Among the big changes that came to the Pekin Public Library when it moved into its very own building in 1903, the library that year also changed how it catalogued the books and magazines in its collection.

Shortly before Pekin’s Carnegie library opened to the public on Dec. 10, 1903, the staff of the library commenced the re-cataloguing of the materials in its collection, in order to bring the Pekin Public Library’s cataloguing system into agreement with the Dewey Decimal Classification System. Pekin’s library has used this system, with modifications over the years, ever since.

The Dewey Decimal Classification System was invented by Melvil Dewey (1851-1931) in the 1870s. Dewey was one of the founding members of the American Library Association (ALA), and he was a leader in promoting the use of library cards and card catalogs.

Prior to the introduction of Dewey’s classification system, libraries would assign a permanent number and shelf location in their stacks based on when the library acquired an item and what size it was. Some libraries also developed their own classification systems based on topic or author. Library stacks were normally closed to the public, and librarians themselves retrieved the books, periodicals, or pamphlets that patrons requested.

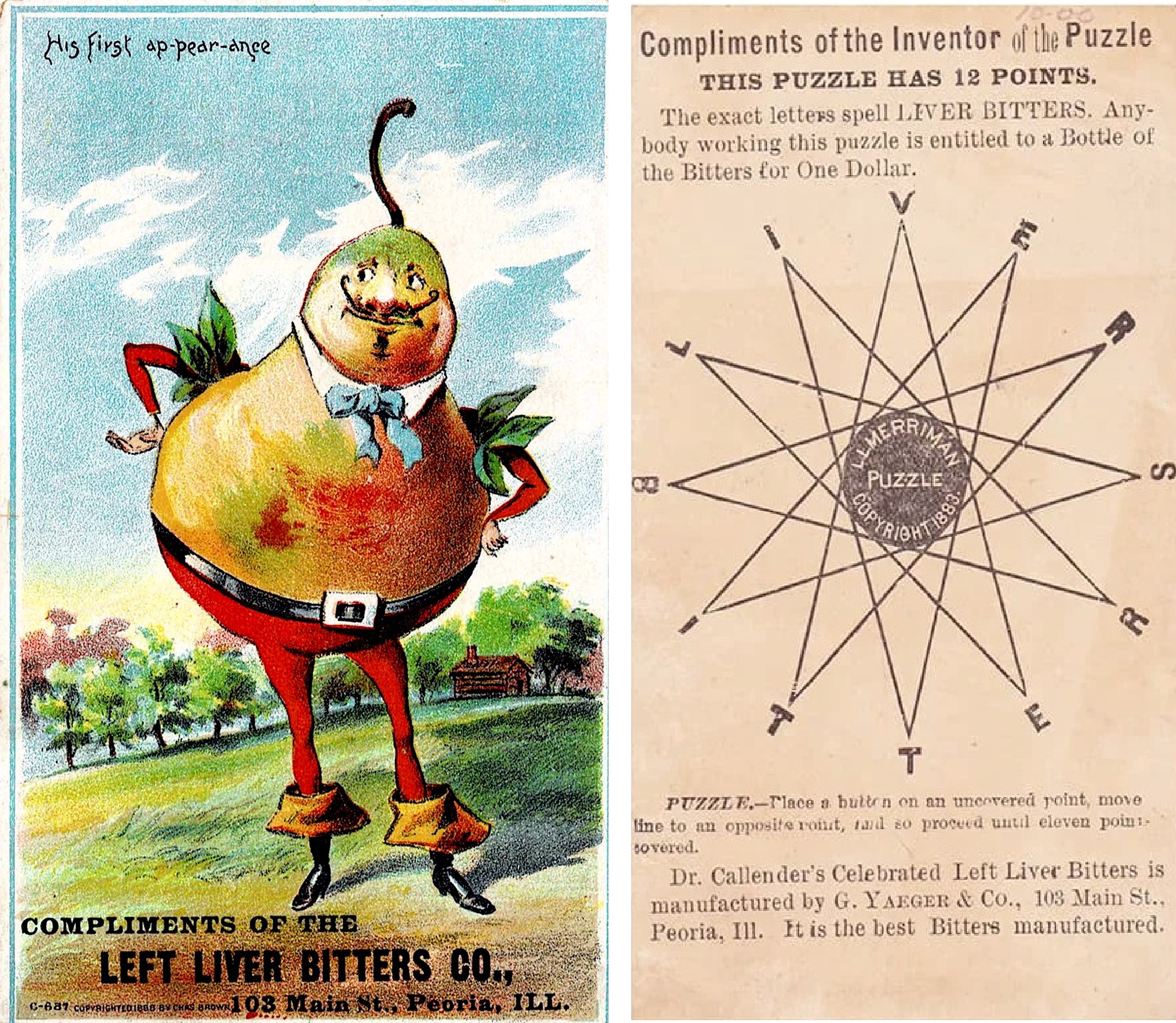

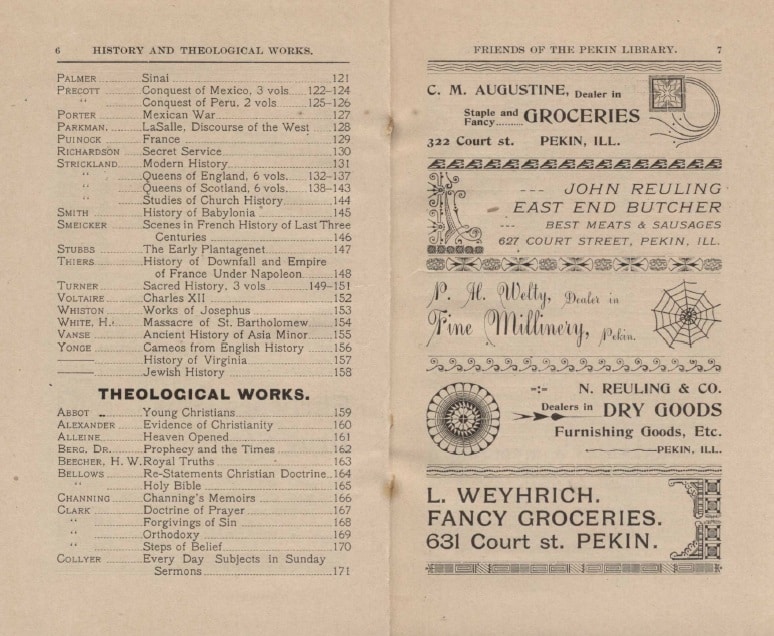

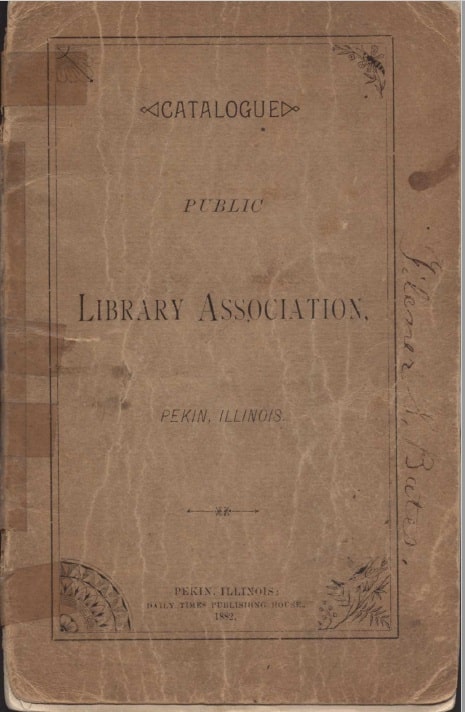

