This month in which we have observed President Abraham Lincoln’s 211th birthday is an ideal time to take a look back to the life of the 16th president of the United States, with a special focus on one of Lincoln’s local connections in Tazewell County.

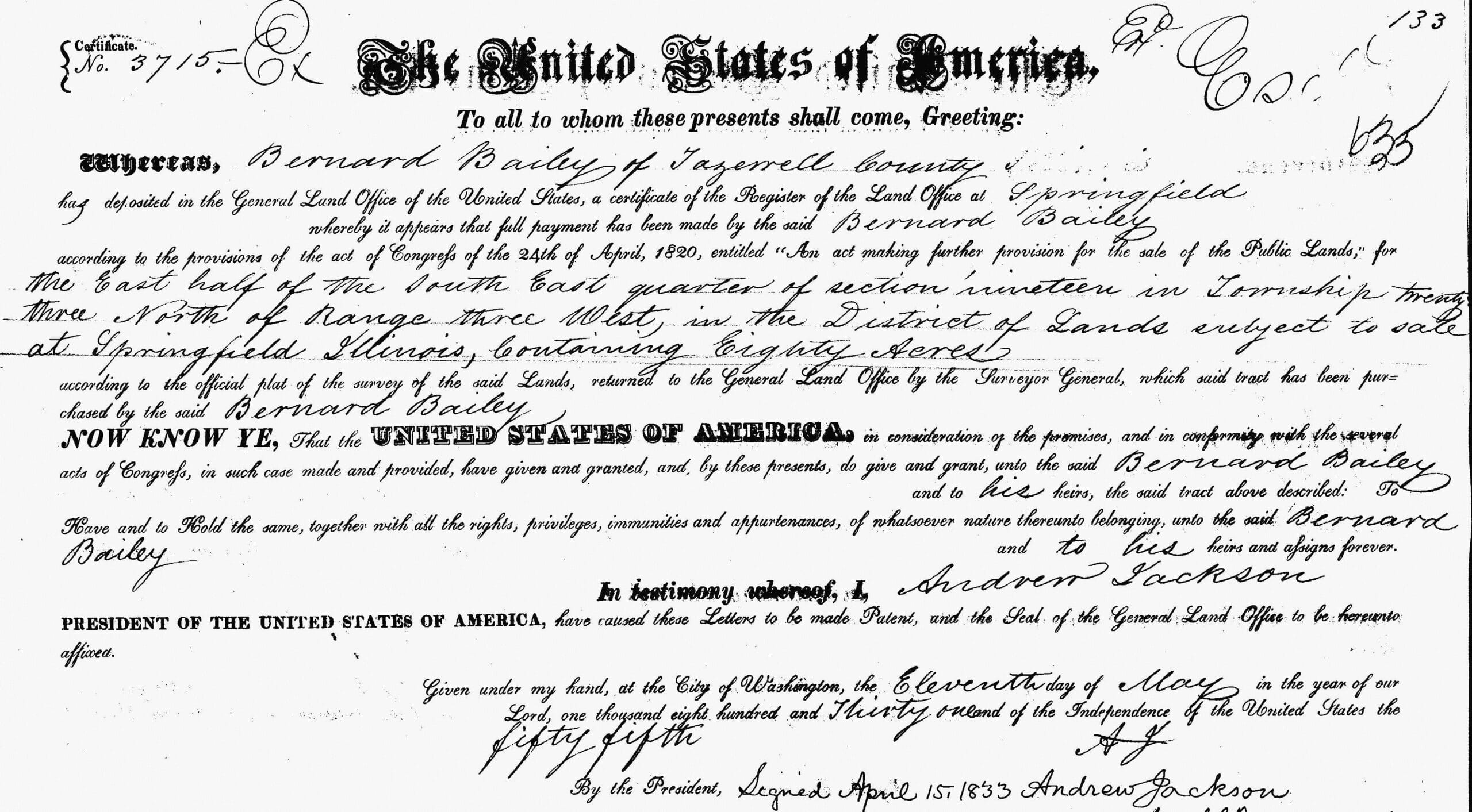

In this column space, we have previously reviewed some of the places and events in Tazewell County to which Lincoln had a connection. Often these connections are relatively minor or obscure, some are mundane, and some are more significant, such as Lincoln’s involvement in the 1841 case of Bailey vs. Cromwell, that secured the freedom of “Black Nance” Legins-Costley and her three eldest children.

