Continuing our review of what historical records can tell us of 19th-century African-American residents of Pekin, this week we move on to the period from the 1860s to the 1880s — the decades of the Civil War and its aftermath, when slavery finally was abolished and civil rights for blacks first began to be enshrined in law.

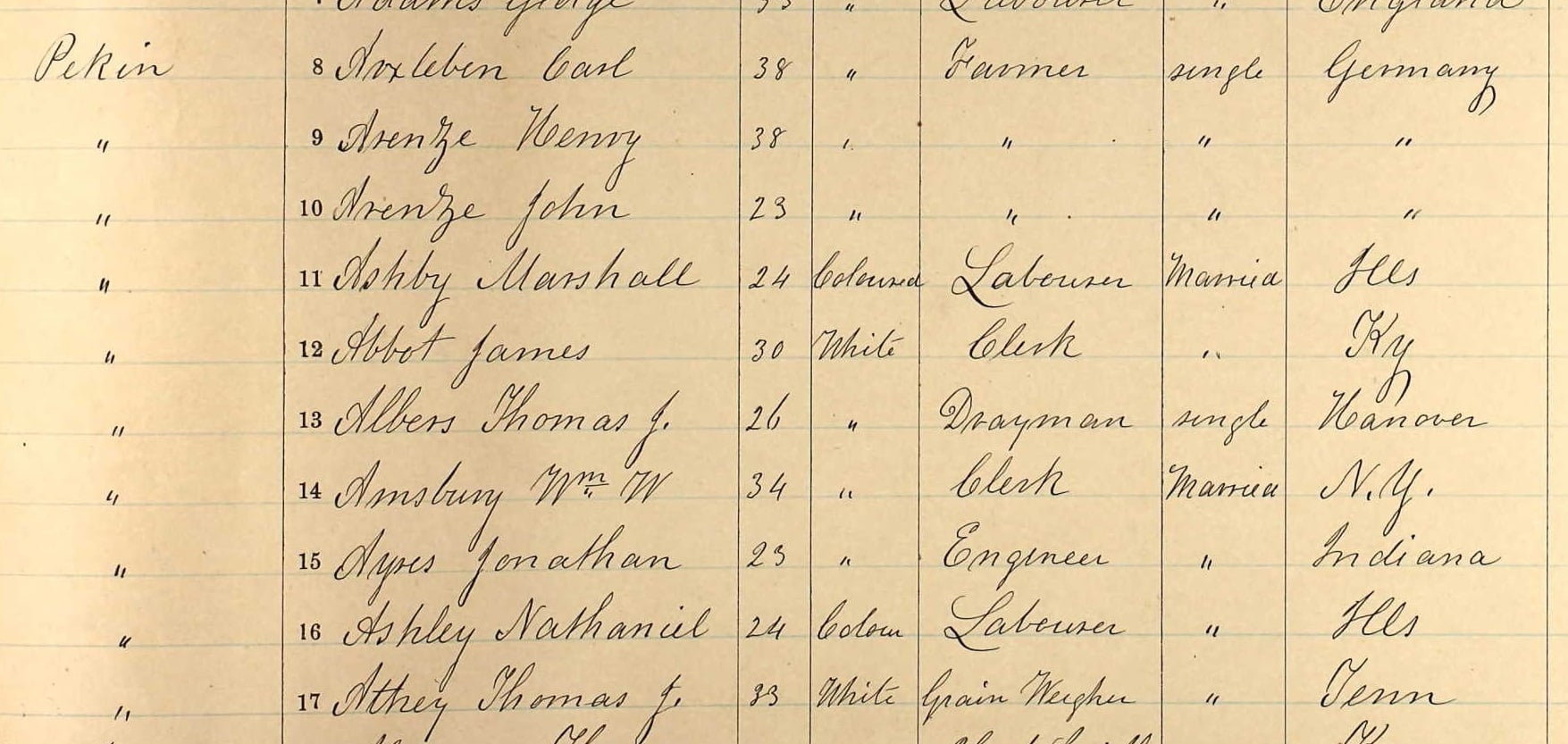

As we have seen, the numbers of African-Americans in Pekin were already quite low at the time of the 1850 U.S. Census. Ten years later, on the eve of the Civil War, their numbers were even lower. Only 18 African-Americans were enumerated as Pekin residents at the time of the 1860 U.S. Census. The number of Pekin’s African-Americans dropped to 10 in the 1870 census, but increased to 19 in the 1880 census.

