As Pekin has now entered its Bicentennial Year, it’s good to recall that 100 years ago the Pekin Daily Times included the words, “This is Pekin’s Centennial Year” in its front page masthead all throughout the year to remind its readers of upcoming Centennial celebrations.

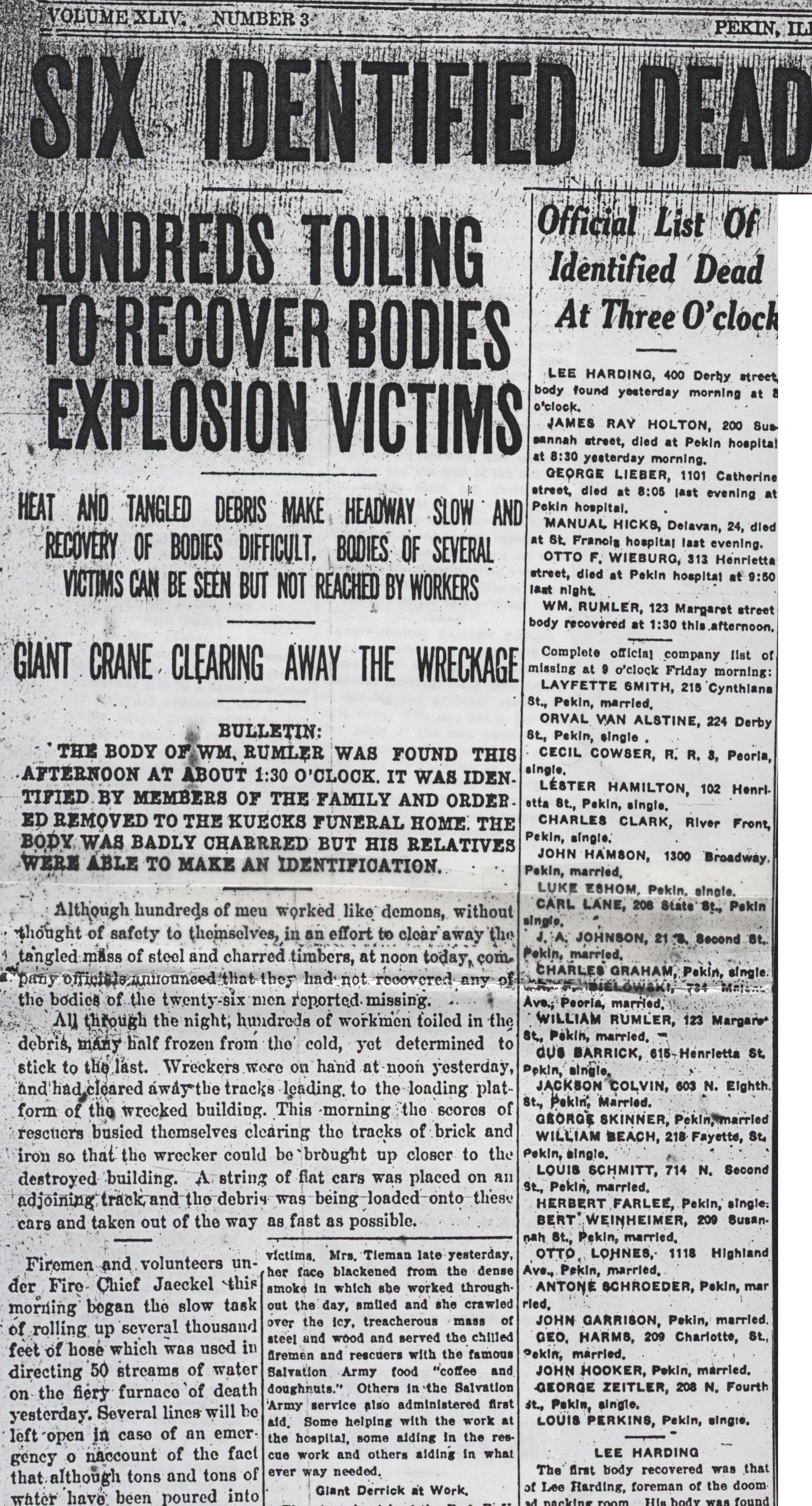

Yet in a kind of tragic irony, during the first weeks of January 1924, immediately beneath those words of anticipation and celebration the newspaper ran banner headlines and daily front page updates on rescue and recovery efforts at the site of the Corn Products Refining Company, that was hit by a horrific starch dust explosion and fire in the early morning hours of Thursday, 3 Jan. 1924. This was one of America’s worst industrial accidents up to that time, if not the worst, and the explosion shook Pekin both literally and emotionally and psychologically.

