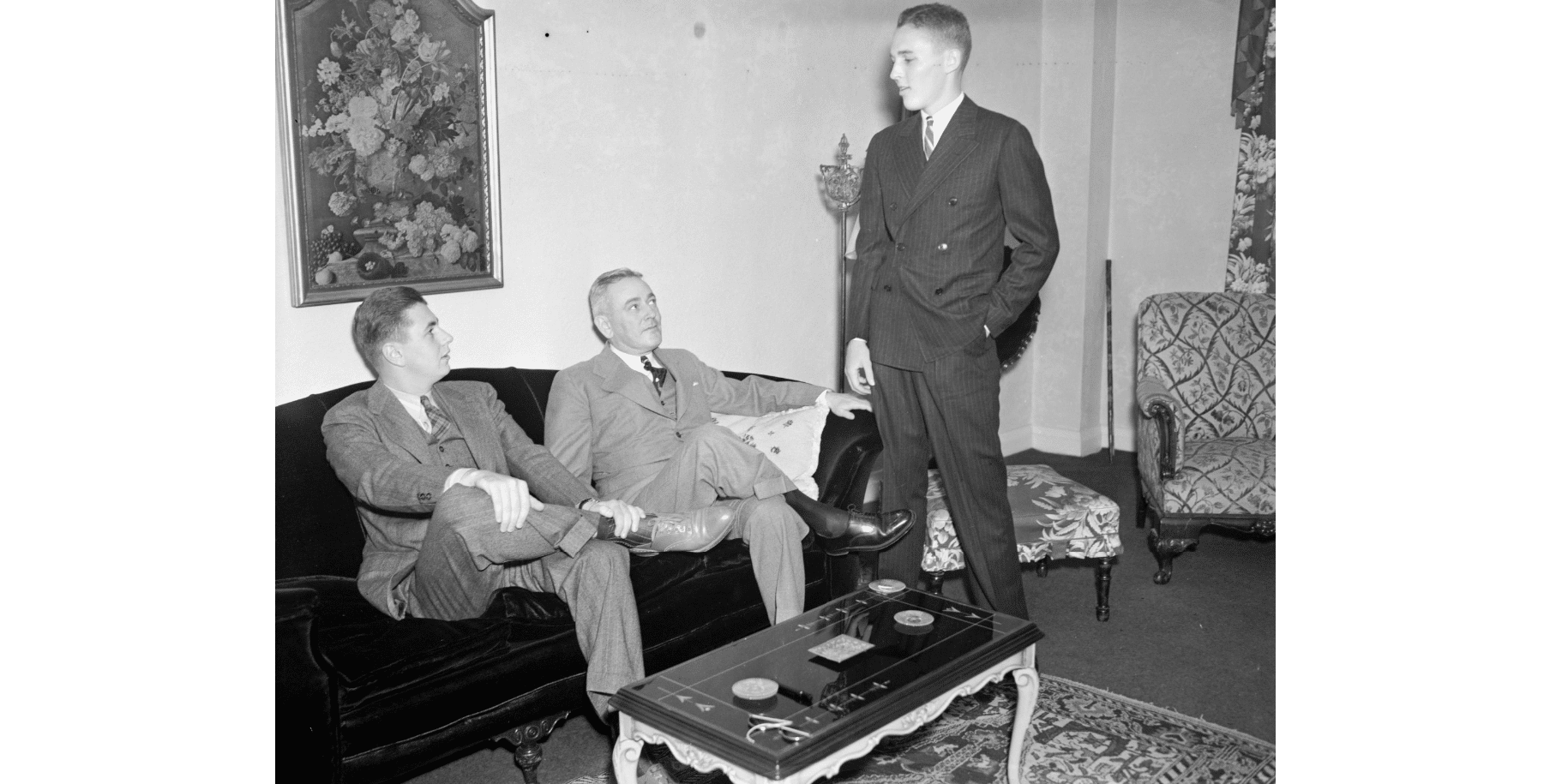

In last week’s installment of our series on the 1 March 1938 death of Betty E. Crabb of Delavan, we recalled the manslaughter trial of Betty’s husband James W. “Jimmie” Crabb II, scion of the wealthy Banking Crabbs of Delavan, who was accused of shooting Betty to death during a drunken rage.

