In recent years, the lives of Nance Legins-Costley (1813-1892) and her family have become much better known thanks chiefly to fresh light being brought to the subject as a result of the research of Carl Adams, who began delving into Nance’s story in the 1990s.

As we have related here at “From the History Room” more than once, Nance Legins-Costley is known to history as the first African-American slave to secure her freedom with the help of Abraham Lincoln. First appearing in published Pekin historical accounts in 1871 (in William H. Bates’ original narrative of Pekin’s early history), Nance and her persistent efforts to obtain acknowledgement of her freedom later were briefly mentioned in the 1949 Pekin Centenary volume. A much fuller (though far from complete) account was included in the 1974 Pekin Sesquicentennial (pp.6-7).

Apart from local historical narratives, prior to Adams’ research Nance’s story has been mostly relegated to relatively brief notices or passages in Lincoln biographies and studies. For example, John J. Duff devoted just four extended paragraphs to the story in his 1960 tome “A. Lincoln, Prairie Lawyer” (pp.86-87).

Adams himself has contributed two significant articles on the subject to the Abraham Lincoln Association’s newsletter, “For the People” – first, in the Autumn 1999 issue (vol. 1, no. 3), “The First Slave Freed by Abraham Lincoln: A Biographical Sketch of Nance Legins (Cox-Cromwell) Costley, circa 1813-1873,” and second, in the Fall 2015 issue (vol. 17, no. 3), “Countdown to Nance’s Emancipation.” Adams is also the author of the paper, “Lincoln’s First Freed Slave: A Review of Bailey v. Cromwell, 1841,” in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (vol. 101, nos. 3/4 – Fall-Winter 2008, pp.235-259). Finally, Adams has treated this subject in story form in his 2016 book, “NANCE: Trials of the First Slave Freed by Abraham Lincoln: A True Story of Mrs. Nance Legins-Costley.”

More recently, Nance and her story have been treated in a number of histories devoted to Lincoln or to the subject of American slavery.

For example, Lincoln scholar Guy C. Fraker addresses the case of Bailey v. Cromwell and McNaughton in a single paragraph on p.52 of his 2012 book, “Lincoln’s Ladder to the Presidency: The Eighth Judicial Circuit.” There Fraker offers a bit of polite criticism of the manner of telling the story of Nance and her trials “as a case where Lincoln’s role was to ‘free a slave,’” which Fraker says “is simply not accurate.” Rather, Fraker insists, “Nance’s gallant efforts to assert her free status, not Lincoln, resulted in her freedom.”

Fraker’s criticism is well received, because while Lincoln’s place in Nance’s story was very important in enabling her to secure the freedom that she always (and rightly) insisted was hers, this is in truth Nance’s life story rather than the story of how Lincoln purportedly set out to free a slave. From the standpoint of Lincoln scholarship, this case is significant as the first time Lincoln had to directly wrestle with the moral and legal issues related to slavery. But, as Adams himself agrees, from the viewpoint of Nance Legins-Costley this case was quite simply a matter of the greatest importance, because on it depended her freedom and that of her children.

Most recently, Lincoln historian and scholar Michael Burlingame tells the story of Nance and the case of Bailey v. Cromwell in a lengthy paragraph on pp.20-21 of his new (2021) book, “The Black Man’s President: Abraham Lincoln, African Americans, & the Pursuit of Racial Equality.”

As only to be expected in historians of the stature and scholarly diligence of Burlingame and Fraker, their accounts of Nance and Bailey v. Cromwell are accurate and informative.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to use those two adjectives to describe the way in which the story of Nance is told in M. Scott Heerman’s 2018 volume, “The Alchemy of Slavery: Human Bondage and Emancipation in the Illinois Country, 1730-1865.” I have not had occasion to give a close reading to Heerman’s entire book, which appears to be a generally compelling study of the manner in which human servitude was practiced in the officially free state of Illinois. Nevertheless, regarding Heerman’s treatment in his book of the life and trials of Nance Legins-Costley, a number of serious factual errors seem to have slipped past his fact checker during the editorial process.

