“To rescue a name worthy to be remembered and honoured

To recall great events,

To look back upon the deeds of those gone before us,

Are objects worthy of all consideration.”

— U.S. Secretary of State and Illinois historian E. B. Washburne, 1882

It’s not every day that historical researchers discover new facts that solve long-standing mysteries – but today is one of those days.

Several times in recent years, “From the History Room” has had the opportunity to tell of the life and family of one of Pekin’s most notable historical figures – Nance Legins-Costley, remembered as the first African-American slave freed by Abraham Lincoln. Most of what we know of Nance is the fruit of the research of local historian Carl Adams. Only two weeks ago we took another look at the lives of Nance and her son Private William Henry Costley.

Following close upon the heels of that column, we now return once more to the subject of Nance in order to announce that the answer has been found to the three-fold question, “When and where did Nance die and where was she buried?”

We previously addressed that question here in Aug. 2015. At that time we noted the speculation of late Pekin historian Fred Soady, who thought Nance died circa 1873 in Pekin and had probably been buried in the old City Cemetery that formerly existed at the southwest corner of Koch and South Second streets. We also considered a May 29, 1885 Minnesota State Census record of “Nancy Cosley,” identified in the record as age 72, black, born in Maryland, and living in Minneapolis with James Cosley, 32, born in Illinois. This record is a perfect match for Pekin’s Nance Costley and her son James Willis Costley, especially considering that Nance’s son William was then living in Minneapolis and died three years later in Rochester, Minn.

Lacking any further information, I wondered if Nance may have died in Minneapolis and was buried there or nearby.

We now know the answer to that question is, “No.” Although the 1885 census record shows Nance in Minneapolis, she later returned to central Illinois (presumably after her son William’s death in Rochester in 1888). A few years later, Nance died and was buried in Peoria.

Those facts were discovered by Debra Clendenen of Pekin, a retired Pekin Hospital registered nurse and local genealogical researcher who has been engaged in a project of creating Find-A-Grave memorials for deceased individuals whose names are recorded in the old Peoria County undertakers’ records.

While engaged in that project, Clendenen came across the burial records of Nance Legins-Costley, her husband Benjamin Costley, their son Leander “Dote” Costley, their daughter and son-in-law Amanda and Edward W. Lewis, and Amanda’s and Edward’s sons Edward W., William Henry, Ambrose E., Jesse, and John Thomas. Clendenen has created Find-A-Grave memorials for all of those members of Nance’s family. She added Benjamin’s memorial on March 8 this year, and then added Nance’s memorial on March 12.

Clendenen described her discoveries earlier this month in an email dated June 6, 2019:

“The heroes of this tale are the undertakers who kept such remarkably detailed records and the Peoria County Clerks who have housed their records for nearly 150 years.

“The records began in 1872 and were discovered in the basement of the Peoria Courthouse a few years ago by Bob Hoffer of Peoria. He photographed the records and gave them to the Peoria County Genealogical Society who transcribed and published them.

“I have been photocopying pages of the books at the Tazewell County Genealogical & Historical Society in Pekin and creating Find-A-Grave memorials from them. I am ‘blessed’ with an enormous curiosity gene. I use Ancestry.com to research the folks I create memorials for. I have created 35,000 memorials over an eight-year period.

“So that is the journey Nance’s burial took from the undertaker to my hands.”

The Peoria County undertaker’s report for Nance says she was born in Maryland and died of old age at the remarkable age of 104, on April 6, 1892. The report lists her residence at 226 N. Adams St., which means she was living with her daughter Amanda and son-in-law Edward. According to the report, Nance was buried in Moffatt Cemetery in Peoria.

Her husband Ben had died nine years earlier. His undertaker’s report says he died at the age of 86 on Dec. 4, 1883, with the cause of death listed as unspecified “injuries.” His residence was 517 Hale St., and he was, according to the report, buried in Springdale Cemetery.

Clendenen has expressed doubt about whether or not Benjamin and Nance were really buried in different cemeteries. The undertaker’s reports for their children Amanda and Leander are similar, showing Amanda buried in Springdale and Leander buried in Moffatt. Even though Benjamin is said to have been buried in Springdale, Springdale Cemetery has no record of his burial, so Clendenen thinks it is possible he may have really been buried in Moffatt Cemetery.

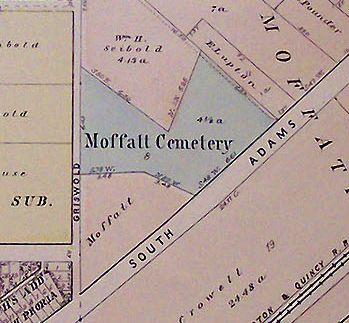

Moffatt Cemetery, at 3900 S.W. Adams St. (the corner of Adams and Griswold), was one of Peoria’s oldest cemeteries, starting as early as 1836 as a burying ground for the family of Peoria pioneer Aquila Moffatt (1802-1880). The cemetery has long been defunct, however, being officially closed in 1905 after burial space ran out. Eventually the cemetery sank into decrepitude and neglect, overgrown and the gravestones crumbling and fallen. As Bob Hoffer discovered in his research, the Peoria City Council finally voted in 1954 to rezone the property as light industrial, after which it appears that most of the burials were relocated – but many burials are probably still there, at the site that is now the location of a roofers union office, muffler shop, an electrician, and a parking lot. (See the story of Hoffer’s research efforts in “Peoria searching for Civil War grave finds forgotten cemetery,” in the May 27, 2017 edition of the Peoria Journal Star)

Although study of the Peoria County undertaker’s reports for Benjamin and Nance Costley has at last revealed when and where Nance and her husband Ben died, their reports do raise some questions. First of all, in both Nance’s and Ben’s reports their stated ages at death are obviously erroneous. Earlier U.S. and state census records indicate that Nance was born circa 1813 while Ben was born circa 1811 or 1812. In fact even those earlier census records give varying ages. Knowing that Nance and Ben were illiterate, and that Nance had been born in slavery, most likely they themselves were unsure of when they were born.

Carl Adams, leading expert on Nance’s life, has identified Nance as a daughter of the slaves Randall and Anachy Legins, who are known to have had a daughter in Kaskaskia, Illinois, in December 1813 – this matches Nance’s age from the census records, and thus we can narrow down Nance’s birth to that month and year. Their owner Nathan Cromwell was born in Maryland. Nance may have appropriated that as her place of birth, either because she was confused or because, given the grave injustices that Illinoisans had inflicted upon her in her younger days, she disavowed the place of her birth. Or, as Adams suspects, it may have been a census-taker’s error, attributing to the slaves the place of the birth of their master. Be that as it may, Nance was 78 when she died, not 104. Nance’s daughter Amanda was likely the one who supplied the undertaker with her mother’s age, and Amanda herself likely did not know how old her mother really was. Unfortunately we’ll never know how Nance’s age came to be inflated from 78 to 104. As for Nance’s husband Ben, based on census records he probably died at the age of 70 or 71, not 86.

There is still doubt regarding the disposition of the burials that were removed from Moffatt Cemetery. Were they moved to another cemetery, and if so which one? Were the remains of Nance and Leander among those that were removed, or are they still in situ, covered over by a parking lot? There’s no way to be sure at this time.

Even so, with Clendenen’s discovery of the undertaker’s reports for Nance and her family, and her creation of online memorials for them at Find-A-Grave, we can finally write the final chapter of Nance’s remarkable life. Memory eternal!