One of Pekin’s few African-Americans in 1860 was Malinda Cooper, 19, “mulatto” (i.e. mixed-race), born in Illinois, a servant in the household of Daniel and Mary Bastions. Also living with the Bastions at that time was a white girl named Mary or May Warfield, 11, born in Illinois – we’ll hear more about Mary Warfield further on.

Pekin in 1860 was also the home of the “mulatto” family of Virginia-born John Brown, 44, a barber, who is enumerated in the census with his wife Charlotte, 43, and children or grandchildren George W., 20, Caroline M., 20, and Amanda, 3.

The 1860 census also shows a black family living in Pekin, headed by Virginia-born Edward Hard, 29, “black,” a laborer, whose wife Elizabeth Hard, 28, “mulatto,” and one-month-old daughter Mary, are listed in the house with Edward. A year later, the 1861 Roots City Directory of Pekin lists “Howard Edward (colored), laborer, res. Market, ss. 1st d. e. Third” – apparently the same man as “Edward Hard” of the 1860 census. The 1870 U.S. Census for Pekin enumerates the family of Kentucky-born “Edwin Howard,” 45, black, a fireman in a distillery, with his wife Elizabeth, 49, and their daughters Melinda, 10, and Elizabeth, 6 months. “Edwin” is, again, apparently the same man as “Edward” Howard or Hard. Living in the Howard household at the time of the 1870 census was Alabama-born Allen T. Davison, 23, black, a fireman in a distillery, and his wife Sarah J. Davison, 18.

The same year, the 1870 Sellers & Bates City Directory of Pekin shows “Howard Ed., (colored), laborer, res ne cor Front and Isabella.” Six years after that, the 1876 Bates City Directory of Pekin shows “Howard Edwin, (col) fireman distillery, res ns Isabel 1d e Front,” and shows Allen T. Davison as “Davison Travis, foreman distil’ry, res ns Isabel 1d w Second” (“foreman” an error for “fireman”). Four years later, Allen Travis Davison is counted in the 1880 U.S. Census of Pekin as “Travis Davis-Son” (sic), 33, then rooming in the house of the white family of Edward and Mary Elster at 117 Court St. (the census taker erroneously read the “-son” of Travis’ surname to mean that Travis was a son of Edward and Mary).

Travis Davison does not appear as a resident of Pekin after 1880, but his former neighbor Ed Howard appears one more time – in the 1887 Bates City Directory of Pekin, he is listed as “Howard Edwin, barber 233 Court, res. 101 Isabel.”

Going back to the 1860 U.S. Census, besides the family of Benjamin and Nance Costley, the only other African-Americans of Pekin listed in that census are Moses “Mose” Ashby, 23, and his brother William Ashby, 21, both born in Illinois and identified as “mulatto.” Mose and William were then laborers living in the household of Peter and Margaret Devore. Besides Moses and William, records show two more of their brothers living in Pekin around this time: Nathaniel (or Nathan) Ashby and Marshall Ashby. The 1861 Roots City Directory of Pekin lists “Ashby Moses (colored), livery hand, Margaret, ns., 1st d. e. Front; res. Ann Eliza, ss., 1st d. w. Third” and “Ashby Nathan (colored), teamster, Ann Eliza, ss., 1st d. e. Second; res. river bank, foot of State.”

Their brother William is listed in the 1870 U.S. Census of Pekin as William J. Ashby, 27, born in Illinois, “mulatto,” a teamster, with his wife Sarah, 30, and children Lewis, 3, and Catharine, an infant. Living with them was a white girl named Laura Correl, 14. Ten years later, William is listed in the 1880 census at 172 Caroline St., as “William Asbey,” 37, black, with his wife Sarah, 45, and children Louis, 13, Catharine, 10, Sarah, 7, and Charles, 7. William next appears in Pekin in the 1887 city directory: “Ashby William J. lab. Res. 127 Caroline.” Listed right before William in that directory is “Ashby Charles, cigar mkr. Moenkemoeller & Schlottmann, res. 127 Caroline.” That seems to be William’s son Charles, who then would have been about 15. The last time William appears in Pekin is in the 1900 census, when he was listed as a 63-year-old coal miner, able to read and write, and a widower.

