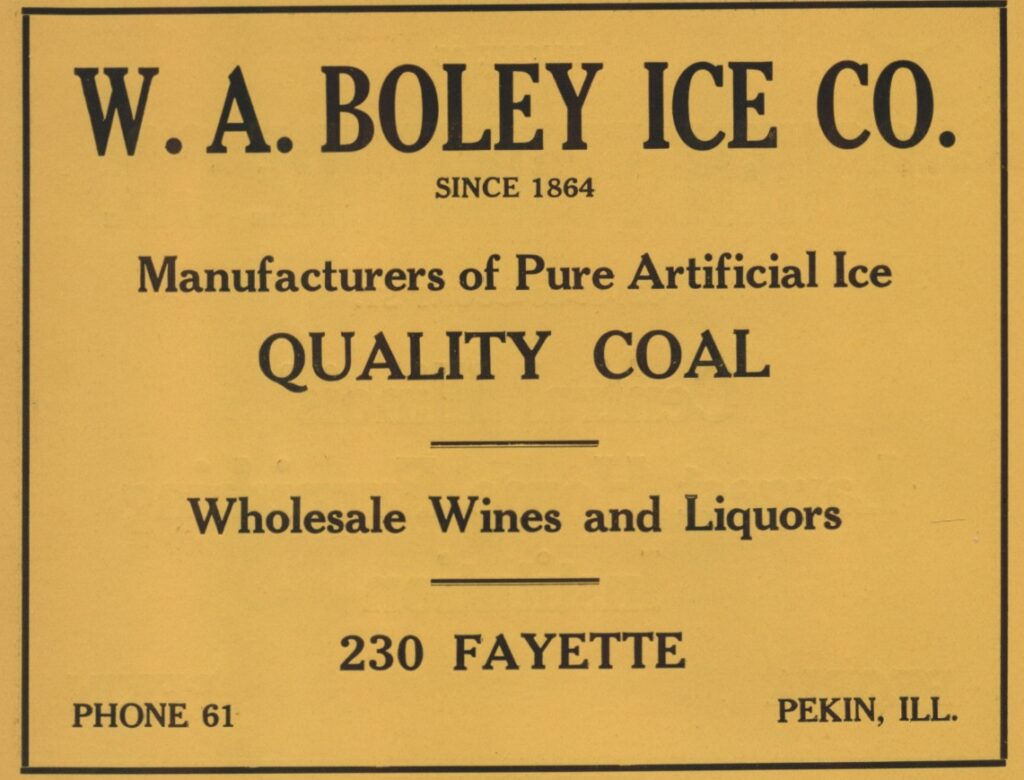

Boley’s final competitor, C. Stark & Son Ice Company, arrived on the scene in 1932, with offices at 304 Margaret. By 1937, Boley had gone out of business. Stark moved into Boley’s storage house at 230 Fayette while also running a site at 304 Illinois. Even after the demise of W. A. Boley Ice Company, the ownership of Pekin Lake remained with Otto Koch and his heirs until the early 1950s. Afterwards, says the 1974 Pekin Sesquiscentennial, “it was purchased by the Forest Park Foundation who donated it to the state for recreational purposes.”

C. Stark & Son Ice Company would prove to be Pekin’s last ice dealer, supplying ice to residences from the 1930s until the early 1950s. “Stark” was Chris Stark (1878-1957) and “Son” was Carl Stark (1901-1951). In the early 1940s, the company’s manager was Oscar C. Curtis, and among their ice men were John Urish and Oscar Jackson. Another of the Stark ice men was Ellwood “Woody” Lawson (1926-2010), who hired on at age 17 and learned the ropes of ice work from Urish.

The Stark Ice Company went out of business around 1943 due to a fire caused by welding torches during renovation work. The fire destroyed their building on Illinois Street, and the Stark family then sold their business to the Peoria Ice Company. World War II was raging during those years, and several of the former Stark ice men went off to fight, including young Woody Lawson.

After the war, Lawson again found work as an ice man in Pekin, this time with City Coal & Ice. But the increasing popularity and affordability of the refrigerator around the middle of the twentieth century soon put an end to the old ice industry. In the 1950s, Lawson ended his years in the ice industry with the distinction in local history of being Pekin’s last residential ice deliveryman.