Jimmie’s manslaughter trial ended on 11 June 1938 with a hung jury unable to decide whether Jimmie intentionally shot Betty or rather than Betty’s death was a tragic accident. The jury was certain, however, that Betty did not commit suicide as Jimmie originally had claimed.

Jimmie Crabb and his family and friends had to wait the much of the summer of 1938 to find out whether Tazewell County State’s Attorney Rayburn L. Russell and Special Prosecutor John E. Cassidy would attempt to retry Jimmie on manslaughter charges. Russell and Cassidy decided that a second manslaughter trial likely could end the same way as the first one, so instead chose to pursue the grand jury’s indictment of Jimmie for perjury.

The basis for Jimmie’s perjury indictment was fairly straightforward: while testifying under oath at the coroner’s inquest into his wife’s death, Jimmie made several claims that he later retracted when interrogated by Tazewell County Sheriff’s deputies, or which the death investigation had demonstrated could not possibly be true. Since Betty’s parents hoped Jimmie would be held responsible for her death, and the manslaughter jury had been unable to do that, the Collisons now pinned their hopes for even some modicum of justice on a perjury trial.

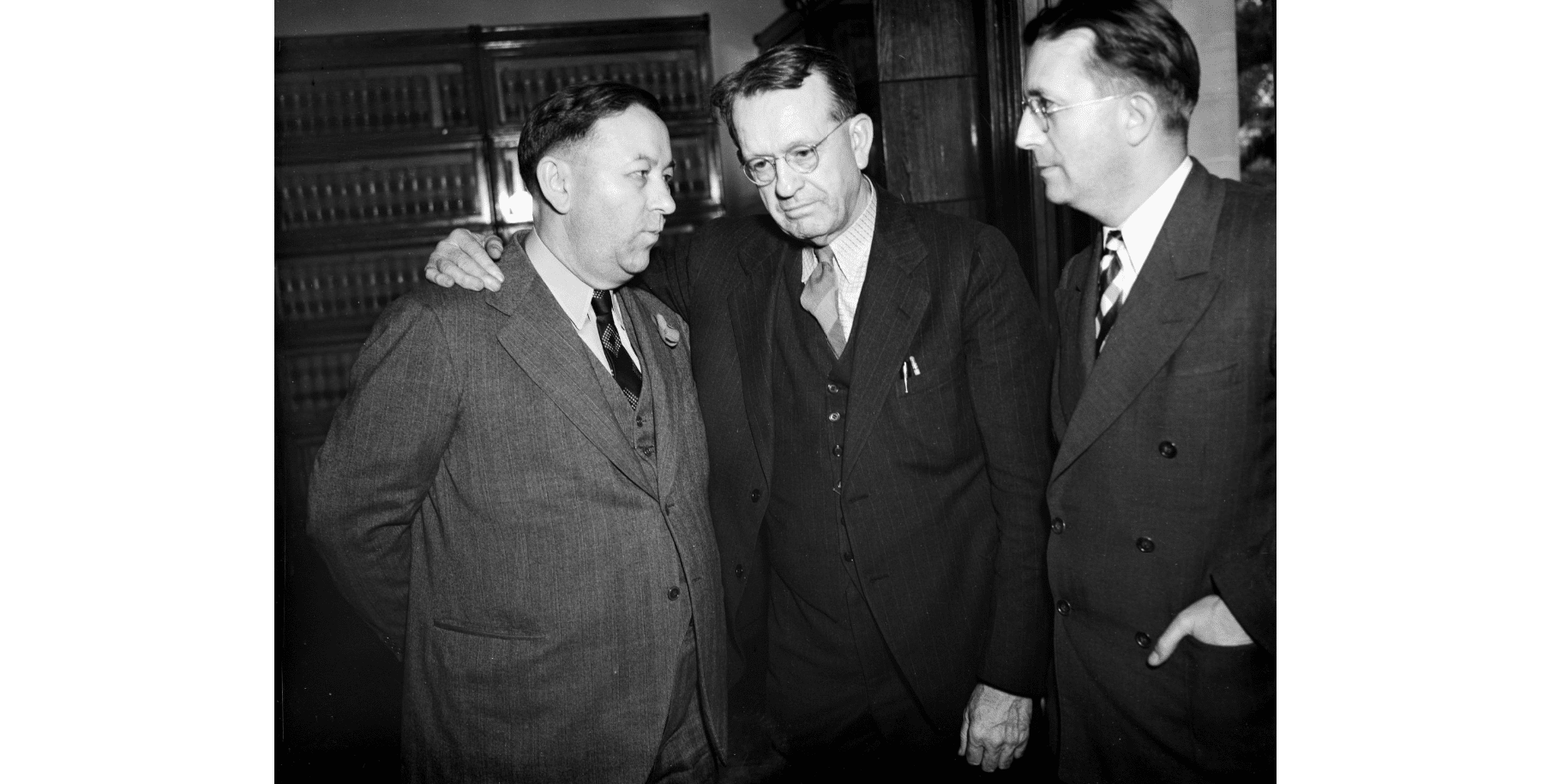

Jimmie Crabb’s perjury trial was nowhere near the undertaking that his manslaughter trial had been, and only lasted from 22 Sept. to 1 Oct. 1938. Once again representing The People were Special Prosecutor Cassidy and State’s Attorney Russell. Of Jimmie’s three defense attorneys in his manslaughter trial, only Judge William J. Reardon Sr. remained. Considering former State’s Attorney Louis P. Dunkelberg’s outrageous theft of the grand jury testimony during Jimmie’s trial, it is not surprising that he was not retained for the perjury trial.

