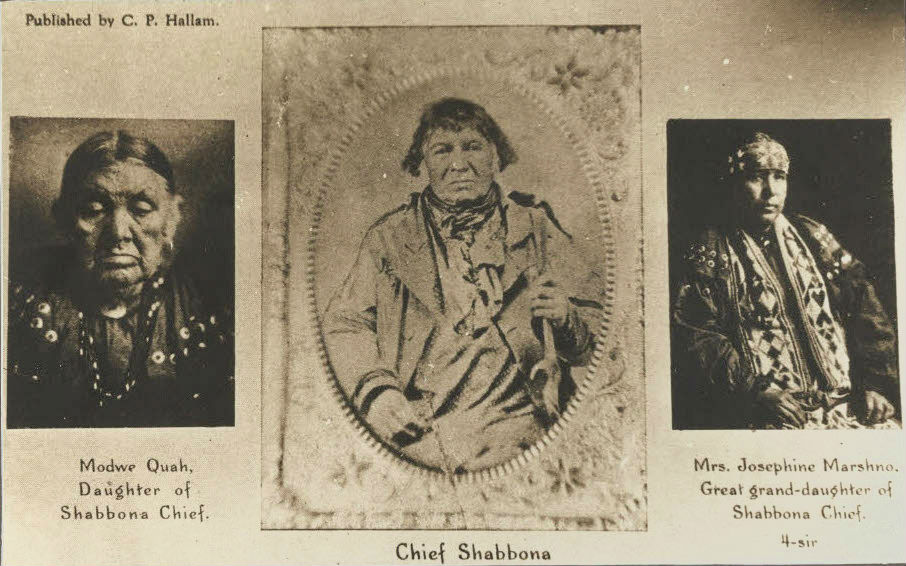

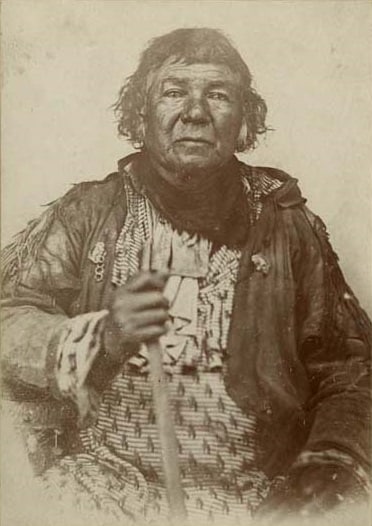

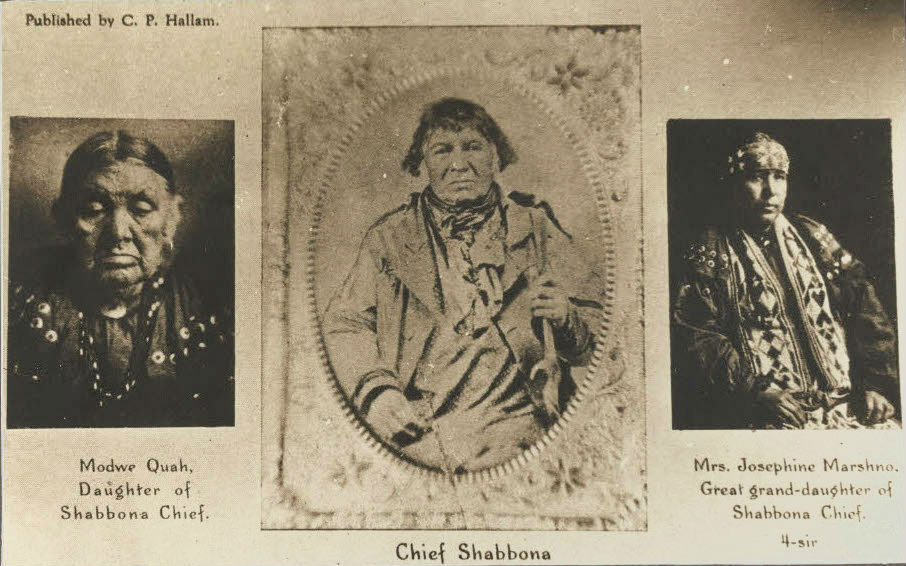

We have previously recalled the life of Pottawatomi leader Shabbona (c.1775-1859), who is mentioned in early Pekin historical accounts as briefly encamping with his family and a band of Pottawatomi at the site of Pekin circa 1830, pitching his wigwams just to the south of Jonathan Tharp’s cabin at the foot of Broadway.

