The first 19 years of Pekin’s history cover the period when our community was a pioneer town — an unincorporated community until 1835 (or 1837), and as a self-governed incorporated Town from the mid-1830s until 1849.

During those first decades, Pekin had much of the character that is associated with the Wild West rather than a modern semi-rural Midwestern city. A Native American village even thrived near the new town until 1833, first located on the ridge above Pekin Lake and later on the south shores of Worley Lake.

However, as Pekin’s pioneer historian William H. Bates tells in the 1870-71 Pekin City Directory, it was in that first period of Pekin’s history that the crucial groundwork was laid for Pekin’s civic development.

Thus, Bates tells us that Pekin’s nascent economy got a boost in Pekin’s first year with the opening of two stores – one belonging to Absalom Dillon and the other to David Bailey – and a hotel or tavern operated by Pekin co-founder Gideon Hawley. Religion in the new town also made its debut in 1830, with the construction of Rev. Joseph Mitchell’s Methodist Church on Elizabeth Street between Third and Capitol.

The following year, Thomas Snell built the town’s first school house, located on Second Street between Elizabeth and St. Mary. Thomas’ son John was the school teacher. The same year, Thomas built Pekin’s first warehouse.

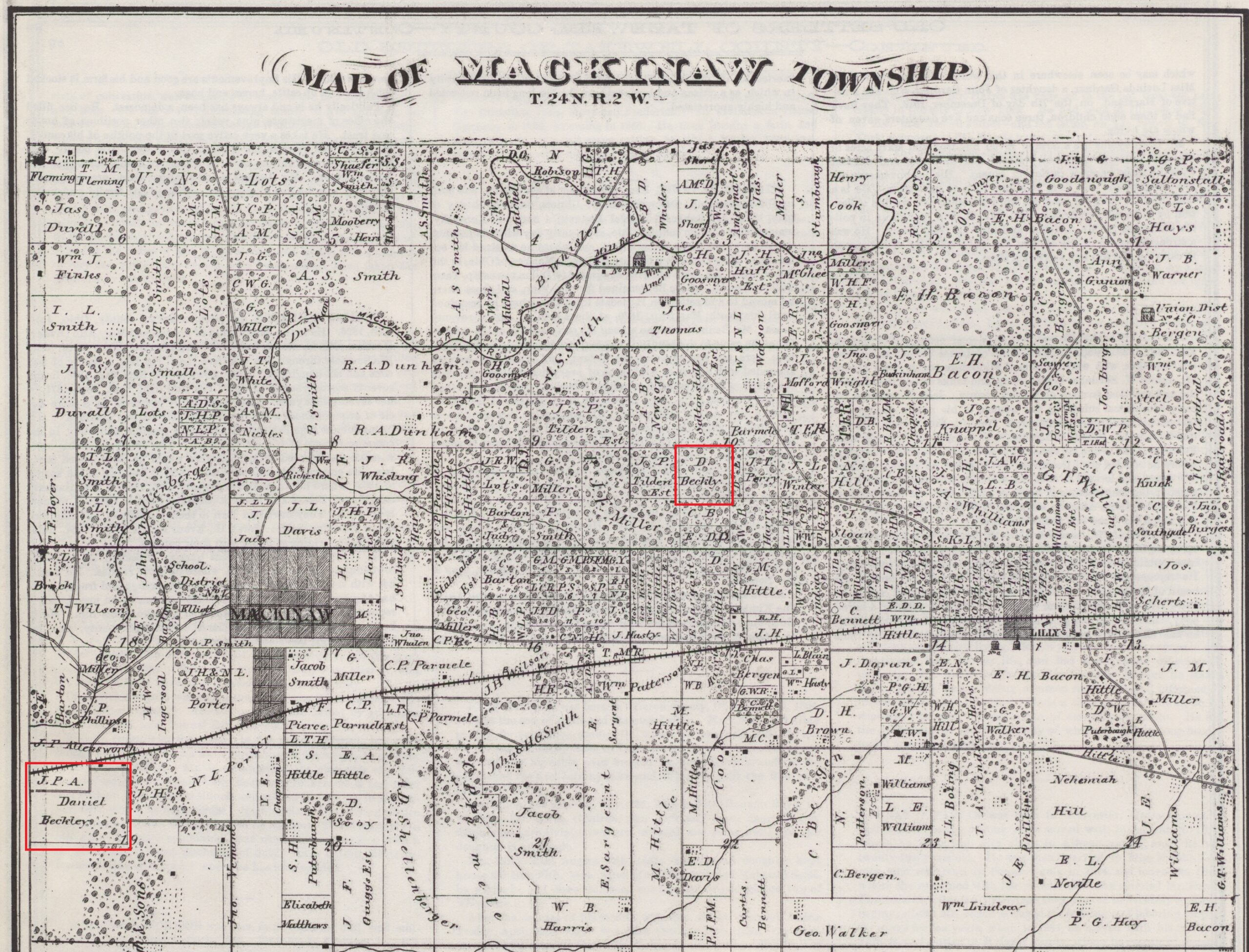

The most significant of 1831’s milestones for Pekin was the transfer of the county seat from Mackinaw to Pekin. When the Illinois General Assembly created Tazewell County in early 1827, Mackinaw was designated as the county seat because it was near what was then the geographical center of Tazewell County. But Pekin’s location as a port on the Illinois River meant Pekin was less remote than Mackinaw. That greater accessibility gave Pekin better prospects.

Another thing that may have played a role in the decision to move the county seat was a memorable extreme weather event: the incredible “Deep Snow” of Dec. 1830, a snowfall and sudden freeze that had turned life on the Illinois prairie into a desperate fight for survival. Pekin was closer to other, larger towns and settlements than Mackinaw, and therefore safer for settlers.

