This is a revised version of a “From the Local History Room” column that first appeared in February 2015 before the launch of this weblog, republished here as a part of our Illinois Bicentennial Series on early Illinois history.

Last week we surveyed the history of the pre-Civil War slavery abolition movement in Pekin, spotlighting local abolitionists such as Dr. Daniel Cheever of Pekin and the Woodrow brothers, Samuel and Hugh.

As we saw previously, Cheever engaged in Underground Railroad activities from his home at the corner of Capitol and Court streets, (and whose farm near Delavan was a depot on the Underground Railroad, by which runaway slaves were helped to escape to freedom and safety in Canada. At the same time, the Woodrow brothers were early Pekin settlers (Catherine Street was named for Samuel’s wife and Amanda Street was named for Hugh’s) who later lived in Circleville south of Pekin, where they aided runaway slaves at their homes.

In his 1879 “History of Tazewell County,” Charles C. Chapman devotes an entire chapter of his book – chapter IX – to the running of the Underground Railroad in Tazewell County, on which the “freight” were human beings. As Chapman explains, abolitionists in Illinois frequently encountered fierce and violent opposition from pro-slavery settlers.

Those whose moral convictions spurred them to assist runaway slaves also risked punishment, since both federal and state law prescribed stiff penalties not only for anyone who helped a runaway slave gain his freedom but also for anyone who refused to help recapture runaways.

“Pro-slavery men complained bitterly of the violation of the law by their abolition neighbors, and persecuted them as much as they dared: and this was not a little. But the friends of the slaves were not to be deterred by persecution,” Chapman writes.

Here are some of Chapman’s stories of Tazewell County’s Underground Railroad, from pages 317-319 of his history:

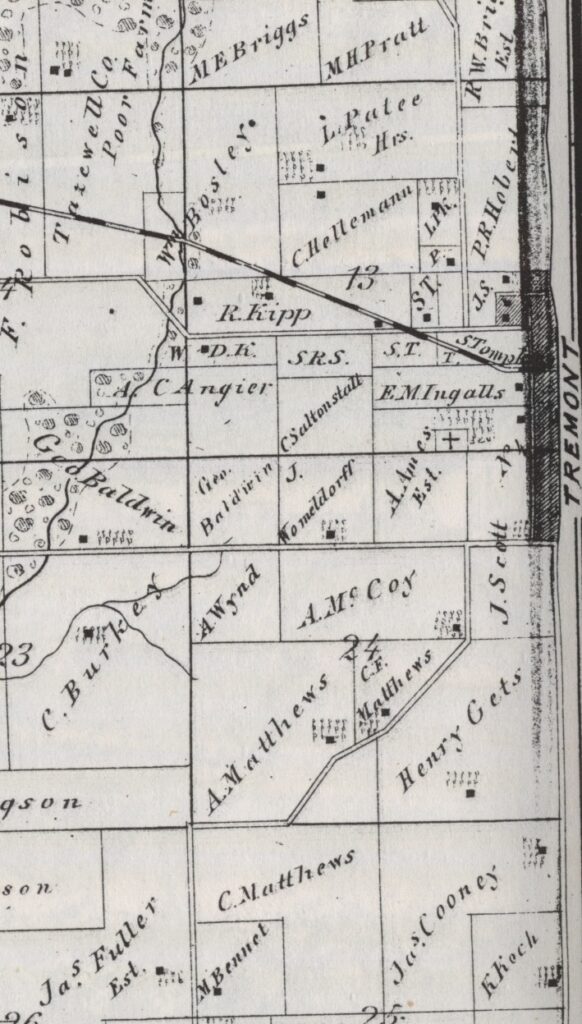

“The main depot of the U. G. Road in Elm Grove township was at Josiah Matthews’, on section 24. Mr. Matthews was an earnest anti-slavery man, and helped to gain freedom for many slaves. He prepared himself with a covered wagon especially to carry black freight from his station on to the next. On one occasion there were three negroes to be conveyed from his station to the next, but they were so closely watched that some time elapsed before they could contrive to take them in safety. At last a happy plan was conceived, and one which proved successful. Their faces were well whitened with flour, and with a son of Mr. Matthews’ went into the timber coon-hunting. In this way they managed to throw their suspicious neighbors off their guard, and the black freight was safely conducted northward.

“One day there arrived a box of freight at Mr. Matthews’, and was hurriedly consigned to the cellar. On the freight contained in this box there was a reward of $1,500 offered, and the pursuers were but half an hour behind. The wagon in which the box containing the negro was brought was immediately taken apart and hid under the barn. The horses, which had been driven very hard, were rubbed off, and thus all indications of a late arrival were covered up. The pursuers came up in hot haste, and, suspecting that Mr. Matthews’ house contained the fugitive, gave the place a very thorough search, but failed to look into the innocent-looking box in the cellar. Thus, by such stratagem, the slave-hunters were foiled and the fugitive saved. The house was so closely watched, however, that Conductor Matthews had to keep the negro a week before he could carry him further. This station was watched so closely at times that Mr. Matthews came near being caught, in which case, in all probability, his life would have been very short.