As noted in an earlier “From the History Room” post, Shabbona (whose name is also spelled Shaubena and Shabonee, etc.) was prominent not only in the early history of Pekin and Tazewell County but also played a significant role in the wider history of Illinois, the Midwest and the U.S. At the time that Jonathan Tharp settled at the future site of Pekin in 1824, Shabbona’s camp was in the vicinity of Starved Rock, but Pekin pioneer historian William H. Bates indicates that around 1830 Shabbona and his family had set up a small village of Pottawatomi just south of Tharp’s cabin, between McLean Street and Broadway. But not much later, during the Black Hawk War of 1832 Shabbona and his family were camped in northern Illinois.

Though he fought against the U.S. alongside Tecumseh during the War of 1812, after Tecumeh’s defeat and death, Shabbona spent the rest of his life striving to remain at peace with his white neighbors, and during the Black Hawk War of 1832 he not only counseled the Pottawatomi not to support Black Hawk, but he aided the Illinois militia forces as a scout and on May 15 he and his son Pypegee and his nephew Pyps made a desperate early morning ride across northern Illinois to warn settlers on the prairie that Black Hawk’s war parties were on their way.

Shabbona’s ride is recounted by Nehemiah Matson in chapter 10 of his 1878 book “Memories of Shaubena,” based in part on Matson’s personal interviews of Shabbona. Matson writes,

“The first house Shaubena came to was squire Dimmick’s, who lived at Dimmick’s Grove, near the present site of La Moille. On notifying Dimmick of his danger, he in reply said, ‘he would stay until his corn was planted,’ saying, ‘he left the year before, and it proved a false alarm, and he believed it would be so this time.’ To this statement Shaubena replied, ‘If you will remain at home, send off your squaw and papooses, or they will be murdered before the rising of to-morrow’s sun!’ Shaubena had now mounted his pony, and on leaving, raised his hand high above his head, and in a loud voice exclaimed, ‘Auhaw Puckegee’ (You must leave!); and again his pony was on a gallop to notify others. Shaubena’s last remark caused Dimmick to change his mind, consequently he put his family into a wagon, and within one hour left his claim, never to return to it again.”

In this way, Shabbona saved the lives not only of the Dimmicks, but also the families of Chamberlin, Smith, Epperson, Moseley, Musgrave, Doolittle, and others. His brave and noble effort is the subject of a ballad written in 1927 by Thomas C. MacMillan of LaGrange, Illinois, entitled, “A Flag Creek Ballad: The Pottawatomies’ Last Camp and Shabbona’s Ride,” or “Shabbona’s Ride” for short.

“They told of brave Shabbona’s daring ride / When he warned the pioneers

Of Chief Black Hawk’s plans / With his hostile clans,

To ravage the wide frontiers.

“How he spurred by day, and sped in the dark. / On prairie, past treacherous swamp,

Where lurked the grim bear, / Near the fox’s lair,

And the ravening wolf-pack’s camp. . . .

“May the story of this bold soul survive / In the annals of our state,

Place Shabbona’s name / On its roll of fame

With the brave, and true, and great!”

As related at this weblog previously, after the Black Hawk War the State of Illinois resolved to clear the state of its remaining Native Americans – but for his friendship and help during the war, Shabbona and his family were granted a small reservation at Shabbona’s Grove. Even so, Shabbona at first wished to be with his people on their reservation in Western Kansas. That, however, was not to be, for the aid that Shabbona, Pypegee, and Pyps provided to white settlers in 1832 had made them enemies among other Indian tribes. As Matson relates:

“Shaubena’s band located on lands assigned them by the Government in Western Kansas, and here the old chief intended to end his days, but circumstances caused him to do otherwise. Soon after the band went West, the Sacs and Foxes were moved from Iowa to this country, and located in a village about fifty miles from Shaubena’s. Neopope, the principal chief of Black Hawk’s band, had frequently been heard to say that he would kill Shaubena, also his son and nephew, for notifying the settlers of their danger, and fighting against them in the late war. Shaubena had been warned of these threats, but he did not believe that Neopope would harm him.