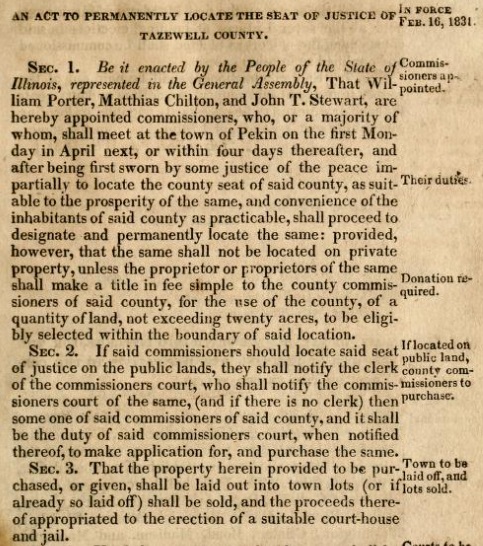

With such considerations in mind, the county’s officials found it more convenient to meet in Pekin, and soon sought permission from the state to relocate the county seat to Pekin. On 18 Feb. 1831, the Illinois General Assembly enacted a law that created a special county commission to choose a new county seat. The appointed Commissioners were William Porter, Matthias Chilton, and John T. Stewart. The law directed the Commissioners to meet in Pekin on the first Monday of April 1831, or within four days of that date, to confer and choose a permanent seat of government for Tazewell. Section 4 of the law stipulates:

“Until the county seat of said county shall be located, it shall be the duty of the county commissioners court to to procure a suitable house at Pekin, and the several courts shall be held at Pekin until suitable buildings are furnished at the county seat.”

Pekin remained the county seat for the next five years. During that time, Illinois Supreme Court Justice Samuel D. Lockwood presided over the Circuit Court in Tazewell County. Court at first took place in the Snell school house, but later would convene in the Pekin home of Joshua C. Morgan, who simultaneously held the offices of Circuit Clerk, County Clerk, Recorder of Deeds, Master in Chancery, and Postmaster. That house was later the residence of Pekin pioneer doctor William S. Maus.

Another notable event of Pekin’s early history that greatly aided in transportation and trade was the surveying and laying out of a state road from Pekin to Mackinaw and beyond. The General Assembly passed a law on 10 Feb. 1831 that appointed William Orendorff of McLean County and Matthias Reinhart of Vermilion County as road commissioners with the authority to lay out the new state road, which was to begin in Pekin and extend to Mackinaw, then to Blooming Grove (McLean County’s first settlement, located in Bloomington Township), then to Cheney’s Grove, and to end at Big Grove in Vermilion County (today known as Champaign in Champaign County). Part of this old state road is ancestral to Illinois Route 9 from Pekin to Bloomington, though the route it follows varies from what it originally did.