At times local memories of Lincoln’s connections to Tazewell County have been garbled with the passage of time. One such garbled memory has to do with the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858: namely, whether or not – and when or where – Lincoln gave a speech in Pekin in the context of the famous debates during the U.S. Senatorial campaign of 1858, when the anti-slavery Lincoln, a Republican, attempted to unseat incumbent Sen. Stephen Douglas, who was a pro-slavery Democrat.

Pekin, of course, was not one of the seven sites where Lincoln and Douglas debated issues related to the institution of slavery and whether or not black Africans should have civil equality with Americans of white European origin. However, the old Pekin Centenary volume, on pages 15 and 17, says Lincoln and his fellow abolitionist politician, U.S. Senator Lyman Trumbull, came to Pekin on Wednesday, Oct. 6, 1858, and addressed a large crowd in the court house square.

That would have been toward the end of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. In fact, it would have been just one day before Lincoln and Douglas debated in Galesburg, which was the fifth of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. It is highly unlikely that Lincoln could have spoken in Pekin one day and then traveled to Galesburg to take part in a debate the very next.

Other recollections of Lincoln’s 1858 speech in Pekin give a different date. For example, Ernest East in his “Abraham Lincoln Sees Peoria” (1939), page 33, says, “The Peoria House again on the night of Tuesday, Oct. 5, 1858, was a stopping place for Lincoln. He occupied room No. 16 which five days earlier had been occupied by Stephen A. Douglas. Lincoln spoke in Pekin in the afternoon . . . Lincoln left Peoria on the morning of October 6. His movements for the day are not fully known but he reached Knoxville in the evening in a violent storm.”

On this subject, the Feb. 2020 issue of Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society “Monthly”, page 2717, reprints a short article from the Bloomington Pantagraph (Tuesday, March 17, 1896), entitled, “Mr. Lincoln’s Pekin Speech.” That 1896 article reads as follows:

“In the controversy about when Hon. Abraham Lincoln spoke in Pekin and whether in joint debate, Mr. Edward Roberts, an old settler at Mackinaw, says he feel sure it was the last of October, 1858, and that he spoke from the front porch of Mr. Joyce Wagonseller’s (sic – Joshua Wagenseller) dwelling, and was introduced and entertained by Mr. Wagonseller. It was not a joint debate but Mr. Lincoln spoke one day and Mr. Douglas the next.

“Mr. George Patterson, another old settler, corroborates this statement. They both went to Pekin purposely to hear this speech and heard it from beginning to end. He also spoke in Tremont the last of August the same year. Mr. Roberts heard this speech also, and had the honor of eating at the same table with Mr. Lincoln. He remembers Mr. Lincoln making the remarks when he went to get up from the table, that he could hardly get his long legs from under it, the table being quite low. The bench they sat on, rather high, made the sitting posture very uncomfortable for a long-legged person.”

This account of Lincoln’s Pekin speech provides a different date – Sunday, Oct. 31, 1858, rather than Wednesday, Oct. 6, 1858 – and a different location – the front steps of Joshua Wagenseller’s dwelling, not the court house square. In these recollections there is also no reference to Trumbull speaking with him.