“In the fall of 1837, Shaubena, with his two sons and nephew, accompanied by five others, went on a buffalo hunt about one hundred miles from home, where they expected to remain for some time. Neopope thinking this a good time to take his revenge, raised a war party and followed them. During the dead hour of the night, when all were asleep, this war party attacked the camp, killing Pypegee and Pyps, and wounding another hunter who was overtaken in his flight and slain. Shaubena, his son Smoke, with four other hunters, escaped from camp, but Neopope was on their trail and followed them almost to their home. After traveling over a hundred miles on foot without gun or blanket, and without tasting food, the fugitives reached home on the third day. Shaubena, knowing that he would be killed if he remained in Kansas, left it immediately, and with his family returned to his reservation in De Kalb county.”

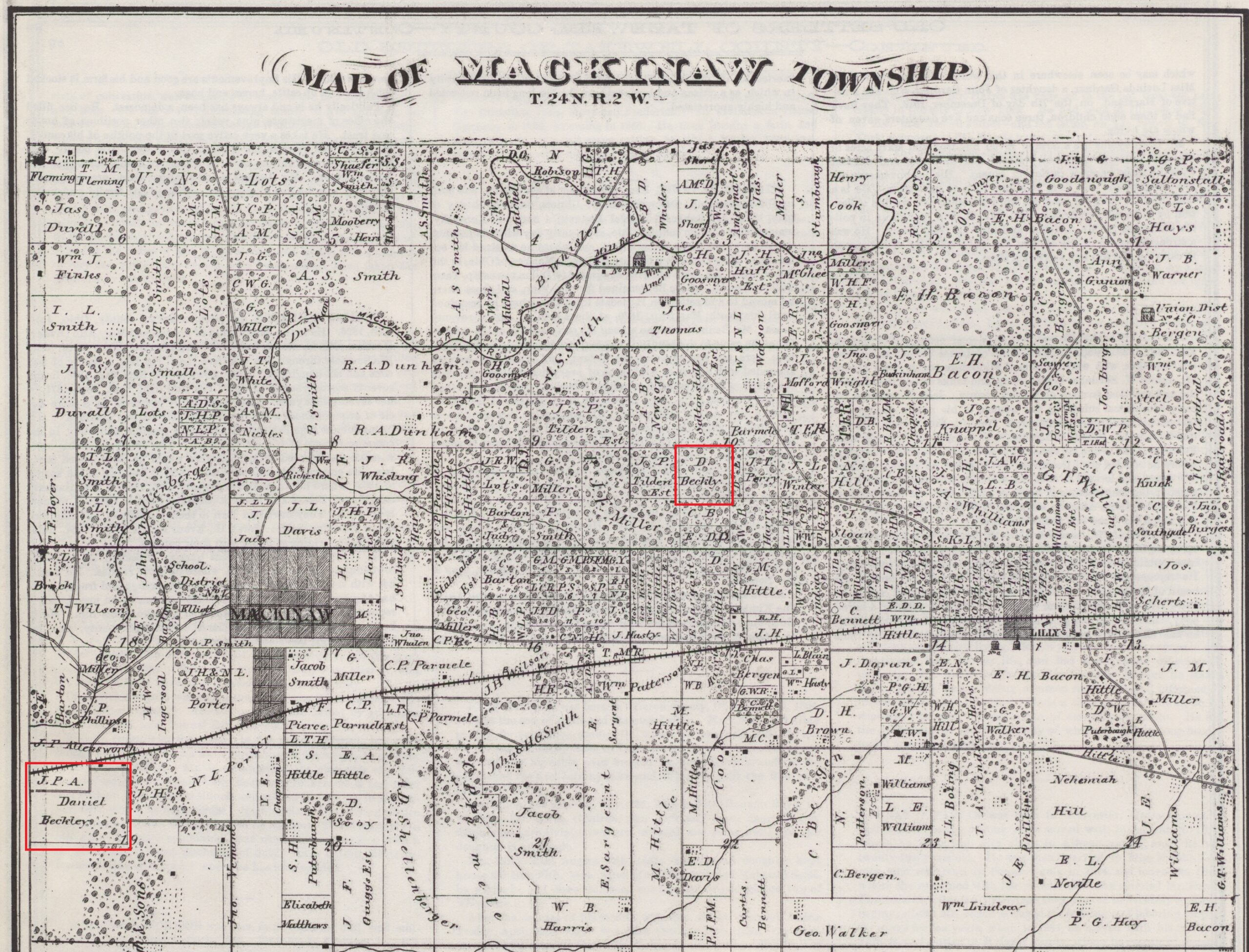

They remained on their Illinois reservation for the next 12 years. However, while visiting his kin in Western Kansas in 1849, his reservation was seized and declared forfeited. Upon his return in 1851, he found that he and his family were homeless.

George Armstrong of Morris, Illinois, former sheriff of Ottawa, promised him, “While I have a bed and home you shall share them with me.” The people of Ottawa then bought him some land on the south bank of the Illinois River about two miles upriver from Seneca, where he lived until his death on 17 July 1859.

Regarding the genealogy of Shabbona and his family, Matson says in the first chapter of his book:

“Shaubena, according to his statement, was born in the year 1775 or 1776, at an Indian village on the Kankakee river, now in Will county. His father was of the Ottawa tribe, and came from Michigan with Pontiac, about the year 1766, being one of the small band of followers who fled from the country after the defeat of that noted chief.”

Other sources state that Shabbona’s father Opawana was Chief Pontiac’s nephew. (Allan W. Eckert’s “A Sorrow in Our Heart: The Life of Tecumseh,” page 373, says Opawana fought beside Pontiac at the Siege of Detroit in 1763.) Continuing, Matson writes:

