In looking back over more than two centuries of history in Illinois, numerous instances can be found in which religious faith – and in particular, Christianity – has motivated Illinoisans to try to make positive changes in the world.

Among the most notable examples are the social progress movements of the 19th and 20th centuries, such as the drive to abolish slavery, as well as efforts to alleviate the plight of the poor and improve working conditions, to establish schools, to provide care for the sick, and to right the wrongs of social inequity and injustice. Even the Alcohol Prohibition movement, now generally held to have been wrongheaded, arose from the desire of Methodist and Baptist Protestants to address serious social evils associated with the abuse of alcohol.

Despite the many positive contributions of religious faith, there has also been a dark side to religion, and that holds true in Illinois history as well. This week we turn our attention to one of the blackest episodes in Illinois’ early history: an eruption of religious controversy and persecution that culminated in the violence of the Mormon War of 1844-1846.

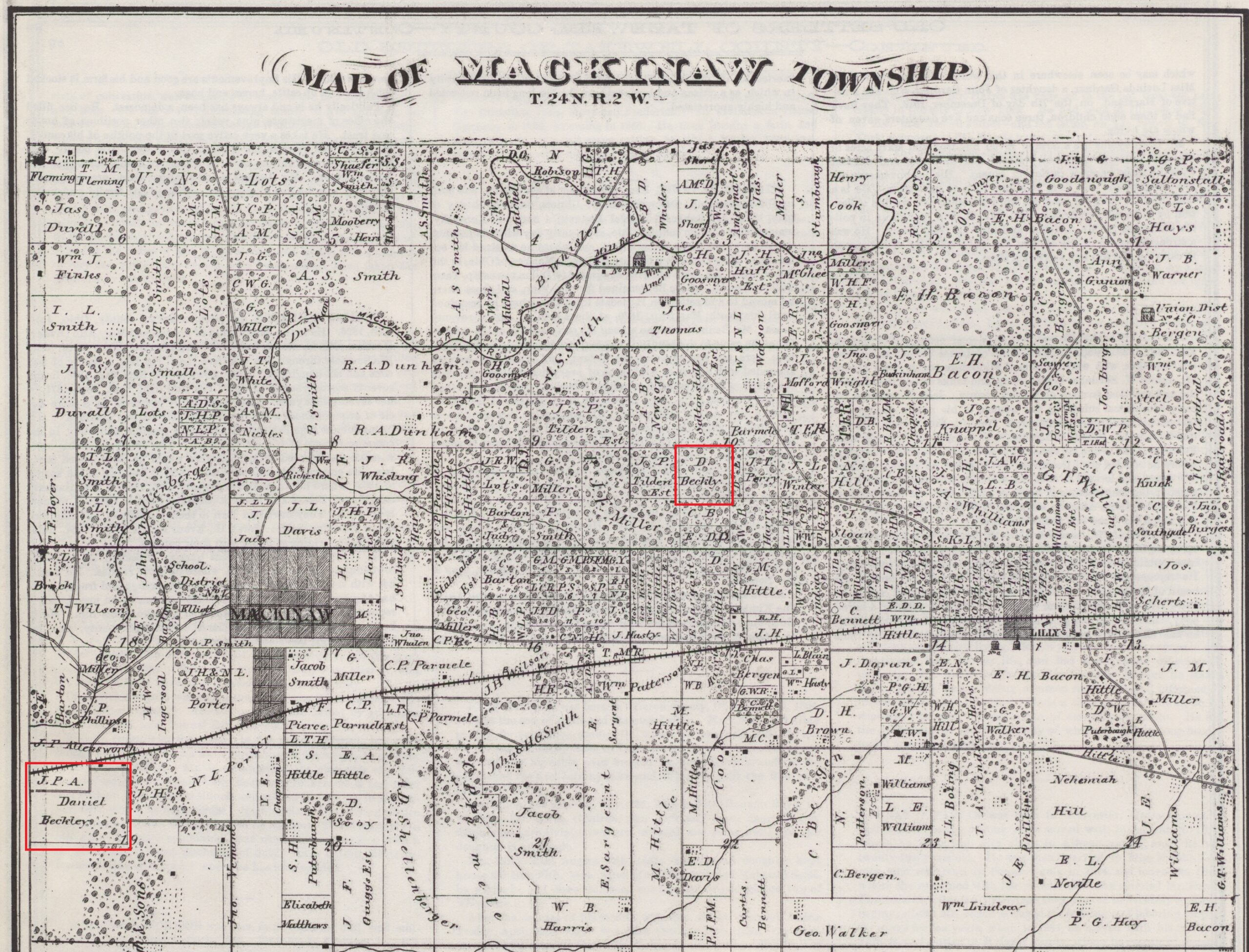

To understand how it happened that a religious war broke out among Illinois’ pioneer settlers, first one must review the life of Joseph Smith (1805-1844), founding prophet of the Mormon church. One possible resource (perhaps surprisingly) in the Local History Room is Charles C. Chapman’s 1879 “History of Tazewell County.” Though Tazewell County was not the location of the Mormon War, nor was our county directly involved in it, the first part of Chapman’s book is a general history of Illinois that includes a 14-page account of the Mormon controversy and the Mormon War (pages 104-118). Chapman’s account has an anti-Mormon point of view, but is also critical of the Mormons’ enemies.

Chapman’s account begins with the origins of the Mormon religion in western New York in the late 1820s, during a time of unusual religious enthusiasm in America known as the Second Great Awakening. Properly known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, among non-Mormons the religion is commonly known as “Mormonism” and its followers called “Mormons” – so named from their own sacred scriptures, the Book of Mormon (first published in 1830), that for the Latter-day Saints is a companion or supplement to the Protestant Christian Bible. Joseph Smith claimed to have translated the book from golden plates inscribed with a form of the Egyptian language. According to Smith, an angel named Moroni had revealed the golden plates to him in 1823, and the transcription and translation of the plates was completed in 1829.