The four Ashby brothers were the sons of William Ashby, born in Virginia, who lived in Liverpool in Fulton County, Illinois. During the Civil War, his three sons William J., Marshall, and Nathan are known to have taken a stand in defense of human liberty by serving in the U.S. Colored Troops. Nathan and Marshall both registered for the Civil War draft on in June 1863 (but Nathan’s draft registration calls him “Nathaniel Ashley”). Nathan is listed in the 1870 Pekin city directory as “Ashby Nathan (colored), fireman, res ne cor Mary and Somerset.” The city directories and censuses do not show Nathan in Pekin after that – he later died at age 60 in Bartonville on July 31, 1899, and was buried in the defunct Moffat Cemetery on Peoria’s south side. Nathan had married a certain Elizabeth Warfield (perhaps related to Mary Warfield?) in Peoria County in 1860.

Marshall’s and Nathan’s military records say they were born in Fulton County, Ill., and that they served in Company G of the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry, enlisting at Springfield on Aug. 21, 1864, and being mustered in there on Sept. 21, 1864, and being honorably discharged at the Ringgold Barracks in Texas on Sept. 30, 1865. Significantly, Marshall, Nathan, and their company were in Texas at the time of the first “Juneteenth,” so it is quite possible that they were present in Galveston for Juneteenth, as their fellow Pekin Civil War veteran Private William H. Costley, of the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry, Company B, certainly was. Nathan applied for a Civil War pension in 1890, and his widow Elizabeth applied for widow’s benefits on Sept. 18, 1899.

Though Marshall had fought honorably for the unity of his nation and the freedom of his people, it was not long after his return to Pekin that he was reminded the hard way that, even at that late date, Illinois still did not allow interracial marriage. On March 14, 1866, in Tazewell County, Marshall married a white woman named Mary Jane Luce (or Lewis). Marshall’s wife first appears in the 1850 U.S. Census as Mary J. Luce, 5, born in Ohio, living in Peoria with her baby brother Elias Luce in the household of Isaac and Mary Holiplain. Ten years later, the 1860 census shows Mary working in Pekin as a live-in servant in the household of Daniel and Barbara Clauser.

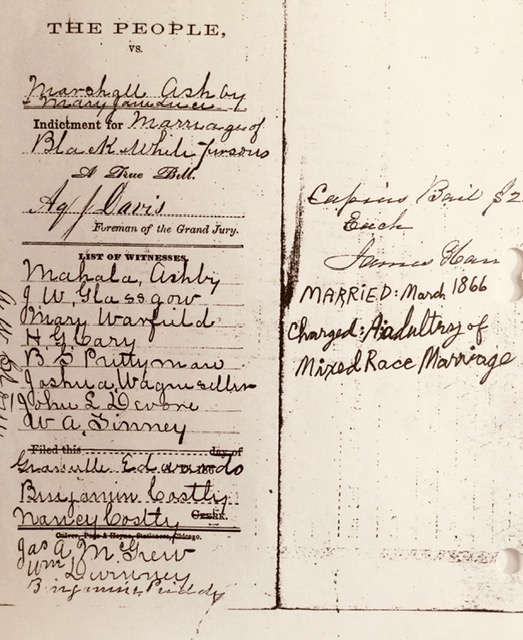

Marshall’s 1863 Civil War draft record says he was then married, but apparently Marshall’s then wife (whose name is unknown) had died before 1866 when he married Mary Luce. After the marriage, Mary Warfield (mentioned earlier in this column) informed the authorities that Marshall and his wife Mary were not the same race. A Tazewell County grand jury therefore indicted them for “marriage of black & white persons,” which Illinois state law then classified as a kind of adultery. Besides Warfield, the witnesses summoned to testify before the grand jury in this case were Mahala Ashby (perhaps Marshall’s mother, sister, or aunt), J. W. Glassgow, H. G. Gary, Benjamin S. Prettyman, Joshua Wagenseller (the noted Pekin abolitionist and friend of Abraham Lincoln), John L. Devore, Granville Edwards, Benjamin and Nance Costley, William A. Tinney (a past Tazewell County sheriff and friend of the Costleys who is remembered as an advocate for African-American voting rights), James A. McGrew, William Divinney, and Benjamin Priddy. Marshall and Mary were probably found guilty, and it is likely no coincidence that Marshall does not appear on record in Illinois after 1866.

