In September 2013 and January 2014, we recalled a dramatic story that was recorded in Charles C. Chapman’s “History of Tazewell County, Illinois” (1879) – the stirring account of the kidnapping of a family of free blacks from rural Tazewell County in 1827, and the bold and decisive actions taken by some of the county’s early settlers to rescue the victims.

The story, as Chapman recorded it, tells of how an early Tazewell County settler named Shipman had brought a family of free blacks with him to Illinois. The story in Chapman’s account does not name any of the blacks except the father, who is referred to simply as “Mose.”

The kidnappers struck in the middle of the night, seizing Mose and his family, but before the criminals had gone very far, Moses (who had a double row of sharp teeth) gnawed through his ropes and escaped, making his way back to the settlement and alerting his fellow pioneers. Johnson Sommers, William Woodrow, and Absalom Dillon mounted their horses and gave chase.

The pioneers rode hard in pursuit of the traffickers and managed to intercept them in St. Louis, Missouri, both pursuers and pursued landing on the Missouri side of the Mississippi River at the same time. Chapman’s account concludes:

“. . . Sommers jumped from his horse, gathered up a stone and swore he would crush the first one who attempted to leave the boat, and the men, who could steal the liberty of their fellow men, were passive before the stalwart pioneers.

“One of the pioneers hurried up to the city, and procured the arrest of the men. We do not know the penalty inflicted, but most likely it was nothing, or, at least, light, for in those days it was regarded as a legitimate business to traffic in human beings. The family was secured, however, and carried back to this county, where most of them lived and died. All honor to the daring humane pioneers.”

Quite frustratingly to local historical researchers, Chapman provides no other information on Mose and his family. He does not even tell us who “Shipman” was who had brought Mose and his family to Tazewell County. But subsequent research by members of the Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society was able to determine that “Shipman” was a Revolutionary War veteran from Kentucky named David Shipman (c.1760-1845) who is recorded as being buried in Antioch Cemetery near Tremont. Shipman’s probate file shows that the full name of “Mose” was “Moses Shipman,” who had adopted his former master’s surname, apparently out of gratitude for David Shipman’s having freed him and his wife and children. Moses and his family must have held David Shipman in great fondness, for when David died without any children, Moses handled the funeral arrangements and then purchased most of David’s possessions at the estate auction. The probate file includes reimbursement for Moses Shipman due to the diligent care he provided for David and David’s wife during their final years.

That still leaves numerous questions unanswered, though – namely, why did David Shipman come to Illinois, how and why did he free his slaves, and who were the other members of Moses Shipman’s family?

Census, marriage, and military records for the mid-19th century tell of several African-American Shipmans living in Tazewell and Peoria counties. No doubt they were related to Moses Shipman, very probably his children. One of them, as we mentioned a few weeks ago, was Pvt. Thomas G. L. Shipman, a Pekin native who served in the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry as a sharpshooter during the Civil War, giving his life for his country on 31 March 1865 and leaving a widow, Martha, and son, Franklin.

Another African-American Shipman was a woman named Mary Ann, whose son George W. Lee also served in the Colored Infantry during the war, afterwards marrying Mary Jane Costley, one of the children of Nance Legins-Costley of Pekin (but it is unknown if George and Mary Jane had any children, or least any who survived infancy).

While these records tell us a good deal about the African-American Shipmans of Tazewell and Peoria counties, they of themselves offer no confirming evidence that they were children of Moses Shipman, nor do they tell us who their mother was, or how and why David Shipman brought them to Tazewell County.

Research conducted by Susan Rynerson of the Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society has provided the answers to those questions, and then some.

The most important thing that Rynerson has discovered is that, contrary to the impression left by Chapman’s account, the family of Moses Shipman was not immediately brought back to Tazewell County. Rather, it took the intrepidity and endurance of Moses’ wife Milly, supported by the steadfast advocacy of Tazewell County’s abolitionist settlers, to convince Missouri’s courts that Milly Shipman, her children, and the others who had been kidnapped were free persons.