So, as Pekin commences its Bicentennial Year, the community has first paused to look back upon a significant but sad anniversary of a pivotal moment in its history. Yesterday, Wednesday, 3 Jan. 2024, a memorial program was held at the Pekin Moose Lodge to remember the Corn Products workers who died or were injured in the disaster, to honor their families, and to recognize the first responders, hospital staff, and community volunteers who united in response to the tragedy.

The program was organized by Alto Ingredients, the company that now owns and operates the former Corn Products plant and facilities, in cooperation with the Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society, the Pekin Fire Department, the Pekin Police Department, and United Steel, Paper and Forestry, Rubber, Manufacturing, Energy, Allied-Industrial and Service Workers International Union (USW).

In attendance at the half-hour program were about 95 people, including family members of some of the men who were killed in the explosion and fire. Pekin Fire Chief Trent Reeise and the Pekin Fire Department Honor Guard opened the program, and Bryon McGregor, president and CEO of Alto Ingredients offers words of welcome and acknowledgement of the workers’ descendants. Alto’s vice president of operations Todd Benton told the story of the disaster, the community’s response, and the industry safety improvements that were implemented in the aftermath.

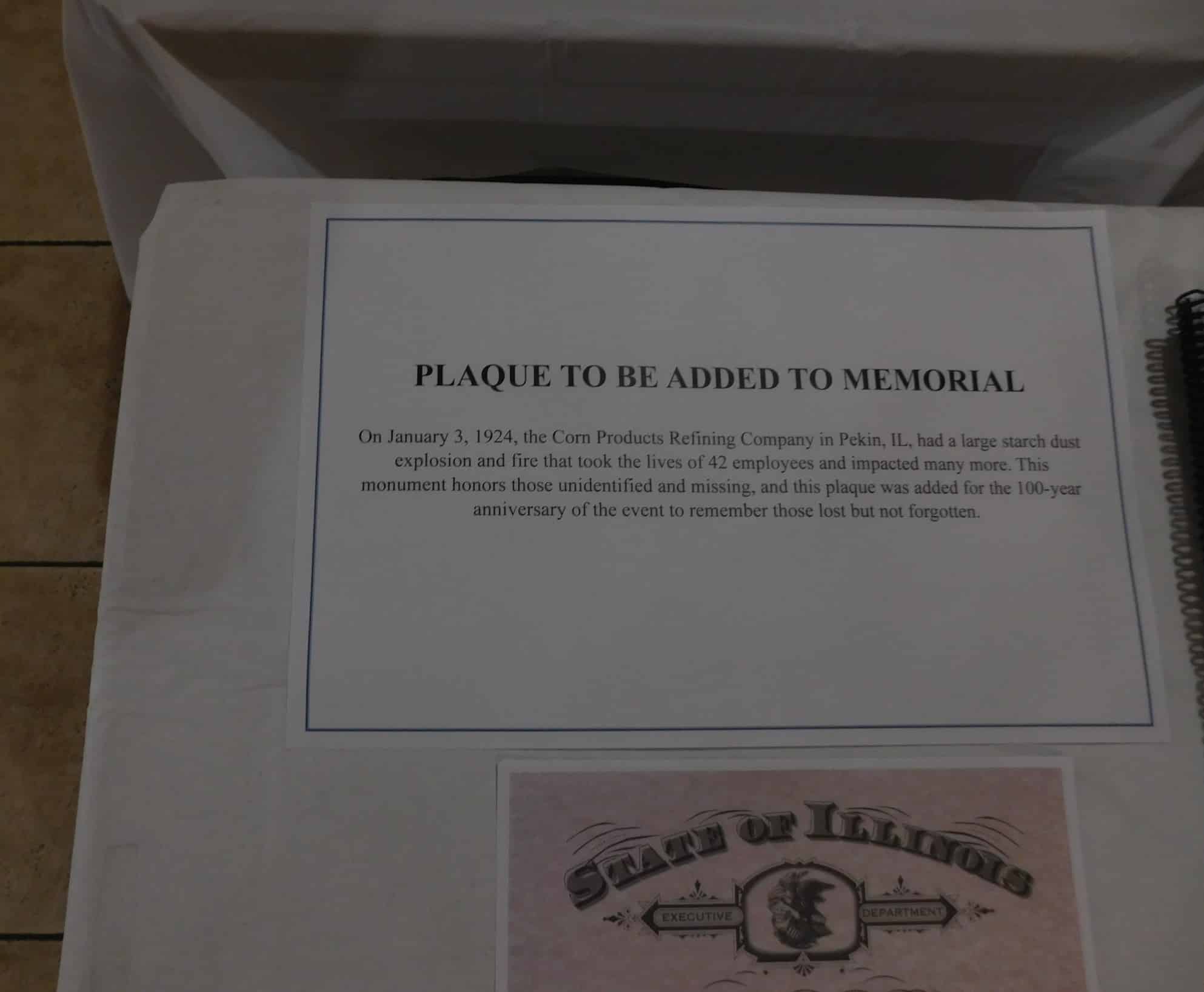

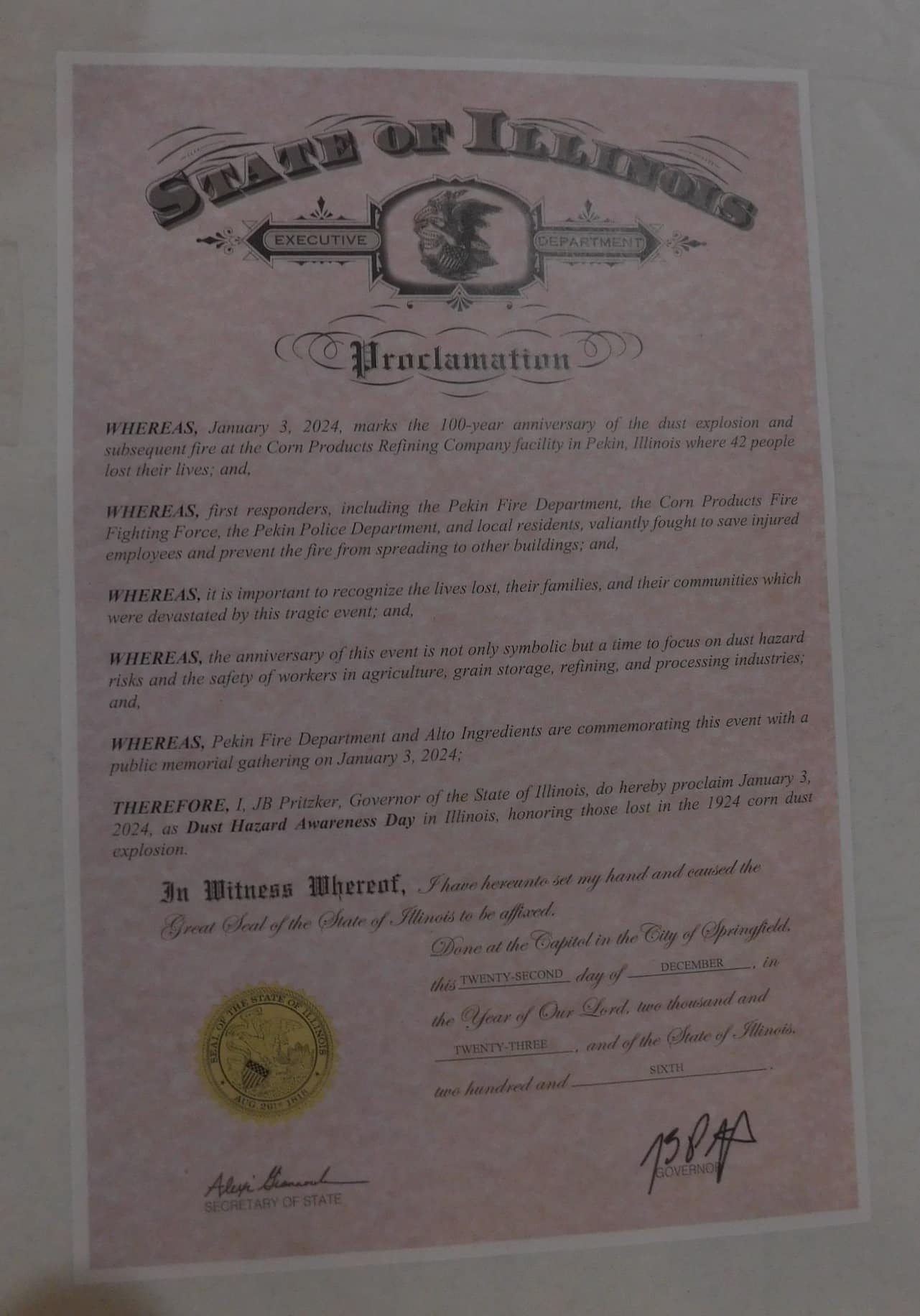

Following Benton was Alto’s vice president of quality and sustainability Stacy Swanson, who told of the Governor’s Proclamation of 3 Jan. 2024 as Dust Hazard Awareness Day, and showed the text of a new centennial plaque to be added this Spring to the Lakeside Cemetery monument to the missing and unidentified Corn Products victims. McGregor then offered closing thoughts and remarks.

Seed packets of forget-me-not flowers were distributed at the program in memory of all those affects by the 1924 Corn Products explosion. A fact sheet and map giving directions to the Lakeside Cemetery Corn Products monument was also passed out.

