The British had possession of the Illinois Country for a mere 12 years when the unrest began in the Thirteen Colonies that soon would break out into the American War of Independence – the Revolutionary War – which would last for eight years, ending with Britain’s recognition of the independence of the United States of America in 1783.

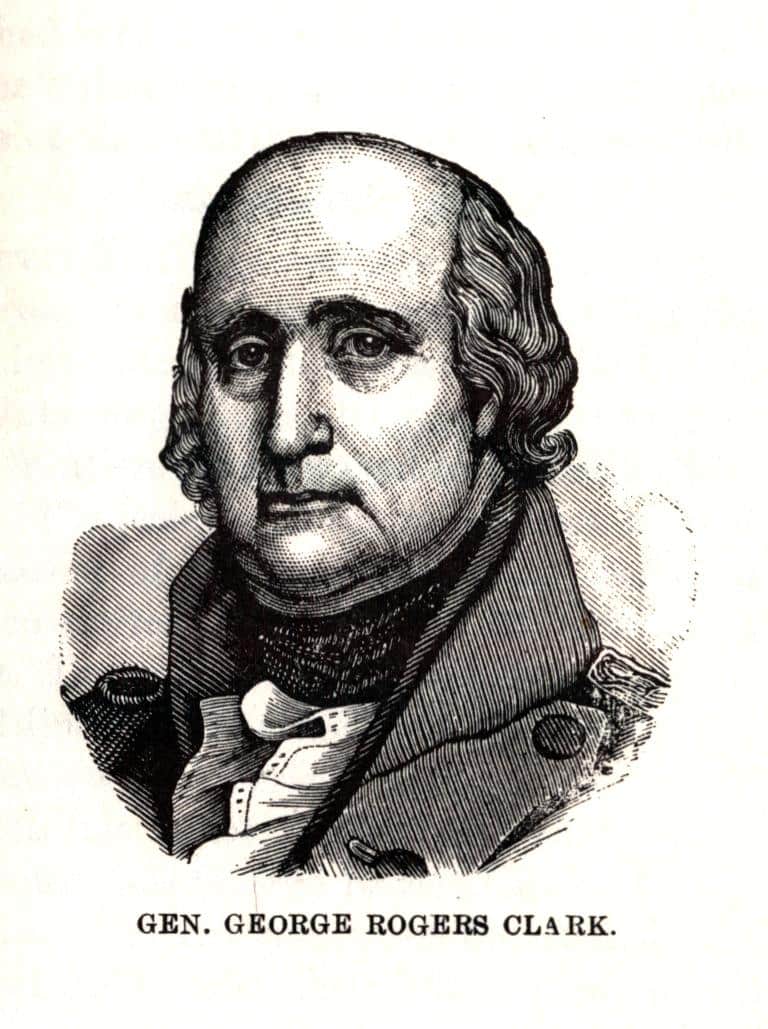

Naturally, most of the action in the war took place within the 13 colonies that had declared themselves to be independent states. In the years 1778 and 1779, however, an officer in the militia of the Commonwealth of Virginia, Lt. Col. George Rogers Clark (1752-1818), led a small and swift military force which executed a daring campaign that wrested control of the Illinois Country from Britain. As we saw previously, Britain’s hold on the sparsely-populated Illinois Country was then still rather tenuous, and neither the Indians nor the French settlers living there nurtured strong ties of loyalty to Britain.

Clark himself almost lived long enough to see Illinois statehood, and it is thanks to Clark and his men that Illinois and its neighboring states are parts of the United States of America today. (Clark County in southeastern Illinois, on the Indiana border, established in 1819, is named in honor of George Rogers Clark.) However, it shouldn’t be forgotten that Clark was fighting as much for his home state of Virginia as he was for the newly-minted confederacy of upstart English colonies that were claiming the dignity of sovereign states – states that each had hopes and plans for their own westward expansion in the Indian Reserve.