“Shaubena, in his youth, married a daughter of a Pottawatomie chief named Spotka, who had a village on the Illinois, a short distance above the mouth of Fox river. At the death of this chief, which occurred a few years afterwards, Shaubena succeeded him as head chief of the band.”

The number and identity of Shabbona’s wives is uncertain. Matson lists three wives: 1) an unnamed daughter of Spotka, 2) Mi-o-mex Ze-be-qua, and 3) Pok-a-no-ka. However, cemetery records and other sources show that Mi-o-mex was the same person as Pok-a-noka, while Shabbona’s last wife was a young Kickapoo named Nebebaquah (by whom Shabbona had a son named Obenesse; she died in 1878). In the court case “27 Ind. Cl. Comm. 187,” Sho-bon-ier (Shabbona?) is referred to as the son-in-law of Topenebe (or Topinabe), a Pottawatomi chief in Michigan near Chicago. Topinabe’s daughter was called Mimikwe – cf. Mi-o-mex. This would suggest that she would then be distinct from Shabbona’s unnamed first wife, daughter of Spotka.

Later in his book, in chapter 20, Matson provides the following account of Shabbona’s family:

“Shaubena, in his youth, married a daughter of a Pottawatomie chief, and by her he had two children. A few years afterward, this squaw and children died, and were buried at the grove; a pen of small timbers marked their resting place. In later years, Shaubena was in the habit of taking visitors to the graveyard and pointing out the graves of loved ones, while tears would trickle down his tawny cheeks.

“After the death of his first squaw, Shaubena married another, named Mi-o-mex Ze-be-qua, and by her he had a number of children. In accordance with Indian customs, some years afterward he married another squaw, and for a time lived with both of them. The latter was a young squaw of great personal attractions, named Pok-a-no-ka, and by her he had a large family of children. The old and young squaw did not live together in perfect harmony, and their quarrels would sometimes lead to open hostility. On account of these disagreements, Pok-a-no-ka in later years left the family and lived with her people in Kansas.