As for J. M. Powers, he bowed out as attorney for the Crabbs because of a dispute with Jimmie’s father W. W. Crabb over payment of Jimmie’s legal bills. This was the first public indication that Jimmie’s legal troubles were having a serious impact on the Banking Crabbs finances. In place of Powers, W. W. Crabb hired Hal Stone, an attorney who was a real scrapper when defending his clients.

Instead of Judge Joseph E. Daily, his colleague Judge Henry Ingram was assigned to oversee Jimmie Crabb’s perjury trial. Another difference between the course of the perjury trial and the manslaughter trial is at the manslaughter trial Jimmie took the stand in his own defense. For his perjury trial, though, Jimmie did not testify in his own defense.

For all the witness testimony and evidence presented during the trial, the prosecution’s case depended on two crucial pieces of evidence. First, the State needed to have Jimmie Crabb’s sworn inquest testimony admitted as evidence, and secondly, the State needed the court to admit Jimmie’s unsigned statement taken at the Tazewell County Jail on 12 March 1938. The defense argued strenuously against the admission of the inquest testimony and the unsigned statement, but Judge Ingram ruled that both pieces of evidence could be admitted. With two contradictory statements presented to the jury for its consideration – one statement made under oath, and the other statement blatantly contradicting the sworn statement – the outlook was not good for Jimmie Crabb.

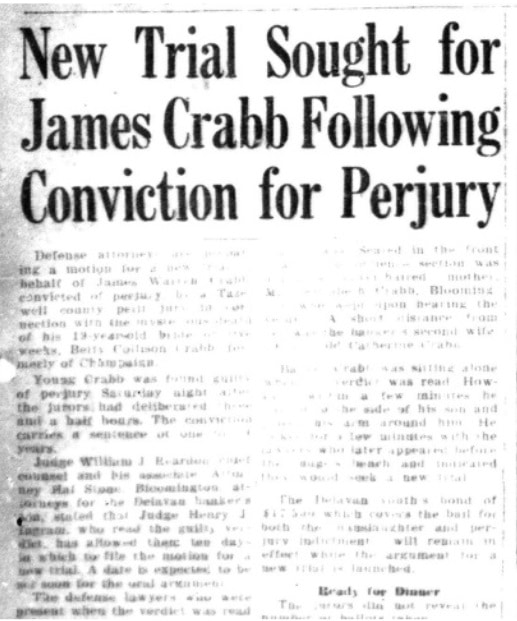

The jury took just three hours and 55 minutes to come back with a verdict of “guilty” at 6:35 p.m., Saturday, 1 Oct. 1938.

