The date was Aug. 4, 1964. The time was just before noon. The place, the outlet canal of Commonwealth Edison’s Powerton Plant south of Pekin.

That is when and where Emil Petri, of 221 Henrietta St., who had gone down to the canal to do some fishing, made a gruesome discovery: a human skull embedded in the sand on the canal shore.

According to a Pekin Daily Times article on page 2 of the Aug. 6, 1964 issue, Petri took the skull home that day, then returned to the site the next day and started digging. He unearthed a partly decayed wooden box or crate – and within the box, a nearly complete human skeleton.

At that point, Petri left the box and the human remains at the site and went to notify the Tazewell County Sheriff’s Office, and, in accordance with state statute governing the discovery of human remains, the County Coroner Louis Imig was called to the scene. Imig requested the assistance of the Illinois State Police Crime Laboratory. Investigators retrieved not only the skeleton and the box, but a few associated relics.

The box or crate had apparently been deposited at that location at an unknown time in the past – Sheriff Arch Bartelmay Jr. said it looked like the box and skeleton had been in the water of the canal for more than 30 years. The Daily Times noted that the Powerton Plant had been built in 1928. The canal’s water level for most of 1964 had been high enough to keep the box and its contents submerged that year, but by July the water level had subsided, exposing the shore where Petri came upon the skeleton.

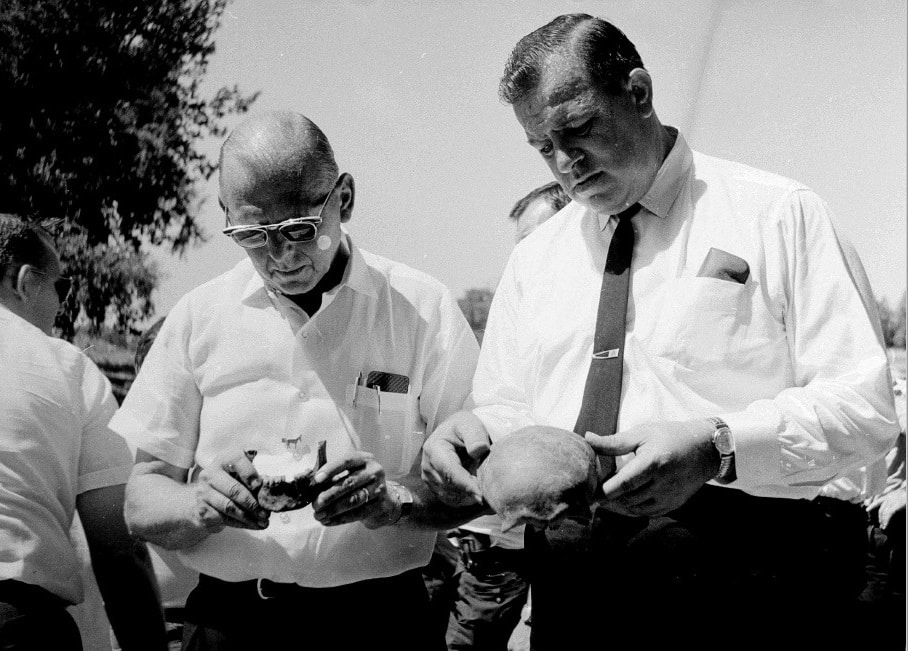

But whose mortal remains were they? How and when did the person die, who placed the bones in the crate, and how did the remains end up on the canal shore? To help with the investigation of the skeleton and the site where it was found, Imig and Sheriff Arch Bartelmay Jr. called in Dickson Mounds archaeologist Alan D. Harn, who studied the bones, the site, and the various relics. Crime Lab investigators also studied the remains, which were sent to Springfield for study. Imig, Bartelmay, and Harn then prepared a report, which was released to the public on Aug. 13, 1964.

The report’s findings were summarized by the Pekin Daily Times in an article that appeared on page 2 of the newspaper the same day. The Daily Times article, entitled “Report Says Skeleton Was Male in 20’s,” described the report’s findings as follows:

“Results of their examination show the skeleton to be that of a colored male in his early 20’s at time of death. The man was about 5-feet seven-inches tall and weighed between 130 and 160 pounds. The report said the teeth were badly worn for such an age, possibly due to a poor diet. They compared with those of a man 40 or 50 years old, according to the archaeologist. Only a few of the teeth were missing on the lower jawbone, the only section found.

“The skeleton, fairly complete, showed no broken bones and no indication of poison in the preliminary study. Bartelmay said archaeologists plan to analyze the wood of the box in which the bones were discovered . . . . He said that, because the wood had dried out in the sun, authorities had been unable to determine when the body was buried and will not be able to find out within 20 years, either way, of the exact time of death.

“Harms (sic) wrote that the heel of the lone moccasin-type shoe buried with the skeleton looked ‘peculiar.’ The shoe had a built-up sole.”

Bartelmay said more information ought to be forthcoming after examination of the skull. However, I have not found a follow-up report in a later issue of the Pekin Daily Times.

Based on what the newspaper article said, it probably wasn’t a case of homicide and the concealment of the body. Rather, the man may have died and been solemnly buried several decades before, perhaps even in the 19th century. Perhaps someone at some point – maybe during the construction of Powerton in 1928? – had discovered a forgotten, unmarked grave, and had decided to relocate the remains rather than notify the authorities. Harn at least was able to determine that he was an African-American man in his 20s, that he apparently didn’t have a good diet (and didn’t regularly see a dentist), and his shoes resembled moccasins.

But who he was, when he died, and how his remains ended up at that location, remain a mystery.