On April 6, 1830, in Palmyra, N.Y., Smith and his followers formally organized themselves as “the Church of Christ,” preaching that God had chosen them to restore and purify Christianity, which, they said, had lost the true teachings of Jesus Christ. Almost immediately Smith and his church encountered opposition and resistance from orthodox Christians and others who believed Smith was a charlatan. With a real threat of mob violence looming, later in 1830 Smith pronounced a revelation that he and his New York followers should relocate to Kirtland, Ohio, to join Sidney Rigdon’s group of Mormon converts there.

For most of the years from Jan. 1831 to Jan. 1838, Smith presided over his church from his headquarters in Kirtland. Meanwhile, Smith’s associate Oliver Cowdery, whom he had sent west to find the right location for the establishment of “New Jerusalem” on earth, informed the church that God had chosen Jackson County, Mo., as the site of the New Jerusalem. After seeing the area in person in July 1831, Smith agreed, declaring that Zion’s “center place” was Independence, Mo. Thus, throughout the 1830s the church had two main branches, one in Ohio and the other in Missouri.

Alarmed by the influx of Mormon converts moving into Kirtland, in early 1832 a mob of Ohioans attacked Smith and Rigdon, tarring and feathering them and nearly beating them to death. Afterwards, Smith moved to Missouri for a while and developed the church organization there. The Mormon newcomers in Missouri frequently suffered violent opposition, so the Missouri Mormons began to use force to defend themselves. This led to a clash in July 1833 between armed bands in which a Mormon and two non-Mormons were killed, and the non-Mormons then drove all the Mormons out of Jackson County.

In Kirtland, Ohio, Smith’s authority in the church was challenged in late 1837 when Cowdery publicly accused him of carrying on a sexual affair with his serving girl Fanny Alger. Smith and his church also faced financial scandals due to lingering debts from the building of the Kirtland Temple and the collapse of a church-sponsored bank that Smith had encouraged his followers to invest in. In Jan. 1838, a warrant was issued for Smith’s arrest on charges of bank fraud. Smith and Rigdon then left Kirtland and moved to Missouri.

In Missouri, Smith consolidated his authority over the church, which he renamed the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. At this time, the church excommunicated Cowdery and several other of the church’s early leaders. At the same time animosity between the Mormons and non-Mormons and ex-Mormons grew even more fierce. This animosity broke out in open hostilities during the Mormon War of 1838, in which non- and ex-Mormons and Mormons attacked and burned each other’s farms and towns.