The Black Hawk War, Illinois’ last conflict with its Native American population, broke out in 1832. The war lasted only a few months. It began disastrously for the Illinois militia with the debacle at Stillman’s Run in northern Illinois, where the untrained and undisciplined militia recruits quickly succumbed to panic and fled, leaving behind the few brave men in their number to be butchered and scalped. As Bates sardonically put it, “The balance of the command, so history hath it, saved their scalps by doing some exceedingly rapid marching to Dixon on the Rock River.” Among the fallen was Pekin co-founder Major Isaac Perkins.

The town of Pekin itself was not directly affected by the fighting, although the townsfolk did build a stockade around the Snell school house as a precaution, renaming it Fort Doolittle. The fort never had to be used, however, which was a very good thing, because, as Bates commented, it “was so constructed, that in case of a siege, the occupants would have been entirely destitute of water.”

Despite the war’s inauspicious start, the Illinois troops quickly gained the upper hand and Sauk war leader Black Hawk (Makataimeshekiakiak) was forced to give up the struggle. The outcome of the war was the greatest calamity for the remaining Indian tribes of Illinois, who beginning in 1833 were almost to the last man, woman, and child relocated to reservations west of the Mississippi – including the Pottawatomi and Kickapoo bands who lived in Tazewell County. Tazewell County’s Pottawatomi were soon joined by the harried remnants of their kin from Indiana, whom state militia soldiers forced to march west from their homes in Indiana in 1838 along a route that is remembered as the Pottawatomi Trail of Death.

In July 1834, an epidemic of Asiatic cholera struck Pekin, causing the deaths of several pioneers, including Thomas Snell and the wife of Joshua C. Morgan. The victims were hastily interred in the old Tharp Burying Ground, the former site of which is now the parking lot of the Pekin Schnucks grocery store.

Given the challenges and upheavals of the first five years of Pekin’s existence, it should not be surprising that, as we mentioned before, the crucial 2 July 1835 vote to incorporate as a Town failed to be legally recorded. On July 9, 1835, the townsfolk elected five men as Trustees: David Mark, David Bailey, Samuel Wilson, Joshua C. Morgan, and Samuel Pillsbury. Two days later, Pekin’s newly elected Board of Trustees organized itself, choosing Morgan as its president and Benjamin Kellogg Jr. as clerk.

One of the first acts of the new board was passing an ordinance on 1 Aug. 1835, specifying the town’s limits. At the time, Pekin’s boundaries extended from the west bank of the Illinois River in Peoria County eastward along a line that is today represented by Dirksen Court, reaching out as far as 11th Street, then straight south along 11th to Broadway, then westward along Broadway back across the Illinois River to Peoria County. It is noteworthy that land in Peoria County has been included within the limits of Pekin ever since 1835.

Pekin’s first Board of Trustees continued to meet until 27 June 1836, when the county seat was formally relocated by Illinois law to Tremont, where a new court house had been built. Pekin then elected a new board on 8 Aug. 1836, the members of which were Samuel Pillsbury, Spencer Field, Jacob Eamon, John King, and David Mark. King was elected board president and Kellogg was again elected clerk.

On 18 Feb. 1837, the Illinois General Assembly approved the incorporation of the Pekin Hotel Company, whose members were Spencer Field, John W. Casey, Harlan Hatch, David Bailey, David Mark, Enos Coldren, and Gideon Rupert, who included some of the most prominent men in Pekin in those days. It is uncertain where these men established their hotel, but it seems likely it was within the first two blocks of the river.

Board members served one-year terms in those days, so Pekin held elections every year. Getting enough board members together for a quorum was evidently a real challenge. The board addressed that problem by passing of an ordinance on 4 Jan. 1838, stipulating that any board member who was more than 30 minutes late for a board meeting would forfeit $1 of his pay.

Another notable act of Pekin’s board around that time was a resolution of 29 Dec. 1840, adopting “an eagle of a quarter of a dollar of the new coinage” as the official seal of the town of Pekin.

Throughout these years, Pekin continued to see economic developments. The first bank in town, a branch of the Bank of Illinois, was established in 1839 or 1840 at the rear of a store on Second Street. There was not yet a bridge across the Illinois River, but ferries were licensed to operate. Alcohol distilleries also were established in the area that is still Pekin’s industrial district, and around those years Benjamin Kellog also built the first steam mill near the river between Margaret and Anna Eliza streets.

In spite of a scarlet fever epidemic in the winter of 1843-44, these economic developments were signs of Pekin’s continuing growth and progress, notwithstanding the loss of the county seat to Tremont. By the late 1840s, the pioneer town was poised to attain the status and rank of a City.