This week’s installment of our series on the death of Betty Crabb and its aftermath tells of the grand jury’s indictment of Betty’s husband Jimmie Crabb and Jimmie’s criminal prosecution for his role in her death.

As we saw last week, the coroner’s inquest into the cause and manner of Betty Crabb’s death concluded on Saturday, 12 March 1938, with an open verdict – the inquest jury could not decide whether her death was an accident, a suicide, or a homicide, and asked for further investigation into how Betty came to be shot by her husband’s gun.

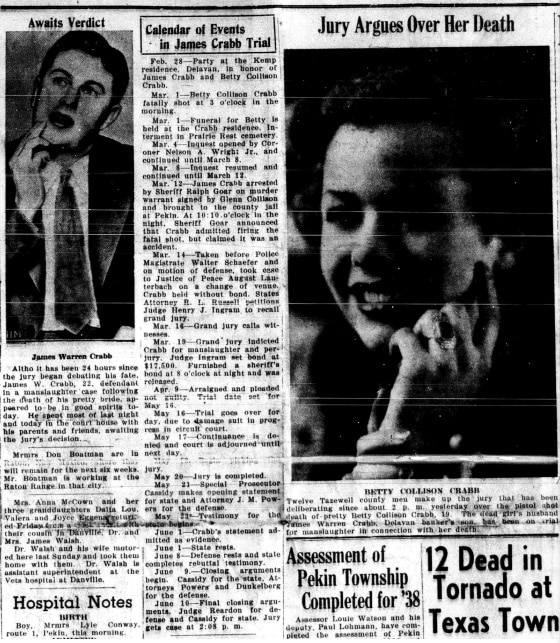

That same day, Tazewell County Sheriff Ralph C. Goar arrested Jimmie Crabb in a murder warrant after he finished his second round of inquest testimony in Delavan. Jimmie’s father-in-law Glenn Collison had sworn out the warrant for his arrest.

Jimmie was questioned at the Tazewell County Jail in Pekin, and that interrogation resulted in a witnessed written statement, released by Sheriff Goar at 10:10 p.m. Saturday, that included the shocking admission that Betty did not shoot herself as Jimmie had claimed. Changing his story, Jimmie now said that as he was holding and waving his Colt .45 pistol, Betty reached for the gun and was accidentally shot.

Jimmie refused to sign this statement, however.

Upon the release of Jimmie’s statement, reporters asked Sheriff Goar if it had been obtained from the use of “the third degree” – police torture. Goar bristled at the question and stated that no violence or harsh interrogation tactics had been used, nor did he tolerate any use of the third degree by his deputies. The “third degree” question was prompted by the sensational 1932 death of material witness Martin Virant, who was severely beaten and tortured by Sheriff’s deputies and died of his injuries in his jail cell, the deputies then attempting to fake a suicide by hanging to cover up the real cause of Virant’s death. Goar was Pekin police chief at the time, and provided important grand jury testimony against the accused deputies. Goar’s subsequent election as county sheriff was motivated in large part by citizens outraged by Virant’s death and the justice system’s failure to hold anyone responsible for it.

Following his arrest, Jimmie Crabb sat in jail over the weekend. He was arraigned before Justice of the Peace August Lauterbach on a charge of murder on Monday, 14 March 1938. The same day, Tazewell County State’s Attorney Rayburn L. Russell petitioned Tazewell County Circuit Court Judge Henry J. Ingram to recall the grand jury so it could consider the Crabb case.

The grand jury heard witnesses from 16 March to 19 March 1938, and concluded on 20 March with an indictment of James W. Crabb II on six counts of manslaughter. The grand jury also indicted Jimmie for perjury because his witnessed statement of 12 March flatly contradicted his sworn testimony at the coroner’s inquest.

State’s Attorney Russell saw that it would be make a difficult trial even more complicated to try Jimmie Crabb for both manslaughter and perjury in the same trial, so he decided to prosecute the manslaughter indictment first and leave the perjury indictment for a possible later trial.

