This is a revised version of a “From the Local History Room” column that first appeared in March 2012 before the launch of this weblog, republished here as a part of our Illinois Bicentennial Series on early Illinois history.

Last month Pekin and nearby communities commemorated the 100th anniversary of one of the most tragic events seared into Pekin’s collective memory: the Columbia riverboat disaster. On July 5, 1918, the steamboat Columbia sank on the Illinois River four miles north of Pekin when it struck a submerged tree stump, ripping a gaping hole in the hull. Out of 496 passengers, 87 died, including 57 Pekin residents.

It was the last large scale river disaster in our area – but steamboats had been plying the waters of the Illinois River since about 1829, when the steamer Liberty visited Peoria, so it should be no surprise that the wreck of the Columbia wasn’t Pekin’s first steamboat disaster. On July 12, 1892, the excursion steamer Frankie Folsom capsized during a storm on Peoria Lake while bringing passengers back to Pekin from Peoria. Most passengers escaped, but 11 died.

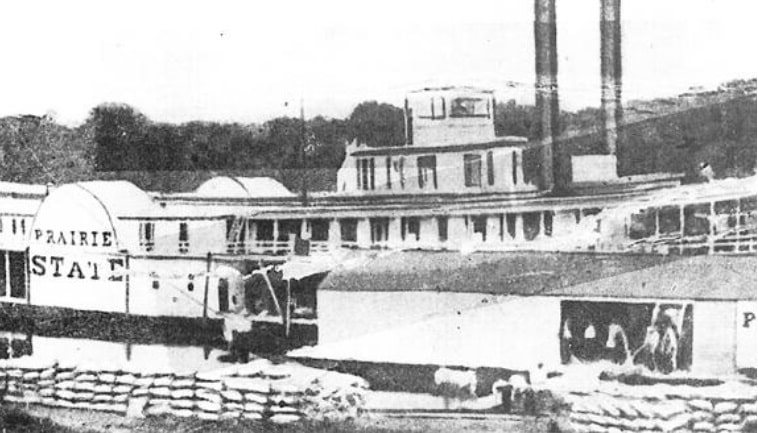

Pekin’s first steamboat disaster was on April 25, 1852, when the boilers of the Prairie State exploded, allegedly killing more than 100 passengers.

The story of this tragedy is told and retold in several of the standard works on Pekin’s history, but, surprisingly, none of those works gives the correct date of the disaster. Ben C. Allensworth’s 1905 History of Tazewell County, the 1949 Pekin Centenary, and the 1974 Pekin Sesquicentennial each claim that the Prairie State exploded on Sunday morning, April 16, 1852. The problem with that date is that April 16 was a Friday that year.

“Pekin: A Pictorial History” (2004) gets closer to the truth, placing the tragedy on Sunday morning, April 24, 1852. However, that day was a Saturday. The correct date is found in “Lloyd’s Steamboat Disasters” (1856), page 293, which says, “The steamer Prairie State collapsed her flues on the Illinois River, April 25th, 1852, killing and wounding twenty persons.” That date was, as Pekin’s history book states, a Sunday.

The number of dead reportedly was far more than 20. “Pekin: A Pictorial History,” page 176, tells the story in these words:

“. . . [T]the packet steamers, Prairie State and Avalanche, southward bound, landed almost simultaneously at the Pekin Wharf and collided. Both were carrying a high head of steam. As a result the boilers on the Prairie State exploded with terrific force. ‘It was the church going hour, but the worship of the Deity was changed to the duties of the Good Samaritan,’ according to Cole’s Guide. The 110 bodies that were recovered were placed side by side under the walnut and oak trees on the bank and every home in the vicinity became a temporary hospital. One rescued passenger, en route to Texas, reported that many of the victims he had seen on board were not recovered. A final count of those who drowned was never ascertained.”

That account repeats most of details and uses much of the same language of Allensworth’s 1905 recollection:

“The two steamers, the ‘Prairie State’ and the ‘Avalanche’ coming from the north, landed almost simultaneously at the Pekin wharf. They were evidently racing as both were carrying a high pressure of steam. The ‘Prairie State’ pulled out of the landing ahead of her competitor, and when nearly opposite our gas works, her boilers exploded with terrific force. This happened on Sunday about the time for the beginning of church services. The people went to the rescue of the injured, and the wreck of the ‘Prairie State’ was towed back to the wharf by the ‘Avalanche.’ Many bodies were recovered and laid side by side under the walnut and oak trees on the bank of the river. The citizens turned their houses into temporary hospitals in which the injured were cared for.

“Mr. James Sallee was a passenger going to Texas, and is authority for the statement that the boat was crowded with passengers, many of whose bodies were never recovered.”

The 1974 Sesquicentennial also more specifically locates the Prairie State’s explosion at “a point nearly opposite ‘gas house hill’ (in the area of 100 Fayette Street).”

The 1949 Centenary and the Sesquicentennial also repeat Allensworth’s account and recycle some of his words. The Centenary added the darkly humorous observation that, “Pekin’s population increased by a somewhat unusual method, when a large number of people literally ‘blew into town,’” explaining that many of the survivors decided to stay on in Pekin after their recovery.

One of the survivors, according to the Centenary, was “the grandfather of Paul Sallee, the present Pekin trouper,” who is called “a well-known area entertainer” in the Sesquicentennial. Paul Sallee’s grandfather, of course, was the James Sallee of Allensworth’s account.