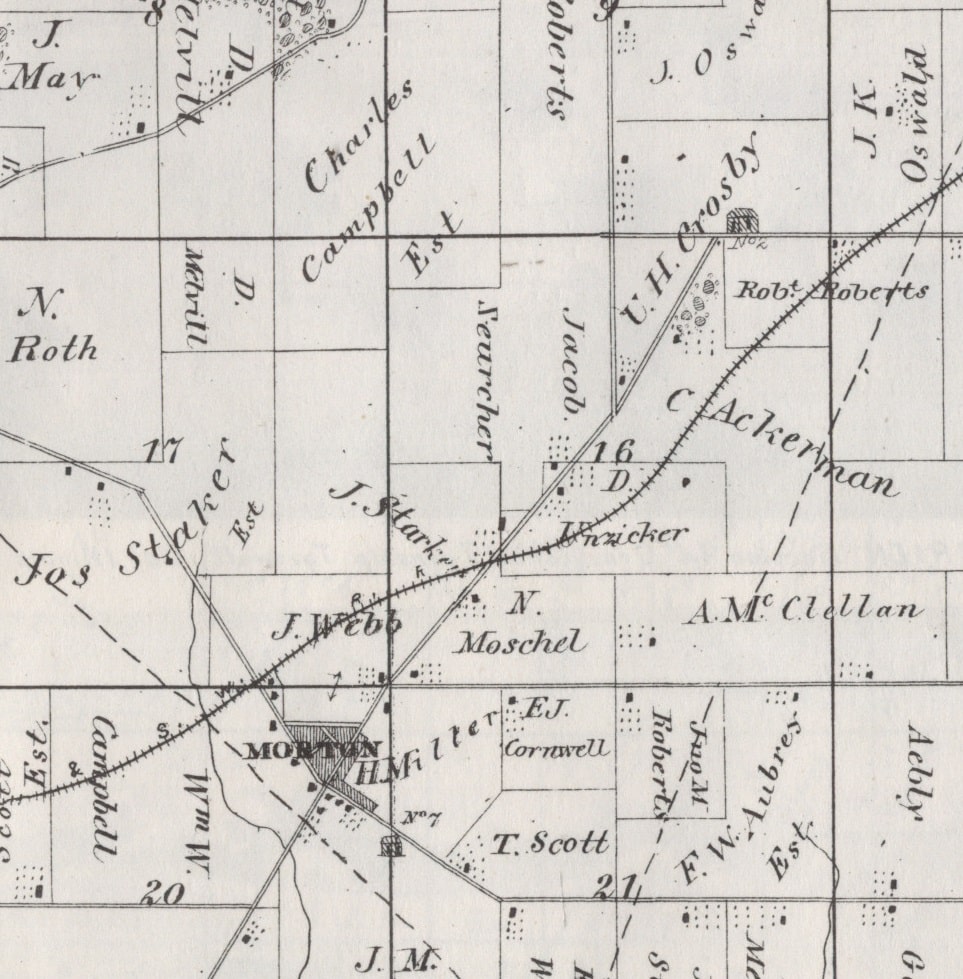

“Mr. Uriah H. Crosby, of Morton township, was an agent and conductor of the U.G.R.R., and had a station at his house. On one occasion there was landed at his station by the conductor just south of him, a very weighty couple, — a Methodist minister and wife. They had a Bible and hymn book that they might conduct religious exercises where they found an opportunity along the way. On conducting them northward Mr. Crosby was obliged to furnish each of them an entire seat, as either of them were of such size as to well fill a seat in his wagon. The next station beyond was at Mr. Kern’s, nine miles. He arrived there in safety, and his heavy cargo was transported on to free soil — Canada.

“The next passenger along the route that stopped at Crosby station arrived on election day. A company had passed on northward when a young man hastily came up. He had invented a cotton gin, and was in haste to overtake the others of the party as they had the model of his invention. He was separated from them by fright. J. M. Roberts found this young man in the morning hid away in his hay-stack, fed him, and sent his son, Junius, with him in haste to Mr. Crosby’s. On his arrival Conductor Crosby put him in his wagon, covered him with a buffalo robe, and drove through Washington and delivered him to Mr. Kern, who took him in an open buggy to the Quaker settlement. He overtook his companions.

“One of the saddest accidents that ever occurred on the U.G. Road in Tazewell county was the capture of a train by slave hunters. Two men, a woman and three children, were traveling together. The woman and children could journey together only from Tremont toward Crosby station, as they had only one buggy. The negro men concluded to walk, but stopped on the way to rest. Waiting as long as they dared for the men to come up, Messrs. Roberts started on with the women and children, but had not gone far before they were stopped by some slave hunters and their load taken from them. The mother and her three children, who were seeking their liberty, were taken to St. Louis and sold, as the slave hunters could realize more by selling them than by returning them to the owner and receiving the reward.

“When the two men came up it was thought best to take them on by a different route, the people determining they should not be captured. J. M. Roberts arranged to take them on horseback to Peoria lake. Several men accompanied them, riding out as far into the water as they could, and by a preconcerted signal parties brought a skiff to them, into which the men were taken and conveyed across the river and sent on the Farmington route in safety. All other routes were too closely watched.”