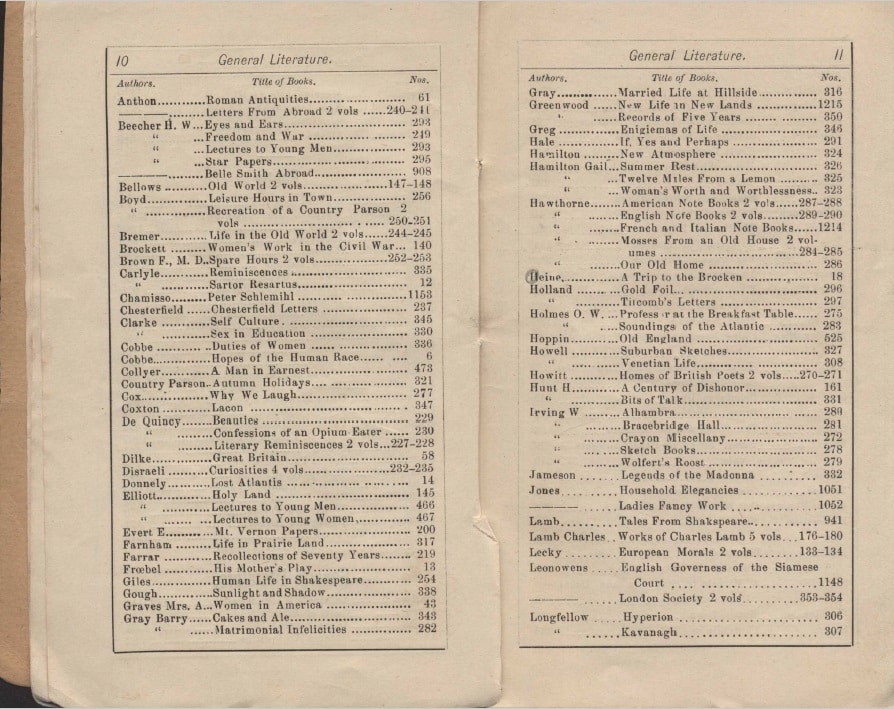

That is how the Ladies Library Association and Pekin Library Association operated, and it is also how the Pekin Public Library operated prior to Dec. 1903. The Pekin Public Library’s archives include some copies of an 1882 edition of the public catalogue of the Ladies Library Association of Pekin (printed by the Daily Times Publishing House), as well as a few copies of the public catalogue of the Pekin Library Association from the 1880s and 1890s (published by Pekin printer William H. Bates, and filled with advertisements of the numerous Pekin businesses that had sponsored the printing of the catalogue).

These catalogues and other mementos and relics of Pekin’s library history are currently on display in the Local History Room and in a display case under the stairs to the library’s second floor.

These public catalogues were pocket booklets that were given to library patrons so they would know what materials could be borrowed from the library’s collection. The catalogue indexes show that the materials must have been assigned numbers based on when the Library Association acquired them or based on an author’s surname, and only secondarily based on subject matter, because there is often little or no correlation between an item’s number and its subject.

Melvil Dewey wanted libraries to catalogue their materials using the concepts of “relative index” and “relative location,” in which books would be added to a library’s collection and assigned numbers based their subject matter and decimal numbers based on subtopic. To structure his cataloguing system, Dewey relied on the classification of the fields of human knowledge (or “sciences,” from the Latin word scientia, “knowledge”) that was proposed by Francis Bacon (1561-1626), an English Protestant natural philosopher who lived during the Renaissance. Bacon’s system was in turn derived and adapted from medieval Catholic philosophy, beginning with basic or general knowledge, then moving on to philosophy, then religion, then the various divisions of natural philosophy and natural science (including mathematics), followed by the arts (including music), literature (particularly poetry and drama), and finally biography and history.

The Dewey Decimal System is not the only classification system in use today, but it remains the most popular system in use in U.S. libraries. The other preeminent system used in the U.S. is the Library of Congress Classification System, which was originated around the same time as the Dewey Decimal System. During his lifetime, Dewey himself held the copyright to his classification system, but today it is owned and maintained by the Online Computer Library System (OCLC, formerly the Ohio Computer Library System).