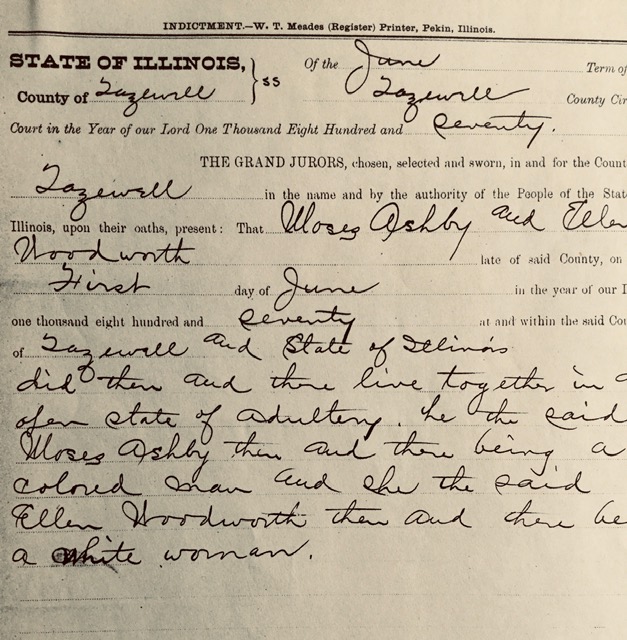

Despite what had happened to his brother, on June 1, 1870, Mose Ashby married an Illinois-born white woman, Ellen Woodworth, 24, resulting in a grand jury indictment that they lived “together in an open state of adultery” (i.e., he was black and she was white). The outcome of their case is uncertain, but exactly one month after their marriage the U.S. Census shows “Ellen Woodworth” working for Tazewell County Sheriff Edward Pratt as a domestic servant in the Tazewell County Jail – whether that was simply her job or she was serving her sentence for “adultery” is unclear.

The state law under which Marshall and Mose were indicted was approved by the General Assembly in 1829 as a part of Illinois’ old “Black Code” restricting the rights of free blacks in Illinois. The ban on interracial marriage, last of the Black Code statutes, was finally repealed in 1874, just four years after Mose’s indictment.

Census and directory records show an African-American couple living in Pekin in and about the year 1870. The only “colored” barber listed in the 1870-71 Sellers & Bates City Directory of Pekin was Frank Lawrence, who is listed in the directory as “Lawrence Frank (colored), barber, res and shop ss Court 4 d e Front” — residence and barbershop on the south side of Court St., four doors east of Front St. The 1870 U.S. Census shows him as Frank Lawrence, 29, born in Pennsylvania, “mulatto,” barber, with his wife Cornelia Lawrence, 20, born in Illinois, “mulatto,” keeping house. Living and working in the same household was Frank’s business partner Anderson Hayes, 32, born in Ohio, “mulatto,” barber. Frank and Cornelia were married in Knox County, Illinois, on 12 March 1869. I can find no other information on Frank and Anderson, but Cornelia, whose full name was Cornelia Ann (Hill) Lawrence, was the daughter of Augustus and Jane (Hudson) Hill, who were married at Peoria’s African Methodist Episcopal Church on 15 April 1847. Augustus and his family are listed in the 1850 U.S. Census of Peoria, but by 1860 the Hills were in Joliet, where Augustus worked as a whitewasher, and later seem to have moved to the Galesburg area, where Cornelia and Frank probably met, moving to Pekin after their marriage. What became of them after 1871 I have not yet determined.

Next time we’ll take a closer look at Pekin’s African-American residents in the period from about 1880 to the early 1900s.