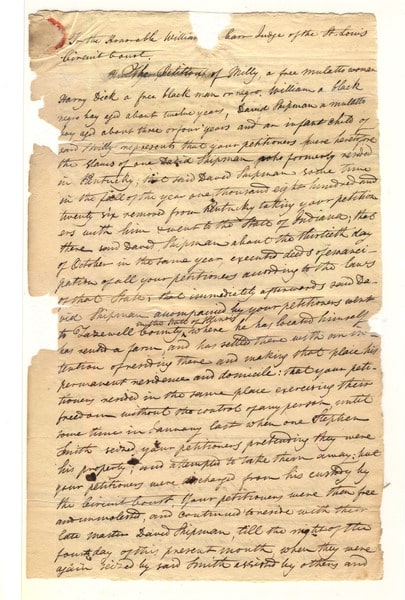

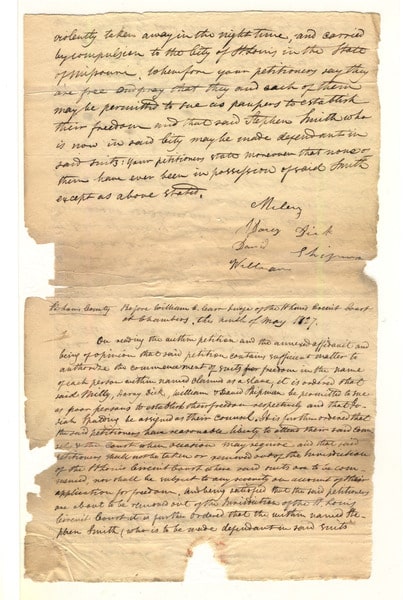

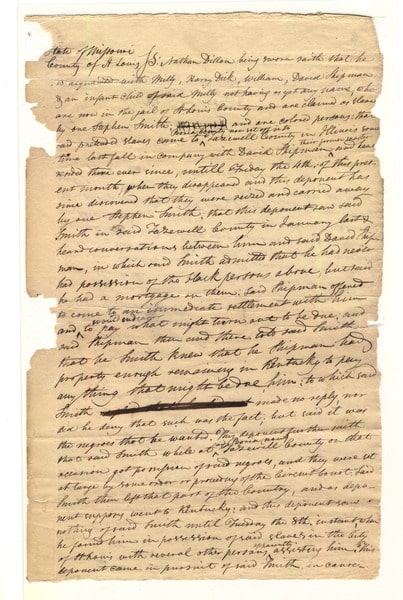

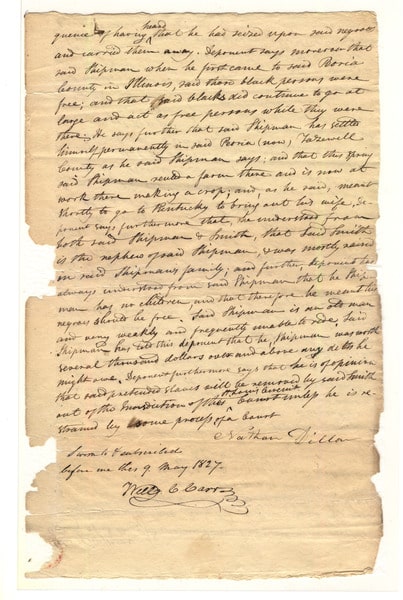

The full story of the ordeal of Milly Shipman and her children and companions can be learned by studying the 150 pages of the case file of Milly v. Stephen Smith (including papers from three related cases), which is available at the website of the library of Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. Milly’s 1827 case can be compared to the steadfast efforts of Nance Legins-Costley to secure recognition of her freedom, which at last was obtained through the 1841 case of Bailey v. Cromwell & McNaghton.

From those documents we learn that the kidnapping of the Shipman family was not a random attack of slavers looking for likely victims. It was more in the line of a family dispute involving a potential heir of David Shipman – namely, David’s nephew Stephen Smith of Kentucky, to whom David owed a sum of money. To help pay off that debt, two of David Shipman’s slaves in Shelby County, Kentucky, named Sarah, 27, and Eliza, 15, were seized and sold.

David, however, evidently wanted his slaves to be free, so he and his wife moved to Madison, Indiana, with the rest of his slaves. There on 3 Oct. 1826, David filed and recorded Deeds of Emancipation for the rest of his slaves, i.e., Moses, 30, Milly, 25, their children Allen, 4, Mary Ann, 3, and David, 15 months, and two others named Henry Dick, 16, and William, 12. David Shipman then moved to Tazewell County, Illinois, bringing his newly freed companions with him. (Mary Ann is certainly the Mary Ann Shipman Lee who was mother of Pvt. George W. Lee, while little David Shipman must be the David Shipman who married Elizabeth Ashby of the Fulton County African-American Ashbys.)