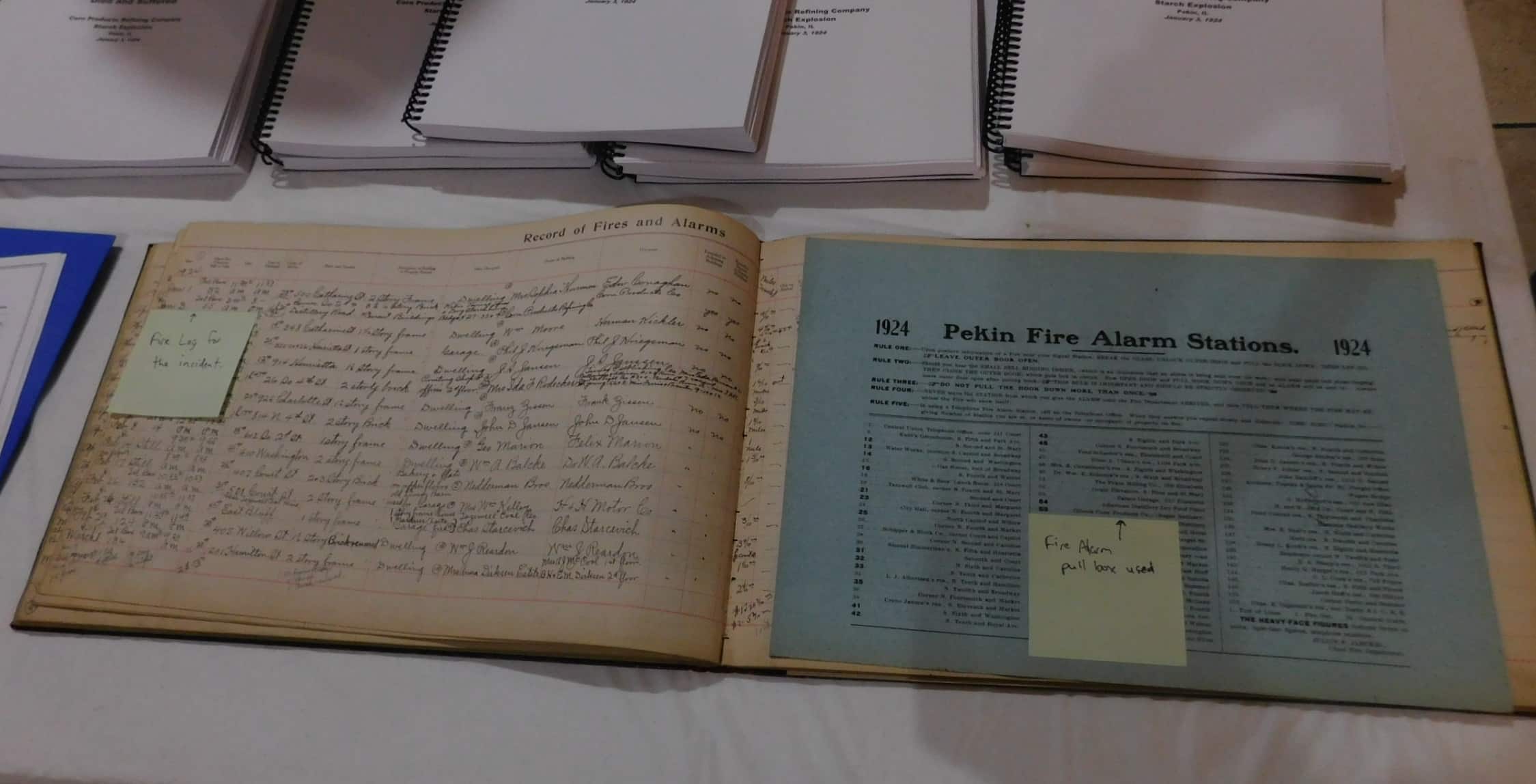

The Pekin Fire Department also displayed its January 1924 fire logs which included the Corn Products log entry. Fighting the fires of the Corn Products explosion was especially difficult and wearisome, with the early January temperatures dipping as low as -23 degrees Fahrenheit causing burst pipes, with the water freezing almost out of the fire hoses.

McGregor and Benton both brought attention to a new 91-page book on the tragedy, “1924-2024: Remembering Those Who Died and Suffered – Corn Products Refining Company Starch Explosion, Pekin, IL, January 3, 1924,” which was compiled and written in 2023 by Verna M. Hankins, a Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society, and sponsored by Stacy Swanson of Alto Ingredients. Hankin’s book is dedicated especially to the memory of the “men of 1924” who died or were injured in the disaster and to their families, but also tells the history of the Corn Products company, the first responders, the company officials, the investigators, and the community groups that banded together help the rescue and recovery efforts. A copy of Hankins’ book is available for study in the Pekin Public Library’s Local History Room collection.

Prior to the publication of Hankins’ book, information on the disaster was scattered here and there, and never before has this story been told at such length and breadth of detail. For example, the Pekin Centenary, page 61, being only a shorter volume giving an overview of Pekin’s history, devoted just a single sentence to the tragedy:

“The Corn Products Refining company plant was ripped by a series of dust explosions followed by roaring flames in 1924, and 42 workers died in the inferno while hundreds of others suffered burns and other injuries.”

Then, fifty years after the explosion and fire, the 1974 Pekin Sesquicentennial, pages 106-107, devoted nearly a full page to the story of the disaster, and later “Pekin: A Pictorial History” (1998, 2002) includes photographs. Following is the full text of the Sesquicentennial’s account of the Corn Products explosion:

“At about 3:30 a.m. January 3, 1924, third-shift workers at the Pekin Corn Products plant heard an explosion, immediately following which, observers reported, the starch-packing portion of the plant seemed to rise from its foundation. Then a giant tongue of flame shot into the air, a second explosion was heard, and the entire structure toppled, erupting into a living inferno for the men inside, many of whom were literally incinerated as the one million pounds of starch stored in the building started to burn. Later, victims found in the rubble of the building had to be identified by their brass identification checks, and in some cases, watches and teeth.

“The first-aid, personnel, and paymaster’s offices were in the immediate vicinity, and by the time Paymaster Charles Hough arrived (he had run all the way from his home to the plant, a distance of several blocks), victims lined the floors of the three offices. Immediately a bucket brigade was formed from the oil house (where plant-refined com oil was stored), and the buckets of oil were thrown on the sufferers in an action which was credited with saving many of their lives.

“As soon as the plant alarm whistle pinpointed the location of the explosion which many residents had already heard, the community responded. The Salvation Army was on hand almost at once, setting up a first-aid tent, aiding in rescue operations, and feeding rescuers and victims alike. Captain and Mrs. Tieman were in charge, and Mrs. Tieman seems to have been the ‘Florence Nightingale’ of the disaster, for nearly every newspaper account praises her tireless efforts in tending to the injured. Allegedly, the Pekin Ku Klux Klan was also on hand. Thirty-six of its members divided into three shifts to aid in the relief, providing food for the Salvation Army tent; trucks and drivers for transporting both men and materials; and aid to bereaved families in the form of food, fuel, and clothing.

“In the general confusion immediately after the explosion, many were reported missing or dead who had simply neglected to check out when they went home for the day, so a house-to-house check was initiated to establish precisely who needed to be accounted for. There was no central location to call for information, and soon the telephone company was swamped. Extra help was called in to handle the more than 50,000 calls in a 24-hour period (quite a strain for the equipment of that time, although today the switchboard routinely handles well over 133,000 calls daily).