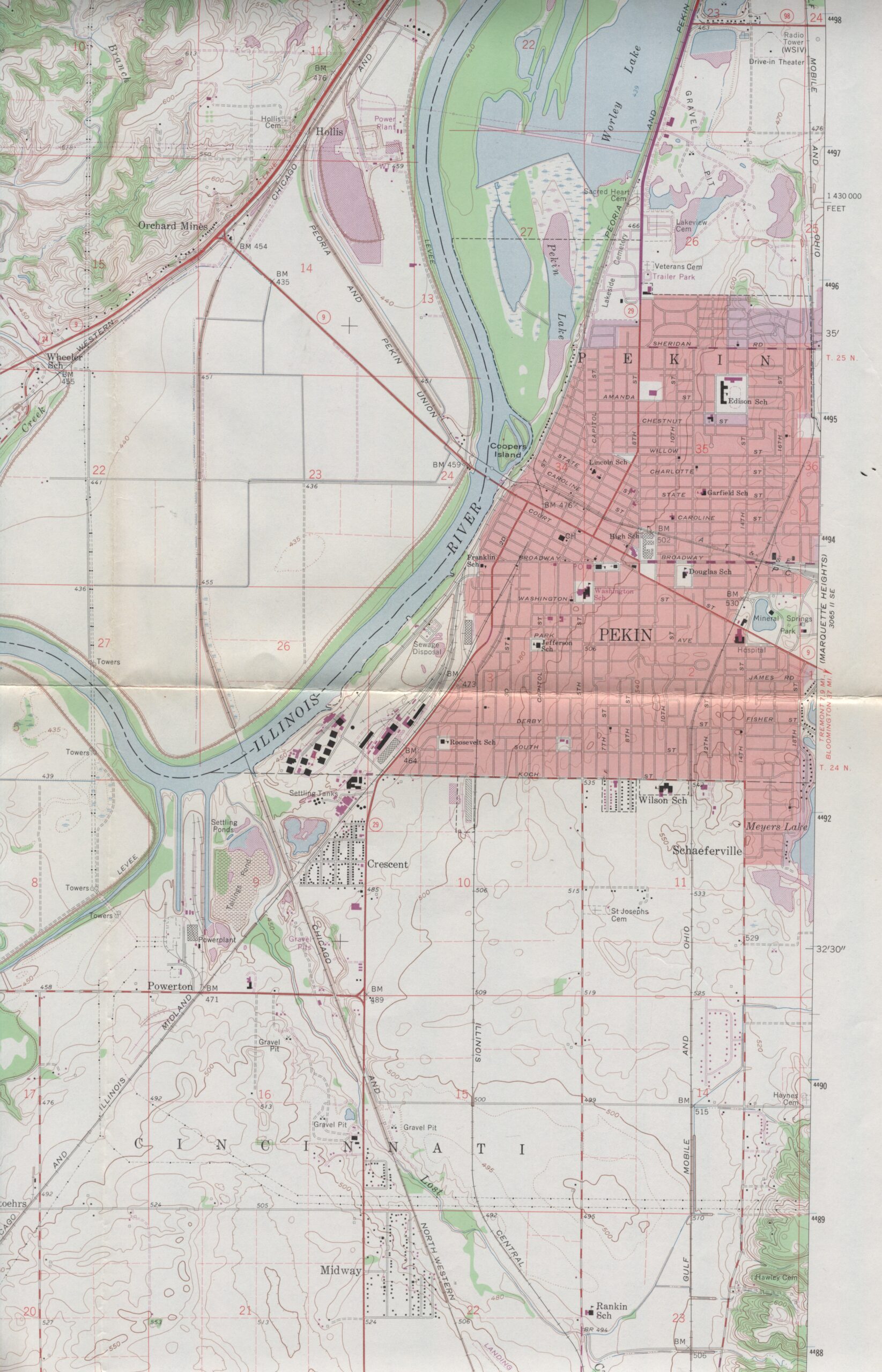

Consequently, when Clark completed the conquest of the Illinois Country, he immediately organized it as a new – and immensely vast – county of the Commonwealth of Virginia: Illinois County, which included not only Illinois but also Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin, with the county seat at Kaskaskia, an arrangement that, as we shall see next time, was to last a mere five years.

