This is a reprint of a “From the Local History Room” column that first appeared in September 2014, before the launch of this weblog.

In this column, we have previously told the story of the Great Chatsworth Train Wreck of 1887, which claimed the lives of a very large of residents of central Illinois, including residents of Tazewell County. Almost two decades after that, however, there was another train wreck in our area which many people lost their lives.

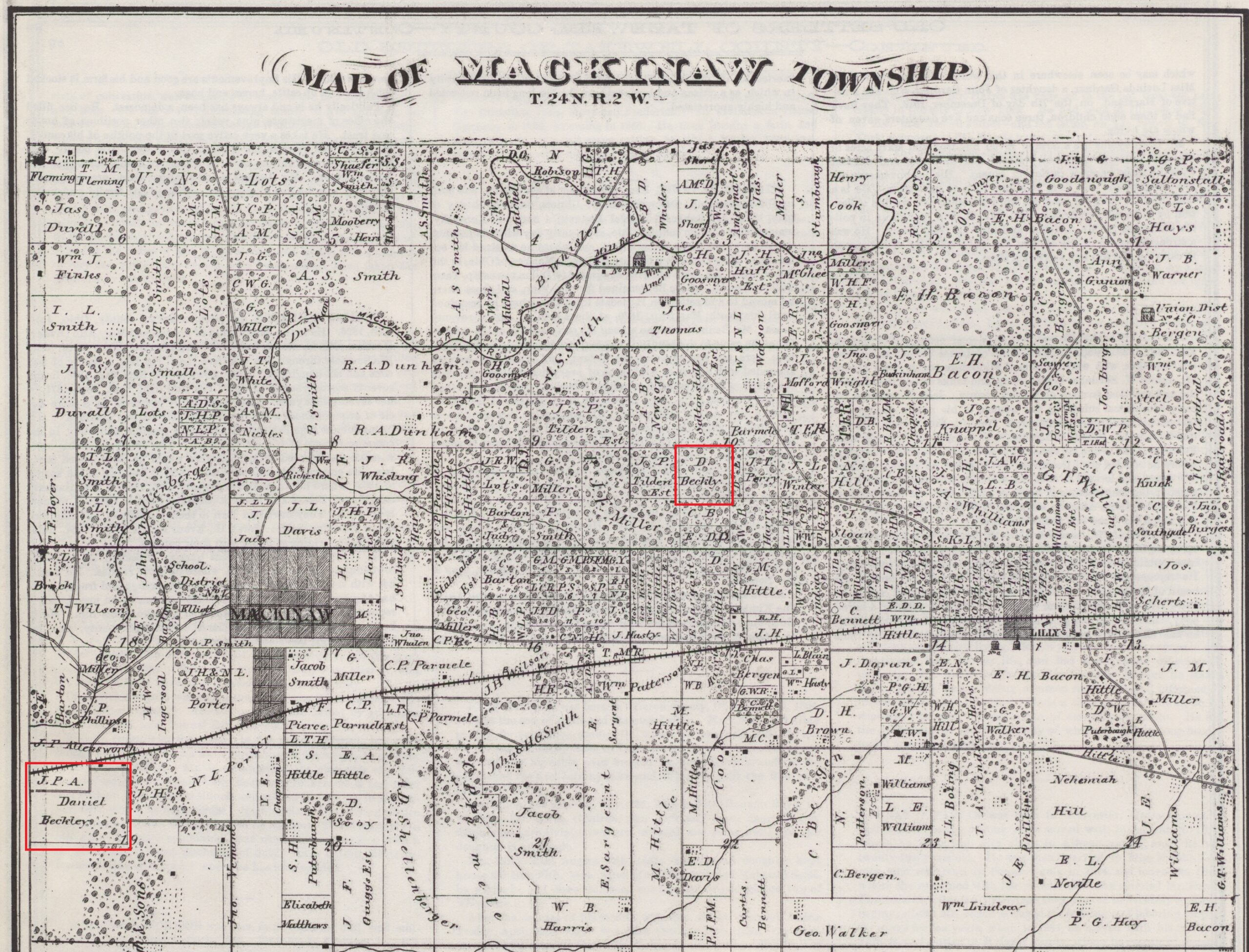

It was reported in newspapers at the time as the “Terrible wreck on the Big Four,” and it happened on Nov. 19, 1903, between Mackinaw and Tremont about three-and-a-half miles east of Tremont and about a mile west of Minier. In his 1905 “History of Tazewell County,” Ben C. Allensworth of Pekin called it “the most terrible disaster known in the history of railway accidents in Central Illinois, except the one which occurred at Chatsworth.” (In fact, newspapers used variations of the headline “Terrible wreck on the Big Four” several times over the years, whenever the Big Four suffered a major wreck.)