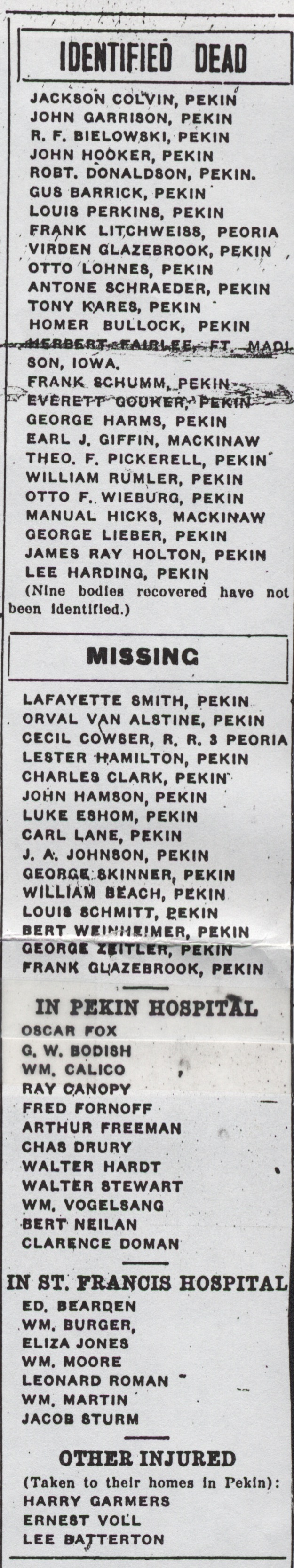

“The body of Otto Lohnes was the first to be recovered from the ruins of the starch-packing plant [sic – William J. Rumler’s body was the first, on Jan. 4, while Lohnes’ body was not recovered until Jan. 8, as Hankins shows]; the number of deceased pulled out after him, plus the number who died later in the hospitals (some had to be taken to Peoria) totaled 42. Twenty-two additional victims were maimed by injuries sustained in the tragedy. Of the number killed, ten were unidentifiable, and unsuccessful efforts to recover the last body led to the belief that it was cremated in the internal wreckage.