The story of Clark’s Illinois Campaign was told in Charles C. Chapman’s 1879 “History of Tazewell County,” pages 51-55, in these words:

“The hero of the achievements by which this beautiful land was snatched as a gem from the British Crown, was George Rogers Clark, of Virginia. He had closely watched the movements of the British throughout the Northwest, and understood their whole plan; he also knew the Indians were not unanimously in accord with the English, and therefore was convinced that if the British could be defeated and expelled from the Northwest, the natives might be easily awed into neutrality. Having convinced himself that the enterprise against the Illinois settlement might easily succeed, he repaired to the capital of Virginia, arriving Nov. 5, 1777. While he was on his way, fortunately, Burgoyne was defeated (Oct. 17), and the spirits of the colonists were thereby greatly encouraged. Patrick Henry was Governor of Virginia, and at once entered heartily into Clark’s plans. After satisfying the Virginia leaders of the feasibility of his project, he received two sets of instructions, — one secret, the other open. The latter authorized him to enlist seven companies to go to Kentucky, and serve three months after their arrival in the West. The secret order authorized him to arm these troops, to procure his powder and lead of General Hand at Pittsburg, and to proceed at once to subjugate the country.

“With these instructions Col. Clark repaired to Pittsburg, choosing rather to raise his men west of the mountains, as he well knew all were needed in the colonies in the conflict there. He sent Col. W. B. Smith to Holstein and Captains Helm and Bowman to other localities to enlist men; but none of them succeeded in raising the required number. The settlers in these parts were afraid to leave their own firesides exposed to a vigilant foe, and but few could be induced to join the expedition. With these companies and several private volunteers Clark commenced his descent of the Ohio, which he navigated as far as the falls, where he took possession of and fortified Corn Island, a small island between the present cities of Louisville, Ky., and New Albany, Ind. Here, after having completed his arrangements and announced to the men their real destination, he left a small garrison; and on the 24th of June, during a total eclipse of the sun, which to them augured no good, they floated down the river. His plan was to go by water as far as Fort Massac, and thence march direct to Kaskaskia. Here he intended to surprise the garrison, and after its capture go to Cahokia, then to Vincennes, and lastly to Detroit. Should he fail, he intended to march directly to the Mississippi river and cross it into the Spanish country. Before his start he received good items of information: one, that an alliance had been formed between France and the United States, and the other, that the Indians throughout the Illinois country and the inhabitants at the various frontier posts had been led by the British to believe that the ‘Long Knives,’ or Virginians, were the most fierce, bloodthirsty and cruel savages that ever scalped a foe. With this impression on their minds, Clark saw that proper management would cause them to submit at once from fear, if surprised, and then from gratitude would become friendly, if treated with unexpected lenity. The march to Kaskaskia was made through a hot July sun, they arriving on the evening of the 4th of July, 1778. They captured the fort near the village and soon after the village itself, by surprise, and without the loss of a single man and without killing any of the enemy. After sufficiently working on the fears of the natives, Clark told them they were at perfect liberty to worship as they pleased, and to take whichever side of the great conflict they would; also he would protect them against any barbarity from British or Indian foe. This had the desired effect; and the inhabitants, so unexpectedly and so gratefully surprised by the unlooked-for turn of affairs, at once swore allegiance to the American arms; and when Clark desired to go to Cahokia on the 6th of July, they accompanied him, and through their influence the inhabitants of the place surrendered and gladly placed themselves under his protection.

“In the person of M[onsignor] Gibault, priest of Kaskaskia, Clark found a powerful ally and generous friend. Clark saw that, to retain possession of the Northwest and treat successfully with the Indians, he must establish a government for the colonies he had taken. St. Vincent, the post next in importance to Detroit, remained yet to be taken before the Mississippi valley was conquered. M. Gibault told him that he would alone, by persuasion, lead Vincennes to throw off its connection with England. Clark gladly accepted this offer, and July 14th, in company with a fellow-townsman, Gibault started on his mission of peace. On the 1st of August he returned with the cheerful intelligence that everything was peaceably adjusted at Vincennes in favor of the Americans. During the interval, Col. Clark established his courts, placed garrisons at Kaskaskia and Cahokia, successfully re-enlisted his men, and sent word to have a fort (which proved the germ of Louisville) erected at the falls of the Ohio.