Heerman introduces Nance and her trials in his chapter 4 (pp.105-106), where he refers to, “The first case, Nance, a Negro Girl v. John Howard (1828).” More accurately, that was the second case. The long tale of Nance’s struggles to win her freedom began (as Heerman himself describes) the previous year, when Nance’s master Thomas Cox’s possessions (including Nance and her family) were auctioned off to pay for a debt. She did not wait until 1828 to protest her freedom, but already in October of 1827 we find the freedom suit Nance, a Negro girl v. Nathan Cromwell. The second case, against Howard, was filed due to Sangamon County Coroner John Howard’s role in selling Nance to Cromwell.

Heerman returns to the story of Nance in his chapter 6 (pp.135-136), but here we again find factual errors. Of Nance he writes (p.135), “Born in Maryland around 1810, she was brought to Illinois and converted into a registered servant.” U.S. Census records consistently show Nance’s place of birth as Maryland, and indicate that she was born circa 1813. However, Adams’ research into Nance’s family history shows that she was born in Kaskaskia, Illinois, not Maryland. It was rather her master Nathan Cromwell who was born in Maryland, and presumably Nance, not knowing where she was born, herself came to believe she was born in Maryland as well. Her parents and siblings, who perhaps could have reminded her of where she was born, were sold away from her in 1827, when Nance was about 14. It was Nance’s parents Randol and Anachy (Ann) Legins, not Nance herself, who were brought to Illinois (by Nathaniel Green) – but they were from South Carolina, not Maryland.

Next, on the same page Heerman says, “In 1828, Nathan Cromwell sold Nance at public auction to John Howard. She disputed her sale before the Illinois Supreme Court, in Nance, a Negro girl v. John Howard (1828), . . . .” This is a remarkable instance of confusion on Heerman’s part. Howard did not purchase Nance; he rather oversaw the auction whereby Nance, an indentured servant of Thomas Cox, was sold to Nathan Cromwell. Heerman’s confusion seems to have arisen from his overlooking the earlier case of Nance v. Cromwell, and from misreading the court documents in Nance v. Howard.

Heerman once more returns to the story of Nance and her family in his concluding chapter (pp.166-167). There he correctly recalls that “In 1841, Abraham Lincoln helped to free Nance Cromwell from bondage in a local case, and during the war, her son William Costley took up arms.” But at this point we again encounter some very serious errors of fact.

Heerman proceeds to say that Nance’s son William “enlisted in the 26th Volunteers, and after fighting in Missouri and Mississippi, the company went to Virginia, where on April 9, 1865, Costley witnessed Lee’s formal surrender at Appomattox Courthouse.”