David Shipman’s actions were not at all to the liking of his nephew Stephen Smith, who had expected to inherit his uncle’s slaves and planned to sell them in order to obtain money to buy land. When he found out where his uncle had gone, he visited his uncle in Illinois and attempted to take the former slaves with him, but was prevented from doing so.

Smith then gathered a gang of kidnappers and on the night of 4 May 1827 – while everyone was asleep at his uncle’s home at what would later become Circleville in Tazewell County – seized the former slaves and dragged them down to the St. Louis slave market. Smith and his gang managed to grab Moses, Milly, little David, David’s infant brother (probably Charles), as well Henry Dick and William – but as we have seen, Moses escaped and made it back home, alerting his fellow settlers to what had happened.

The rescuing posse intercepted Smith and his gang with their victims on 8 May 1827. The posse members, including Nathan Dillon, quickly filed papers in St. Louis court to prevent Smith from carrying the kidnapping victims to any other jurisdiction. That gave Moses’ wife Milly and her companions time to file a freedom lawsuit that same month. (In one of the documents in the Milly v. Stephen Smith court file, Smith complains about what he saw as the meddling of David Shipman’s Quaker neighbors.)

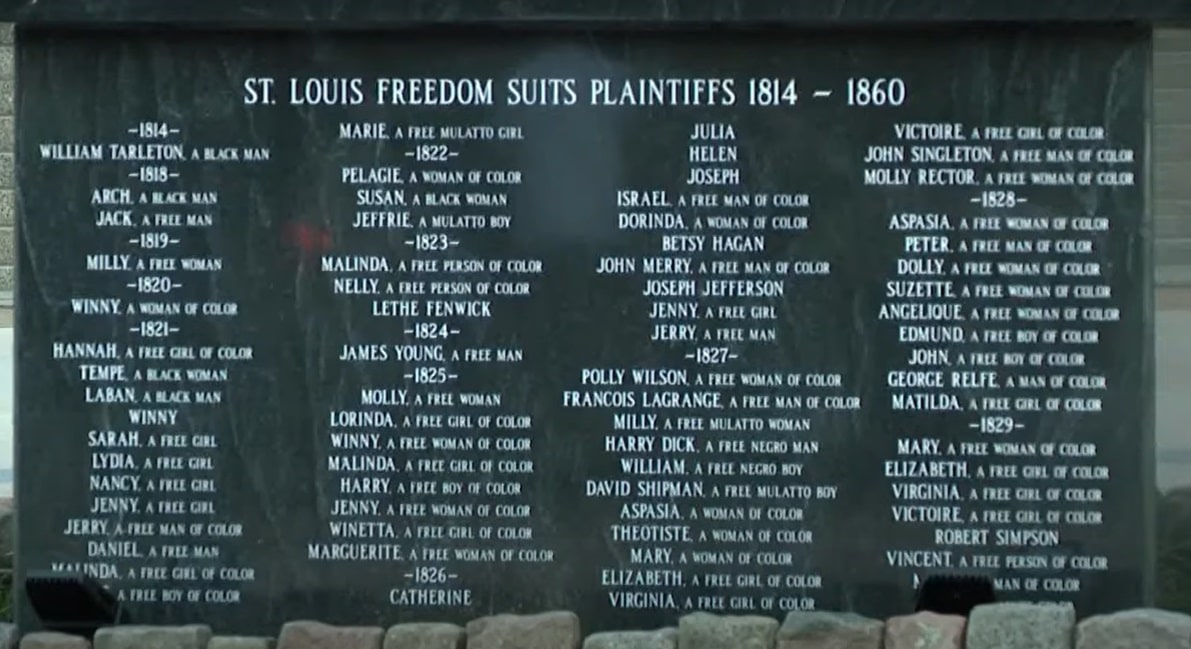

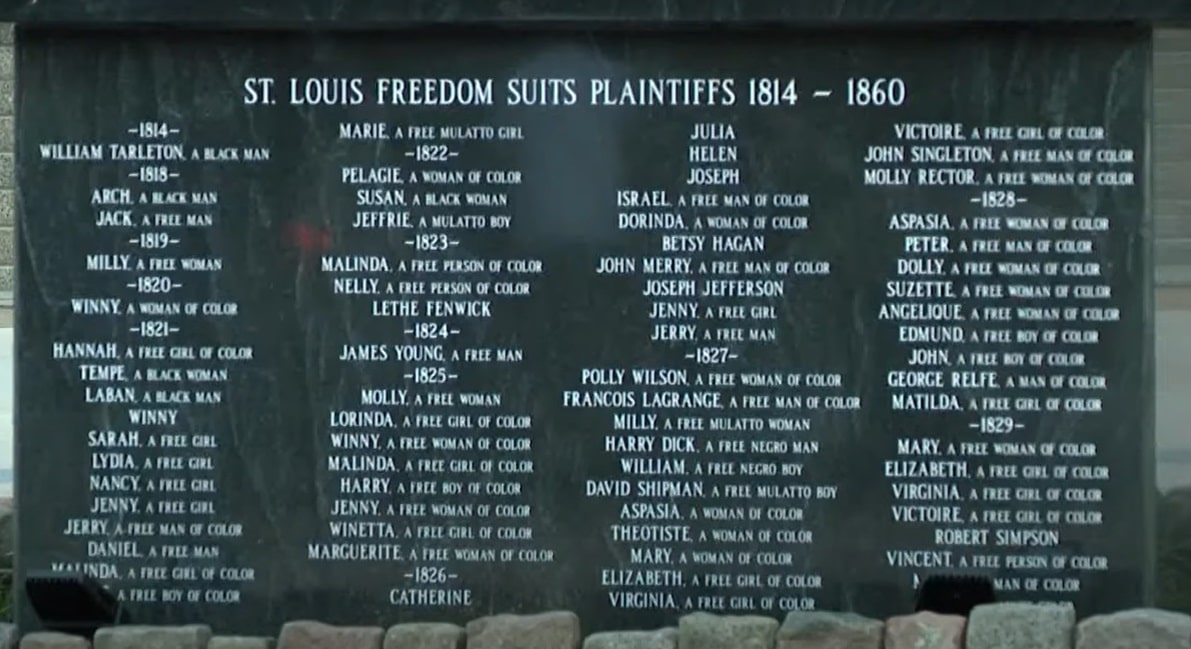

As historian Lea VanderVelde has related at length in her 2014 book “Redemption Songs: Suing for Freedom before Dred Scott,” Milly was one of numerous free blacks who petitioned for their freedom in Missouri during the 1800s under the legal rule then reigning in Missouri courts of “once free always free.” That is, even though Missouri was a slave state, their courts in those days did not allow the practice of kidnapping a free black in one state and selling him into slavery in Missouri. Just last month, on June 20 during Juneteenth weekend, a new memorial