“While the American commander was thus negotiating with the Indians, [Col. Henry] Hamilton, the British Governor of Detroit, heard of Clark’s invasion, and was greatly incensed because the country which he had in charge should be wrested from him by a few ragged militia. He therefore hurriedly collected a force, marched by way of the Wabash, and appeared before the fort at Vincennes. The inhabitants made an effort to defend the town, and when Hamilton’s forces arrived Captain Helm and a man named Henry were the only Americans in the fort. These men had been sent by Clark. The latter charged a cannon and placed it in the open gateway, and the Captain stood by it with a lighted match and cried out, as Hamilton came in hailing distance, ‘Halt!’ The British officer, not knowing the strength of the garrison, stopped, and demanded the surrender of the fort. Helm exclaimed, ‘No man shall enter here till I know the terms.’ Hamilton responded, ‘You shall have the honors of war.’ The entire garrison consisted of one officer and one private.

“On taking Kaskaskia, Clark made a prisoner of Rocheblave, commander of the place, and got possession of all his written instructions for the conduct of the war. From these papers he received important information respecting the plans of Col. Hamilton, Governor at Detroit, who was intending to make a vigorous and concerted attack upon the frontier. After arriving at Vincennes, however, he gave up his intended campaign for the winter, and trusting to his distance from danger and to the difficulty of approaching him, sent off his Indian warriors to prevent troops from coming down the Ohio, and to annoy the Americans in all ways. Thus he sat quietly down to pass the winter with only about eighty soldiers, but secure, as he thought, from molestation. But he evidently did not realize the character of the men with whom he was contending. Clark, although he could muster only one hundred and thirty men, determined to take advantage of Hamilton’s weakness and security, and attack him as the only means of saving himself; for unless he captured Hamilton, Hamilton would capture him. Accordingly, about the beginning of February, 1779, he dispatched a small galley which he had fitted out, mounted with two four-pounders and four swivels and manned with a company of soldiers, and carrying stores for his men, with orders to force her way up the Wabash, to take her station a few miles below Vincennes, and to allow no person to pass her. He himself marched with his little band, and spent sixteen days in traversing the country from Kaskaskia to Vincennes, passing with incredible fatigue through woods and marshes. He was five days in crossing the bottom lands of the Wabash; and for five miles was frequently up to the breast in water. After overcoming difficulties which had been thought insurmountable, he appeared before the place and completely surprised it. The inhabitants readily submitted, but Hamilton at first defended himself in the fort. Next day, however, he surrendered himself and his garrison prisoners-of-war. By his activity in encouraging the hostilities of the Indians and by the revolting enormities perpetrated by those savages, Hamilton had rendered himself so obnoxious that he was thrown in prison and put in irons. During his command of the British frontier posts he offered prizes to the Indians for all the scalps of the Americans they would bring him, and earned in consequence thereof the title, ‘Hair-Buyer General,’ by which he was ever afterward known.

“The services of Clark proved of essential advantage to his countrymen. They disconcerted the plans of Hamilton, and not only saved the western frontier from depredations by the savages, but also greatly cooled the ardor of the Indians for carrying on a contest in which they were not likely to be the gainers. Had it not been for this small army, a union of all the tribes from Maine to Georgia against the colonies might have been effected, and the whole current of our history changed.

