This is a reprint of a “From the Local History Room” column that first appeared in November 2014 before the launch of this weblog.

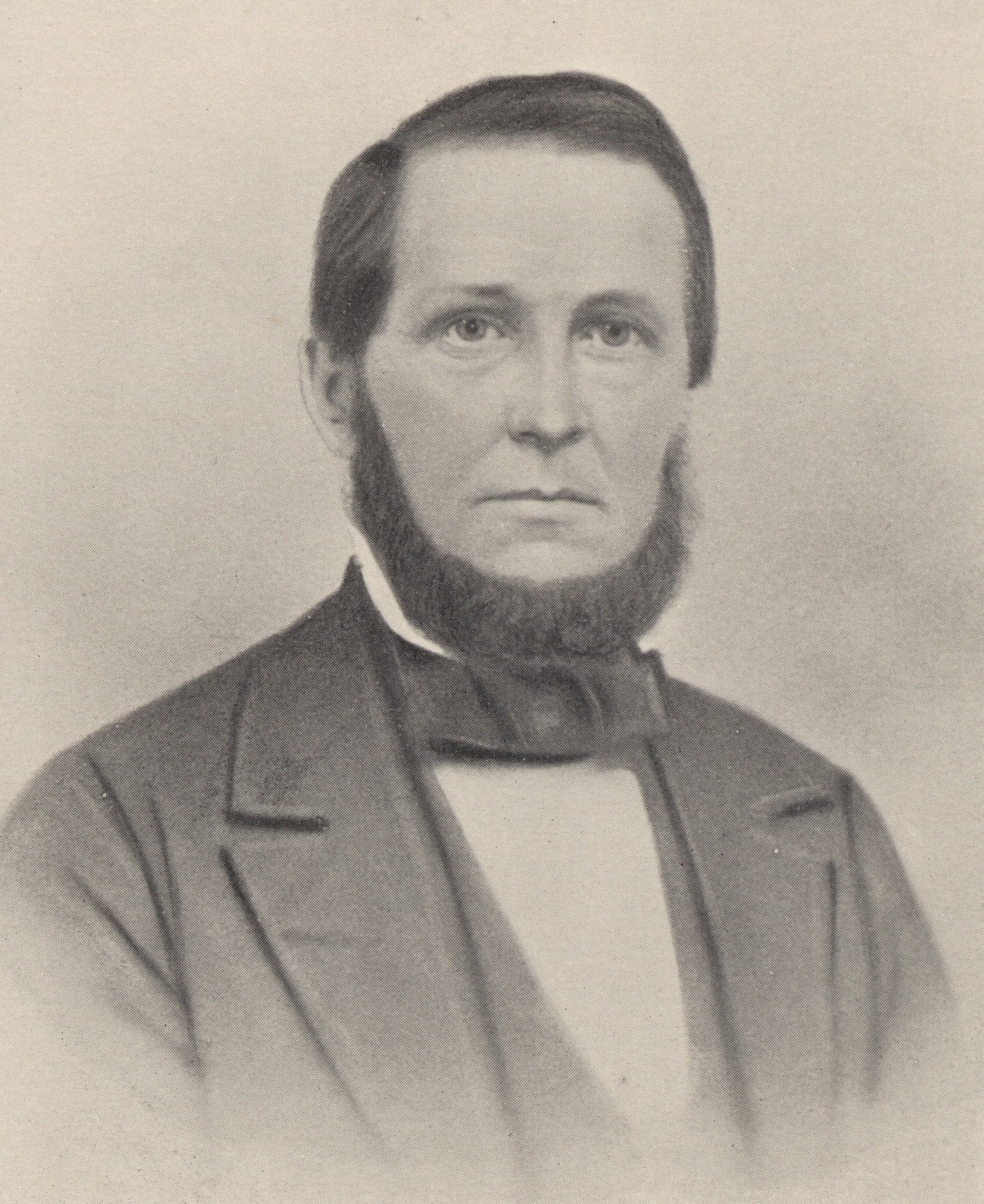

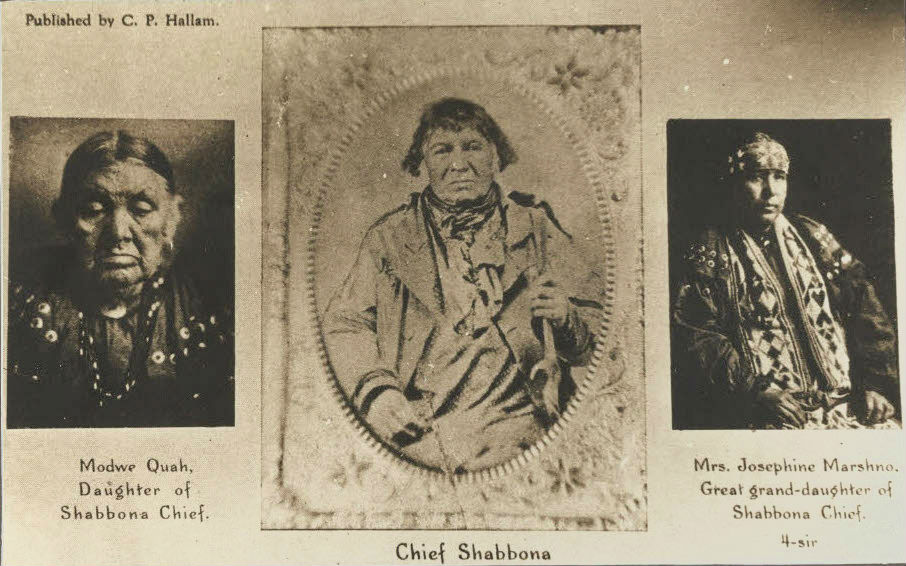

A few weeks ago, we glimpsed the life of the Pottawatomi War Chief Senachwine, who lived with his tribe in Washington Township during the 1820s when settlers began to pour into the future Tazewell County. This week we will take a look at the customs of the Pottawatomi of central Illinois, as they were remembered by pioneer settler Lawson Holland, who knew Senachwine for about 10 years before the chief’s death in the summer of 1831.

Holland’s memories of the Pottawatomi were collected by Charles C. Chapman, who included them in his “History of Tazewell County” (1879), on pages 675-676.

“The peculiar habits of these time-honored natives were naturally a deep curiosity to the whites,” Chapman writes, “and from the well-stored memory of Lawson Holland we were enabled to gather some facts and incidents which we place upon the records of this work, knowing that only a few years could pass ere they would have been lost in the debris of time.”

The first of Holland’s recollections had to do with how the Pottawatomi hunted turtles to eat. Chapman writes, “The preparations incident to this journey are somewhat extended. Two horses are placed side by side, and a blanket stretched between them, and the party start for the streams. The turtles are thrown in this blanket, and when a full load is secured they are carried to the camp, and a large kettle filled with water is placed over the fire, and in the boiling chauldron (sic) the living turtles are thrown, until the kettle is filled. When thoroughly boiled, the meat is plucked from the shell and eaten.”

Holland also recalled a sacrificial tradition, “which has existed among the Pottawatomies for ages, . . . that at a certain time of the year, a deer must be killed and eaten without breaking a single bone. This performance is entered into largely, and the greatest caution taken to secure the animal without a bone being broken. It is then roasted, and the meat eaten with the greatest possible care. The remains are then gathered up, placed in the skin of the animal and buried.”

Holland also observed that the higher status members of the tribe would display their wealth and status with ornamental jewelry and “piercing the nose and ears, from which hang large rings and bells; also bells attached to a strap bound around the leg or ankle.”