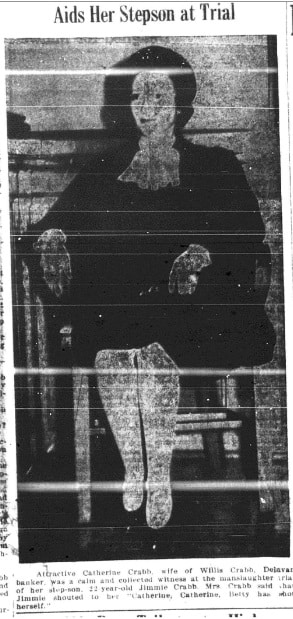

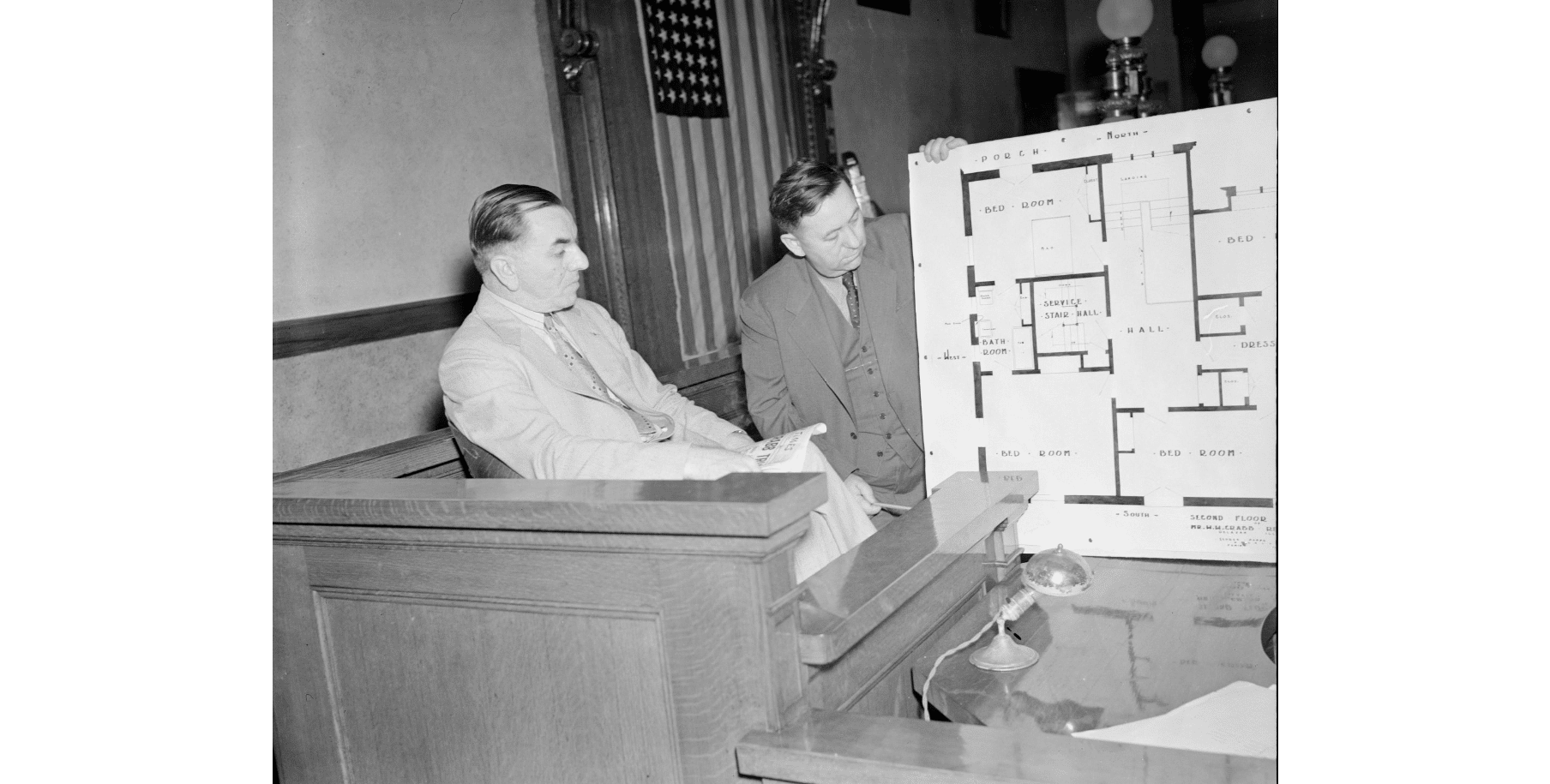

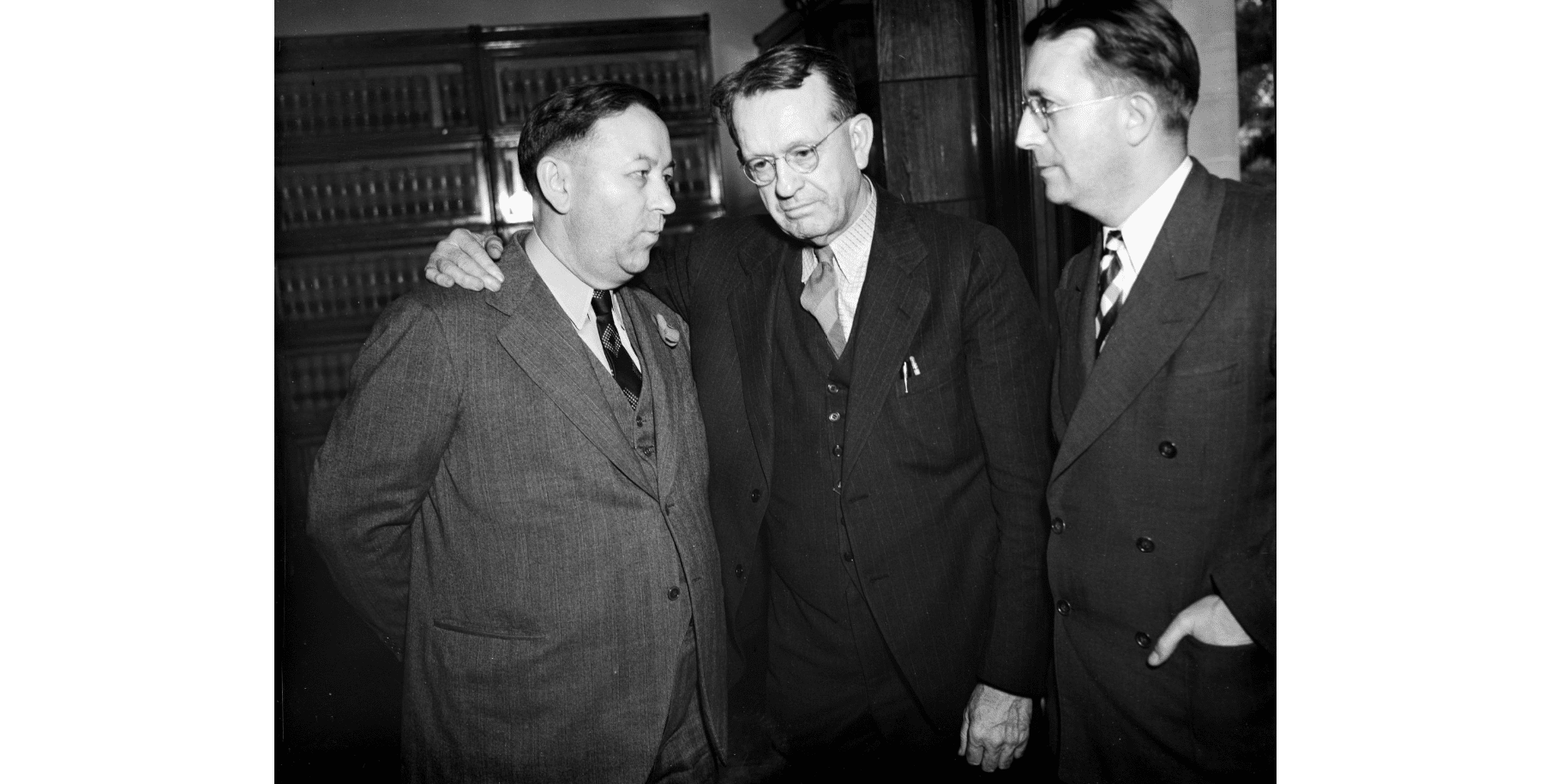

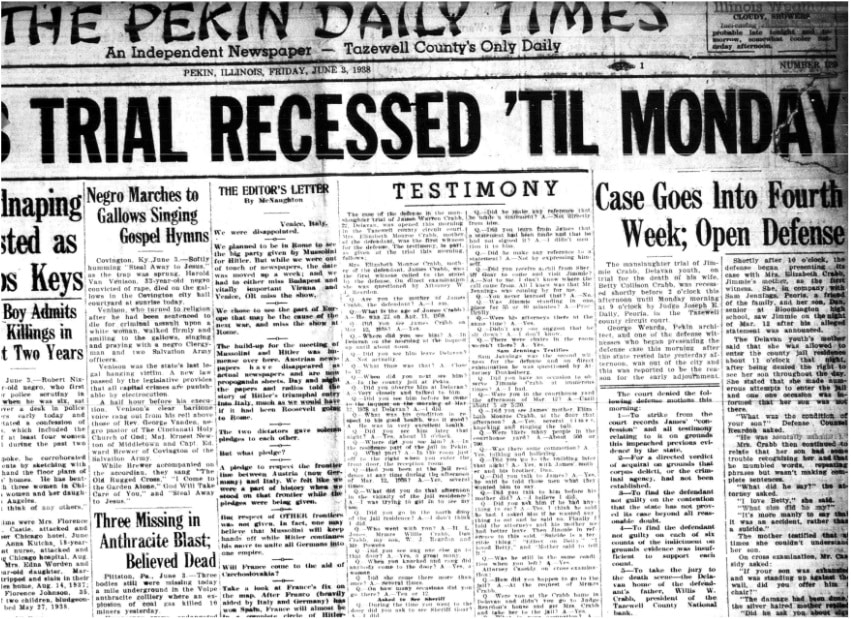

As Russell expected, the Crabb manslaughter trial turned out to be one of the biggest criminal trials in Tazewell County’s history, lasting from the empaneling of the jury on 17 May 1938 and concluding on 11 June 1938. The jury had to listen to and consider hours and hours of eyewitness, character, and expert testimony, as well as an array of technical evidence from the death scene. All the while, the local news media continued to cover this tragic story with great intensity. Newspaper photographers were even allowed in the courtroom, where they photographed the defendant and his family, witnesses, and even the jury – all of which photos were printed in the paper.

