French colonists were the first Europeans to settle in the Illinois Country – including the future Tazewell and Peoria counties. The Illinois Country passed from French to British control in 1763, and then to American control in 1783. However, as we have seen in our review of the early history of our state, regardless of which national government claimed the lands of the future state of Illinois, they remained a sparsely populated area, inhabited chiefly by Native American tribes and relatively small groups of French colonists.

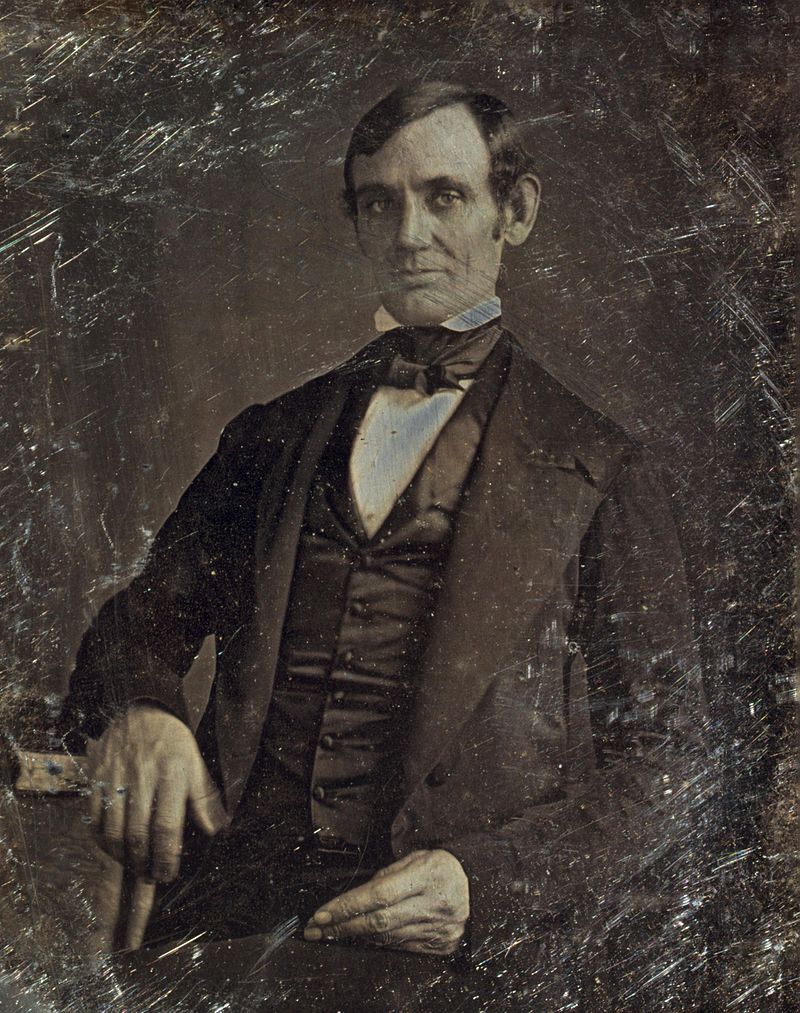

During the Revolutionary War, Britain’s attention was fixed upon its rebellious colonists in eastern North America, which gave George Rogers Clark of Virginia the opportunity he needed to capture the Illinois Country for his home state in 1778-1779 – with the help of Indian tribes and French colonists.