was unveiled outside the Civil Courts Building in St. Louis, inscribed with the names of every black person who brought a freedom suit in Missouri. Among the names on the memorial under the year 1827 are “Milly, a free mulatto woman,” “Harry Dick, a free negro man,” “William, a free negro boy,” and “David Shipman, a free mulatto boy.”

Milly and the others were held in St. Louis as her case slowly made its way through Missouri’s circuit court as depositions were taken from relevant witnesses in Kentucky and Illinois – with attorneys even traveling to the home of John L. Bogardus in Peoria to take deposition statements. The circuit court erroneously ruled in favor of Smith, claiming that David Shipman was not legally able to free his slaves on account of the money he owed his nephew. However, that judgment was overturned by the Missouri Supreme Court 23 Sept. 1829, finding that Shipman’s debt did not bar him from freeing his slaves. The case was then remanded to the circuit court, which confirmed the Supreme Court’s decision on 13 April 1830, and Smith was ordered to repay to Milly and her companions all court costs.

Milly and her children were at last able to reunite with Moses Shipman in Tazewell County. The 1840 U.S. Census shows David Shipman living in Tazewell County as the head of a household that included black persons whom Susan Rynerson has plausibly identified as Moses Shipman and wife Milly and their children Allen, Mary Ann, David, Charles, and Thomas, along with Henry Dick and William.

As I noted above, a few weeks ago we recalled the life of Thomas Shipman and his service in the Civil War. I am indebted to Susan Rynerson for bringing to my attention the fact that on the Tazewell County Veterans Memorial outside the courthouse, Thomas Shipman’s name is listed immediately below Milton S. Sommers, who was a son of Johnson Sommers, one of the men who pursued Stephen Smith to St. Louis and prevented Thomas’ mother and brothers from being sold back into slavery.