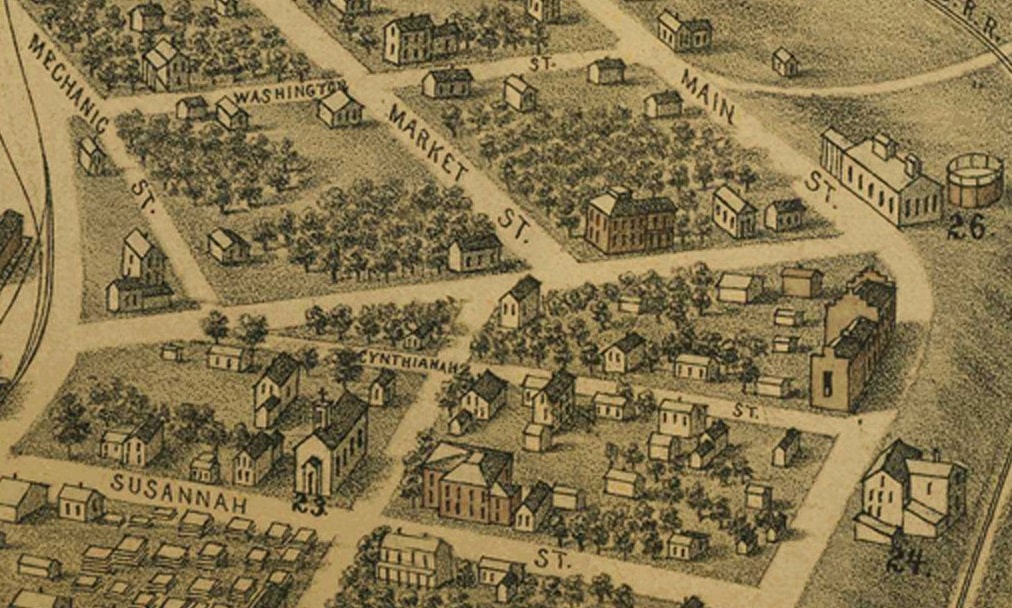

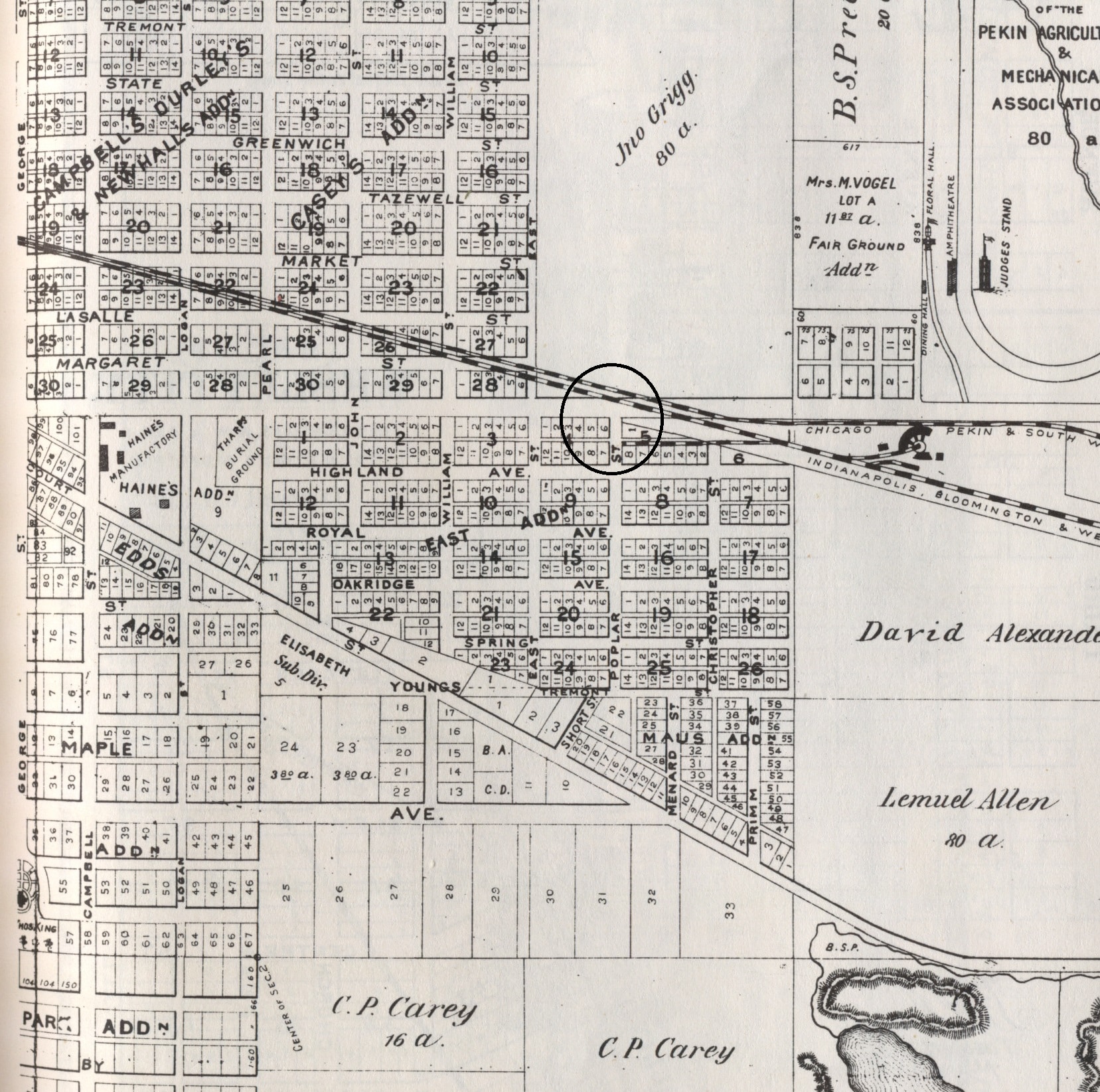

The 1861 Root’s City Directory of Pekin, page 60, says Joshua Wagenseller then lived at the southwest corner of Broadway and “Market.” At first glance, the description of that location is nonsensical, because present-day Market Street does not intersect with Broadway. During the 1870s, however, present-day Market Street did intersect with Broadway approximately where Broadway and 14th Street intersect today — more specifically, the corner of Sycamore and Broadway. That would seem to place Lincoln’s Pekin speech at the far eastern end of town, almost the opposite of what the 1949 Pekin Centenary reported.

That, however, is not where the Wagenseller house was located. In those early days, Pekin very confusingly had TWO Market Streets. Besides the one we’re familiar with today, there was a completely different Market Street in Cincinnati Addition, running south from Broadway — that stretch of roadway is today part of Second Street. It was there, at the southwest corner of Broadway and Second, that Joshua Wagenseller’s grand house was situated. The house is long gone, and today that spot is at or near the parking lot of Wieland’s Lawn Mower Hospital, which itself is next-door to the former Franklin Grade School. (My thanks to Wagenseller’s descendant Dan Toel and to Connie Perkins for their assistance in clarifying and correcting this matter.)

Why did Pekin have two different Market Streets? Probably because Cincinnati Addition had originally been platted to be a separate, rival town to Pekin, and only became a part of Pekin later. Cincinnati’s Market Street kept its old name for a few decades even after Cincinnati was annexed by Pekin, which had its own Market Street.

The recollections of Roberts and Patterson would place this speech 16 days after the seventh and final of the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and just two days before Election Day. This is may be more plausible than the statement in the Pekin Centenary, but East’s account placing the speech on Oct. 5 rather than Oct. 6 is also geographically and chronologically plausible. The Centenary’s statement would seem to be off by only one day, and appears to be a garbling of Lincoln’s Pekin speech of 1858 with his more famous Peoria speech of 1856, when Lincoln was indeed joined by Sen. Trumbull.