At the Battle of Crooked River on Oct. 24, 1838, the forces of the Latter-day Saints attacked the Missouri State Militia, which they had mistaken for a band of anti-Mormon vigilantes. This led Missouri Gov. Lilburn Boggs to issue an executive order directing that all Mormons be “exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public peace.” A few days later, a group of state militiamen massacred 17 Mormons at Haun’s Mill in Caldwell County. With the church facing expulsion, Brigham Young (1801-1877), president of the church’s Quorum of Twelve Apostles (and later to become the church’s second president in succession to Smith), organized the relocation of Mormon refugees to Illinois and Iowa. Smith, Rigdon, and other Mormons were arrested and charged with treason, but on April 6, 1839, they escaped from jail and fled to Illinois.

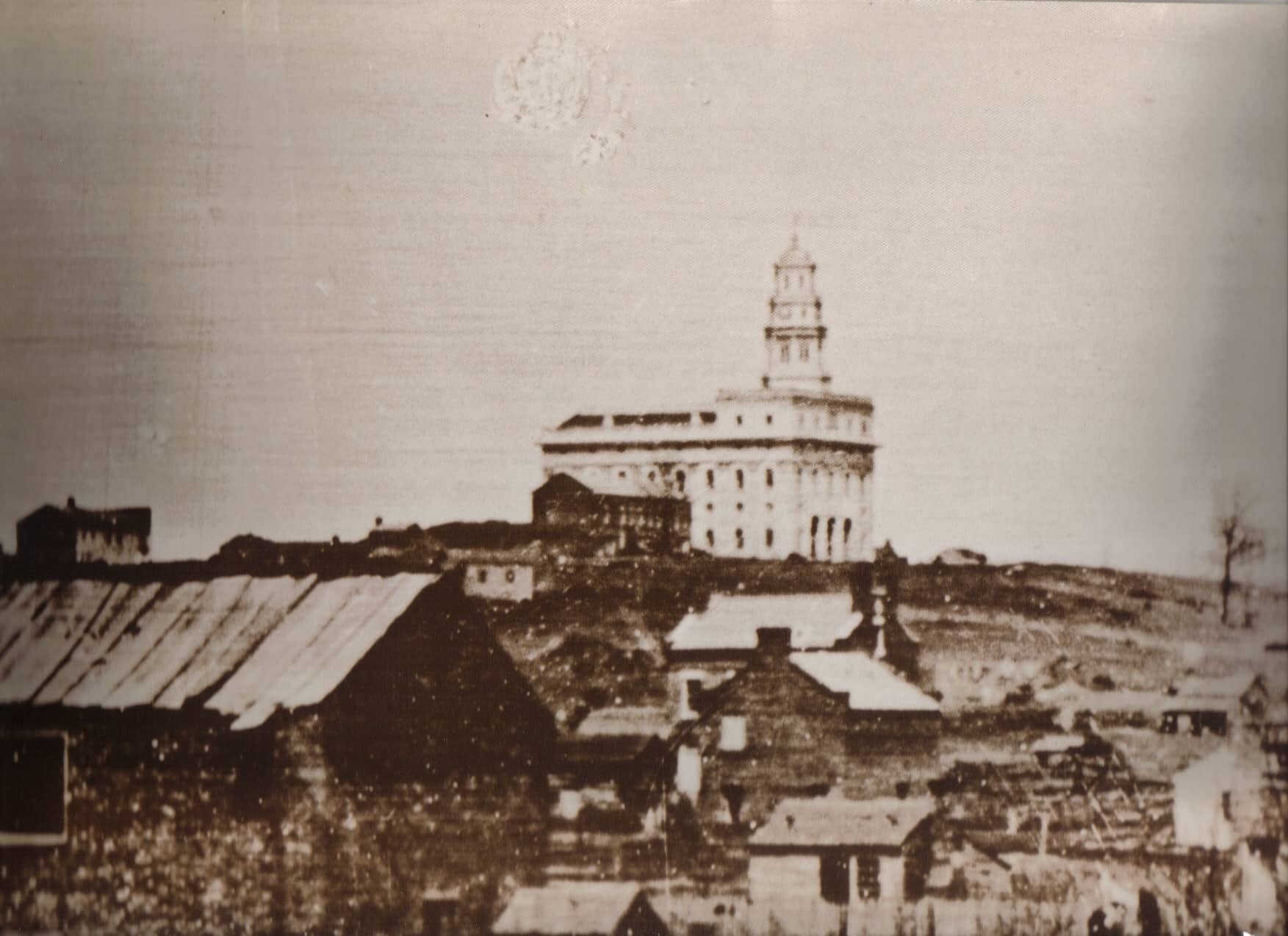

Before long, much the same story that had played out in Ohio and Missouri repeated itself in Illinois. Smith established his headquarters at Commerce, a town on the Mississippi River in Hancock County. In April 1840, Smith renamed the town “Nauvoo,” from the Hebrew word nawu (“beautiful”) from Isaiah 52:7. Nauvoo was granted a city charter on Dec. 16, 1840, which took effect Feb. 1, 1841, making Nauvoo the sixth incorporated city in Illinois. The city’s first mayor was a prominent Mormon convert named John C. Bennett, quartermaster general of the Illinois State Militia. Bennett and Smith together headed the Nauvoo Legion, an autonomous corps of 2,000 state militia riflemen. By 1844, Nauvoo had 12,000 inhabitants – the second largest city in Illinois.