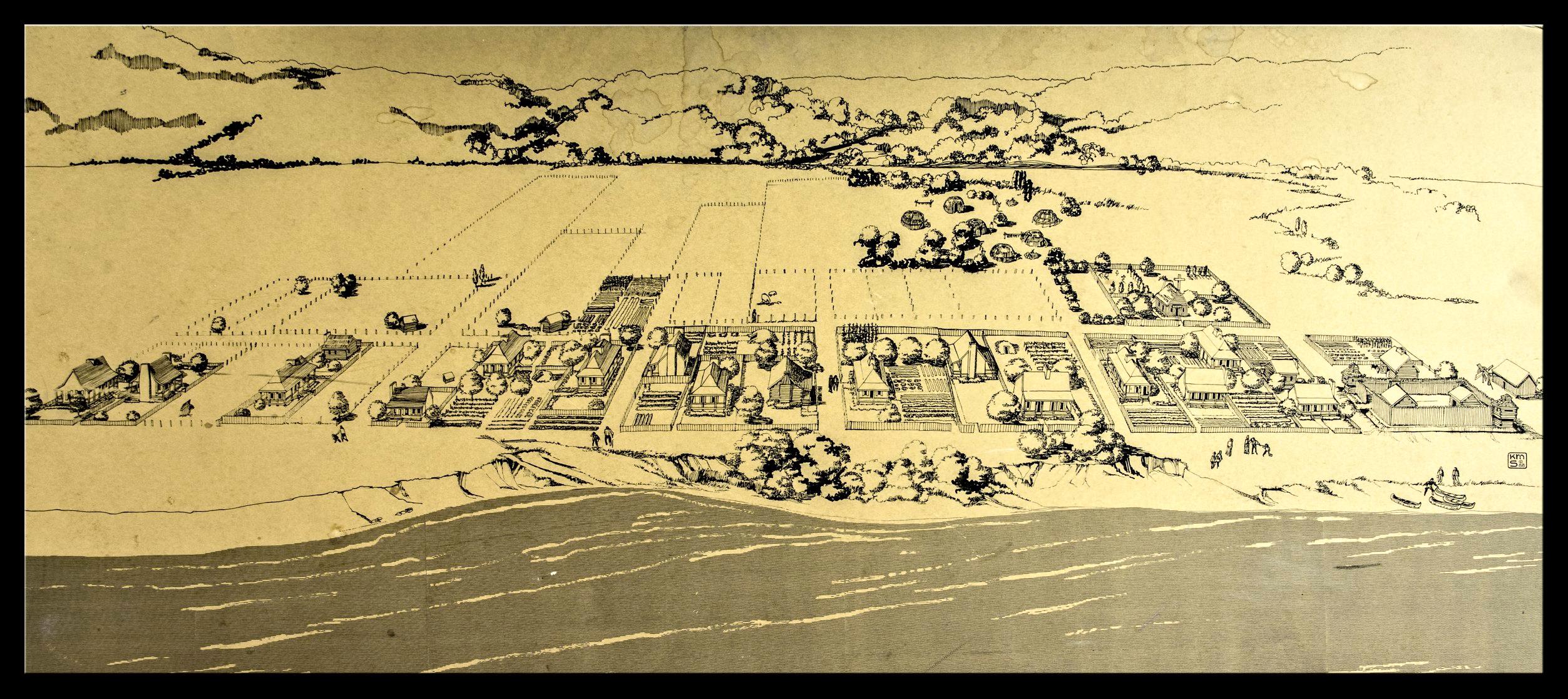

It was against the background of Clark’s Illinois Campaign that a group of French colonists and fur traders in 1778 established a village on the west shore of Peoria Lake – the area of the broadening of the Illinois River known to the native tribes as Pimiteoui. The village was located about where an Indian village had been in the days of Marquette and La Salle and afterwards. The site had also been the location of a French fort named Fort St. Louis du Pimiteoui, built by Henry Tonti in 1691, but a French presence was not continuous from Tonti’s day until Clark’s Illinois Campaign. The village of 1778 was the predecessor of the present city of Peoria.

Charles C. Chapman’s 1879 “History of Tazewell County,” page 193, briefly tells the story of this village in these words:

“The next attempt to settle this section of Illinois [after La Salle’s expedition] was made at the upper end of Peoria lake in 1778. The country in the vicinity of this lake was called by the Indians Pim-i-te-wi, that is, a place where there are many fat beasts. Here the town of Laville de Meillet, named after its founder, was started. Within the next twenty years, however, the town was moved down to the lower end of the lake to the present site of Peoria. In 1812 the town was destroyed and the inhabitants carried away by Captain Craig. In 1813 Fort Clark was erected there by Illinois troops engaged in the war of 1812. Five years later it was destroyed by fire.”

The French predecessor of the city of Peoria is more accurately spelled “La Ville de Maillet,” meaning “Maillet’s village.” According to Peoria Historical Society records, the town’s founder was a French trader named Robert Maillet, who built a cabin for himself and his family near the outlet of Peoria Lake in 1761. The small village that grew up around Maillet’s cabin moved upriver to the future site of Peoria in 1778, growing to become a town and flourishing as a trading link between Canada and the French settlements on the Mississippi until the War of 1812. During that war, the town was destroyed in an attack that American militia forces of the Illinois Territory launched against the Indian tribes around Peoria Lake. Although the townsfolk were U.S. citizens, they were taken prisoner and carried off to southern Illinois – but a few returned after the War of 1812.

Nehemiah Matson’s 1882 book “Pioneers of Illinois” includes the following eyewitness descriptions of La Ville de Maillet:

“In 1820 Hypolite Maillet, in his sworn testimony before Edward Cole, register of title land-office at Edwardsville, in relation to French claims, said that he was forty-five years old, and born in a stockade fort which stood near the southern extremity of Peoria Lake. In the winter of 1788 a party of Indians came to Peoria to trade, and, in accordance with their former practice, took quarters in the fort, but getting on a drunken spree they burned it down. In the spring of 1819, [when] Americans commenced a settlement here at Peoria, the outlines of the old French fort were plain to be seen on the high ground near the lake, and a short distance above the present site of the Chicago and Rock Island depot. . . .

“According to the statements of Antoine Des Champs, Thomas Forsyth, and others, who had long been residents of Peoria previous to its destruction in 1812, we infer that the town contained a large population . . . The town was built along the beach of the lake, and to each house was attached an outlet for a garden, which extended back on the prairie.

“The houses were all constructed of wood, one story high, with porches on two sides, and located in a garden surrounded with fruit and flowers. Some of the dwellings were built of hewed timbers set upright, and the space between the posts filled in with stone and mortar, while others were built of hewed logs notched together after the style of a pioneer’s cabin. The floors were laid with puncheons, and the chimney built with mud and sticks. When Colonel Clark took possession of Illinois in 1778 he sent three soldiers, accompanied by two Frenchmen, in a canoe to Peoria to notify the people that they were no longer under British rule but citizens of the United States.

“Among these soldiers was a man named Nicholas Smith, a resident of Bourbon county, Kentucky, and whose son, Joseph Smith (Dod Joe), was among the first American settlers of Peoria . . . Mr. Smith said Peoria at the time of his visit was a large town, built along the beach of the lake, with narrow, unpaved streets, and houses constructed of wood. Back of the town were gardens, stock-yards, barns, etc., and among these was a wine-press, with a large cellar or under-ground vault for storing wine. There was a church with a large wooden cross raised above the roof, and with gilt lettering over the door. There was an unoccupied fort on the bank of the lake, and close by it a wind-mill for grinding grain. The town contained six stores or places of trade, all of which were well filled with goods for the Indian market.”

The destruction of La Ville de Maillet was not the end of early French settlement in our area, for several of the French former inhabitants of La Ville de Maillet returned to Peoria Lake after the war, setting up a trading post and small settlement near the Illinois River in what was to become Tazewell County.

Next week we will review the story of that French trading post.