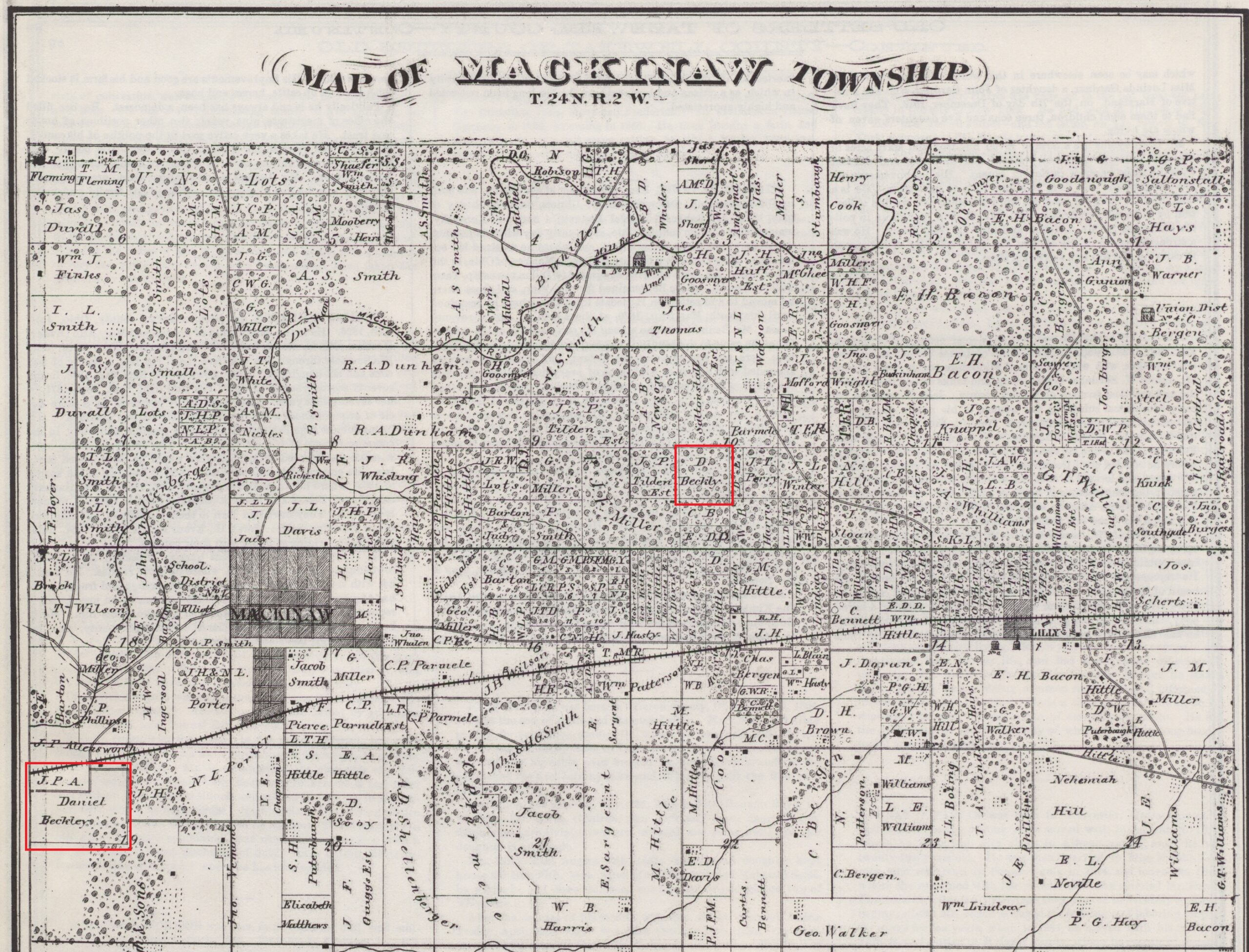

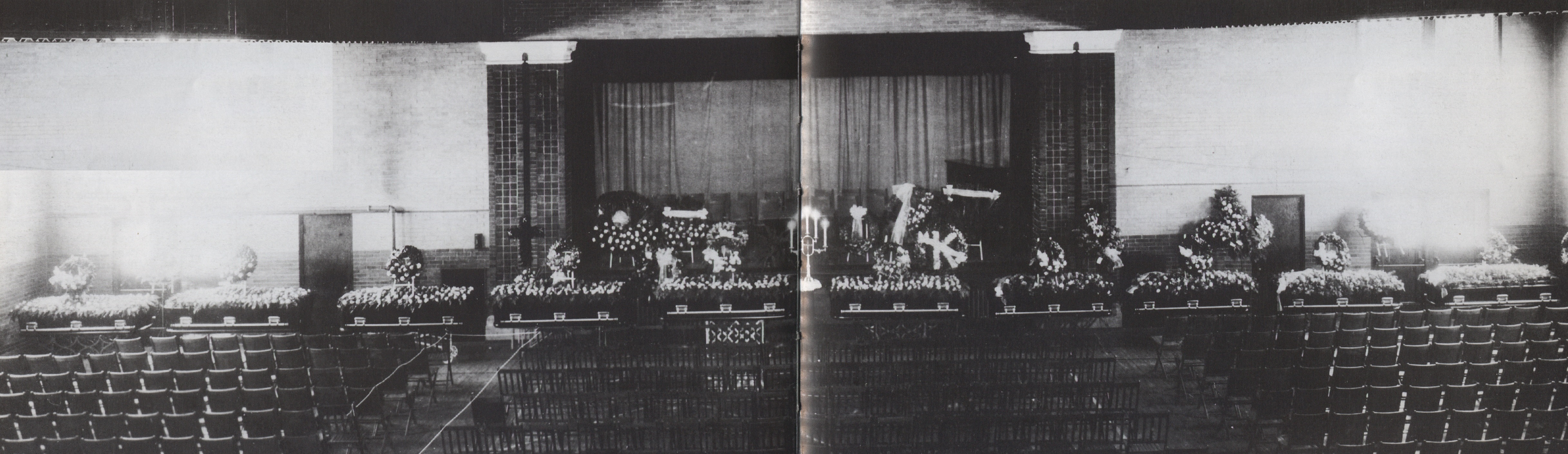

“Mass funerals were held on two successive days at the Pekin High School, the first for the identified dead, the second for the unidentifiable. A memorial plot for the ten unidentifiable and the one unrecovered body is located at Lakeside Cemetery.

