This is a revised version of a “From the Local History Room” column that first appeared in May 2015 before the launch of this weblog, republished here as a part of our Illinois Bicentennial Series on early Illinois history.

This week we’ll take a closer look at the form and expression of religious faith during Pekin’s earliest times, spotlighting the origin of Pekin’s first Methodist Christians.

While the first European settlers to come to Tazewell County were Catholic Christians, following the establishment in 1824 of the settlement that would become Pekin, Methodism was the first religion to formally establish its presence among Pekin’s pioneer settlers. Pekin’s “first family,” the Tharps, had become Methodists before leaving Ohio for Illinois. As we have noted before, Pekin’s first preaching service took place in 1826, when Jacob Tharp invited Rev. Jesse Walker, a Methodist circuit-rider, to preach in Tharp’s log cabin.

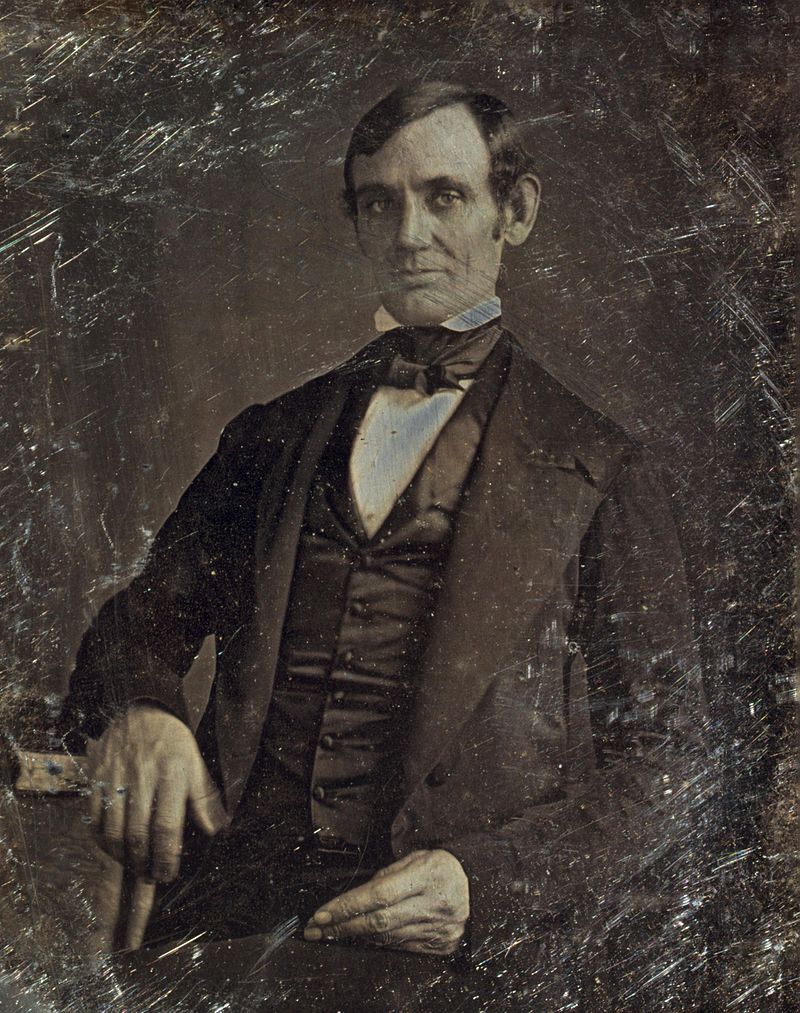

In his 1879 “History of Tazewell County,” pages 580-594, Charles C. Chapman provides an account of the history and progress of religion in Pekin, beginning with Rev. Walker’s preaching service. After Walker, a certain Rev. Lord ministered to Pekin’s first settlers. It was in 1827 that the first Methodist society, consisting of about eight or 10 members, was formed in Pekin by Smith L. Robinson. After Lord, Rev. John Sinclair arrived in 1831. Sinclair and Rev. Zadock Hall formally organized a Methodist Episcopal Church in Pekin, and Hall in turn was succeeded in 1834 by the church’s first regular installed minister, Rev. John Thomas Mitchell (1810-1863), a 24-year-old deacon who was active throughout northern and central Illinois.

The following excerpts from Chapman’s account provide some colorful anecdotes from Mitchell’s time as Pekin’s Methodist minister.

“The Rev. John T. Mitchell followed Rev. Hall. He was a man of great power and eloquence, and eccentric to a great degree. His flights of oratory at times were truly sublime. He began his labors as the first regular installed minister, in 1834, in a little room, about twenty feet square, in the old barracks or stockades, which stood on the ground now occupied by the old frame residence of Joshua Wagenseller. . . .