Pottawatomi marriage customs, according to Holland, included a clearly delineated division of labor between the two sexes. Chapman writes, “In marriage the women promise to do all the work, such as skinning animals, dressing hides, building tents, and performing all the manual labor, the males only furnishing the necessities of life. The marriage covenant is made by the exchange of corn for a deer’s foot by the parties to be united, and is a time of great solemnity.”

Polygamy was practiced among the Pottawatomi – the online essay “Potawatomi War Chief (1744-1831) Chief Senachwine” says Senachwine reportedly had three wives and could not be persuaded to give up polygamy even after he was baptized as a Christian. The Pottawatomi also punished adultery severely. Chapman writes, “The punishment for adultery is cutting off the nose; the first offense being punishable by a small piece, the second a larger one, and the third cuts it to the bone. These are rare cases, however, both sexes having a high regard for purity and virtue.”

The last Pottawatomi custom that Holland remembered had to do with their burial customs. “In the winter the dead are entombed by standing the body upright, around which is placed poles run in the earth,” Chapman writes.

Besides his memories of Pottawatomi custom, Holland also shared some anecdotes of his family’s interaction with the native inhabitants of the county. One of his recollections was of an occasion when Holland’s wife had boiled water to use for washing. A Pottawatomi woman came into her cabin and either fell or sat in the tub. “Her cries called the braves, who lifted her out and carried her to the wigwam,” Chapman writes.

Another of Holland’s anecdotes was of an occasion of violence between the Pottawatomi and the early settlers. This is how Chapman relates Holland’s recollection:

“One day, when Lawson was a boy, and while the family were at dinner, and a Frenchman, named Louey, who was stopping with them, had finished his meal, lighted his pipe, and was leisurely smoking outside the cabin, a stalwart Indian came down the trail and demanded his pipe, which was refused. The Indian then drew his tomahawk and drove it into his skull. Holland and old man Avery, who was there at the time, rushed from the cabin, and Avery grappled with the redskin. He sounded the war-whoop, and in a twinkling the little band of whites were surrounded by hundreds of the swarthy tribe. The Chief [Senachwine], taking in the situation, drew his war-club and struck at Avery with this deadly weapon, but Avery’s quick eye dodged the blow, and the instrument was buried in a large tree behind him. It was a perilous moment and there seemed to be no earthly escape for this little band of pioneers, but [Lawson’s father] was regarded as a friend, and his counsel was at all times sought. The Indians then had a war-dance, and returned to their camps, and peace and quietness was again restored. This occurred in 1822.”