In fact, we can confirm that East’s date is the correct one, because a news report in the Oct. 5, 1858 Peoria Transcript (reprinted in the 6 Oct. 1858 Chicago Press & Tribune) tells us that Lincoln’s speech in Pekin was on Oct. 5, 1858:

“Mr. Lincoln was welcomed to Tazewell county and introduced to the audience by Judge Bush [John M. Bush, probate judge in Pekin] in a short and eloquently delivered speech, and when he came forward, was greeted with hearty applause. He commenced by alluding to the many years in which he had been intimately acquainted with most of the citizens of old Tazewell county, and expressed the pleasure which it gave him to see so many of them present. He then alluded to the fact that Judge Douglas, in a speech to them on Saturday, had, as he was credibly informed, made a variety of extraordinary statements concerning him. He had known Judge Douglas for twenty-five years, and was not now to be astonished by any statement which he might make, no matter what it might be. He was surprised, however, that his old political enemy but personal friend, Mr. John Haynes [sic – James Haines] — a gentleman whom he had always respected as a person of honor and veracity—should have made such statements about him as he was said to have made in a speech introducing Mr. Douglas to a Tazewell audience only three days before. He then rehearsed those statements, the substance of which was that Mr. Lincoln, while a member of Congress, helped starve his brothers and friends in the Mexican war by voting against the bills appropriating to them money, provisions and medical attendance. He was grieved and astonished that a man whom he had heretofore respected so highly, should have been guilty of such false statements, and he hoped Mr. Haynes was present that he might hear his denial of them. He was not a member of Congress he said, until after the return of Mr. Haynes’ brothers and friends from the Mexican war to their Tazewell county homes—was not a member of Congress until after the war had practically closed. He then went into a detailed statement of his election to Congress, and of the votes he gave, while a member of that body, having any connection with the Mexican war. He showed that upon all occasions he voted for the supply bills for the army, and appealed to the official record for a confirmation of his statement.