“The oldest son of Shaubena, whose Indian name was Pypegee, but known everywhere among the early settlers as Bill Shaubena, was a fine intelligent youth, spoke English quite well, and, like his father, frequently visited the cabins of settlers. He tried to court a daughter of one of the early settlers, and it appeared to have been the height of his ambition (as he expressed it) to marry a white squaw. In the fall of 1837, Pypegee was killed, in Kansas, by a party of Sacs and Foxes, on account of his fidelity to the whites, as previously stated.

“Shaubena’s second son, named Smoke, possessed a fine commanding figure, very handsome, and a great favorite among the whites. In 1847, Smoke, while returning from Kansas, where he had been on a visit, was taken sick in Iowa and died among the whites, and by them received a Christian burial.

“The youngest son, Ma-mas, became dissipated, and is now living with his band in Kansas.

“Shaubena had many daughters, two of whom were young and unmarried at the time of his death. One of his daughters married a Frenchman named Beaubien, who lived near Chicago, but Ze-be-qua was his beautiful daughter who at one time was the belle of the settlement.

“Shaubena’s family, while at the grove, consisted of twenty-five or thirty persons, including his two squaws, children, grandchildren, nephews, nieces, etc. He would frequently take the little ones to church with him on the Sabbath day, and take much pains to keep them quiet during the service.

“While at the grove, Shaubena had a niece living with him, a young squaw of about fifteen years of age and of prepossessing appearance, but, like other daughters of Eve, was not free from faults. For some indiscretion she was punished in accordance with Indian custom, which the following story, told by an early settler, Isaac Morse, will illustrate. One morning, Mr. Morse, on going into the timber to work, noticed a high pen built of poles around a large burr oak tree, in which was this Indian maiden. He asked her many questions, to which she made no reply, appearing sad and ashamed of her situation. At noon he offered her some of his lunch, but she would neither eat nor speak. Next morning, finding her still in the pen, Mr. Morse again tried to converse with her, and commenced pulling down the pen from around her. She then said that she was a bad Indian, consequently must stay there another day, and commenced repairing the pen around herself.

“Shaubena had a grandson named Smoke, a bright, intelligent lad, about thirteen years of age at the time of his death, and to him was bequeathed the chieftainship of the tribe. Smoke went to Kansas after his grandfather’s death, and is said to be chief of the band.“Shaubena has a nephew, a half-breed, named David K. Foster, who received a college education, and is now a Methodist preacher at Bradley, in Allegan county, Michigan. Also, another nephew, a half-breed and a college graduate, by the name of Col. Joseph N. Bourassa, now living at Silver Lake, Kansas. From each of these men I have received many letters, and to them I am indebted for many items given in this work.

“A few years before Shaubena’s death, he gave all his family Christian names, in addition to their Indian names, assuming the name of Benjamin himself.”