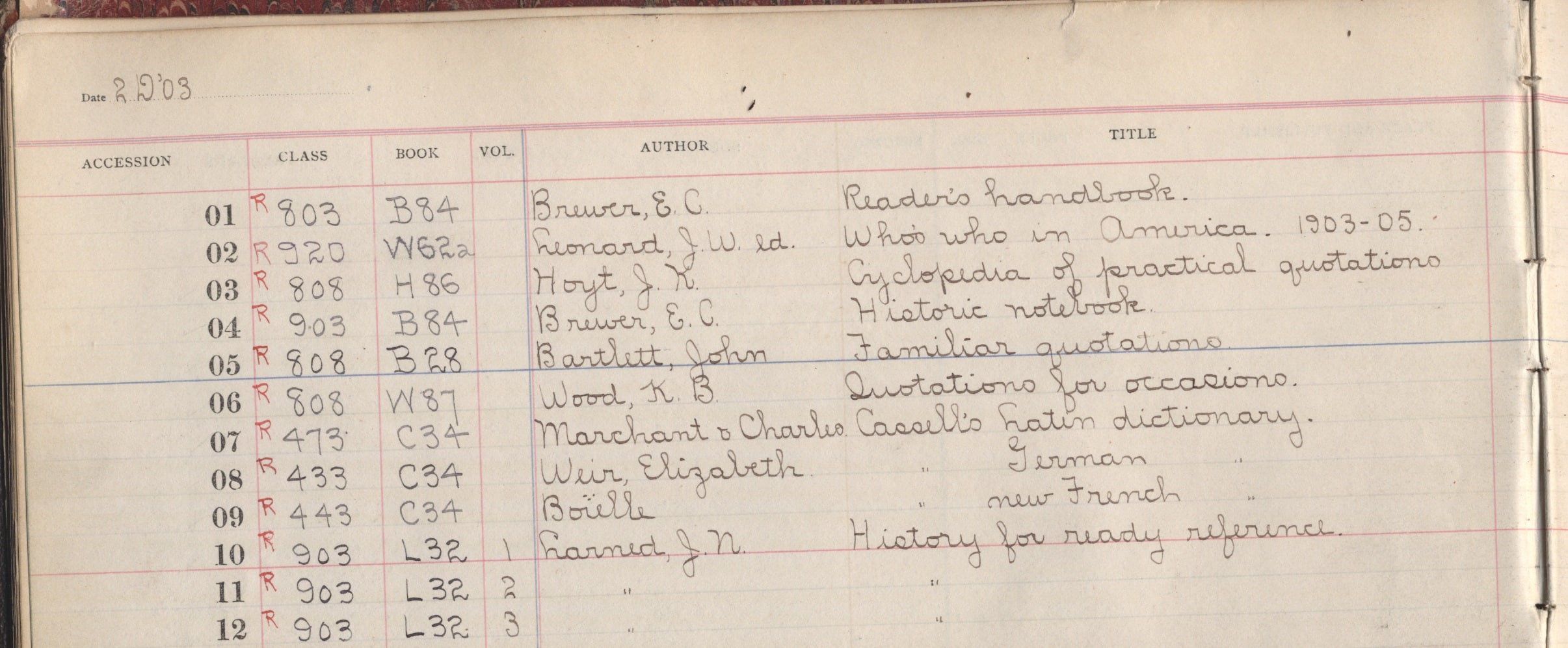

Before the system was computerized, libraries that used the Dewey system would record their materials and classification numbers by hand in large and heavy accession books, in which library staff would write each item’s date of acquisition and the date that an item was removed (“weeded”) from the collection. Pekin Public Library’s old accession books were kept on the shelves of our Local History Room for many years, but are now stored in our archives.

Our oldest Dewey accession book was begun on Dec. 2, 1903, just eight days before the Pekin Carnegie library opened to the public. The first item recorded in that book was E. C. Brewer’s 1,243-page “Reader’s Handbook” (1902), which was assigned the Dewey number “803” (literature).

The Pekin Public Library continues to use modified forms of the Dewey Decimal System in both its Adult and Youth Services areas. For those unfamiliar with the system, the library provides “Book Finder” pamphlets to help patrons narrow down their searches and aid in browsing.

Next week, we’ll review the library’s history during the first half of the 20th century.