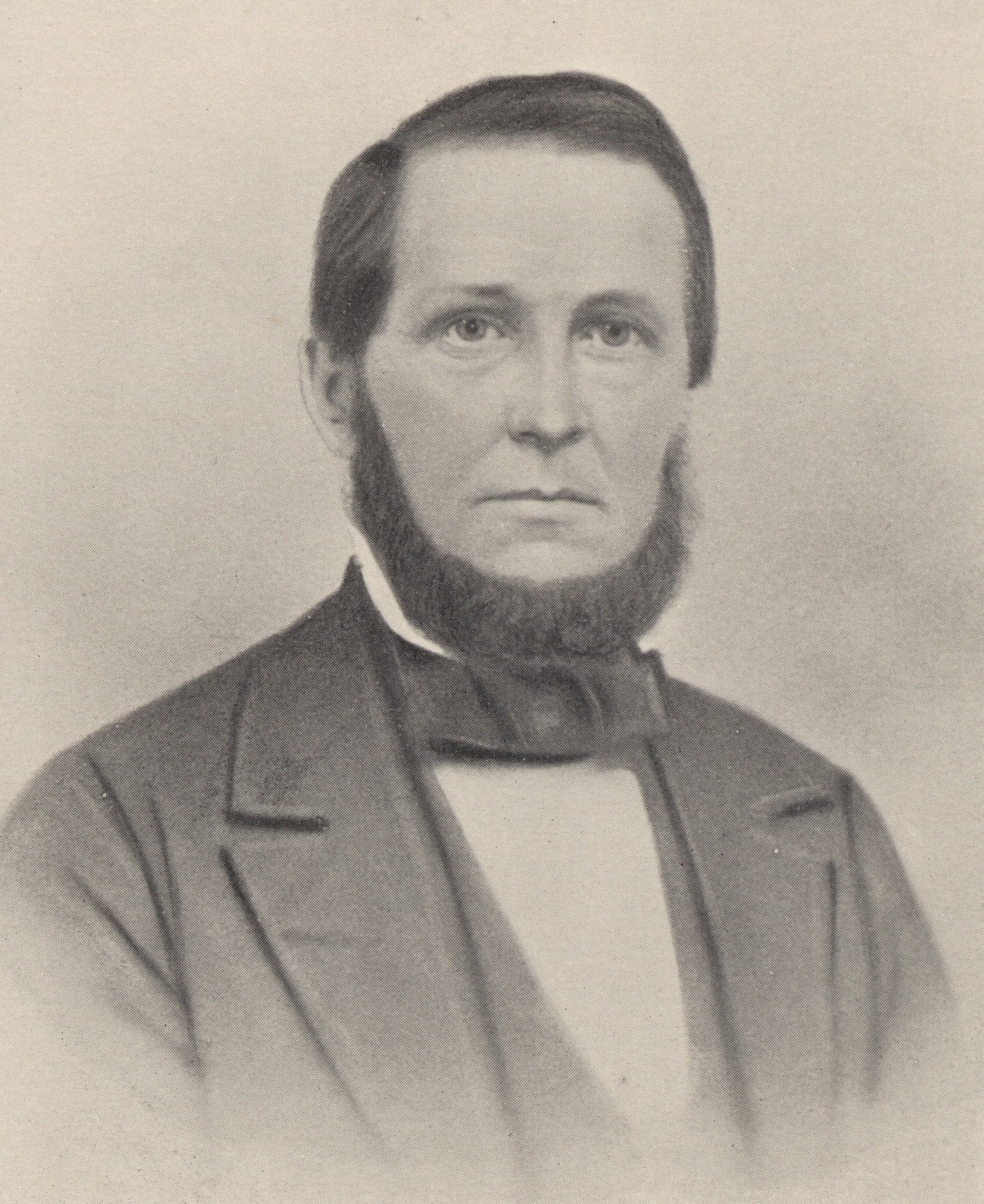

“In October, 1778, after the successful campaign of Col. Clark, the assembly of Virginia erected the conquered country, embracing all the territory northwest of the Ohio river, into the County of Illinois, which was doubtless the largest county in the world, exceeding in its dimensions the whole of Great Britain and Ireland. To speak more definitely, it contained the territory now embraced in the great States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan. On the 12th of December, 1778, John Todd was appointed Lieutenant-Commandant of this county by Patrick Henry, then Governor of Virginia, and accordingly, also, the first of Illinois County.”