“Ultimately, the state fire marshal and a government engineer decided that the explosion probably occurred when sparks from an overheated bearing in a conveyor box ignited starch dust on the floor of the building. The starch plant and an unused building connected to it were completely destroyed. A more substantial structure located nearby remained standing, but its windows were blown out and machinery torn loose. (Some several-hundred-pound kiln doors were blown as far as 30 feet.)

“The plant was closed down for about ten days until a temporary starch-packing unit could be constructed. This was replaced by a modern steel and concrete building in which all spills are carried back into the hopper by conveyor, and the walls are hosed down twice a day to prevent dust from accumulating.”

The Sesquicentennial’s reference to the KKK being among the community groups helping at the scene is addressed by Hankins on pages 47-48 of her book, in which she “painfully” acknowledges that the Klan was then ensconced in the community. (It presented itself then under the name of “The All-American Club”).

Among the many stories of heroism in the midst of this tragedy, the Local History Room collection includes a moving anecdote that was published in the 10 July 1924 issue of “The Companion for all the Family,” under that magazine’s “Angels” column. This anecdote is about Frank Lichtweiss (though it has some slight inaccuracies):

“HE SANG THEM TO SAFETY”

“A TERRIBLE explosion, a great burst of flame, shouts and groans of factory workers and then a clear young voice lifted in song! – a voice that quieted a group of injured men and guided them to safety.“It was midnight of January 2 when the explosion occurred that wrecked the Corn Products Company buildings of Pekin, Illinois. The buildings housed five hundred tons of corn starch and several thousand bushels of corn. In and about the factory were more than one hundred laborers. Without warning the buildings seemed to rise up, and men, machinery and materials were hurled through the air. Then everything seemed to catch fire at once.

“One large room on a third floor seemed to be the centre of the explosion. Every man there was injured, and escape from the fire seemed impossible; yet one of the workmen, Frank Leichtweiss (sic), the only son of Will Leichtweiss, the sheriff (sic – deputy sheriff), had the courage and the presence of mind to fight for his comrades. Frank has (sic) a wonderful voice, and when everything seemed lost because retreats and exits were cut off by the flames he began to sing.

“The workmen soon became quiet, and then as help came they were passed safely through the windows. Never for a moment did Frank cease his singing until all who were alive had been rescued.

“By that time, however, the fire had made such headway that, badly burned through he was, he was obliged to jump three stories to the crowd below. Bystanders gave him first aid and then rushed him, unconscious, to the hospital.

“When Frank’s father heard of the awful disaster and the injury to his son he hastened to the hospital with Frank’s wife, a bride of only a few days. The pair were almost frantic when they saw the unconscious form of the boy incased in great coatings of paraffin wax. The hardened sheriff was so unnerved that the nurses had forcibly to restrain him from taking his son’s broken body into his arms.

“’Don’t! Oh, don’t touch him, Mr. Leichtweiss!’ cried one of the nurses. ‘He sang his comrades from a fiery death!’

“’What’s that?’ demanded the sheriff.

“And as the nurse told the story Leichtweiss turned and, smiling while the tears streamed down his seamed cheeks, threw his shoulder back and cried: ‘That’s the kind of boy to have!’”

Hankins tells of Frank O. Lichtweiss on pages 124-125 and quotes several examples of the praise for his heroism. He succumbed to his injuries on 9 Jan. 1924.

This article was donated to the library on 4 April 1981 by Doris Rogers Holcomb of Ontario, California, whose uncle Earl J. Giffin was one of the Men of 1924. In her letter accompanying this “Companion” page, Holcomb said, “My Uncle, Earl Giffin, dead 1-5-1924 of lockjaw, refusing help in the hospital – ‘help those other poor s.o.b.’s, I’m alright.’ Which, of course, he was not.” Hankins tells of Earl Giffin on page 106 of her book, where she says Giffin’s cause of death was “a cerebral embolism and the injuries he sustained in the Corn Products explosion.”

Hankins chose as a thematic sentiment for her book a quote from Czeslaw Milosz in his book, “The Issa Valley”:

“The living owe it to those who no longer can speak to tell their story for them.”

Next week will present an overview of what the future site of Pekin and its environs were like in the period leading up to Jonathan Tharp’s arrival in 1824.