Nevertheless, James Warren Crabb II would never serve a day in prison for his perjury conviction. As soon as the jury handed in its verdict, Reardon and Stone moved for a new trial, with Stone arguing vociferously that Judge Ingram had committed a long list of some 20 trial errors. Understandably, Judge Ingram ruled against their motion (and Stone’s manner of argument did not likely endear him to Ingram either).

But the motion for a new trial is merely the first necessary step a defense attorney must make in order to appeal his client’s conviction. In this case, though, Reardon and Stone did not file a standard appeal and await the Illinois Appellate Court to make a decision on whether to hear the appeal and whether to overturn the conviction.

Instead, Reardon and Stone went straight to the Illinois Supreme Court and filed a Writ of Error asking the court to set aside Jimmie’s guilty verdict. The Illinois Supreme Court quite naturally declined to accept their request – for it is normal for the state Supreme Court to allow proceedings to unfold at a lower level rather than make an extraordinary act of intervention of this kind.

Undaunted, Reardon and Stone petitioned the Illinois Supreme Court for a rehearing to consider whether or not Jimmie’s conviction should be overturned – and this time, surprisingly, the court agreed to take the appeal!

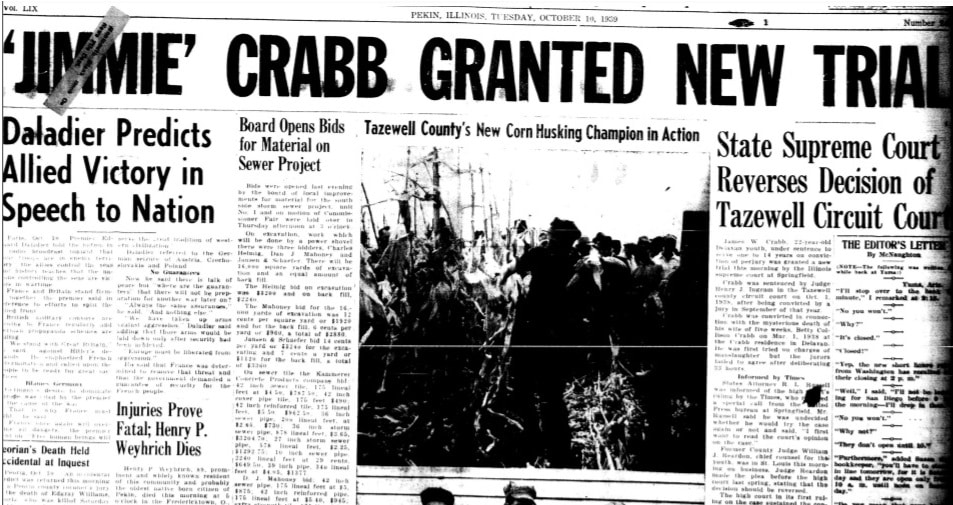

And so it came about on 10 Oct. 1939 – just over a year after being convicted of perjury – that Jimmie Crabb got the news that the Illinois Supreme Court had nullified his conviction. “It’s about time I was getting a break,” Jimmie said when reporters asked him about his successful appeal.

The court based their ruling on a narrow legal technicality, stating that when Sheriff Goar arrested Jimmie and read him his rights, warning him of his right to remain silent, Goar should have clearly explained that Jimmie’s words during the interrogation could not only be used in a murder or manslaughter trial, but also could make him liable for a perjury charge.

The Illinois Supreme Court’s standard by which they overturned Jimmie Crabb’s conviction is not, to my knowledge, the rule that must be followed by Illinois law enforcement agencies today, nor was it clear at the time of Jimmie’s arrest that it was the rule that Sheriff Goar should have followed. Be that as it may, Jimmie’s perjury conviction was now legally null and void, with his case remanded to Tazewell County for a possible retrial.

Once again State’s Attorney Russell had to decide whether or not to retry Jimmie Crabb – and this time, Russell decided that enough was enough. Two difficult and costly trials had failed to obtain any justice for Betty Crabb and her family.

Furthermore, by this time yet another shadow had fallen on the Crabb family. Next week we will conclude this series as we tell of the Fall of the House of Crabb.