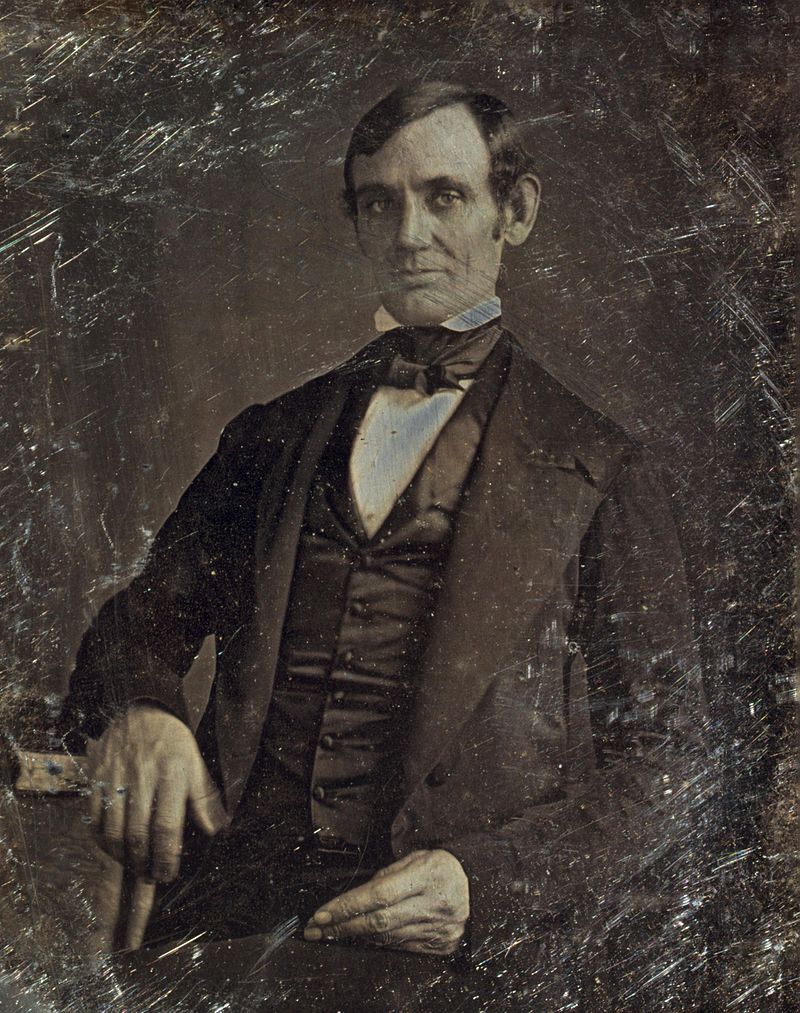

Though Illinoisans at first were sympathetic to the Mormon refugees’ plight, many non-Mormons near Nauvoo soon began to view the growing political power of Smith and his followers as a threat. Smith’s supreme status in his church made him effectively immune to Missouri’s attempts to extradite him on treason charges, and enabled him to mobilize his followers as the deciding voting bloc in a state in which the Democrat and Whig parties were equal in strength. The Mormon bloc thus decided elections by voting for candidates as directed by the church’s leaders.

During Smith’s time in Nauvoo, he introduced new teachings and practices, including the practice of proxy baptism (“baptism for the dead”) – the belief that motivates Latter-day Saints to conduct extensive genealogical research (for which the Mormons are best known today). Smith also espoused a theocratic political ideology which he called theodemocracy, and he began to have political ambitions of his own. In Dec. 1843, Smith petitioned Congress to have Nauvoo made an independent territory, but the petition was ignored. Then, on Jan. 29, 1844, Smith announced he was running as an independent for President of the United States of America.