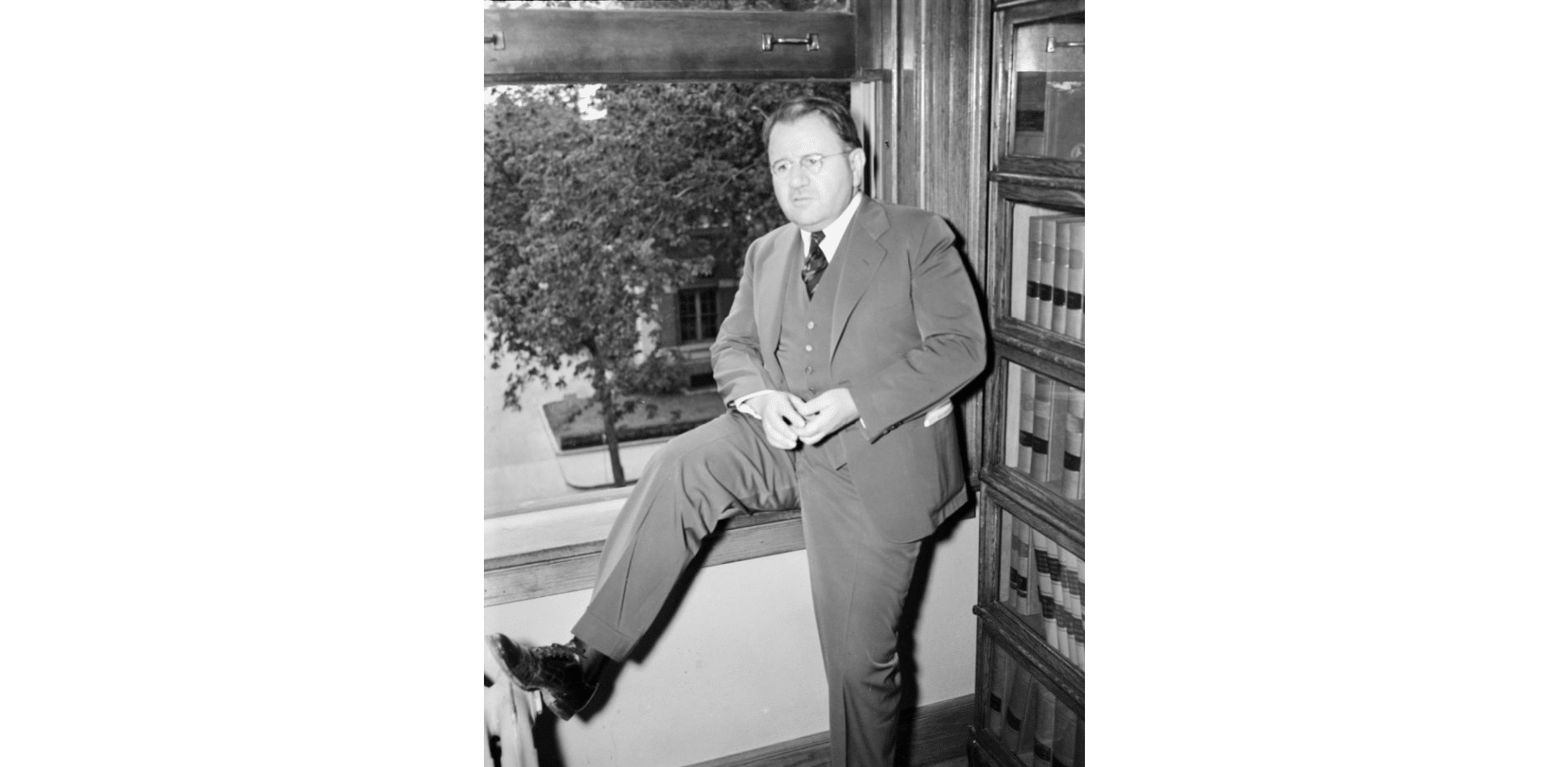

To assist him in the prosecution, Russell asked for and obtained the appointment of John E. Cassidy of Peoria as Special Prosecutor. (Immediately after this trial, Cassidy was appointed Illinois Attorney General.) As for Jimmie Crabb’s defense team, Judge William J. Reardon Sr. and J. M. Powers were joined by former Tazewell County State’s Attorney Louis P. Dunkelberg. Notably, Dunkelberg was the one who had charged the Tazewell County Sheriff’s deputies in the 1932 Martin Virant case, while Reardon and Jesse Black Jr. successfully defended the deputies. Reardon and Dunkelberg would now combine their lawyerly talents to try to keep Jimmie Crabb out of prison – and in his trial, Jimmie testified in his own defense.

The judge appointed for this trial was Joseph E. Daily, who had a reputation for being tough – and who also had been the judge for the 1932 Virant case. Reardon, Powers, and Dunkelberg would have preferred a different judge – though in the end it perhaps would have made no difference.

One may wonder whether Dunkelberg helped Crabb’s defense, though, in light of one of the crazier moments of this trial. At one point on 27 May 1938, after Cassidy had consulted his copy of the confidential grand jury record from Jimmie’s indictment, Dunkelberg asked if he could consult it as well. Cassidy handed him the record, whereupon Dunkelberg suddenly bolted out of the courtroom and