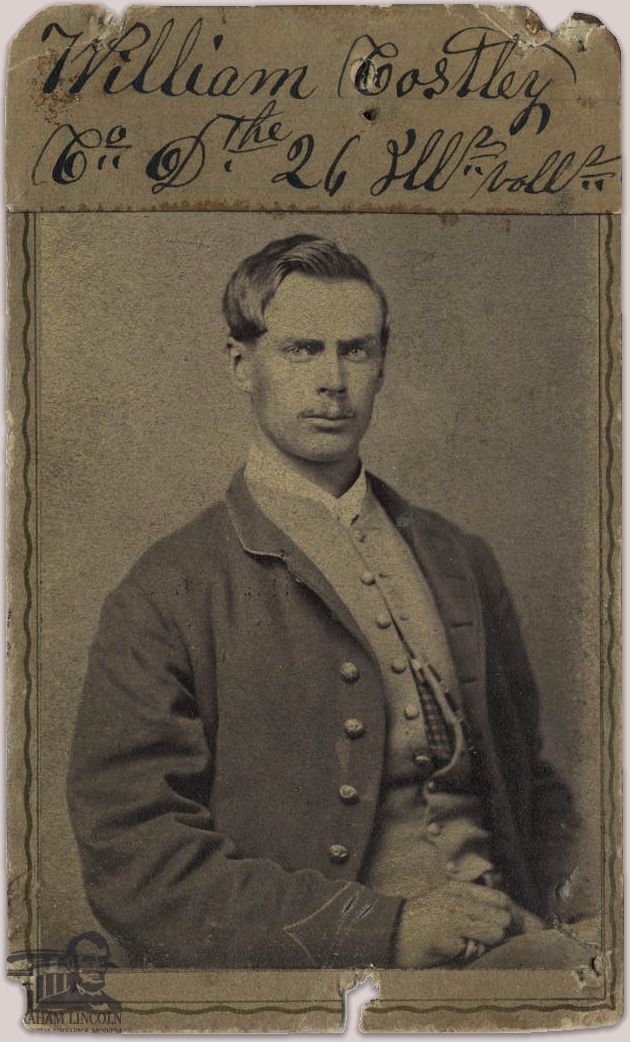

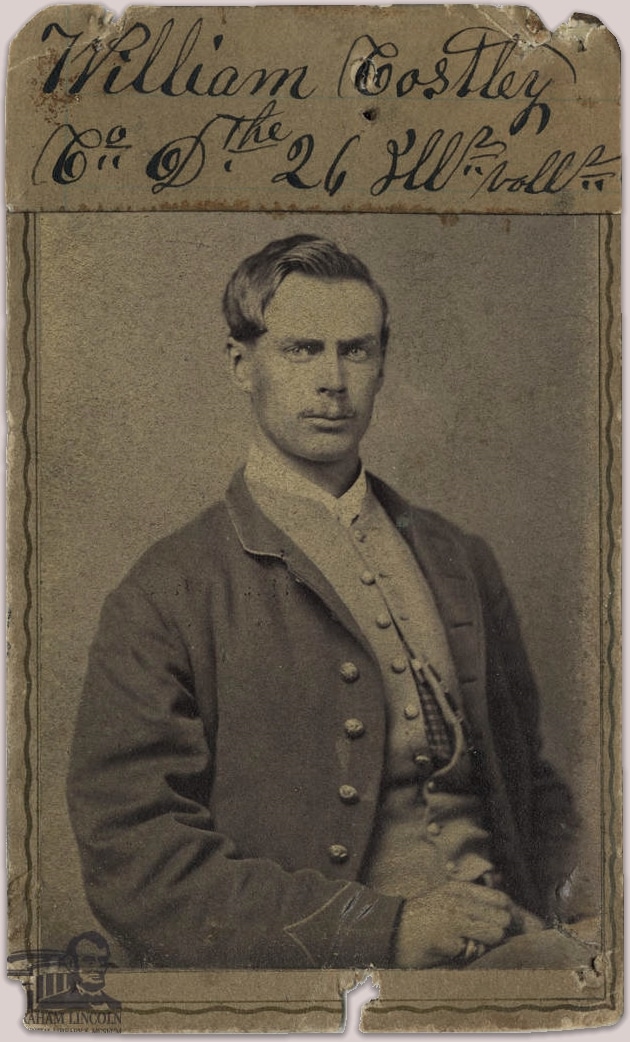

On this point, Heerman and his fact checker should have paused to consider how and why a black man, William Costley, would have served in a white Union regiment during the Civil War. Even more remarkable, on p.167 Heerman presents the photograph of a white Union soldier whose name, regiment, and company are written in cursive hand as “William Costley, Co. D, the 26 Ills Volls.” Heerman’s caption for this photo reads, “William Costley, son of Ben and Nancy Cromwell, age about twenty-one, Boys in Blue, Logan Collection, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, Springfield Ill.” (The same photo may be seen at William Costley’s Find-A-Grave memorial.) This same image appears on the front cover of Heerman’s book.

In fact, William Costley was the son of Ben and Nancy Costley, not Cromwell. “Cromwell” was one of the surnames that Nance bore during her lifetime – specifically, during the time she spent as a servant and ward of Nathan Cromwell. (Before that, she would have been known as Nance Legins and then Nance Cox, and the Peoria County marriage records of her children also give her a maiden name of “Allen”.) In this case, Heerman made a simple mental slip, for in his book he usually refers to Nance as “Nance Cromwell.”

However, he clearly has misidentified the white soldier William Henry Costley (1845-1903) of Weldon, DeWitt County, Illinois, as the black soldier William Henry Costley/Cosley (1840-1888) of Pekin, Tazewell County, Illinois. Nance’s son William (Bill) served in the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry, Co. B. – and although the 29th U.S.C.I. was present (along with the 26th Illinois Volunteers) at Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Bill himself was not there, because (as his pension file says) he was wounded in action on April 1 and subsequently was sent to a military hospital. Bill recovered in time, however, to take part in the landing at Galveston, Texas, on 18 June 1865, and thus was present for the first Juneteenth.