Most scandalous, however, and perhaps the main thing that turned non-Mormons against the Latter-day Saints, was Smith’s doctrine of polygamy, which he introduced to some of the church’s leading men in 1841. (The Latter-day Saints officially renounced polygamy in 1890.) When Nauvoo Mayor Bennett was caught in adultery, he claimed Smith approved of “spiritual wifery” (as Bennett called it) and practiced it himself. Due to the scandal, Bennett was expelled from Nauvoo in the summer of 1842, and Smith himself then took the reins as Nauvoo’s mayor.

In the spring of 1844, just a few months into Smith’s presidential campaign, the Mormon church suffered a schism over the doctrine of polygamy. Several of Smith’s close associates broke away and organized what they called the True Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The breakaway group was headed by William Law, who along with Robert Foster accused Smith of proposing marriage with their wives. Law and his colleagues founded an anti-Mormon paper, the Nauvoo Expositor, in which they vehemently denounced Smith as a “fallen prophet,” condemning his theology as polytheistic, and calling for the revocation of Nauvoo’s city charter.

In reaction, the Nauvoo city council, acting with Smith’s agreement, declared the Expositor to be a “public nuisance,” ordering the Nauvoo Legion to destroy the paper’s press – an unconstitutional act beyond the authority of the mayor and council of Nauvoo. The Legion executed the order on June 10, 1844, also destroying all copies of the newspaper they could find. This action caused so great an uproar in the area that Smith declared martial law on June 18 and mobilized the Nauvoo Legion. In answer, officials in Carthage mobilized their detachment of the state militia, and Illinois Gov. Thomas Ford came from Springfield, saying he would raise an even larger militia unless Smith and the Nauvoo city council surrendered on charges of inciting a riot.

Smith briefly fled to Missouri (where he was still wanted for treason), but soon returned and on June 23, with his brother Hyrum, surrendered to Gov. Ford at Carthage on treason charges. Four days later, an armed mob of about 200 men attacked the Carthage Jail. Hyrum Smith was shot and killed almost instantly, while Joseph Smith, defending himself with a pistol that his follower Cyrus Wheelock had previously smuggled into the jail, managed to wound three of his assailants before being struck by several gunshots and then fell from a second-storey window to the ground, where his murderers shot him several more times as he lay dying. Five men were charged with his murder, but all were acquitted.

Anti-Mormon sentiment grew even more inflamed after Smith’s assassination, leading to the outbreak of the Mormon War in Illinois in October 1844. The “war” consisted of an active campaign of harassment and violence intended to pressure the Mormons to leave Illinois. It began with an illegal gathering of anti-Mormon residents of Carthage and Warsaw, who plotted to hunt down and murder or drive all the Mormons out of Hancock County or Illinois. Gov. Ford sent a militia to disperse the anti-Mormons, but many of his militiamen instead joined the anti-Mormons’ “wolf hunt.” Mormons in the countryside fled for protection to Nauvoo, whose city charter was revoked by the Illinois General Assembly on Jan. 29, 1845, one year to the day after Smith had launched his presidential campaign.

From 1844 to 1846, vigilante anti-Mormons in the area continued to harass the Mormons and to agitate for their expulsion from the state, burning the homes and farms of the Mormons, who counterattacked and burned anti-Mormon farms in retaliation. Consequently, in the winter of 1845-46 the Mormons, under Brigham Young’s leadership, resolved to leave Illinois and set to work on plans to seek a safe haven in western regions of the U.S., led along the Mormon Trail and other routes to Utah. The majority of Nauvoo’s Mormons had left Illinois en masse by the spring of 1846. The Mormon War concluded with the so-called Battle of Nauvoo, in which a force of 1,000 anti-Mormons besieged the town’s remnant of defenders on Sept. 10, 1846. After about a week of fighting, the Mormons surrendered on Sept. 16 and agreed to be deported to Missouri.

Thus ended the so-called Mormon War, in which the “frontier justice” of Illinois’ pioneer days frequently mutated into frontier injustice.

In the aftermath of the Mormon Exodus, as it is called, the Mormons’ abandoned temple in Nauvoo was destroyed by arsonists in 1848. By the early 1900s, Nauvoo had become a small city with a majority Catholic population. In recent times, however, the Latter-day Saints reestablished a presence in Nauvoo, rebuilding and rededicating their Temple in 2002.