“We will give one or two illustrations which, in themselves, will speak for the plain-tongued man of God, John T. Mitchell. One of his congregation, and a widow, who had but recently laid off her weeds, sold a cow and purchased what in those days was termed an elegant cloak, and she disposed of a brass preserving kettle and bought a bonnet (we presume a love of a one). This piece of wholesale extravagance had gone the rounds of the village, and loud were the censures for this wanton outlay, when to wear a bow or an artificial flower was equivilent (sic) to receiving sentence with the damned.

“Well, one Sunday morning when Father Mitchell was coming down on the pomps and vanities of the world, and earnestly hoping that none of his congregation would be guilty of putting on the flippery and flummery as worn by the worldings, just as his eloquence waxed warm on the subject of dress, in walked the widow with her new clothes, whereupon the sight of her was too much for him, and he said (pointing his finger directly at her,) ‘Yes, and there comes a woman with her cow upon her back and her brass kettle on her head.’ . . .

“In those days all the excitement the populace had, by way of breaking the monotony, was the landing of the steam-boats, and we are told that more always came on Sunday than any other day. Father Mitchell was exceedingly annoyed, from time to time, by many of his congregation jumping up and running to the river every time a boat whistled. Once, when the stampede began, Father Mitchell, with voice raised in tones of thunder, cried after them, ‘The wicked fleeth when no man pursueth.’ Whereupon a waggish fellow turned in the doorway, hat in hand, and, looking calmly at the divine, answered back, ‘and the righteous are as bold as a lion.’ . . .

“We think Father Mitchell must have been a firm believer in total depravity. There was a Universalist minister by the name of Carey, from Cincinnati (who was afterwards sent to Congress), came to Pekin and held a series of meetings in the two-story frame house directly opposite the old Foundry Church. This preacher, Carey, was brilliant and fluent of tongue, gathering about him, apparently, the whole village, to the disgust of Father Mitchell and his members. This was something new to them, it being the first time the broad-gauge religious track had struck Pekin, and many there were who were charmed with the doctrine. Still, some of the young men felt an innate sense of delicacy in openly and glaringly cutting old faithful Father Mitchell’s teachings, and they would walk about and reconnoitre until they would get to the corner of the building, and then stand and look around them for a few minutes, to see who was looking at them, and then like lightning dodge in. Father Mitchell, across the way, was of course taking in the full import of the scene, and feeling just a little bit of human chagrin at the boys leaving him for that glittering faith, he would walk up and down his church aisles, with his arms crossed behind his back, and as another and another would dodge in to hear Carey, he would say, very audibly, ‘there’s another one gone to hell.’”

Regarding Chapman’s comment on “total depravity,” it is unlikely that Rev. Mitchell, a Methodist, held to that doctrine. “Total depravity” is a Calvinist Protestant doctrine, whereas Methodism rejects Calvinism’s distinctive teachings on human salvation. Historically, however, Methodism has held to the orthodox Christian belief on the possibility of damnation, in opposition to the Universalist belief that all will be saved and no one will be finally damned – hence Mitchell’s displeasure with Carey’s preaching. (A biographical sketch of Rev. Mitchell was published in “Minutes of the Cincinnati Annual Conference of the Methodist Epicopal Church for the Year 1863,” pages 47-51.)

Chapman also provides an account of a memorable religious development in Pekin during the 1840s that the early settlers came to call the Sore-Throat Revival, when a frightening, deadly epidemic motivated many people to try to prepare their souls for Judgment Day, as these excerpts explain:

“The following persons composed the first choir: Samuel Rhoads, John W. Howard, James White, Daniel Creed, John M. Tinney, John Rhoads, and Henry Sweet, who acted as leader. This band of ‘ye singers’ met in Creed’s room for practice, and sometimes ‘took a hand,’ to pass the time until service. . . . This choir did valiant service in waiting on the sick during the fearful scourge and epidemic, called putrid sore throat, or black tongue, which swept over this part of the country during the winter of 1843 and 44. They paired off, night about, in watching the sick. But one evening Creed did not put in his appearance, and some of the boys suggested that he might be sick, and went to his room where they were wont to sing, but poor Daniel Creed had sung his last song on earth, and passed to the anthem choirs in the courts of Heaven, for they found him dead in his bed. The poor fellow had passed away in the loneliness of his own chamber, all alone, ‘to that bourne from whence no traveler returns.’ This fearful disease swept off, seemingly, half the village. The dead and the dying were in almost every house; men and women were aroused to a sudden sense of their obligations to their God, and with death apparently staring them in the face, they were crying out, ‘What shall we do to be saved?’ During this panic was started what was always afterwards termed the ‘sore-throat revival.’ Shops were shut, stores were closed, and all vocations for the time suspended, while the sick were nursed, the dead laid away, and the souls of the living presented to God for mercy. A pall hung over the infant town. A doom, at once dark, and deep, and solemn, seemed to settle over the citizens. Everybody joined the Church. Lucus Vanzant, the editor of the Pekin Gazette, . . . took sick early one night, and during the progress of the meeting, that same evening he sent his name down to the minister to be enrolled on the Church books. Vanzant got well.”