“Mr. Lincoln then proceeded to notice, successively, the charges made against him by Douglas in relation to the Illinois Central Railroad, in relation to an attempt to Abolitionize the Whig party and in relation to negro equality.

“After finishing his allusions to the special charges brought against him by his antagonist, Mr. Lincoln branched out into one of the most powerful and telling speeches he has made during the campaign. It was the most forcible argument against Mr. Douglas’ Democracy, and the best vindication of and eloquent plea for Republicanism, that we ever listened to from any man.”

One question yet remains: Did Lincoln deliver his 5 Oct. 1858 speech at Wagenseller’s home, or at the courthouse square as the Centenary claims. Unfortunately the above-quoted contemporary report does not explicitly say where the speech took place. The courthouse square would seem a more logical place for such an event. Even so, the “History of the Wagenseller Family,” compiled by George R. Wagenseller Sr., says that Lincoln was frequently a houseguest of Joshua Wagenseller – who was one of Pekin’s ardent abolitionists – and that Wagenseller even invited Lincoln to treat his home as his Pekin headquarters.

The same history asserts that Lincoln gave several speeches at different times from the second-floor balcony of the Wagenseller house. Thus, it would make sense that he might address a gathered crowd in that place on 5 Oct. 1858. Nevertheless, the recollections of pioneers sometimes grew hazy with time, and that is what happened in this case — Roberts and Patterson probably confused another talk Lincoln gave at the Wagenseller house with Lincoln’s Pekin speech of 1858, which did take place in the Tazewell County Courthouse square, as we may read in the following article from The Tazewell Register, Thursday, Oct. 7, 1858 (reprinted in the TCGHS Monthly, Oct. 2007, pages 1449-1451 (emphasis added):

The “Lincoln Rally”

Mr. Lincoln met with a very cordial reception from his friends on Tuesday [Oct. 5], and if they are satisfied with the demonstration, we see no reason why democrats should not be. The procession, numbering about one hundred teams, averaging six persons to a team — one third of whom however, were not voters — passed through the streets several times, and finally brought up at the court-house square, where Mr. Lincoln, accompanied by his abolition friend Webb and others, mounted the stand. T. J. Pickett gave the cue for “three cheers;” after which Judge Bush delivered an address of welcome suitable to the occasion. Mr. Lincoln spoke for about two hours, and then left for Peoria on his way to Galesburg, where he has a discussion today with Judge Douglas.

The crowd in town was easily estimated, and we think we are liberal enough allowing three thousand, including men, women, and children. Of course, besides the democrats, there was a large number of old line whigs present who have no idea of amalgamating with abolitionists, even to oblige Mr. Lincoln.

Trumbull was not here to take the place assigned in the bills, but Judge Kellogg was on hand, and spoke in the courthouse at night. We were not present, but understand he appeared as the peculiar advocate and representative of Lyman Trumbull, and repeated the charges for which Judge Douglas had branded Trumbull as “an infamous falsifier.”

We have conversed with a number of democrats who were in town on Tuesday and Saturday, and they assure us that the two meetings demonstrate beyond a doubt that the county is sure to go for Douglas.

From this report, it is clear that the the 1949 Pekin Centenary’s statements regarding Lincoln’s speech in Pekin were mistaken not only in the date (Oct. 5, not Oct. 6) and in stating that Trumbull was present on the occasion. The mistake regarding Trumbull’s presence was perhaps due to the fact that printed handbills advertising the planned speech had said Trumbull would be there. The author of the Centenary text have have based his statement on what was said in the handbills.

NOTE: The day after publication, this article was updated, augmented and corrected with additional information and images. The assistance of Dan Toel and Connie Perkins is especially appreciated.