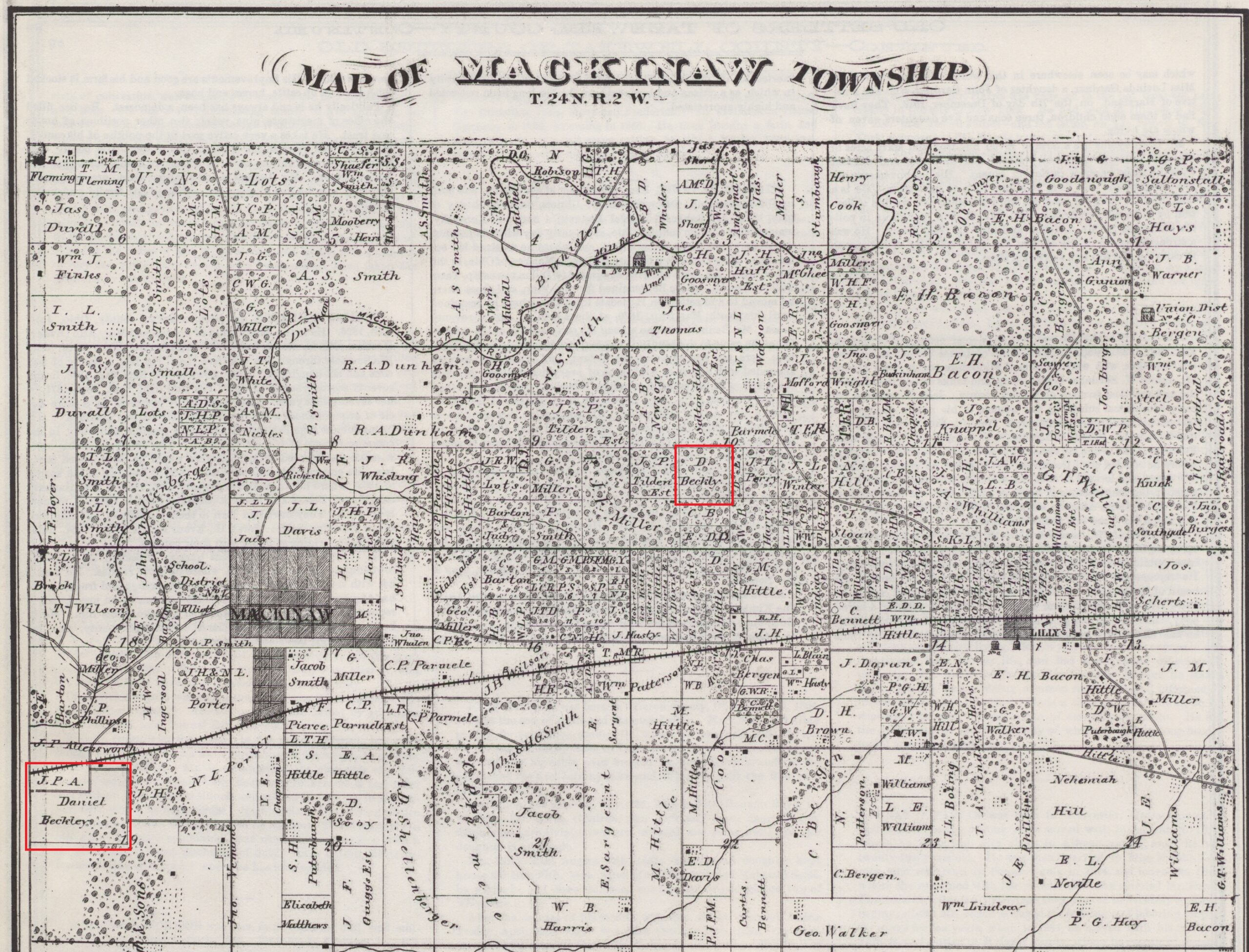

Incidentally, Carl Adams believes the white Costleys of DeWitt County may have formerly been the owners of Nance’s husband Benjamin Costley – a fascinating possibility that I have not been able to confirm or disprove. All we know at present is that Ben Costley was a free black, born in Illinois, and first appears on record in the 1840 U.S. Census as a head of household in Tazewell County, where he and Nance married on 15 Oct. 1840.

As I mentioned above, generally speaking Heerman’s work seems to make for a compelling study of the way slavery perdured in Illinois despite laws banning it — and he rightly and very helpfully places the story of Nance Legins-Costley in its broader historical context. However, Heerman’s fact errors and misinterpretation of primary documents regarding the story of Nance and her family (matters with which I have had occasion to become familiar), give us reason to be cautious and critical regarding his treatment of historical examples elsewhere in his book.