managed to escape the courthouse, with Cassidy and Judge Daily hollering to the courtroom guards to stop him. Dunkelberg was found a few hours later at his residence, saying he had taken a drive out into the county to study the grand jury record at his leisure. When reporters asked Dunkelberg if he had learned anything that could help Jimmie Crabb’s defense, he only said, “I can’t really tell you, but it is nice to know what the other fella has.”

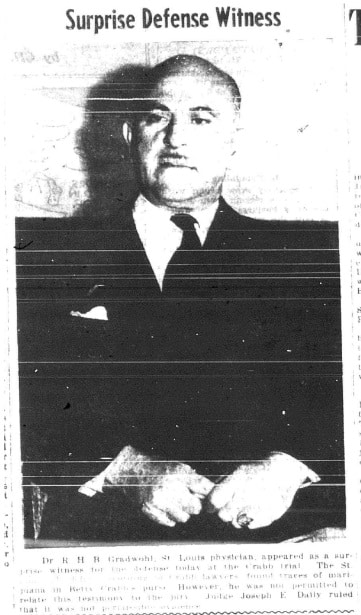

Another remarkable moment of the trial occurred just before Dunkelberg absconded with the grand jury testimony. In an effort to muddy the waters concerning Betty Crabb’s state of mind before her death, the defense team sought to introduce the expert testimony of Dr. R. H. B. Gradwohl of St. Louis, Mo., regarding a small amount of marijuana that had been found in Betty Crabb’s purse. However, Judge Daily disallowed Gradwohl’s testimony and the marijuana evidence because it was irrelevant.

Despite the best efforts of Cassidy and Russell, the weekslong trial ended with a hung jury that deliberated for 33 hours before Judge Daily dismissed the jurors. The jurors were sure Betty did not commit suicide, but simply could not agree on whether her shooting was an accident or an intentional act of Jimmie’s.

Now Russell and Cassidy had to decide whether or not to retry Jimmie Crabb for manslaughter. Next week we’ll find out what their decision was.