The accident made headlines across the country and even internationally. This is how the Gazette of Montreal, Canada, reported the news on the front page of its edition of Nov. 20, 1903:

“Peoria, Ill., November 19. – Thirty-one men were killed and at least fifteen injured in a head-on collision between a freight and a work train on the Big Four Railroad between Mackinaw and Tremont this afternoon. The bodies of twenty-six victims have been taken from the wreck, which is piled thirty feet high on the tracks. Five bodies yet remain buried under the huge pile of broken timber, twisted and distorted iron and steel.

“On a bank at the side of the track lie the bodies of the victims, cut, bruised and mangled in a horrible manner. So far twelve only have been identified, the remaining being unrecognizable.

“All the dead and most of the injured were members of the work train, the crews of both engines jumping in time to save their lives. The collision occurred in a deep cut, at the beginning of a sharp curve, neither train being visible to the crew of the other until they were within fifty feet of each other. The engineers set the brakes, sounded the whistle and leaped from their cabs, the two trains striking with such force that the sound was heard for miles.

“A second after the collision the boiler of the work train engine exploded, throwing heavy iron bars and splinters of wood 200 feet.

“Conductor John W. Judge, of Indianapolis, who had charge of the freight train, received orders at Urbana to wait at Mackinaw for the work train, which was due there at 2:40 p.m. Instead of doing this he failed to stop.

“The engineer of the work train, Geo. Becker, had also received orders to pass the freight at Mackinaw and was on the way to that station.

“After working two hours the remains of 26 men were taken out. One of the last bodies recovered was that of William Bailey, of Mackinaw, who had been lifted 30 feet into the air and held in place by two rails which had been pushed up between the engine and the tender of the work train.

“The injured were taken to the two cabooses of the relief trains, where temporary hospitals were improvised and their wounds taken care of. The dead will lie on the bank all night, or until the arrival of the coroner in the morning. The dead are residents of the neighboring towns and the scenes about the wreck this evening were beyond description. Wives and children of men who were missing thronged around, asking if their husbands or fathers had been killed. Out of 35 men who constituted the crew of the work train, only four are living and two of these are seriously injured.”

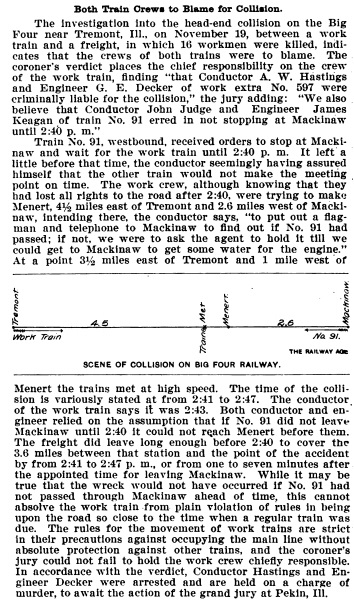

Although the Montreal Gazette report put the blame for the accident to the freight train, an inquest jury empaneled by Tazewell County Coroner Nathan Holmes blamed the crew of the work train. This is how Allensworth tells the story, on pages 812-813 of his Tazewell County history:

“A work train left Pekin on the morning of that day and proceeded to Tremont. The crew of this train was engaged in picking up old iron along the track and replacing rails which had been worn, and such other work as the condition of the road seemed to require at the time. They left Tremont in the afternoon some time after 2 o’clock in charge of Conductor Hastings and Engineer Becker, proceeding eastward until within one mile of the fatal spot. They were under the impression that the track would be clear and had received no orders to the contrary at Tremont.

“The regular freight from the east in charge of Conductor John Judge and Engineer James Kegan, was late at Mackinaw and was supposed not to leave Mackinaw until 2:40. The work train ran short of water and the engineer could not push his train back to Tremont, and concluded that he could reach the station of Minier in time to be safely on the switch before the regular train west could possibly reach the station.

“As fate would have it, the No. 95 or west-bound freight, made no stop at Mackinaw, having the ‘board.’ The evidence went to show that they must have been out at Mackinaw about 2:39 at a fairly good rate of speed. Understanding that this train would not leave Mackinaw until 2:40, the work-train was proceeding east when, without warning of any kind and in a curve, where neither train was visible to the other over 300 feet, the two engines came together with such powerful momentum that they were simply locked together, neither one leaving the track. The front cars of the work-train were loaded with heavy iron rails, upon which were sitting a number of workmen, there being thirty men, all told, on this train. The cars of No. 95 were also heavily loaded, and the shock was a most tremendous one. The wreckage was piled up in ‘hard-pan cut’ to the height of 35 to 40 feet. Death came almost instantaneously to some twelve or fourteen of the unfortunate victims, and the remainder, making a total of sixteen, died of their injuries shortly after. . . .

“Coroner Holmes was soon upon the ground and began the investigation with reference to fixing the blame for this appalling accident. . . . A number of days were consumed in taking evidence in the case, and the jury finally arrived at the conclusion that the blame lay with the crew of the work-train. As a consequence, Conductor Hastings and Engineer Becker were placed under arrest and held to the Grand Jury to meet the first Monday in December. . . This body of representative citizens of the county gave the matter a thorough investigation, and unanimously voted to find no bill against the accused.”