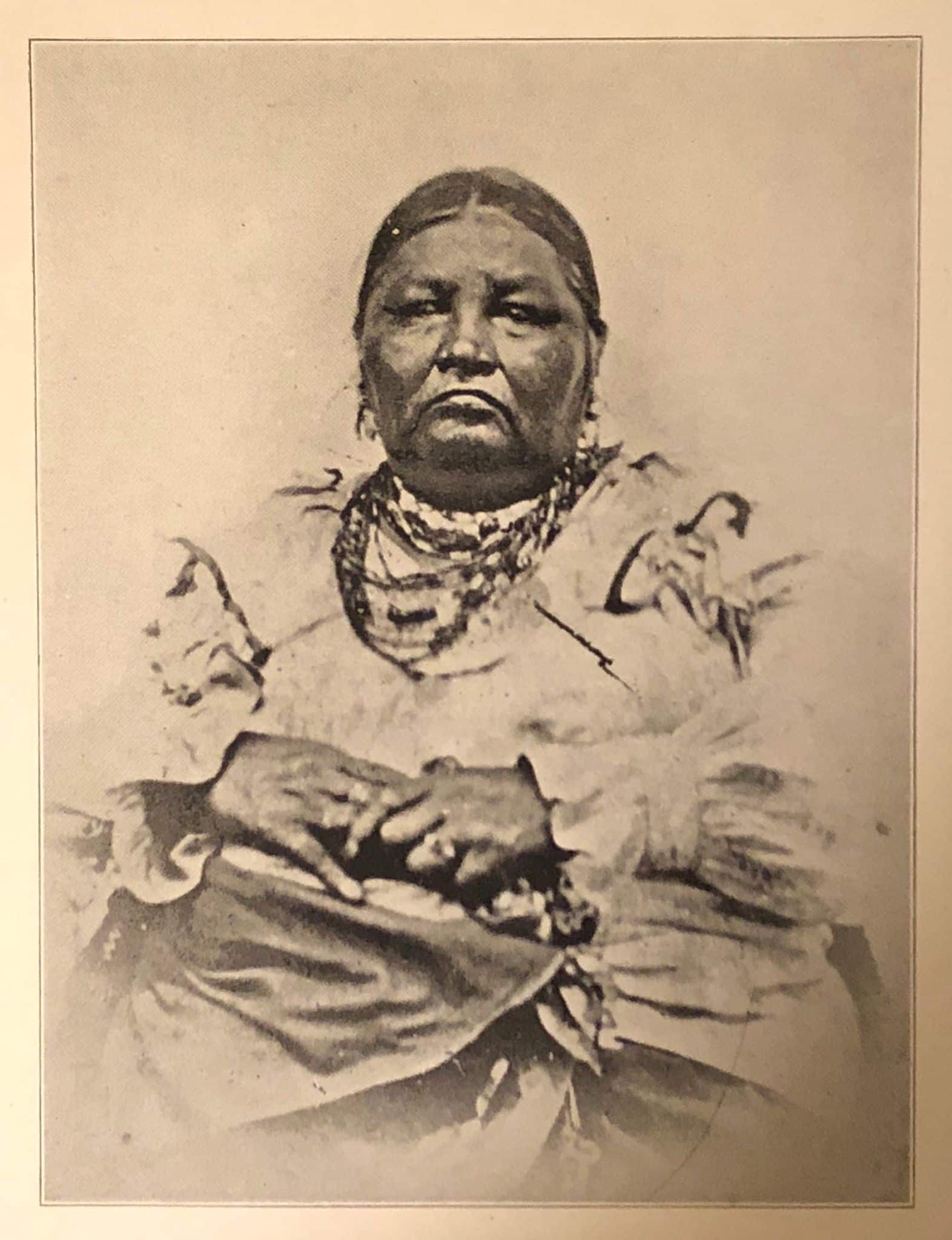

Following his death on 17 July 1859, Shabbona was a given a grand public funeral on 19 July and then buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Morris, Illinois. On 30 Nov. 1864, his widow Mi-o-mex and his granddaughter Mary Oquaka, age 4, accidentally drowned together in Mazon Creek in Grundy County. They were buried by his side.

Efforts to raise money for a grave monument were interrupted by the Civil War, so it was not until 1903 that a large inscribed boulder was placed at their final resting place. According to the 1886 compilation “Abraham Lincoln’s Vocations,” some years later Shabbona’s daughter and her son, John Shabbona, came from the reservation at Mayetta, Kansas, and visited Shabbona’s Grove, viewing photographs and documents pertaining to Shabbona in DeKalb and Chicago. In 1903, when Shabbona’s monument was laid, John Shabbona again returned to Chicago along with members of several of the expelled tribes of Illinois for a special Indian encampment recognizing the original peoples of Chicago (see “City Indian: Native American Activism in Chicago, 1893-1934,” 2015, by Rosalyn R. LaPier, David R. M. Beck, page 64).

NOTE: An earlier version of this article misidentified the Pottawatomi chief Topinabe as the same person as Daniel Bourassa, but Daniel Bourassa, a Frenchman of Michigan, cannot be identified as Chief Topinabe (see the article “Joseph and Madeline Bertrand” and other articles at the Chief Abram B. Burnett Family homepage). The spurious identification of Topinabe as Daniel Bourassa, found at Find-A-Grave and elsewhere on the internet, is due to the erroneous identification of the parentage of Madeline (Bourassa) Bertrand, whose mother was an unknown Native American woman.